Tags

Artillery, Belgium, Cathedral, Cloth Hall, Dale, Esgaroth, Great War, howitzers, Laketown, Lonely Mountain, No Man's Land, Smaug, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien, trenches, Ypres

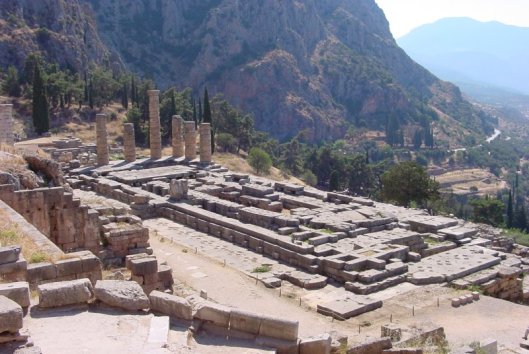

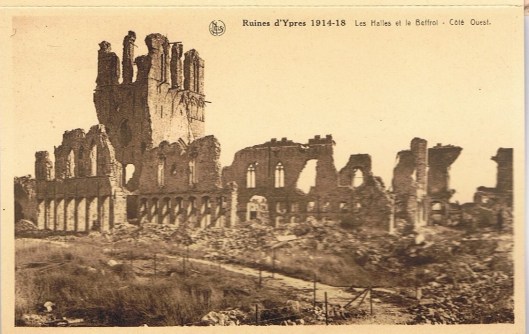

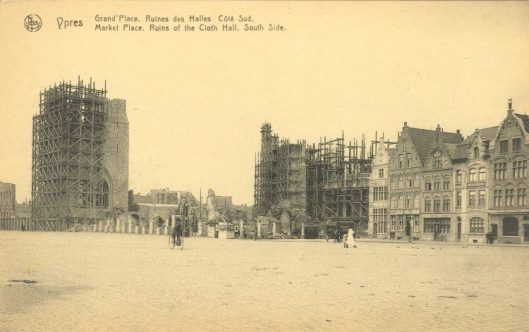

Here is a postcard of the town of Ypres, in southern Belgium, in the years before the Great War, with its famous Cloth Hall and cathedral.

The Cloth Hall was begun in 1200 and finished in 1304, being a center of the woolen trade in the region.

The cathedral was begun in 1230 and finished in 1370.

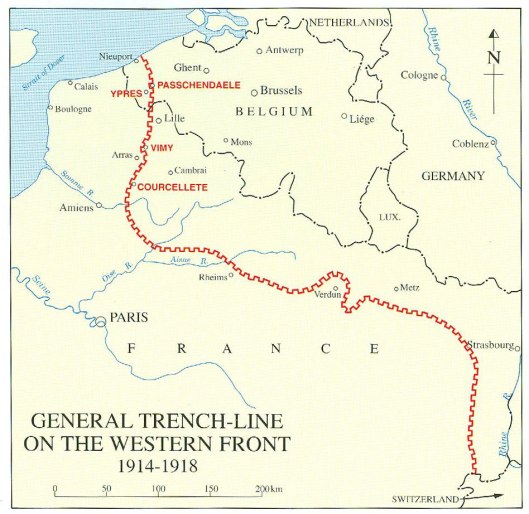

Then the Great War began and Ypres was just behind Allied lines.

