Tags

Algernon Blackwood, billyblind, boggart, Captain Blood, cat, Catherine of Braganza, Charles I, Charles II, Dorchester, Dorset, Errol Flynn, George Jeffreys, ghost, Glastonbury Abbey, Glastonbury Tor, James, King Arthur, Lucy Walter, M.R. James, Maiden Castle, Monmouth, Nell Gwynn, Peter Beagle, rebellion, Sedgemoor, Somerset, Tamsin, Two Men in a Trench

If you had never seen a ghost and probably didn’t believe in them, what would convince you? How about a ghost cat?

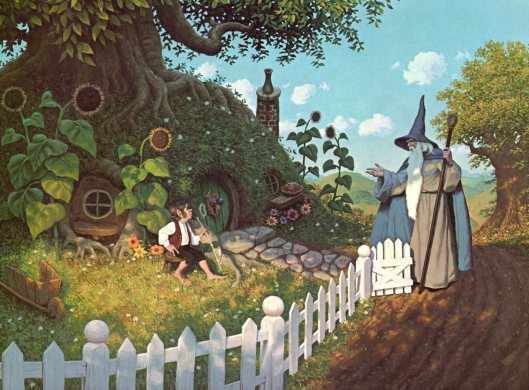

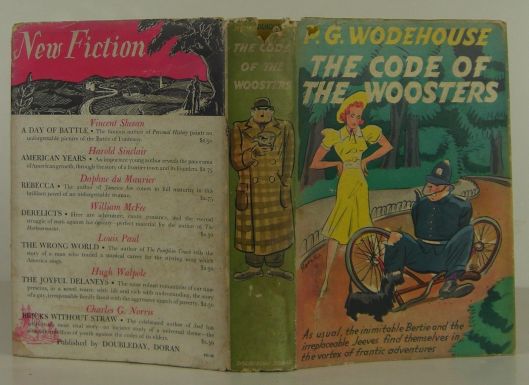

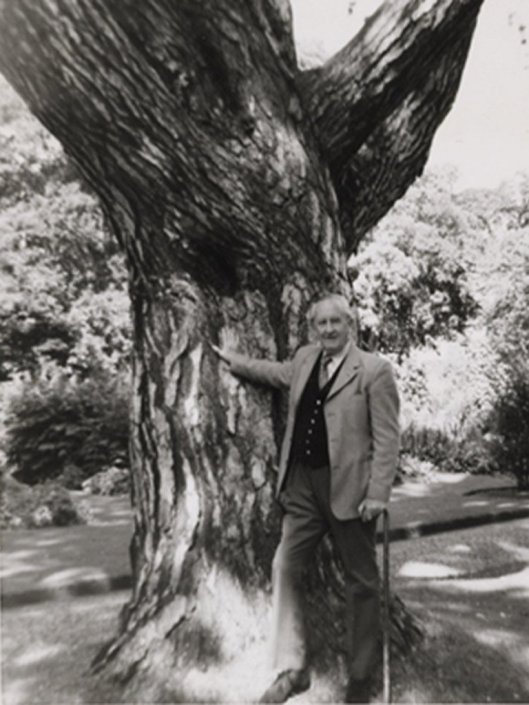

In Peter Beagle’s

Tamsin (1999),

13-year-old Jenny Gluckstein encounters one and it’s only the beginning of a wonderfully rich and, this being a novel by Peter Beagle, a little melancholy, ghost story.

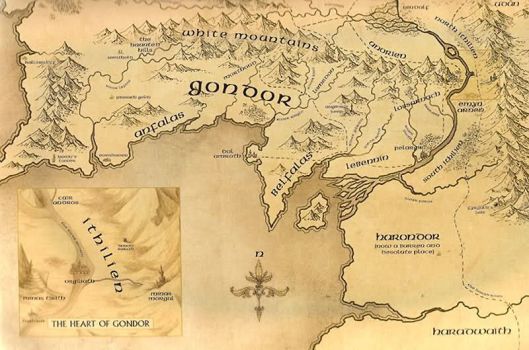

We don’t do spoilers, but what we’d like to do—oh, and, by the way, Welcome, dear readers, as ever!—is, first, to recommend this novel, which begins in New York City, but is mainly set in Dorset,

