Tags

A Princess of Mars, Around the Moon, Columbiad, Cyrano de Bergerac, Edgar Rice Burroughs, From the Earth to the Moon, HG Wells, Jules Verne, Mars, Percival Lowell, science fiction, The First Men in the Moon, The Gods of Mars, The War of the Worlds, The Warlords of Mars, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, twenty-thousands-leagues-under-the-sea

Welcome, as ever, dear readers.

Recently, I’ve returned to my long-term project to learn more about Science Fiction, which I began several years ago.

When I began to assemble a reading list (it keeps growing), I knew that it would include older authors like Jules Verne (1828-1905),

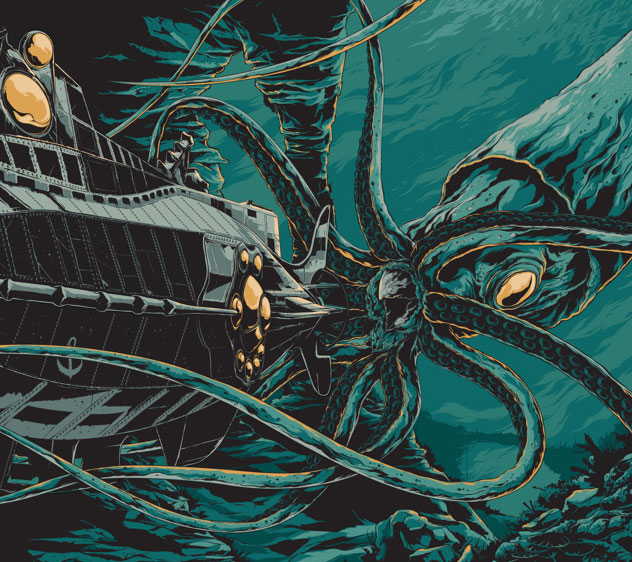

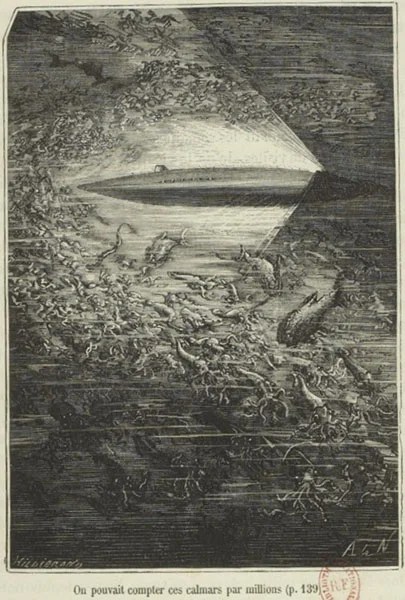

whom I had first met through his novel, Vingt Mille Lieues Sous Les Mers

(first English translation, 1873)

usually (slightly mis-) translated as Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea—but needs a final –s on “Sea-“, which the first English translation, following the original French, added. At first sight, one might think that those masses of leagues were about depth, but, in fact, they were about length: the idea being that the Nautilus, the submarine of the antagonist, Captain Nemo, traveled that distance below the waves during the story—that is 20,000 x 2.5 miles—maybe about two circumferences of the Earth. Here’s the ship from the original French publication—

but, for me, the Nautilus (inspired by an actual submarine experiment in France—see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_submarine_Plongeur ) will always be the ship seen in Disney’s 1954 version of the story.