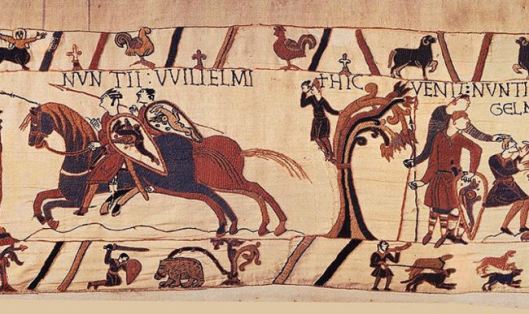

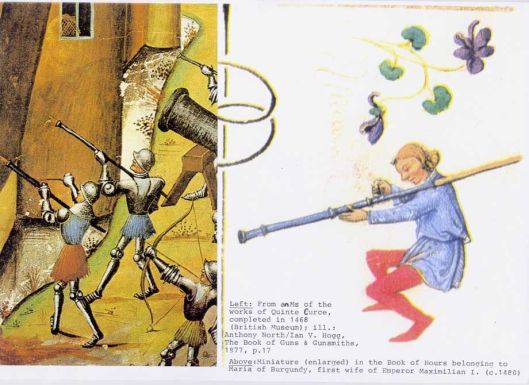

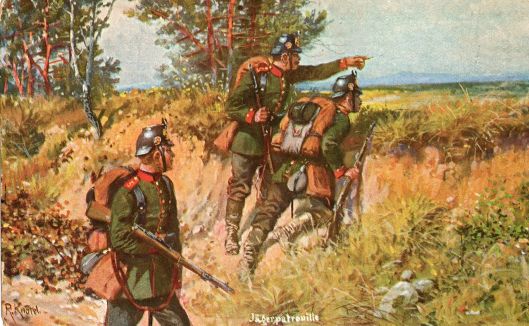

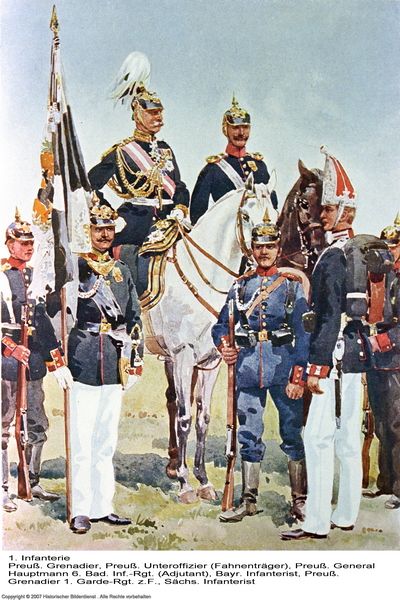

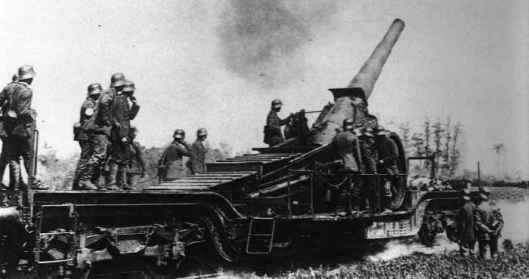

Artillery had begun in the Middle Ages, as something which looks like a high school science experiment (plus armor).

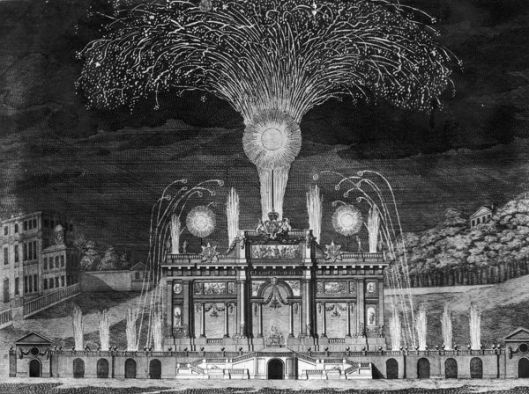

By 1914, it was much bigger and much more efficient.

(The German says, “Our Growlers!”—perhaps a soldier’s slang word for heavy howitzers like these?)

And, as the war progressed, bigger and more efficient yet.

And even more so—to the point where some guns became so big and heavy that only railways could move them around.

Needless to say, when shells from such guns hit Ypres, the damage they caused was enormous.

And not only to Ypres, but to the whole region—entire villages disappeared, as did forests, landscapes became moonscapes.

