As always, dear readers, welcome.

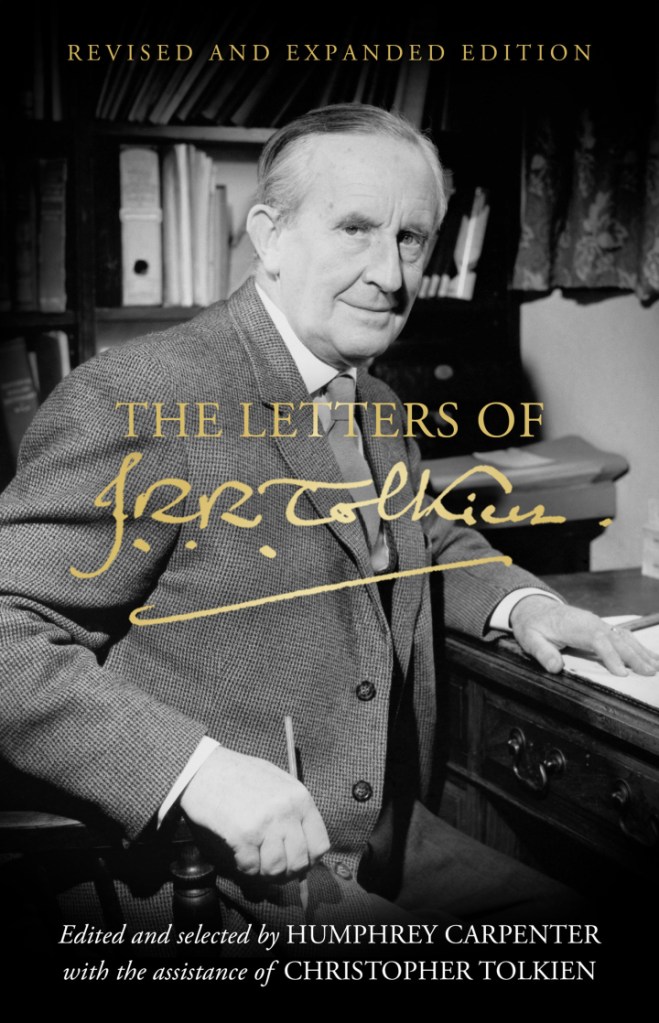

We know that Tolkien had mixed feelings about allegory. As he wrote in a long, detailed description of his work to Milton Waldman in 1951:

“I dislike Allegory—the conscious and intentional allegory—yet any attempt to explain the purport of myth or fairytale must use allegorical language. (And, of course, the more ‘life’ a story has the more readily will it be susceptible of allegorical interpretations: while the better a deliberate allegory is made the more nearly will it be acceptable just as a story.)” (from the typescript of a letter to Milton Waldman, late in 1951, Letters, 204)

This has made me think about Saruman and the Shire.

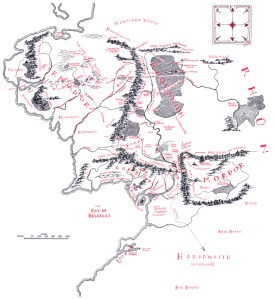

Defeated at the end of the Second Age, it’s easy to see from a map why Sauron returned to Mordor as his refuge.

It’s clearly a natural fortress, protected on three sides by forbidding mountain ranges pierced by only two gates, the Morannon

(the Hildebrandts)

and Minas Morgul (formerly Minas Ithil).

(another Hildebrandts)

His command center, the Barad-dur, was located there.

(and yet another Hildebrandts)

Sited near an active volcano, Mt. Doom,

(This is actually Villarrica in Chile erupting in March, 2015.)

it was also a blighted land, nearly waterless and bleak.

(This is the Parque Nacional de Timanfaya on the island of Lanzarote in the Canary Islands. As someone who loves the US Southwest, I find this place absolutely stunning, but, imagining it marched across by companies of orcs and suffered across by Sam and Frodo, it might easily stand in for Mordor.)