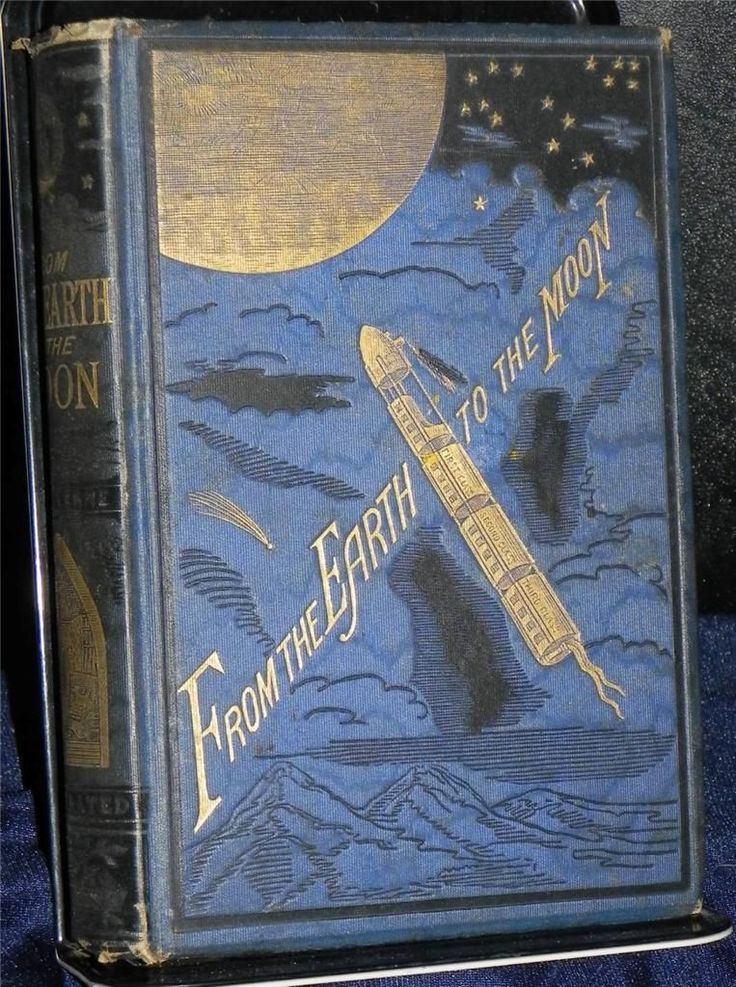

Some years earlier, in 1865, Verne had written De la Terre a la Lune, trajet direct en 97 heures et 20 minutes—From the Earth to the Moon, Direct Route in 97 Hours and 20 Minutes (usually simply translated as From the Earth to the Moon You can read about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/From_the_Earth_to_the_Moon and read an early translation here: https://web.archive.org/web/20110520193116/http://jv.gilead.org.il/pg/moon/ Be aware that this is not a very good translation and cuts the text, as well, but it’s free and will give you a general idea of the story).

(the 1874 translation)

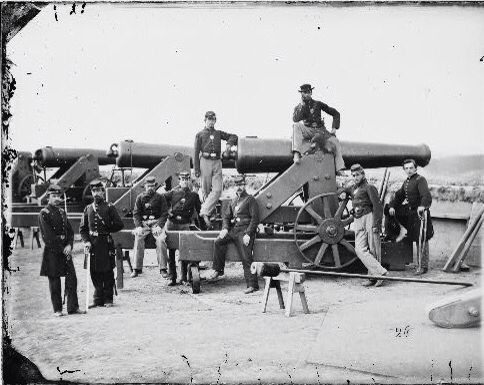

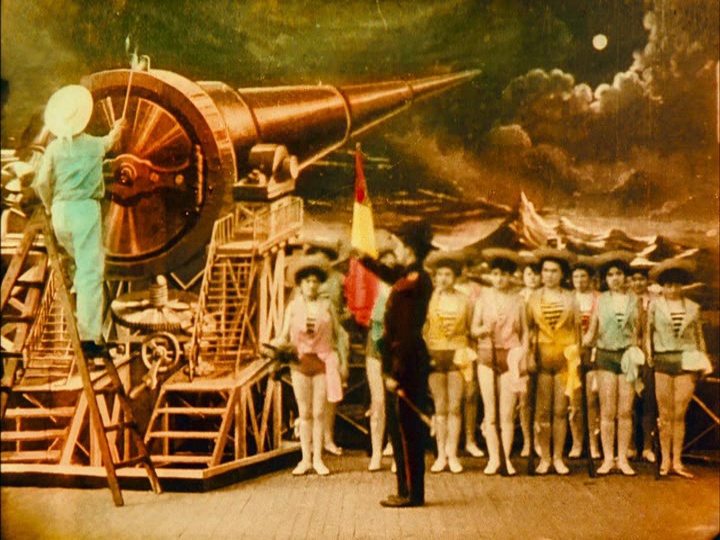

In this adventure, an organization called the “Baltimore Gun Club” constructed a giant cannon

(called a “Columbiad” after this heavy coastal defense gun—only much bigger—for more, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbiad )

