Tags

books, Fantasy, Gorbag, Grishnakh, lotr, Orcs, Saruman, Sauron, sergeant, sergeants, Shagrat, soldiers, speech, The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien, Ugluk

As always, welcome, dear readers.

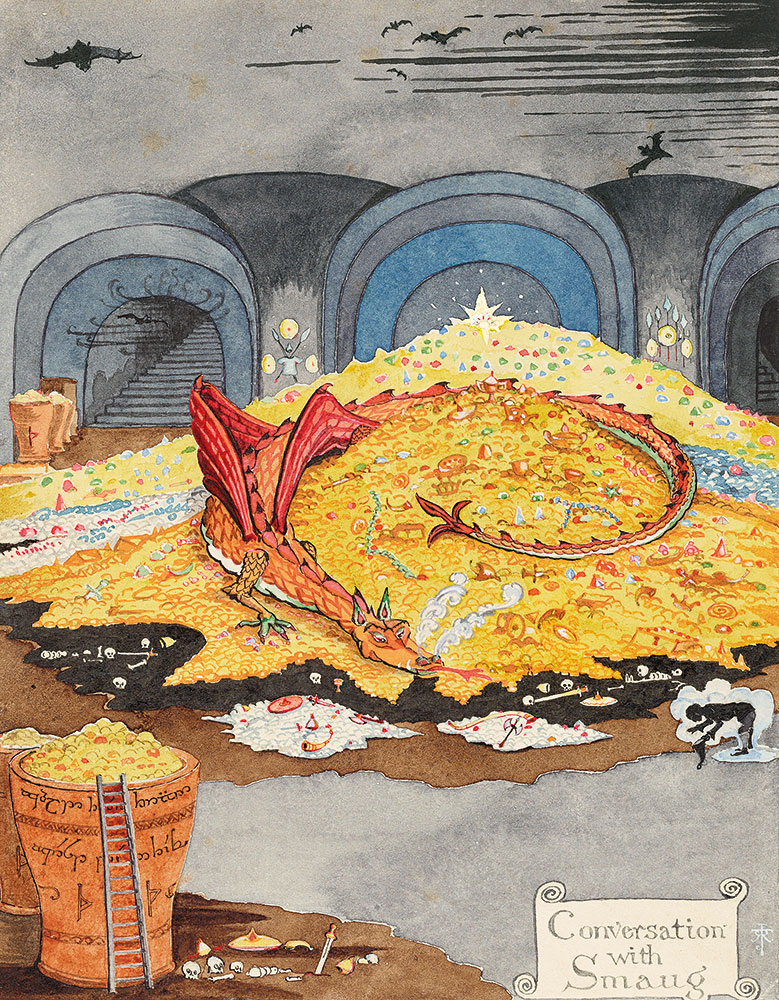

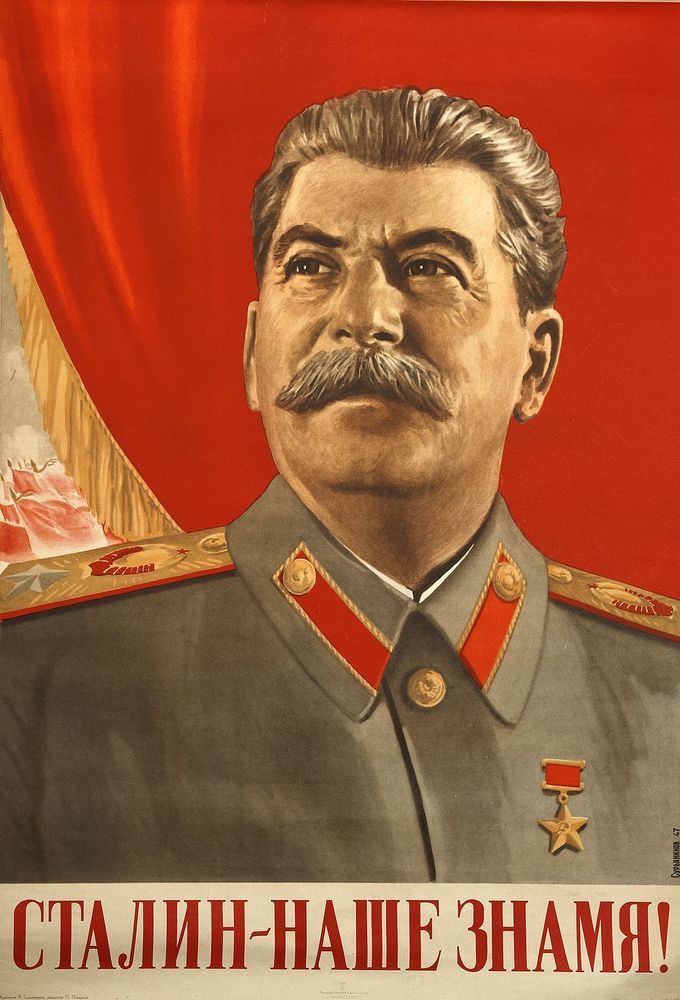

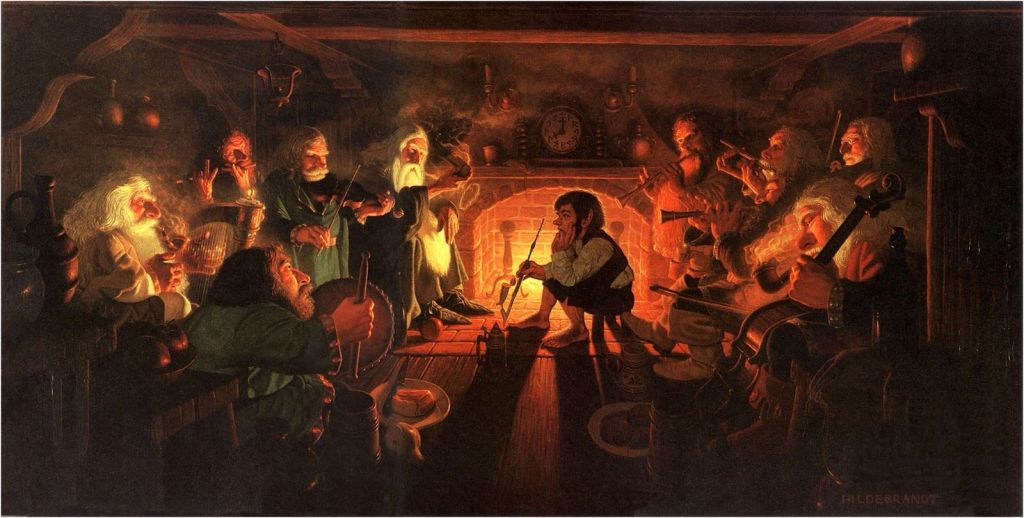

