As ever, dear readers, welcome.

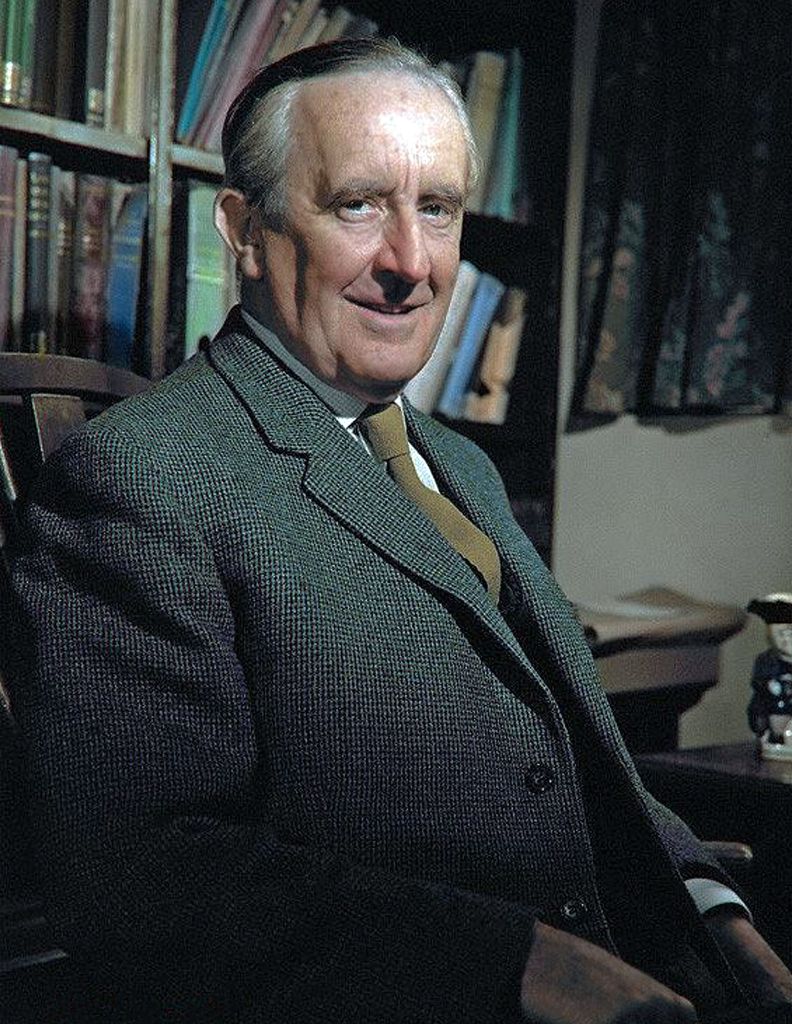

I was very pleased when the new, expanded edition of The Letters of JRR Tolkien appeared in 2023,

not only for what new information might be contained in that word “expanded”, but also as, having used my paperback copy of the first edition to the point where, although the pages were still intact, the whole book seemed a little tired, as if it had been employed a little more often than it would have preferred.