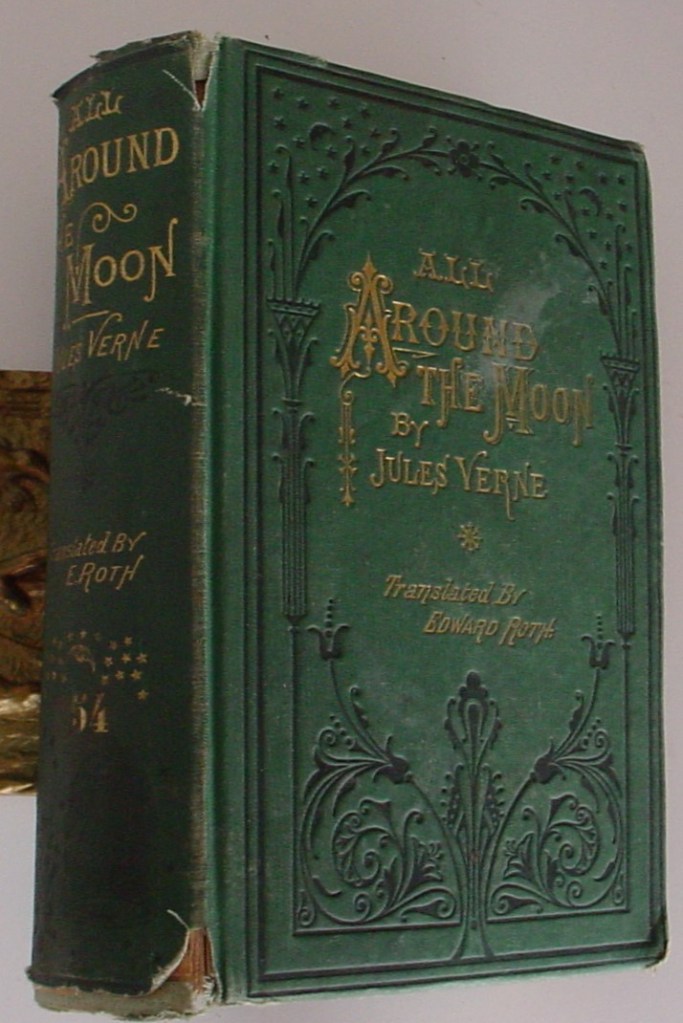

designed to shoot passengers to the Moon. How they are to return is only revealed in the 1869 sequel, Autour de la Lune—Around the Moon—

(the second translation, 1874)

You can read about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Around_the_Moon And you can read the early translation depicted above here: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/16457/pg16457-images.html This book inspired the early French film-maker, Georges, Melies, 1861-1938, to produce his own burlesque version, Le Voyage dans la Lune, 1902, which included that cannon—and a chorus line!)