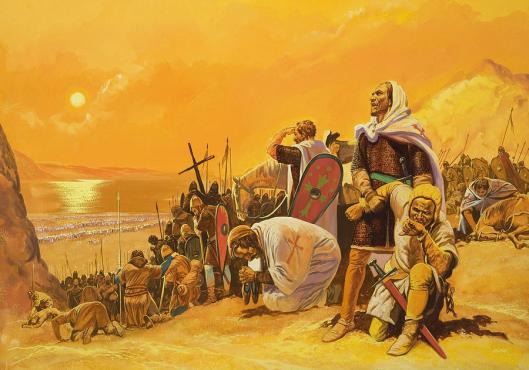

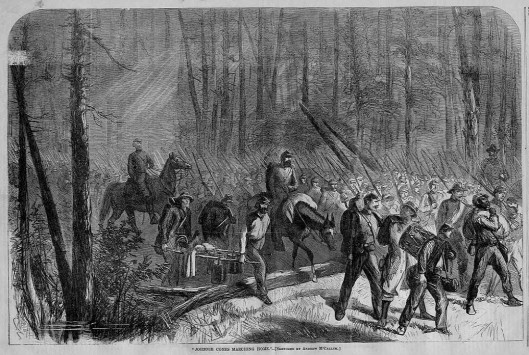

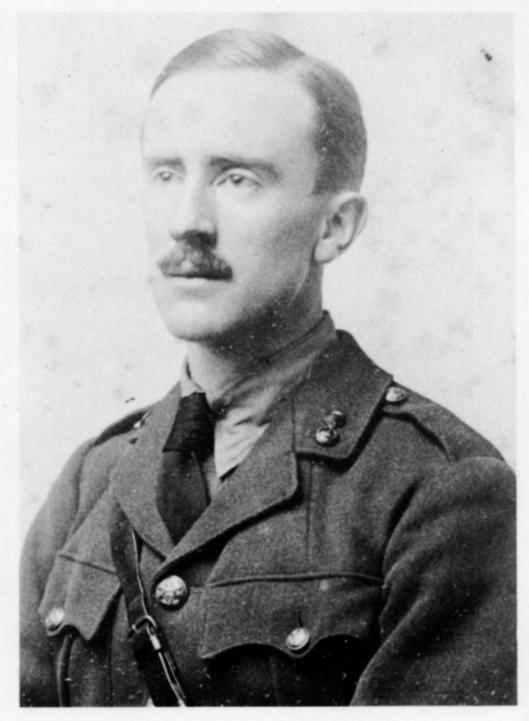

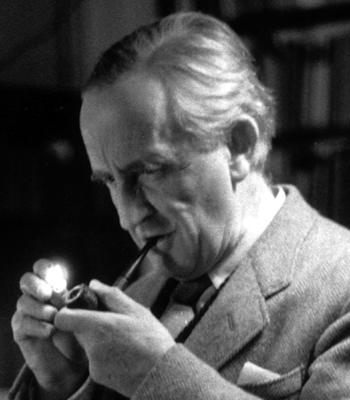

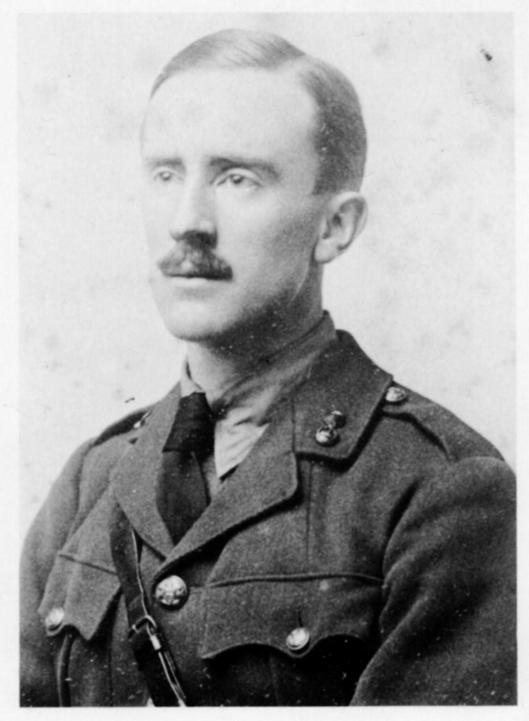

For some months in 1916, Second Lieutenant Tolkien walked through, lived through, this devastated world,

which took many years to be repaired.