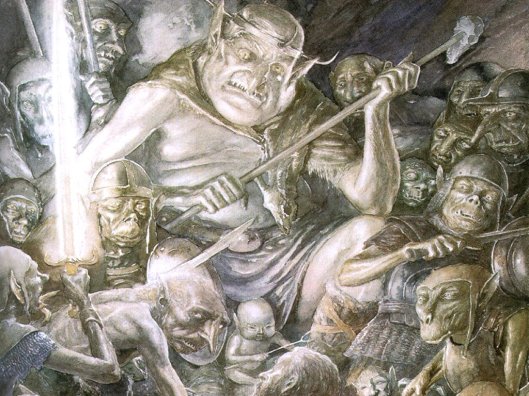

in the southwest of England. If you’re interested in spooks and spirits of all kinds, England is a wonderful place to explore, and the southwest is especially haunted (if you believe in such things—we’re neutral, ourselves, but love a good ghost story). Just look at this massive Iron Age hill fort near Dorchester, called locally, “Maiden Castle”—what lives there at night?

[And speaking of good ghost stories, some of our favorites are by M.R. James (1862-1936) and Algernon Blackwood (1869-1951). Click on the names to access the links so that you can sample their work for yourself, if you don’t know them already.]

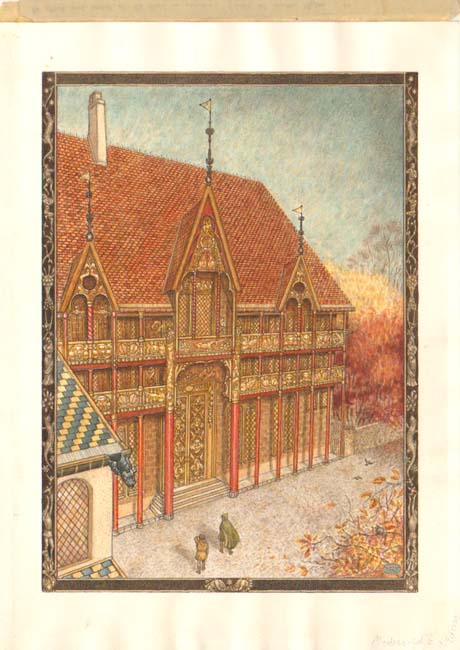

Jenny is transplanted from New York to Dorset because her mother’s second husband is an English agricultural specialist who is hired to rebuild a 350-year-old farm in Dorset. Jenny is, initially, very unhappy with the move—especially when her closest friend, Mr. Cat, must spend 6 months quarantined before being allowed into England. Things slowly begin to change, however, as she makes friends with her two new stepbrothers and finds that the ancient house holds more than her new family, including a boggart, the billyblind, and four ghosts (including that cat).

The ghosts are ectoplasmic survivors of a tragic period in the history of southwest England which all begins with Charles II (1630-1685).

After his father, Charles I, had been executed in London in January, 1649,

his son, Charles, had led an exile’s life until, in 1660, he was invited to return to Britain and reign as Charles II.

Unfortunately for the country, although Charles was married to the Portuguese princess, Catherine of Braganza (1638-1705),

they produced no heirs. Charles also had a long string of mistresses, including the most famous, Nell Gwynn (1650-1687),

and one of them, Lucy Walter (c1630-1658)

gave him a son, James (1649-1685),

whom Charles not only acknowledged, but made, among other things, the Duke of Monmouth.

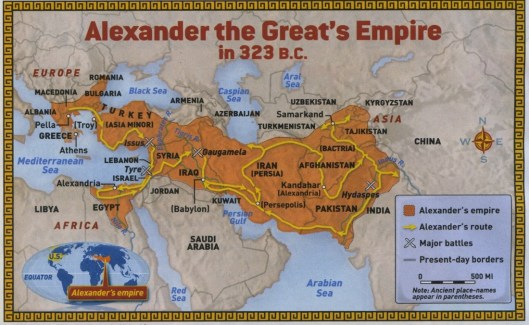

This James had somehow come to believe that his father, Charles, had secretly married his mother, thereby making him the legitimate heir to the throne of England. His uncle, also named James (1633-1701),