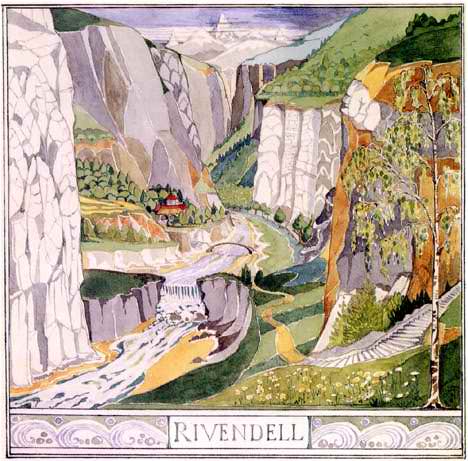

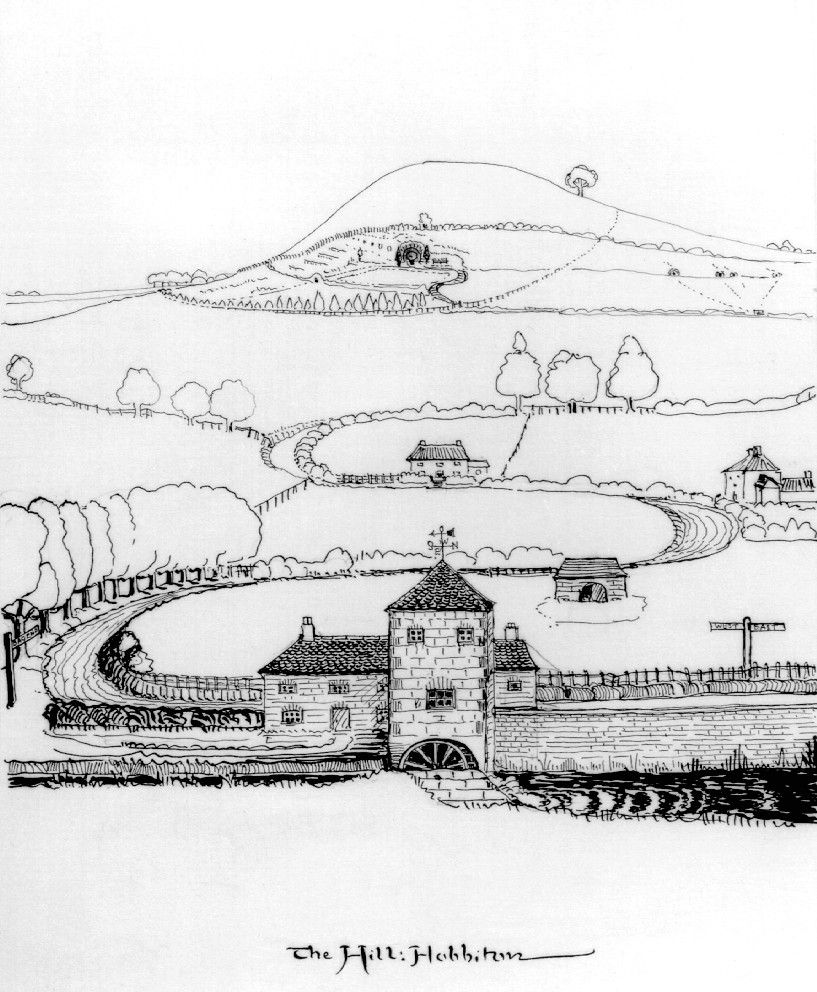

When I first opened this new edition, I immediately paged through to what I had hoped was among the expanded letters: “From a Letter to Forrest J. Ackerman” (“Not dated; June 1958”, Letters, 389-397).

This, as Humphrey Carpenter’s note tells us, was “Tolkien’s comments on the film ‘treatment’ of The Lord of the Rings”.

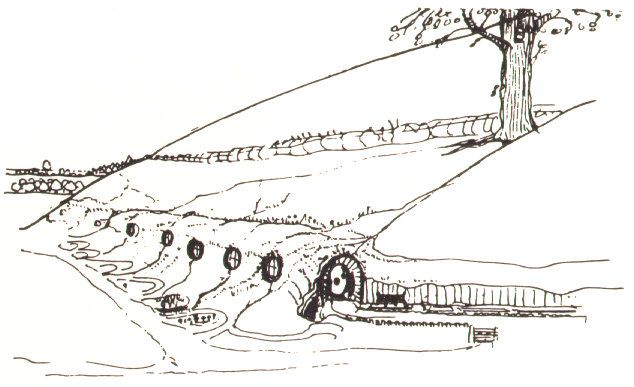

Ackerman doesn’t appear in Carpenter’s Tolkien biography, but he does appear in several letters, including the long excerpt, and Carpenter makes reference to him, as “agent for the film company” (Letters, 628). In fact, he was a major figure in the American world of fantasy/science fiction/horror in the 1950s and 1960s, including being the editor of an early fan magazine, Famous Monsters of Filmland, 1958-1983, which provided an impressionable young man with this particularly haunting image—