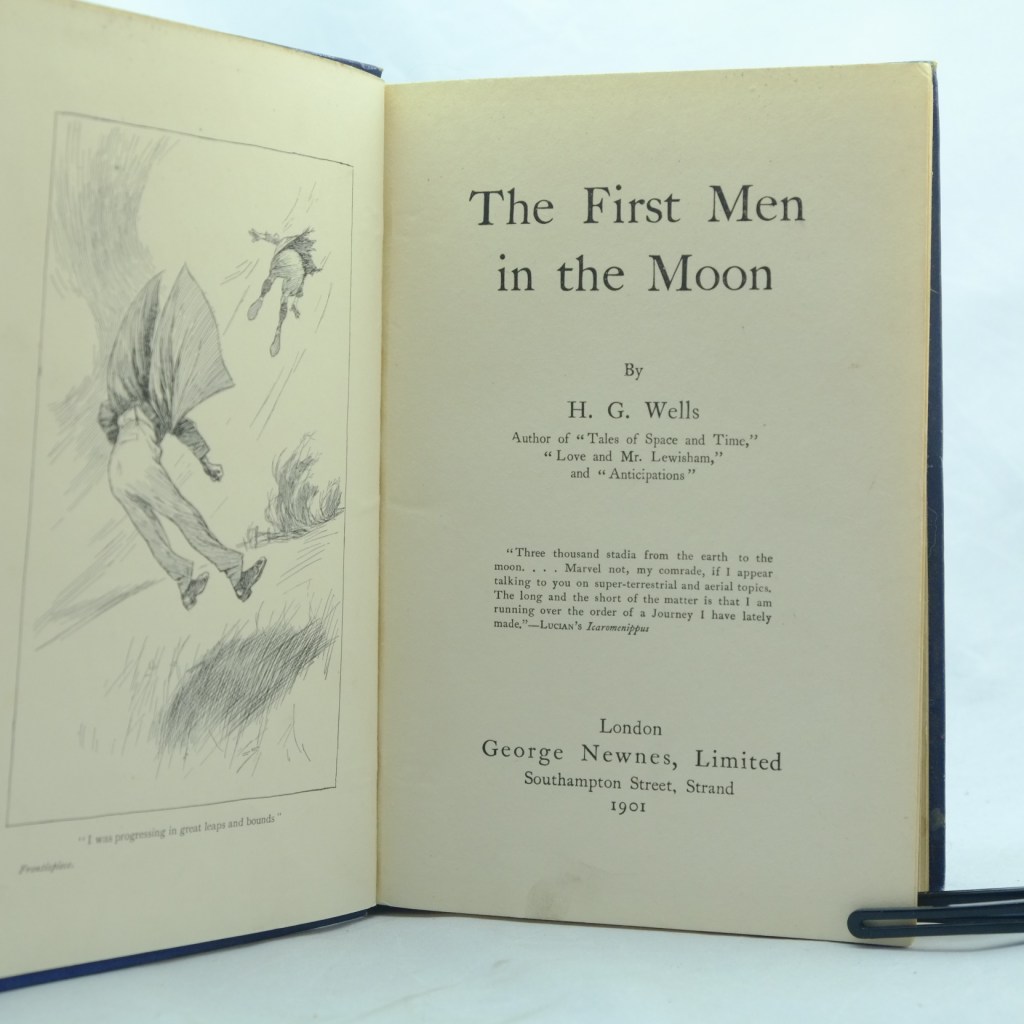

Along with Verne, H.G. Wells, 1866-1946, was on my list, including The First Men in the Moon, 1901.

Wells’ protagonists reach the moon through a man-made anti-gravity material, called “Cavorite”, after its inventor (one of the two lunar travelers), which is attached in carefully-monitored sheets to a steel and glass sphere. You can read the book yourself here: https://ia601308.us.archive.org/2/items/firstmeninmoo00well/firstmeninmoo00well.pdf

(from the original English edition)