In Parts 1 and 2 of this short series, I’ve looked at Tolkien’s use of speech to characterize—and bring to life—the antagonists of The Lord of the Rings, leaving out Sauron, as having little to say for himself, but observing Saruman,

(the Hildebrandts)

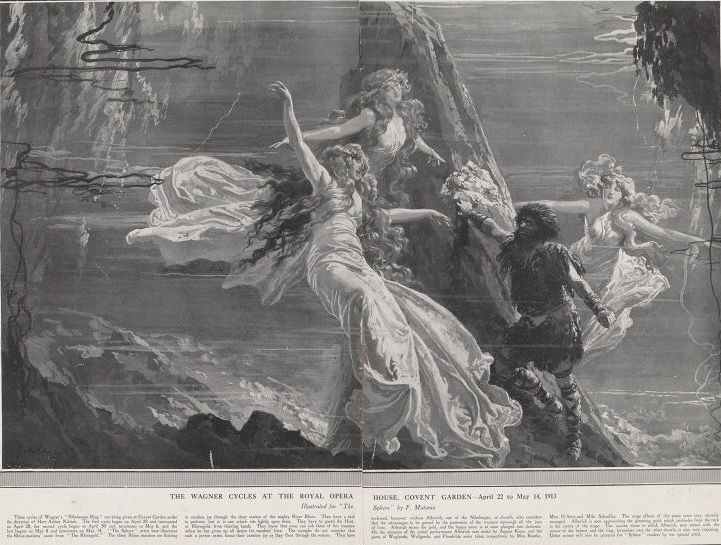

the chief of the Nazgul,

(the Hildebrandts)

and the Mouth of Sauron.