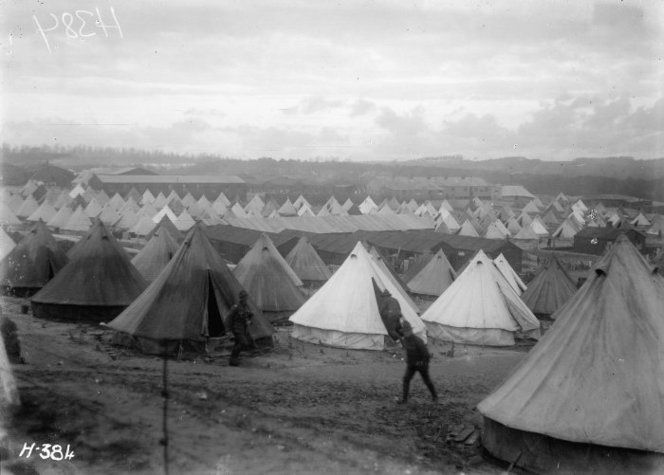

Although at the time of The Lord of the Rings it has become a vast camp,

filled with all of the tents and workshops and stables which an army like Sauron’s would require, I have no sense that it was ever anything more than as it must have looked even in the Second Age: bleak and waterless and dominated to the north by Mt Doom, a vast volcanic plain. Sauron hadn’t intended to blight it. Nature had already made it that way and it was useful for what he required: protection from prying eyes and invading troops and space to spread his growing forces. (Although I wonder about his water supply—Sam and Frodo are lucky to find the trickle they do—and even “dark pools fed by threads of water trickling down from some source higher up the valley”—by the western mountain wall—The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 2, “The Land of Shadow”. Food seems to have been supplied by slave farms to the south and southeast, also briefly described in this chapter. Ever-practical Sam wonders about all of this: “ ‘Pretty hopeless, I call it—saving that where there’s such a lot of folk there must be wells or water, not to mention food.’ “ )

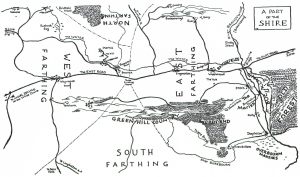

In contrast, there was the Shire—

(JRRT)

As Tolkien imagined it:

“The Shire is placed in a water and mountain situation and a distance from the sea and a latitude that would give it a natural fertility, quite apart from the stated fact that it was a well-tended region when they [the hobbits] took it over…” (letter to Naomi Mitchison, 25 September, 1954, Letters, 292)

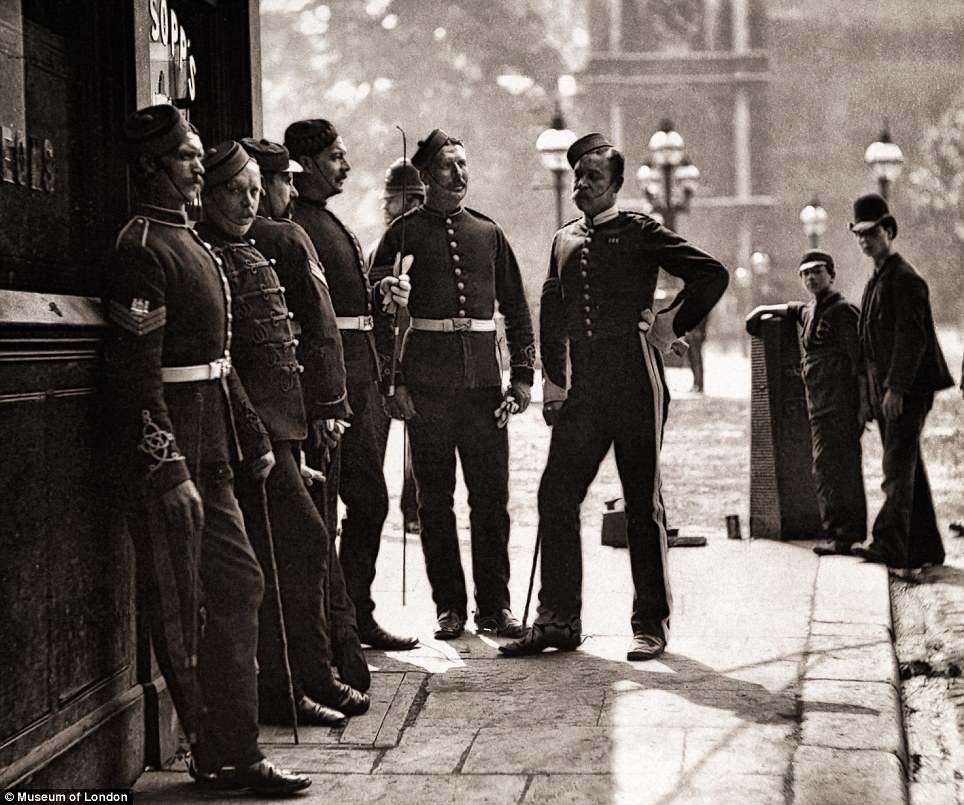

It was based, as he stated more than once, on

“…a Warwickshire village of about the period of the Diamond Jubilee [the 60th anniversary of Queen Victoria’s ascension to the throne, 1897]…” (letter to Allen & Unwin, 12 December, 1955, Letters, 334)

which, although the actual village, Sarehole, was just south of the booming manufacturing center of Birmingham, Tolkien describes this world as “…in a pre-mechanical age.” (letter to Deborah Webster, 25 October, 1958, Letters, 411)

And, to Tolkien, this was

“…in the quiet of the world, when there was less noise and more green…” (The Hobbit, Chapter One, “An Unexpected Party”)