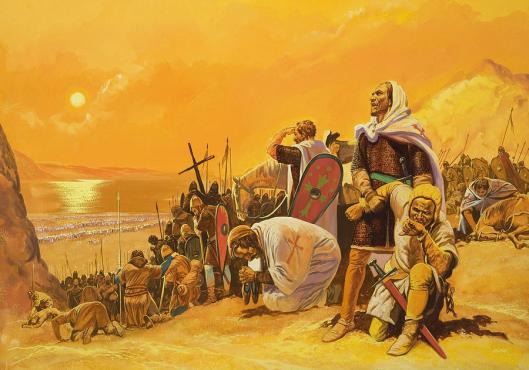

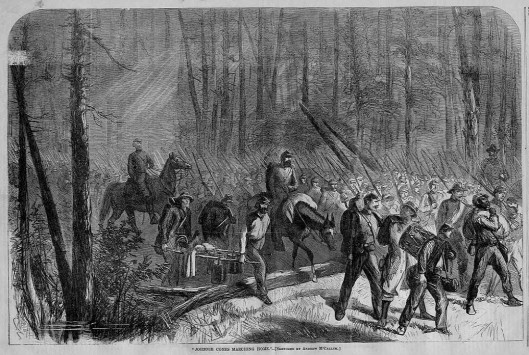

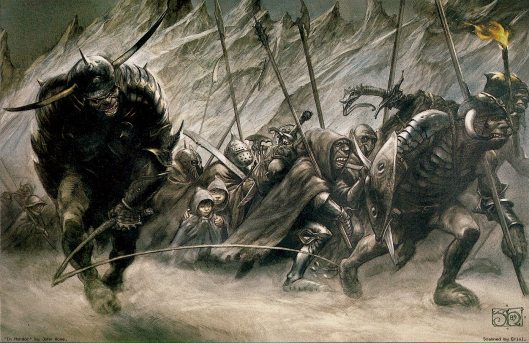

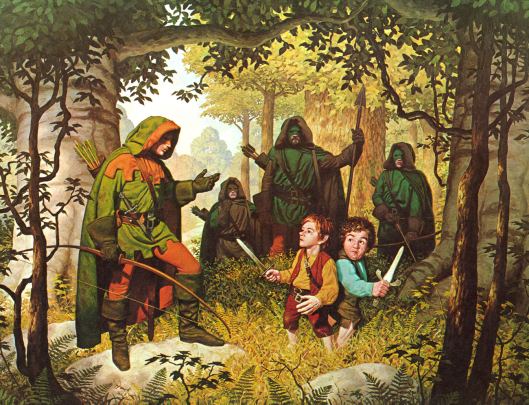

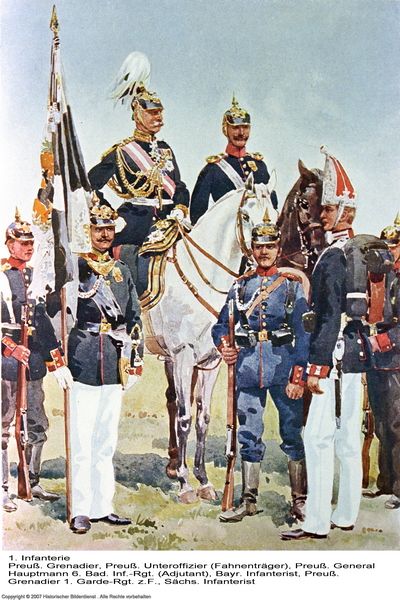

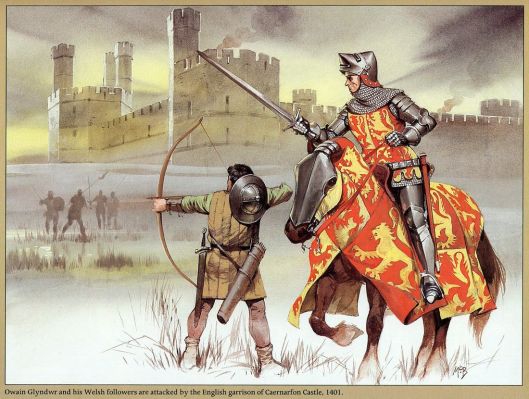

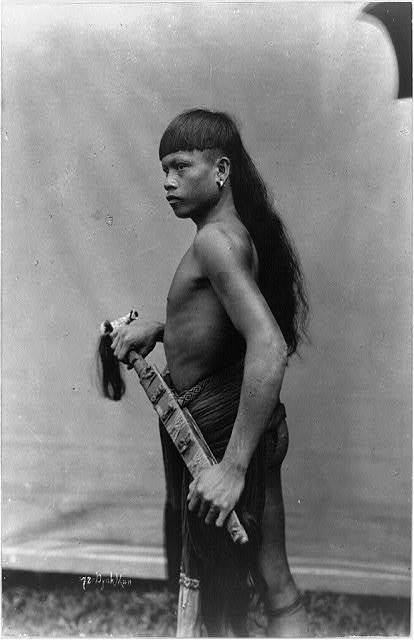

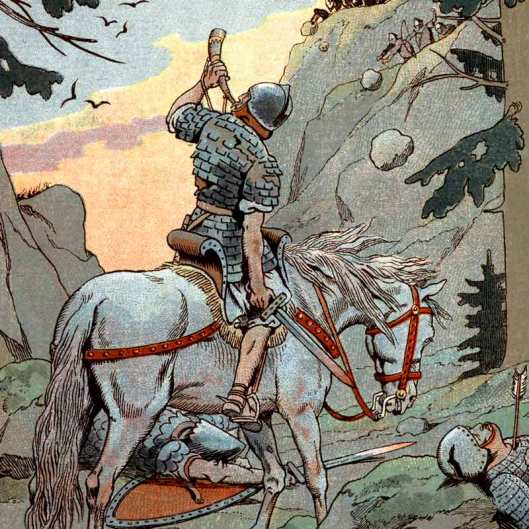

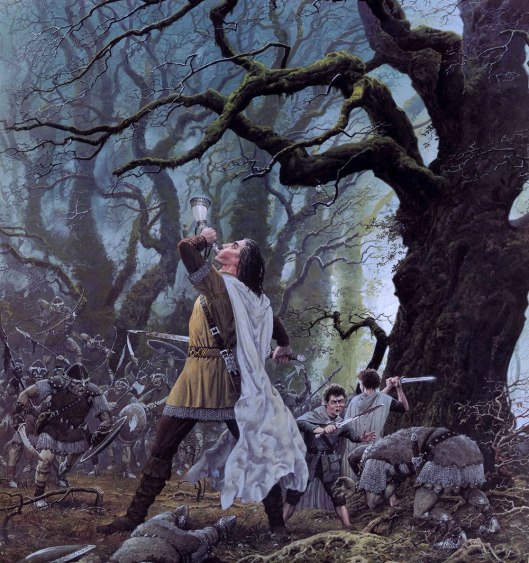

asserting that his older brother, Charles, appeared to have no legitimate heir, claimed the throne for himself upon his brother’s death. This did not please the Duke of Monmouth, who, believing that he had support in the southwest of England, raised a rebellion there against his uncle. He had only very limited resources, and much of his little army was armed with improvised weapons, many of them repurposed farm equipment.