(Douglas Beekman)

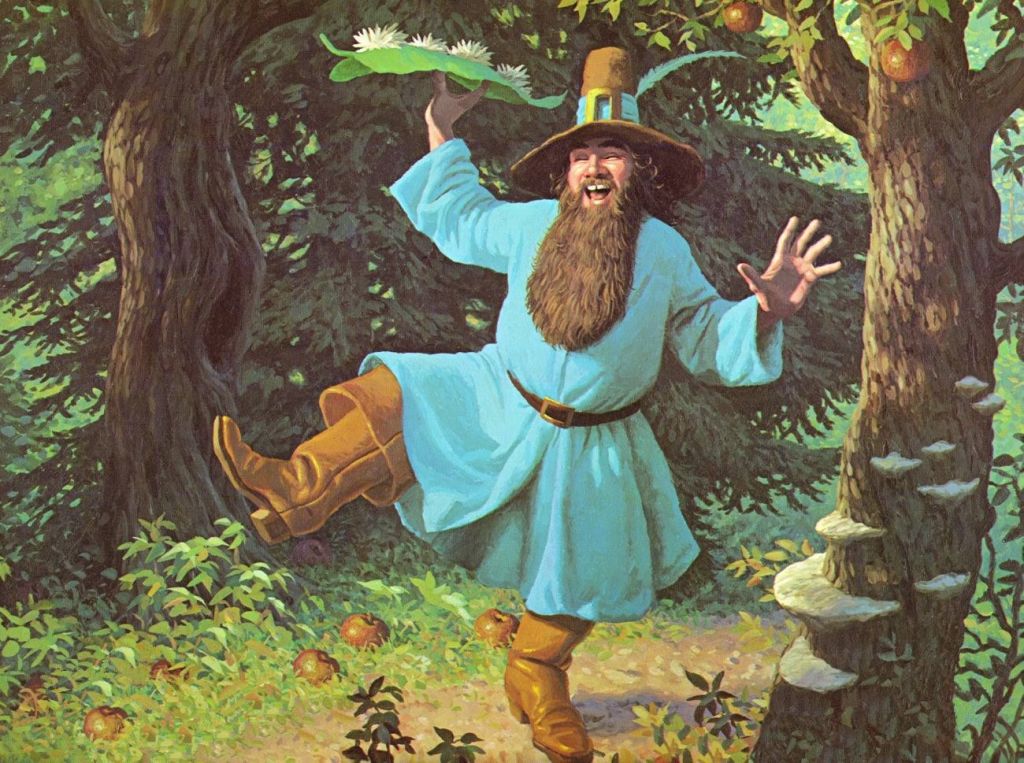

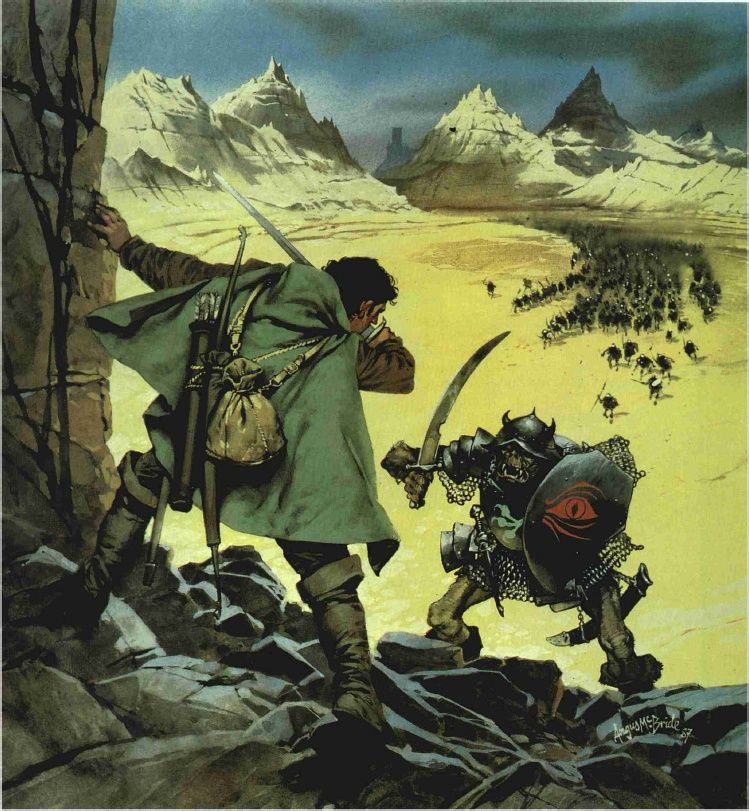

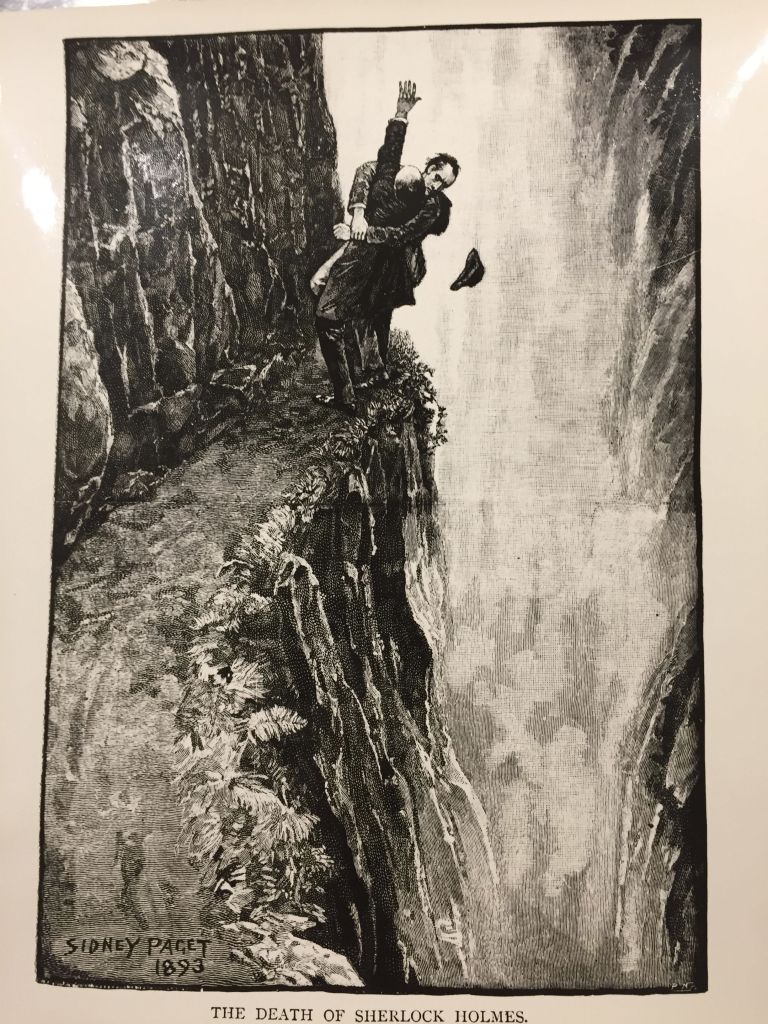

I’ve been doing this as a descent down the social ladder and now we’ve reached the foot with the Orcs.

(Alan Lee)

JRRT had very complex thoughts and feelings about them, as his letters show us (see, for instance, some of his thoughts in his unfinished, unsent letter to Peter Hastings, September, 1954, Letters, 285 and 291) but then the Orcs themselves seem more complex than mere (in more modern terms) “cannon-fodder”—that is, a simple mass of undifferentiated infantry.