And, in the meantime, the economies of Europe suffered, with so much damaged or shifted to war work, and governments left with enormous debts, both the victors and the vanquished.

This devastation made us think about another devastation, first described by Thorin in Chapter One of The Hobbit, and, of course we wondered if JRRT thought of the damage caused by the endless, pitiless bombardments as he wrote about the ruin brought by a dragon.

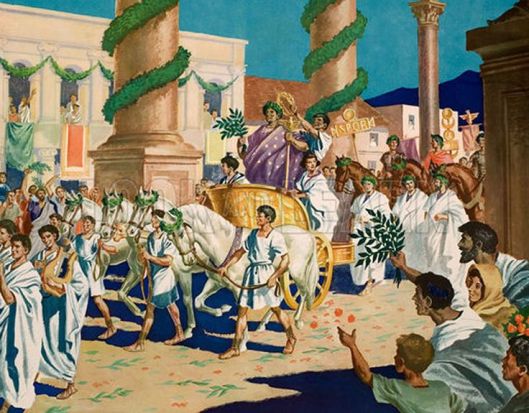

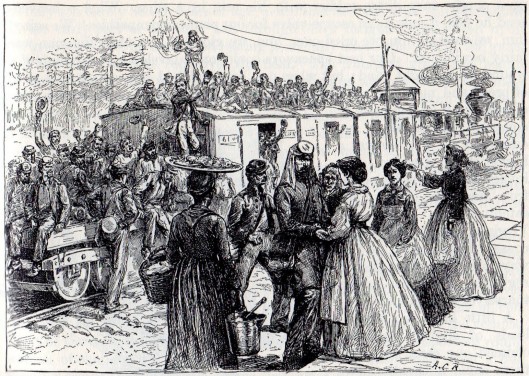

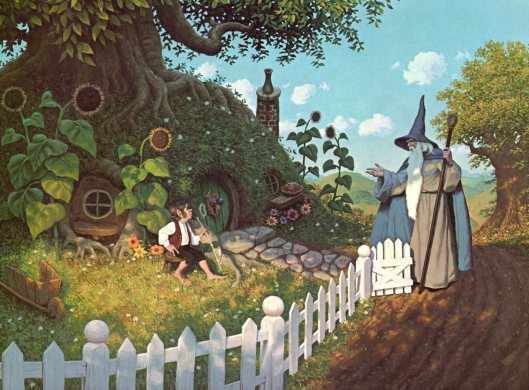

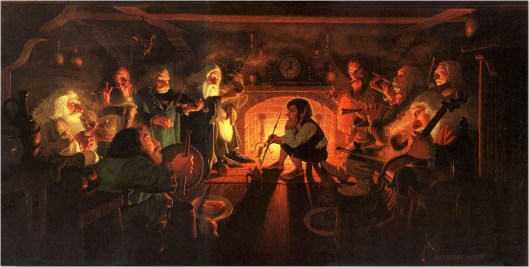

Thorin begins, as we did at the opening of this posting, showing a peaceful, prosperous world:

“Altogether those were good days for us, and the poorest of us had money to spend and to lend, and leisure to make beautiful things just for the fun of it, not to speak of the most marvellous and magical toys, the like of which is not to be found in the world now-a-days. So my grandfather’s halls became full of armour and jewels and carvings and cups, and the toy market of Dale was the wonder of the North.”