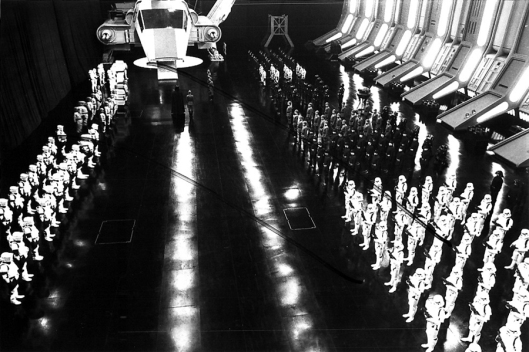

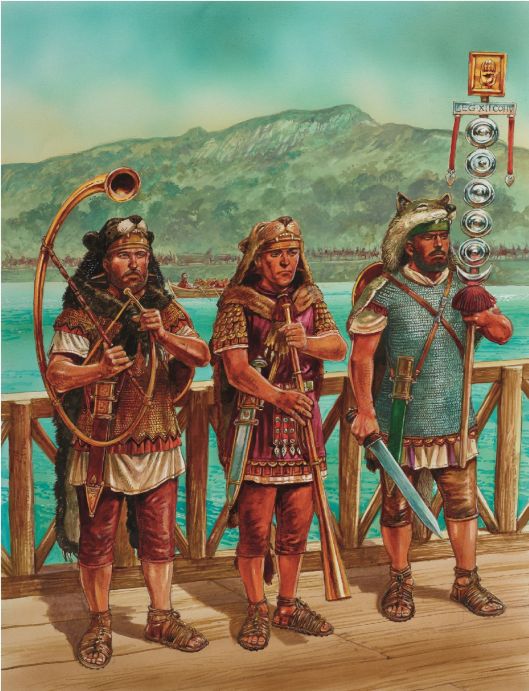

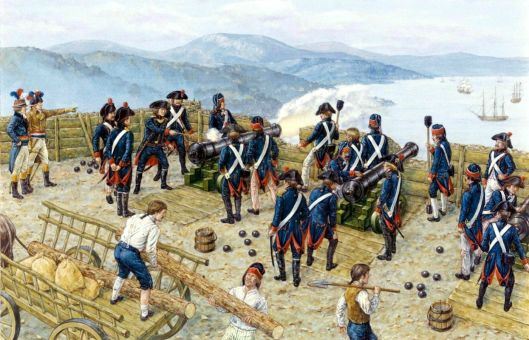

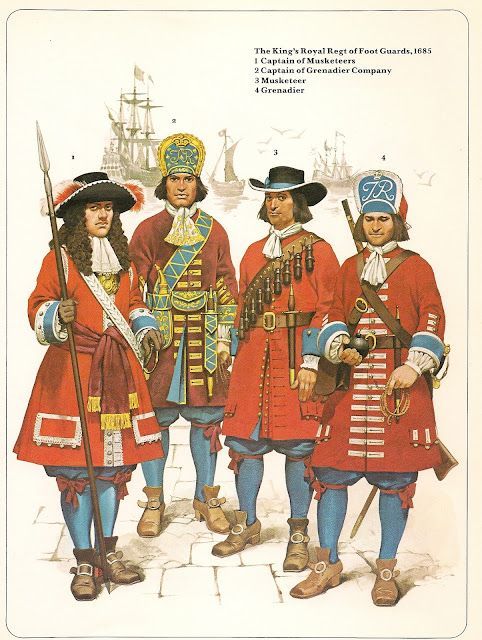

Opposing these was a detachment of the Royal Army,

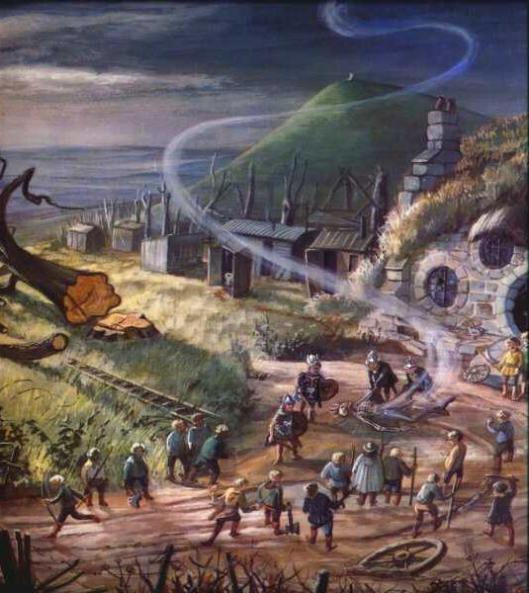

trained professional soldiers. The only battle of this brief campaign occurred not in Dorset, but in the shire to the northwest, Somerset,