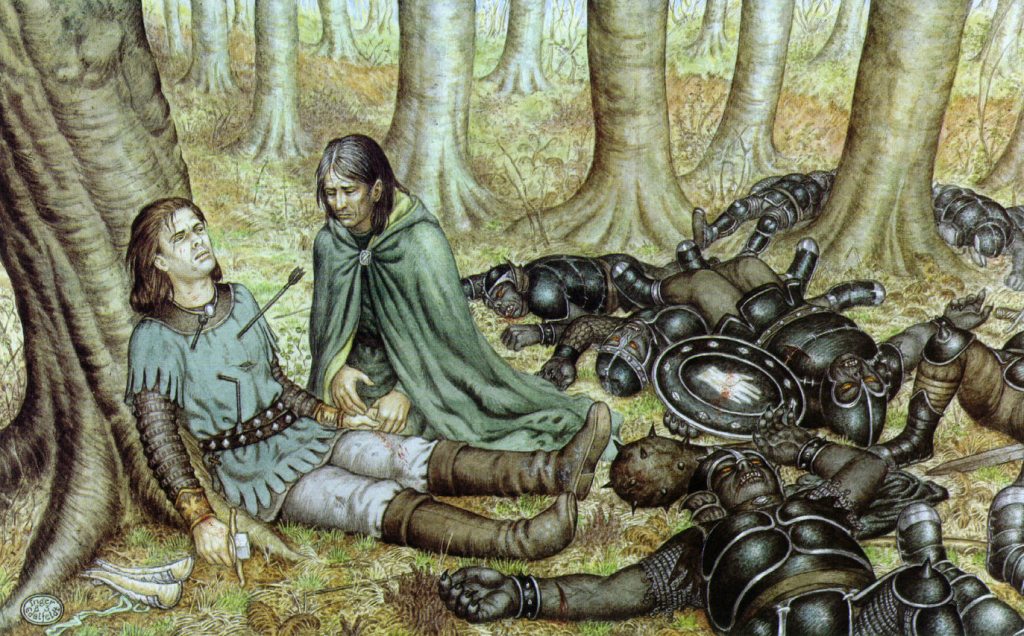

(Alan Lee)

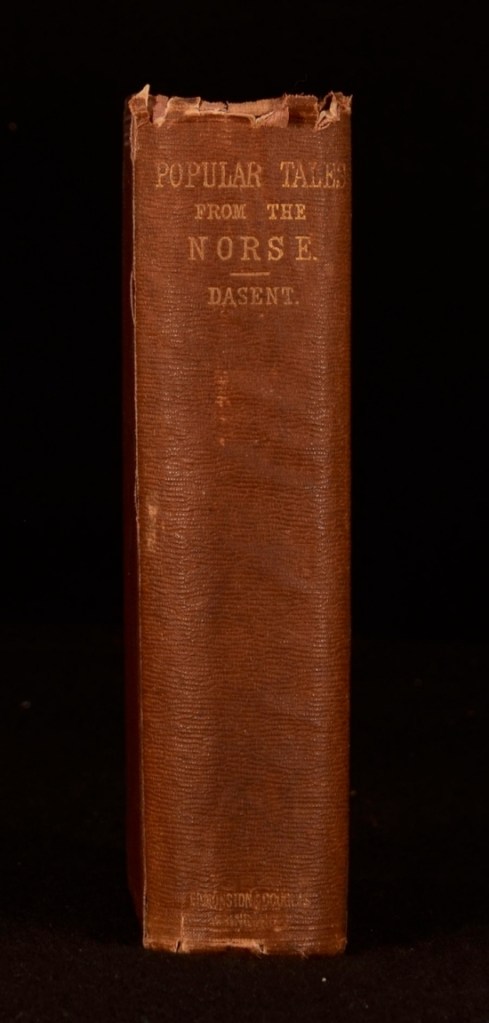

Something which has always struck me about them is Tolkien’s choices for their speech. At one level, as I pointed out in “Tolkien Among the Indians”, (21 January, 2026), one of their leaders, Ugluk, can sound like a figure out of James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans—

“ ‘We are the fighting Uruk-hai! We slew the great warrior. We took the prisoners. We are the servants of Saruman the Wise, the White Hand: the Hand that gives us man’s-flesh to eat. We came out of Isengard, and led you here, and we shall lead you back by the way we choose. I am Ugluk. I have spoken.’ ”

On another level—but here I want to quote another of Tolkien’s letters, one often cited when referring to Sam Gamgee:

“My ‘Sam Gamgee’ is indeed, as you say, a reflexion of the English Soldier, of the privates and batmen [officers’ servants, not denizens of Gotham] I knew in the 1914 war, and recognized as so far superior to myself.” (draft of a letter to H. Cotton Minchin, April, 1956, Letters, 358)

and obviously Tolkien knew what he intended, but I’ve always seen those “privates and batmen” as something more: as models for the Orcs—

and their commanders, Ugluk and Grishnakh—and later Shagrat and Gorbag—not as of the officer class, to which Tolkien belonged—

but as sergeants, the tough, experienced men who ran the infantry on a day-to-day basis.

Here they are, talking—

“ ‘Orders,’ said a third voice in a deep growl. ‘Kill all but NOT the Halflings; they are to be brought back ALIVE as quickly as possible. That’s my orders.’

“ ‘What are they wanted for?’ asked several voices. ‘Why alive? Do they give good sport?’