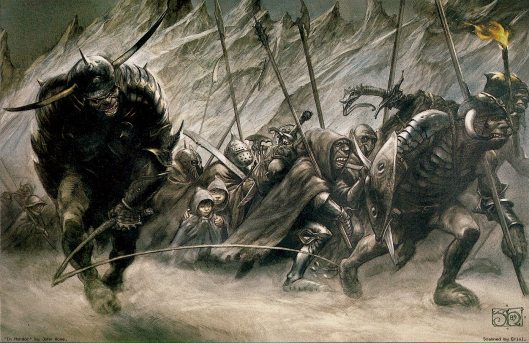

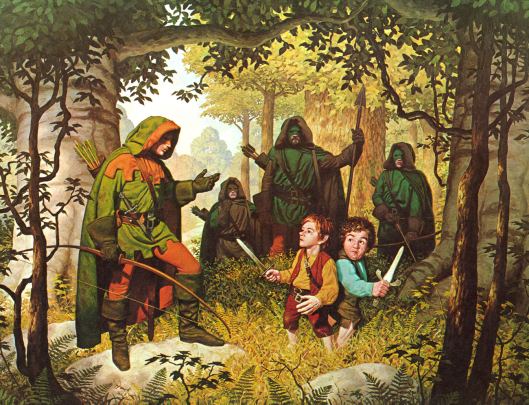

But, just as the Great War came to the ridges north of Ypres, so Smaug came down upon the town of Dale just below the Lonely Mountain and to the Mountain, as well:

“Then he came down the slopes and when he reached the woods they all went up in fire. By that time all the bells were ringing in Dale and the warriors were arming. The dwarves rushed out of their great gate; but there was the dragon waiting for them. None escaped that way. The river rushed up in steam and a fog fell on Dale, and in the fog the dragon came on them and destroyed most of the warriors…Then he went back and crept in through the Front Gate and routed out all the halls, and lanes, and tunnels, alleys, cellars, mansions and passages…Later he used to crawl out of the great gate and come by night to Dale, and carry away people, especially maidens, to eat, until Dale was ruined and all the people dead or gone. What goes on there now I don’t know for certain, but I don’t suppose any one lives nearer the Mountain than the far edge of the Long Lake now-a-days.”