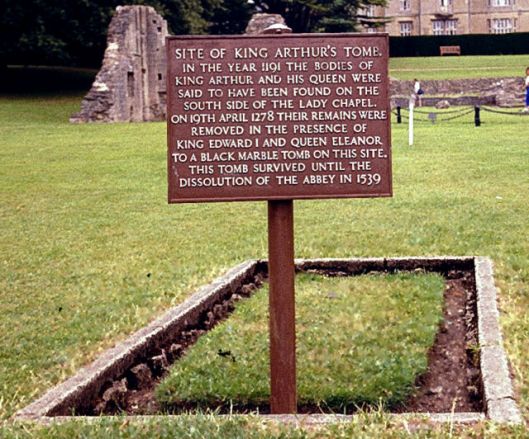

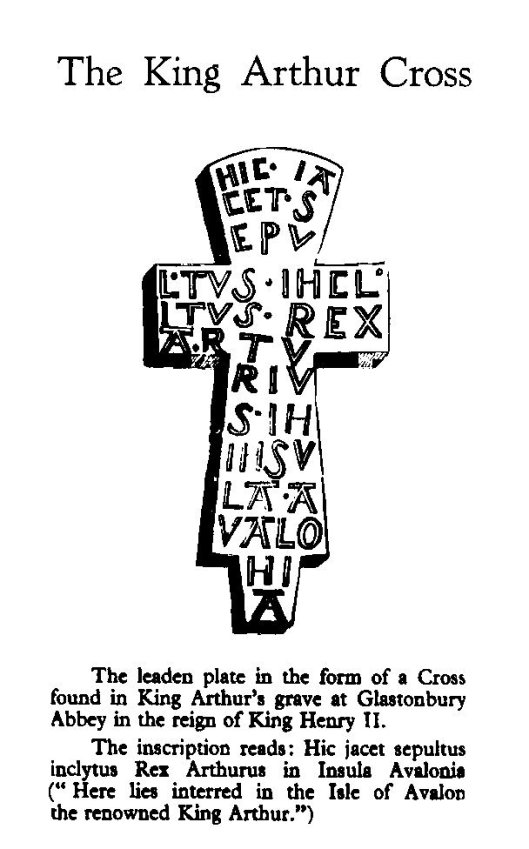

which, in itself is a rather spooky place. After all, in the 12th century, the monks of Glastonbury Abbey claimed that they had happened upon the grave of King Arthur

and they had a lead cross (from the coffin) to prove it.

Even if it’s not spooky, Glastonbury is an impressive place—just look at Glastonbury Tor, with the remains of the 14th-century church of St Michael atop it.

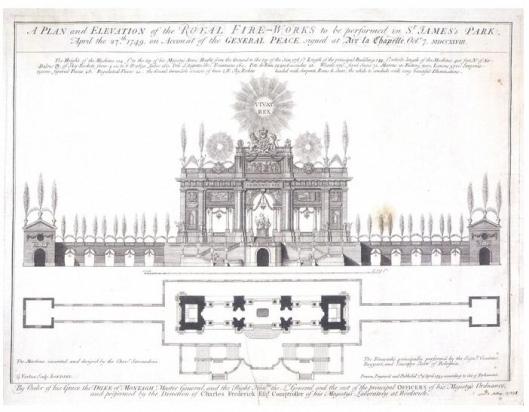

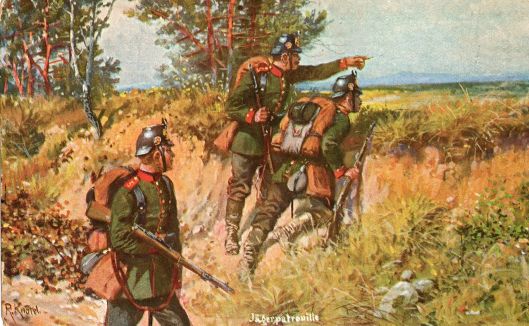

Monmouth knew that, to have any chance of raising more support, he would have to deal with that detachment of redcoats sent to stop him, but, with his own army’s limitations, the best way to even the odds was to attempt a night attack, one of the most difficult maneuvers possible. Unfortunately, although the Royal Army was initially surprised, the mist which covered the battlefield, along with an uncertain knowledge of the terrain, and the lack of discipline among Monmouth’s troops,

as well as the steadiness of the King’s soldiers,

led to a complete defeat of Monmouth’s army, which immediately disintegrated, while Monmouth and his chief followers fled for their lives.