‘No! I heard that one of them has got something, something that’s wanted for the War, some Elvish plot or other. Anyway they’ll both be questioned.’

‘Is that all you know? Why don’t we search them and find out? We might find something that we could use ourselves.’

‘That is a very interesting remark,’ sneered a voice, softer than the others but more evil. ‘I may have to report that. The prisoners are NOT to be searched or plundered: those are my orders.’

‘And mine too,’ said the deep voice. ‘Alive and as captured, no spoiling. That’s my orders.’ “

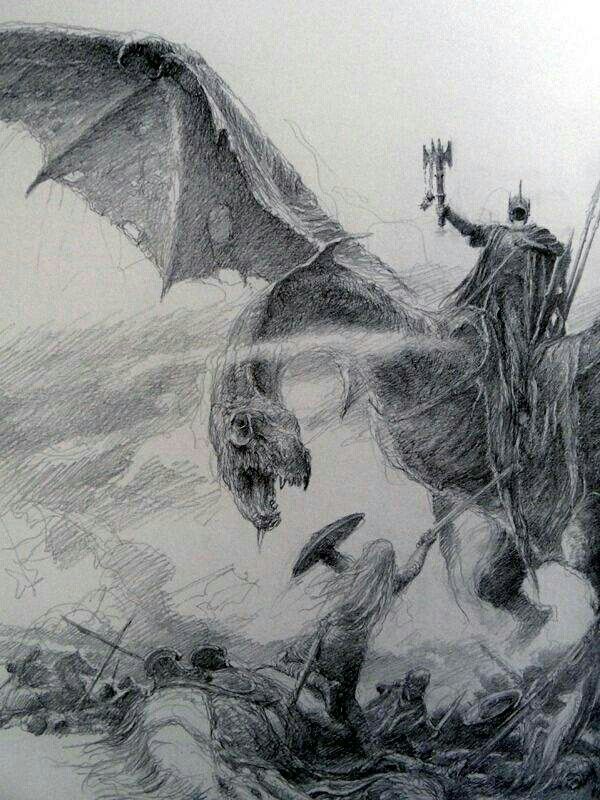

So far, those two main voices—the “deep growl” and the “softer…but more evil”–are just that: voices. And we can tell immediately that they, being the ones given orders and threatening to make reports, are in charge. Shortly, we’ll find that the deep voice belongs to ”a large black Orc, probably Ugluk” and the softer to Grishnakh, “a short, crook-legged creature, very broad and with long arms that hung almost to the ground.”

Why sergeants, not officers? It’s the tone, I think. When Grishnakh proposes taking the prisoners to the east bank of the Anduin, where a Nazgul is waiting, Ugluk replies

“ ‘Maybe, maybe! Then you’ll fly off with our prisoners, and get the pay and praise in Lugburz, and leave us to foot it as best we can through the Horse-country.’ “

“pay and praise” and “footing it” sound to me more like the language of soldiers than those of higher ranks, but there’s something more to their talk. Ugluk sneers at the Nazgul and Grishnakh replies:

“ ‘Nazgul, Nazgul,’ said Grishnakh, shivering and licking his lips, as if the word had a foul taste that he savoured painfully. ‘You speak of what is deep beyond the reach of your muddy dreams, Ugluk.’ “

There is a fear in this that’s a little surprising: aren’t the Nazgul on the same side as Grishnakh, at least?

There is a rivalry between the two groups as well—and clearly even between their two masters, as Grishnakh reveals:

“ ‘You have spoken more than enough, Ugluk,’ sneered the evil voice. ‘I wonder how they would like it in Lugburz…They might ask where his strange ideas came from. Did they come from Saruman, perhaps? Who does he think he is, setting up on his own with his filthy white badges? They might agree with me, with Grishnakh their trusted messenger; and I Grishnakh say this: Saruman is a fool, and a dirty treacherous fool.’ “ (all of the text here is from The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 3, “The Uruk-hai”)

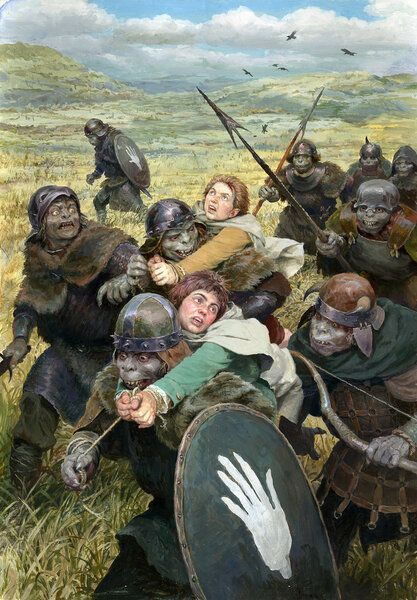

All of this shows a level of internal tension which would not bode well for an alliance between Sauron and Saruman and, when we reach Shagrat and Gorbag, later in the story, there’s even something more and we’ve already seen it in that “We might find something that we can use ourselves.”