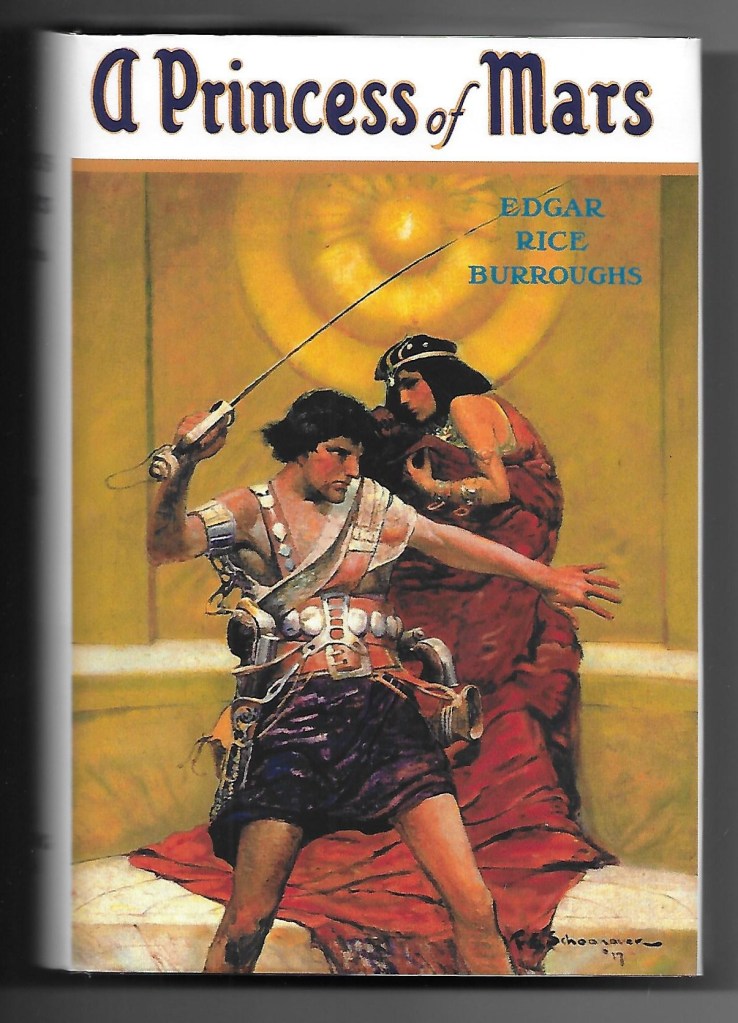

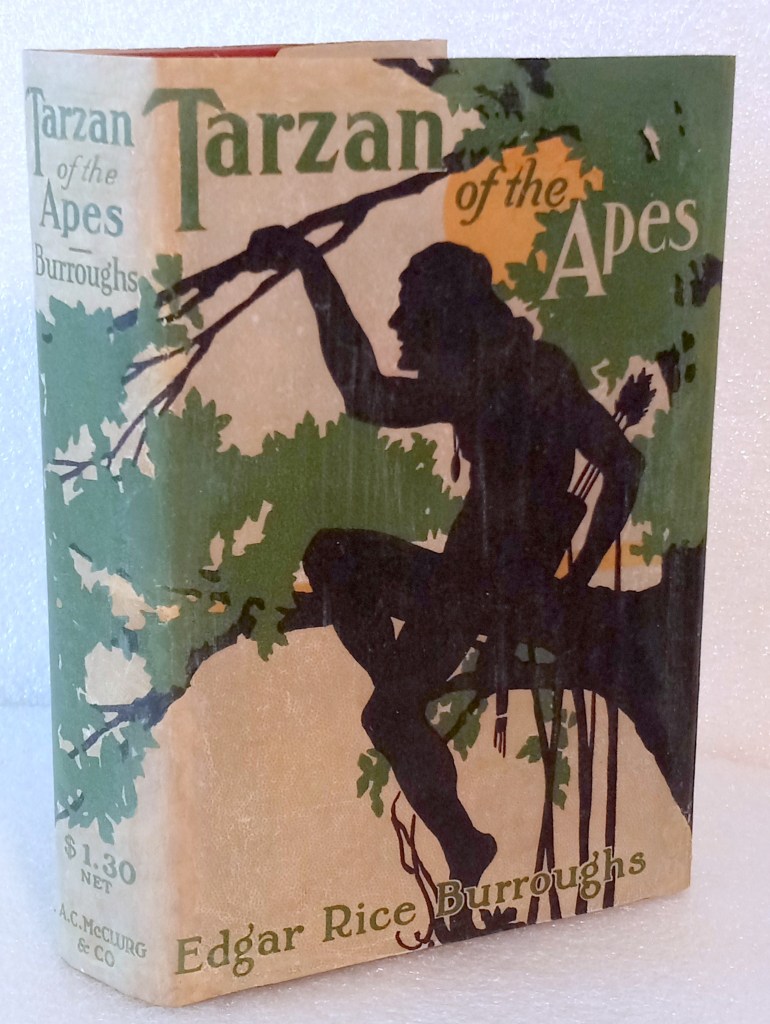

Early in my exploration of science fiction writers, I had read Edgar Rice Burroughs’, 1875-1950, A Princess of Mars (serialized 1912, first book edition, 1917).

(You can read about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Princess_of_Mars and read the story itself here: https://gutenberg.org/cache/epub/62/pg62-images.html )

As I said, I had known Verne already, and Wells from The War of the Worlds, (serialized 1897, first book publication 1898)

(read about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_War_of_the_Worlds and read it here: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/36/pg36-images.html ), but all I knew about Burroughs was

and so I was hesitant, but I was pleasantly surprised that, even with a certain amount of what we might call “period” language (and cultural attitudes), this was a very readable book. (See “Busting Into Mars”, 27 September, 2023, for more.)