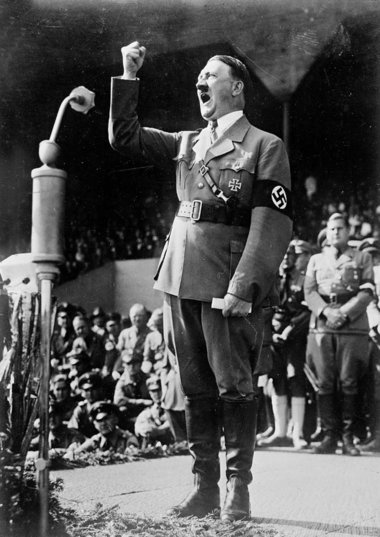

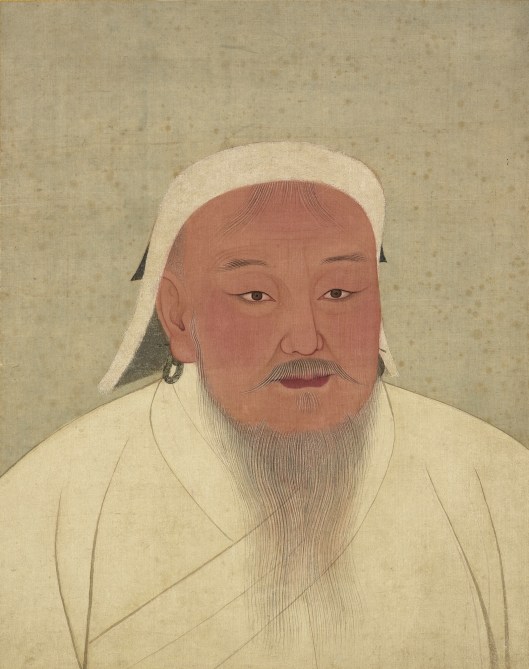

Monmouth was soon captured and brought before his uncle, James, who was less than avuncular in his reaction

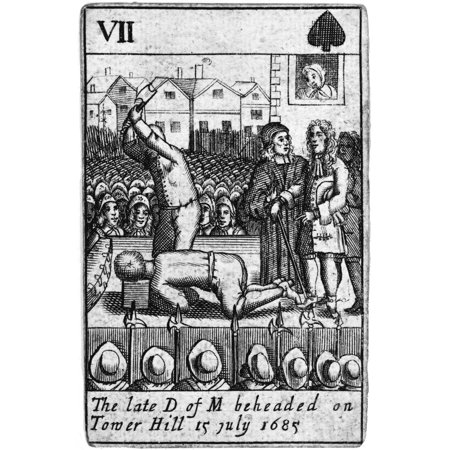

and, very soon afterward, Monmouth was beheaded.