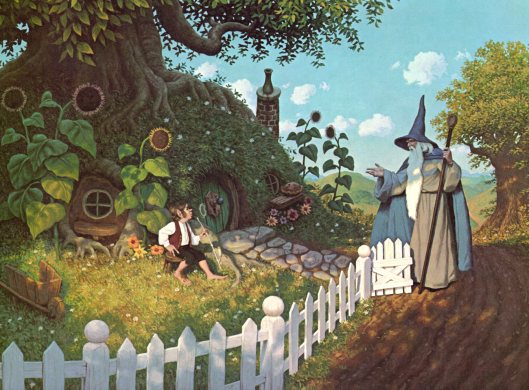

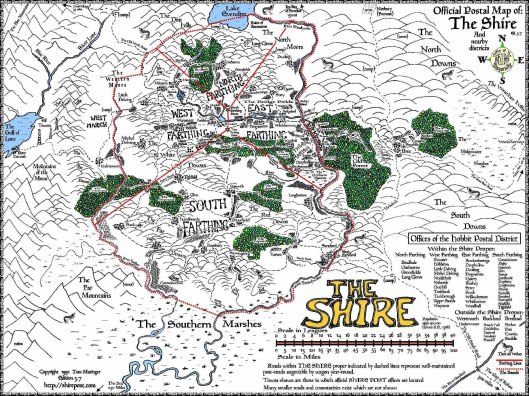

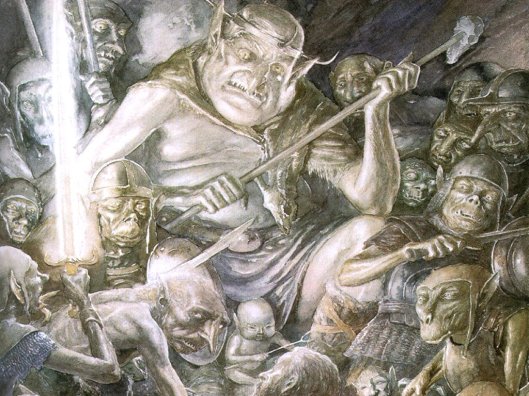

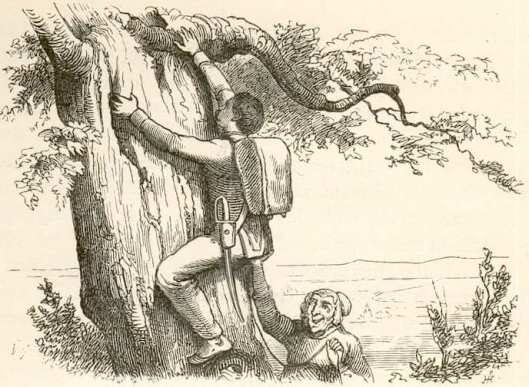

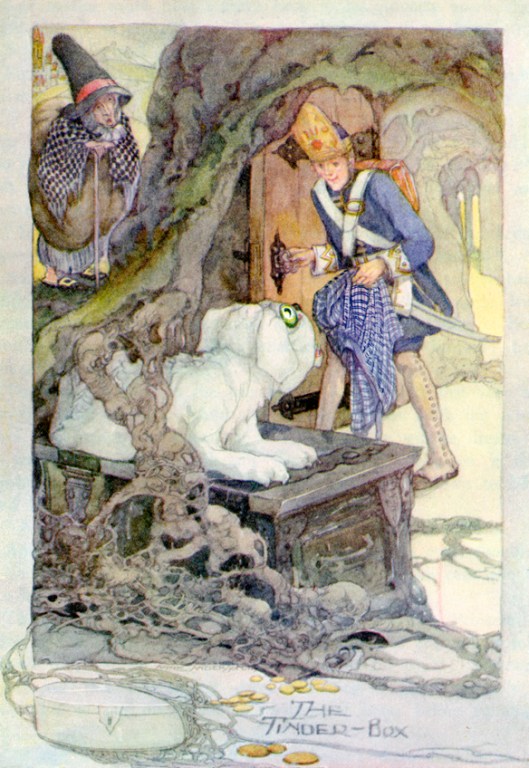

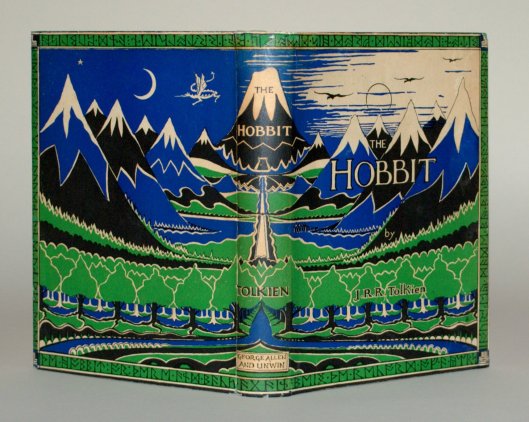

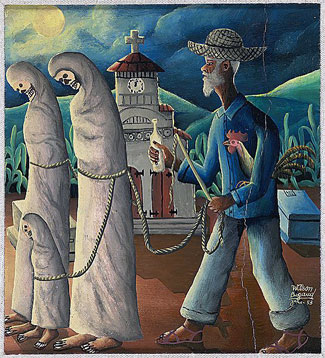

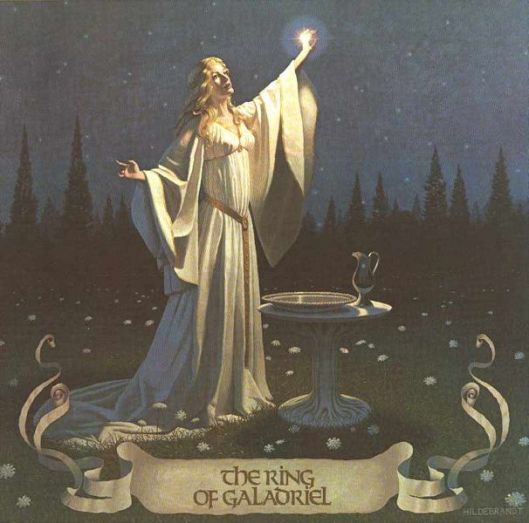

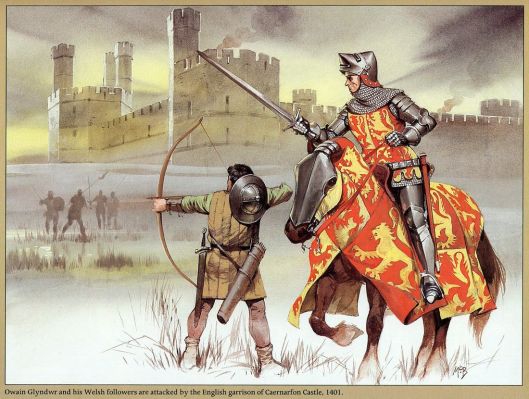

Thorin is correct about this: Dale is ruined and abandoned (you can see the remains of the town on the right hand side of this illustration) and the Mountain has only one inhabitant.

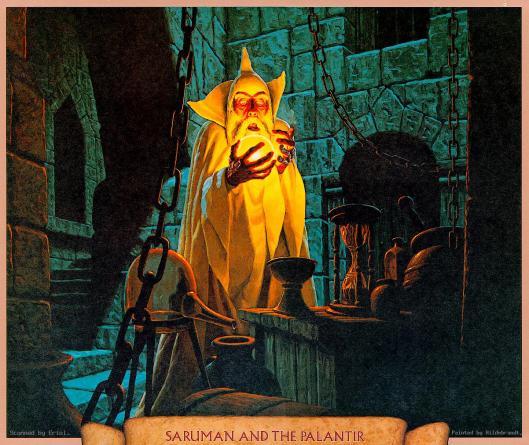

When Bilbo disturbs him and steals a cup, Smaug goes on a second rampage, flying as far south as Lake-town:

“Fire leaped from the dragon’s jaws. He circled for a while high in the air above them lighting all the lake…Fire leaped from the thatched roofs and wooden beam-ends as he hurtled down and past and round again…Flames unquenchable sprang high into the night. “ (The Hobbit, Chapter Fourteen, “Fire and Water”)

And, even when Bard’s arrow brings him down, Smaug causes a final wave of destruction:

“Full on the town he fell. His last throes splintered it to sparks and gledes. The lake roared in. A vast steam leaped up, white in the sudden dark under the moon. There was a hiss, a gushing whirl, and then silence. And that was the end of Smaug and Esgaroth…”

Just as certain parts of Europe were destroyed and their economies stunted by the Great War, we can hear, in Thorin’s words, that the same has happened to Dale and the Lonely Mountain: with no dwarves and no men to make the “armour and jewels and carvings and cups”, not to mention the “most marvellous and magical toys”, the whole economy of the area to the north of the Long Lake was completely destroyed. Survivors built up Lake-town, but no one dared to revive the trade which had once enriched an entire region.

And, as for the few remaining dwarves:

“After that we went away, and we have had to earn our livings as best we could up and down the lands, often sinking as low as black-smith-work or even coal-mining.” says Thorin.

Although Thorin dies in the struggle to regain what was lost, there is a happy ending of sorts for the dwarves. With Smaug dead, they can finally return, as can men, and rebuild, just as Europe began to rebuild—Ypres restored both Cloth Hall and cathedral in time.

But the dragon would return and all too soon…

Thanks, as always, for reading and

MTCIDC

CD