So far, the speech of the two Orc leaders has suggested creatures who clearly don’t trust each other, and one is fearful of something on his own side, revealing, as well, that his master, Sauron, is less than impressed by Saruman and his efforts.

And now we find that such sergeants may not even trust their men, as when Shagrat says to Gorbag:

“ ‘…but they’ve got eyes and ears everywhere; some among my lot, as like as not.’ “

But why such wariness? First, because these Orcs are aware that knowledge of the progress of the war in which they’re a part is being kept from them, and it’s not good news:

“ ‘…they’re troubled about something. The Nazgul down below are, by your account; and Lugburz is too. Something nearly slipped…As I said, the Big Bosses, ay,’ his voice sank almost to a whisper, ‘ay, even the Biggest, can make mistakes. Something nearly slipped, you say. I say, something has slipped.’ “

And second because these Orcs, not trusting their masters and perhaps even fearful of them, may have plans of their own—

“ ‘What d’you say?—if we get a chance, you and me’ll slip off and set up somewhere on our own with a few trusty lads, somwhere where there’s good loot nice and handy, and no big bosses.’

‘Ah!’ said Shagrat. ‘Like old times!’ “ (The Two Towers, Book Four, Chapter 10, “The Choices of Master Samwise”)

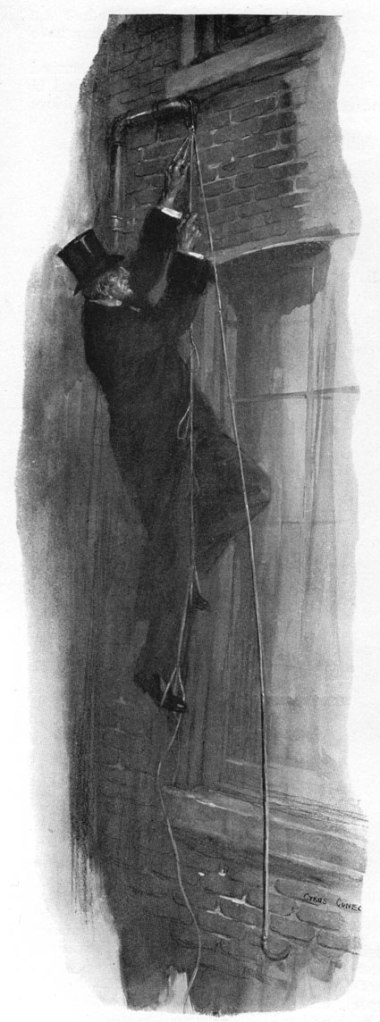

As we’ll see, however, later in the story, Shagrat and Gorbag don’t even trust each other—

“Quick as a snake, Shagrat slipped aside, twisted round, and drove his knife into his enemy’s throat.

‘Got you, Gorbag!’ he cried. ‘Not quite dead, eh? Well, I’ll finish my job now.’ He sprang on to the fallen body, and stamped and trampled it in his fury, stooping now and again to stab and slash it with his knife.“ (The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 1, “The Tower of Cirith Ungol”)

So much for “old times”! But a fitting ending for this posting. Here, on the lowest rung of the social ladder, we see how JRRT shows both the threat of the enemies’ soldiers and, at the same time, undercuts that threat, as we hear the Orcs doing everything from threatening each other, dissing their own leaders and those of their own side, mistrusting each other and their own men, and even plotting to desert and set up their own little kingdoms before cheerfully knifing each other. We might wonder—even if Sauron had won, how long would his empire have lasted, with such allies and underlings?

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

I guess that I don’t have to tell you now: watch your back,

And remember that there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

For more on Orcs and their language, see “Lingua Orca”, 16 April, 2025.