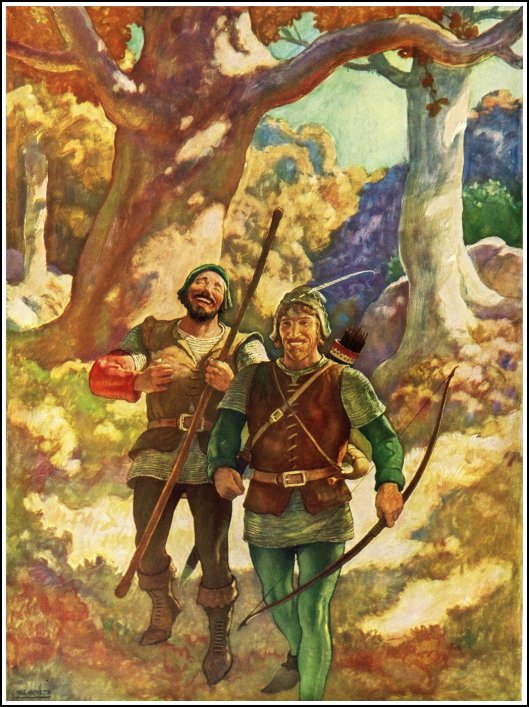

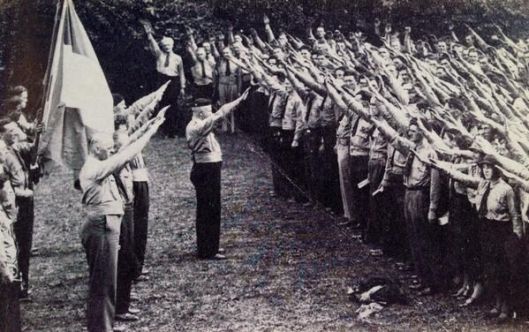

Not content with ending the rebellion, James sent a five-man commission of judges to the region to rout out all opposition to his reign. This commission was headed by the Lord Chief Justice, George Jeffreys, First Baron Jeffreys (1645-1689).

Jeffreys, from the records, was a very thorough man, but a very biased one, as well, and several hundred people across the region were executed after brief trials,

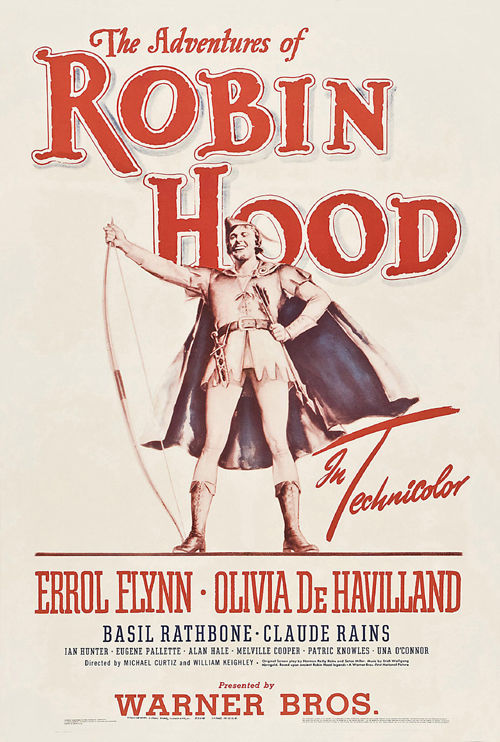

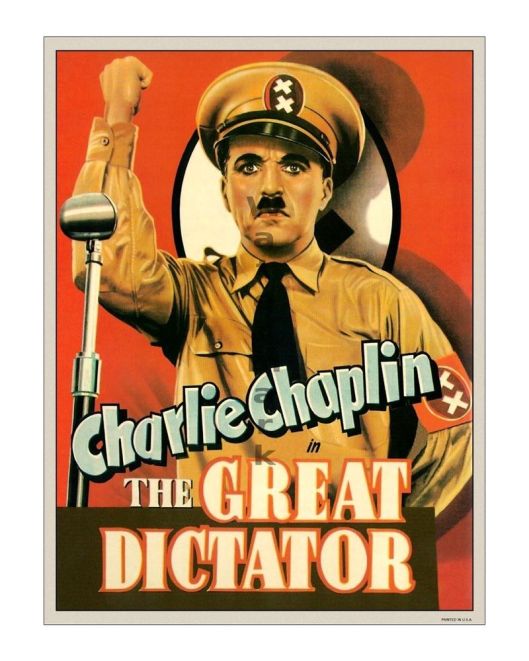

others being shipped as virtual slaves to the Caribbean. (The swashbuckling adventure film, Captain Blood (1935), with Errol Flynn, is about one of the latter—a doctor who helps a wounded escapee from Sedgemoor and suffers for it.)

Jeffreys then becomes the villain of Tamsin, having developed a passion for Tamsin Willoughby, whose family farm is the one which Jenny’s stepfather is hired to restore, during the period now known as the “Bloody Assizes”. Tamsin and Jeffreys and Tamsin’s lover, Edric, are trapped in a kind of terrible time warp and it’s Jenny who—but wait—we said no spoilers, and we mean it!

This is a book to read and reread and now, with a little historical background from us, we hope you enjoy it as much as we have.

MTCIDC

CD

ps

If you would like to know more about the Battle of Sedgemoor, the Two Men in a Trench team of Tony Pollard and Neil Oliver have a fun battlefield archaeology program on it. Here’s the LINK.