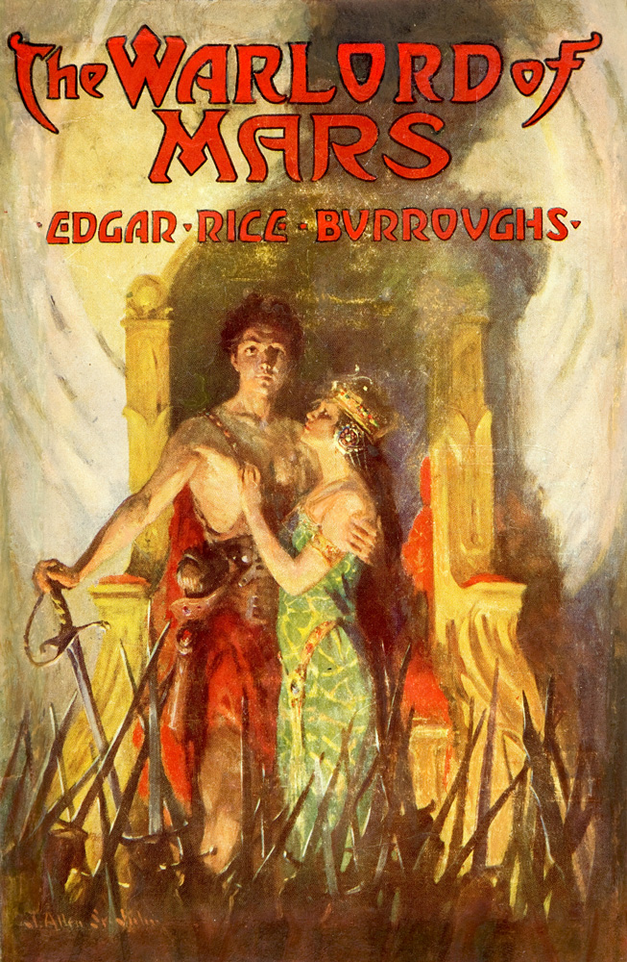

Taking a recent pause from my other reading, then, I tackled the next in Burroughs’ series, The Gods of Mars (serialized 1913, first published as a novel, 1918).

And, again, I found myself sucked in. John Carter, the hero of the previous book, was back and quickly in the thick of it again. (Here it is for you to read: https://archive.org/details/godsofmars02burr )

And, as well, I found that part of what had struck me in the first book caught me again: the attention to the detail of the physical world of “Barsoom” (Burroughs’ local name for Mars).

Burroughs had clearly prepped himself with the latest scientific ideas, many of them from Percival Lowell, 1855-1916, a prominent Victorian astronomer, who had become convinced, having read the work of the Italian astronomer, Giovanni Schiaparelli, 1835-1910, who, in 1877, having closely observed Mars during its nearest approach to Earth, believed that he could see long, straight, intersecting lines across the planet’s surface. He published a map of Mars in which he called these lines “canali”, which has a number of meanings in Italian, including “ducts” and even “gullies”, but also means “channels” and, fatally, “canals”, which was immediately seized upon by some to suggest that Mars was—or at least had been—inhabited—and by people who had the engineering ability to create many-miles-long canals.

(We should probably consider terrestrial canals here, such as that the long-needed, occasionally-attempted 120-mile (193km) Suez Canal, which had only been relatively recently successfully completed in 1869. We might add to this the 61-mile (98km) Kiel Canal, finished in 1895. Could these have appeared as earthly parallels to those who wanted to believe in Martian versions?)

What were they for? As Mars has a large northern ice cap, which grows and recedes yearly, it’s clear that the canals were used to direct melt across the planet. But why? To irrigate a dry planet, of course. In time, Lowell published three books on the subject: Mars (1896—read it here: https://archive.org/details/marsbypercivallo00lowe ), Mars and Its Canals (1906—read it here: https://archive.org/details/marsitscanals00loweuoft/page/n9/mode/2up ), and Mars As the Abode of Life (1908—read it here: https://archive.org/details/marsabodeoflife00loweiala ) They are filled with charts and graphs and illustrations,

piled high to convince his audience that what he observed through his powerful telescope was real.