But then Saruman arrives, telling the hobbits:

“ ‘One ill turn deserves another…It would have been a sharper lesson, if only you had given me a little more time and more Men. Still I have already done much that you will find it hard to mend or undo in your lives. And it will be pleasant to think of that and set it against my injuries.’ ” (The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 8, “The Scouring of the Shire”)

It’s clear from the description given us in “The Scouring of the Shire”, however, that what Saruman intends isn’t just wanton destruction, but something more complex: a complete reorganization of the Shire. Part of that is a social restructuring, where a form of communism is forced upon the population. Monitoring that is the apparatus of a police state, with many rules, a curfew, and a number of the hobbits themselves being recruited to the “Shirriffs”. But there’s more:

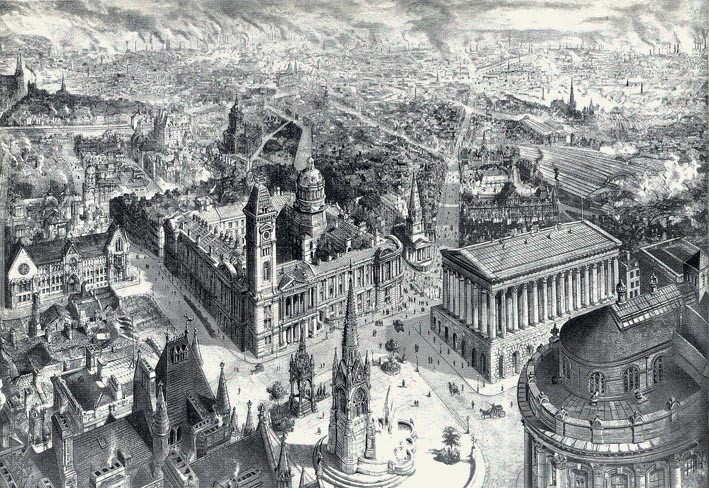

“The pleasant row of old hobbit-holes in the bank on the north side of the Pool were deserted, and their little gardens that used to run down bright to the water’s edge were rank with weeds. Worse, there was a whole line of the ugly new houses all along Pool Side, where the Hobbiton Road ran close to the bank. An avenue of trees had stood there. They were all gone. And looking with dismay up the road towards Bag End they saw a tall chimney of brick in the distance. It was pouring out black smoke into the evening air.”

Thus, what Saruman was clearly intending wasn’t just desolation, like Mordor, but rather something more like the imaginary Coketown of Charles Dickens’ Hard Times, 1854:

“It was a town of red brick, or of brick that would have been red if the smoke and ashes had allowed it; town of machinery and tall chimneys, out of which interminable serpents of smoke trailed themselves for ever and ever, and never got uncoiled. It had a black canal in it, and a river that ran purple with ill-smelling dye, and vast piles of building full of windows where there was a rattling and a trembling all day long, and where the piston of the steam-engine worked monotonously up and down, like the head of an elephant in a state of melancholy madness. It contained several large streets all very like one another, and many small streets still more like one another, inhabited by people equally like one another, who all went in and out at the same hours, with the same sound upon the same pavements, to do the same work, and to whom every day was the same as yesterday and to-morrow, and every year the counterpart of the last and the next.” (Hard Times, Chapter 5, “The Keynote” which you can read here: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/786/786-h/786-h.htm )

Tolkien more than once lamented the passing of the “quiet of the world” and his Shire, which he described in a letter as “where an ordered, civilized, if simple and rural life is maintained” embodied for him that quiet. (from that same letter to Milton Waldman, late 1951, Letters, 219)

And so, although JRRT wrote, in a letter to the editor of New Republic, Michael Straight, that:

“There is no special reference to England in the ‘Shire’…there is no post-war reference.”

at the same time, he adds:

“…the spirit of ‘Isengard’, if not of Mordor, is of course always cropping up.” (draft of a letter to Michael Straight, “probably January or February 1956, Letters, 340)

We know what that spirit is inspired by, as Treebeard tells us:

“He has a mind of metal and wheels; and he does not care for growing things, except as far as they serve him for the moment.” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 4, “Treebeard”)

Isengardism—or Sarumanism (a word JRRT himself employs in that same letter to Naomi Mitchison quoted above, saying that he is not a ‘reformer’ (by exercise of power) since it seems doomed to Sarumanism”) to Tolkien meant brutal change—in this case, in the conversion of the Shire into a mini-industrial state, run by a Stalinist tyrant and a cowed population. Considering Tolkien’s sadness at the conversion of the rural world of his childhood into the industrial world of his present, might we not then see what Saruman does to the Shire as rather like allegory as Tolkien once defined it:

“Of course, Allegory and Story converge, meeting somewhere in Truth.”? (letter to Sir Stanley Unwin, 31 July, 1947, Letters, 174)

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

Think green thoughts,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O