In reality, none of it was—but it certainly inspired writers like Burroughs, who produced a world with:

1. increasing aridity

2. canals

3. declining civilizations, some of whose elaborate cities had been abandoned, only to be occasionally inhabited by tribes of warrior nomads

4. underground seas

5. 5 races of differently-hued (white, black, green, yellow, red) humanoids (although oviparous) plus masses of creatures, some tamable, some simply monstrous, like the Plant Men who appear in The Gods of Mars, which is, in fact, an ironic title, as what we see are various pretenders to that title, including the Therns, who belong to the white race and who run a kind of confidence game in which they maintain what is supposed to be a peaceful afterlife in a green river valley, but which is, in fact, a feeding ground for those Plant Men and for the fearsome White Apes.

(Michael Whalen—you can see more of his impressive work here: https://www.michaelwhelan.com/ )

Setting these peoples into an increasingly-harsh environment then allowed Burroughs to explain why certain of these peoples—the green ones, in particular—were themselves harsh, as the declining climate turned them into brutal survivalists.

6. sophisticated aircraft and even submarines (for use on the underground waters)—for more on the aircraft, see: https://www.erbzine.com/mag28/2806.html This is from: https://www.erbzine.com/mag/ the weekly on-line magazine devoted to Burroughs and his output. I wish that every one of my favorite authors had people as creative and dedicated at work on websites as rich as this one.

7. sophisticated firearms, but, when it comes to real fighting, it is always swords

For more on things Barsoomian, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barsoom as well as the extensive Erbzine. I’ve already provided the text of The Gods of Mars above, and you can read a plot summary and more here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Gods_of_Mars . There are the occasional creaky moments, but, on the whole, this was as much fun as A Princess of Mars. And there’s an added twist here: it ends as a cliff-hanger.

(This is, in fact, Harold Lloyd, in his comedy Safety Last!, 1923. Overshadowed in time, I would say, by Chaplin, Lloyd was an accomplished comic actor and this film is a pleasure to watch—and laugh at. You can see it here: https://archive.org/details/SafetyLastHaroldLloyd1923.FullMovieexcellentQuality. It’s one of a great number of early films available at the Internet Archive, which, if you read this blog regularly, you know is my go-to place for any number of different things, from silent films like this one to Percival Lowell on Mars—and much more.)

But there is one little problem. Verne’s voyagers travel in what is, basically, an enormous artillery shell. Wells’ two men ride in a sphere powered by some sort of anti-gravity material. Neither of these, I suppose, is really any more convincing than Cyrano de Bergerac’s claim to have visited the Moon using, in his first attempt, bottles of dew in his L’Histoire comique des Etats et Empires de la Lune, 1655 (You can read about Cyrano’s adventures here: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/46547/pg46547-images.html and you can read about the book here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comical_History_of_the_States_and_Empires_of_the_Moon ),

but they at least travel in their bodies. John Carter’s voyage to Barsoom is done through what appears to be an “astral body”:

“ I made the same mighty and superhuman effort to break the bonds of the strange anaesthesia which held me, and again came the sharp click as of the sudden parting of a taut wire, and I stood naked and free beside the staring, lifeless thing that had so recently pulsed with the warm, red life-blood of John Carter.

With scarcely a parting glance I turned my eyes again toward Mars, lifted my hands toward his lurid rays, and waited.

Nor did I have long to wait; for scarce had I turned ere I shot with the rapidity of thought into the awful void before me. There was the same instant of unthinkable cold and utter darkness that I had experienced twenty years before, and then I opened my eyes in another world, beneath the burning rays of a hot sun, which beat through a tiny opening in the dome of the mighty forest in which I lay.” (The Gods of Mars, Chapter 1, “The Plant Men”)

This isn’t explained, but, however it’s done, Carter is able to use his terrestrial muscles, developed under a much denser gravity, to bounce around the Martian surface, pilot aircraft, and swing a sword, so I, for one, am able to perform a “willing suspension of disbelief” and see how the story gets off that cliff in The Warlord of Mars.

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

When visiting, remember that Mars’ gravity is only 38% of Earth, so look before you leap,

And remember, as well that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

Although he was wrong about those canals, Lowell was a creative and energetic scientist, as well as a highly-intelligent and well-read man—and a very interesting man, as well. You can read more about him here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Percival_Lowell If you find him as intriguing as I do, here’s the Internet Archive page on his works—which include more than writings about Mars: https://archive.org/search?query=creator%3A%22Percival+Lowell%22