(This is Lon Chaney, Sr., in the missing London After Midnight, 1927, which you can read about here: https://silentology.wordpress.com/2022/10/31/everything-you-ever-wanted-to-know-about-london-after-midnight-practically/ If, like me, you love silent film, this is a good site to learn from. You can read about the rather tangled history of Famous Monsters here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forrest_J_Ackerman and about Ackerman here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forrest_J_Ackerman )

From the additional material available in the new edition, we can see that Tolkien liked the visual samples with which he was presented, but—there’s no other word for it—appalled by the “treatment”, of which he wrote:

“If Z. [Zimmerman, the writer of the treatment] and/or others do so [that is, read Tolkien’s comments], they may be irritated or aggrieved by the tone of many of my criticisms. If so, I am sorry (though not surprised). But I would ask them to make an effort of imagination sufficient to understand the irritation (and on occasion resentment) of an author, who finds, increasingly as he proceeds, his work treated as it would seem carelessly in general, in places recklessly, and with no evident signs of any appreciation of what it is all about…” (From a Letter…,389)

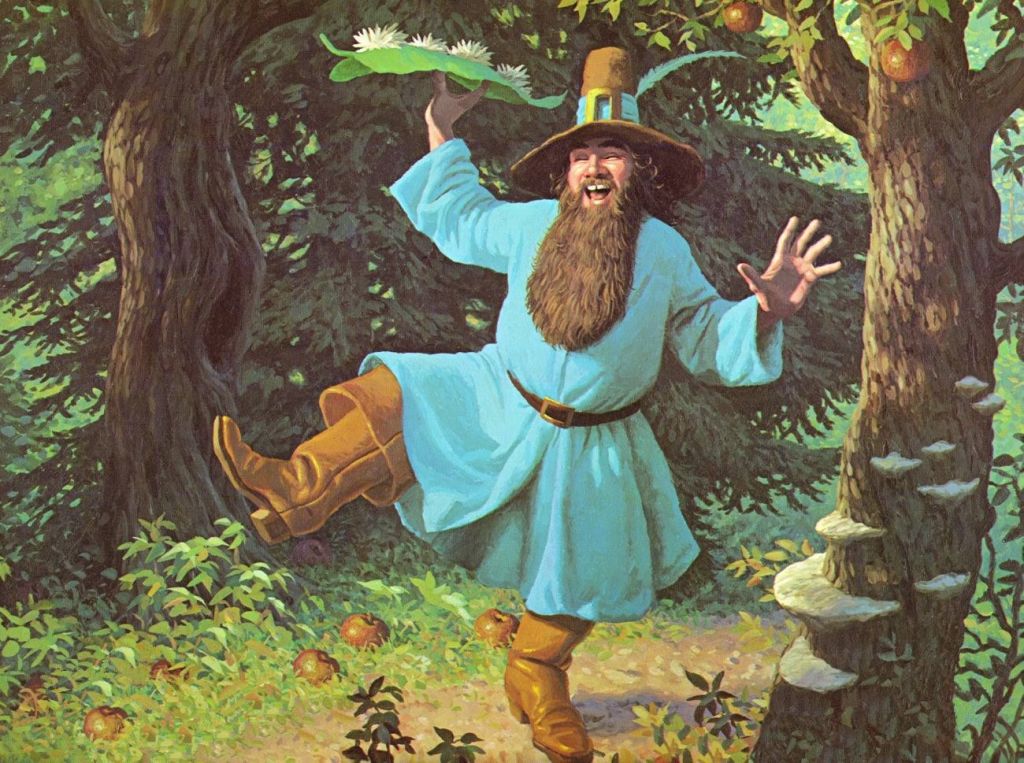

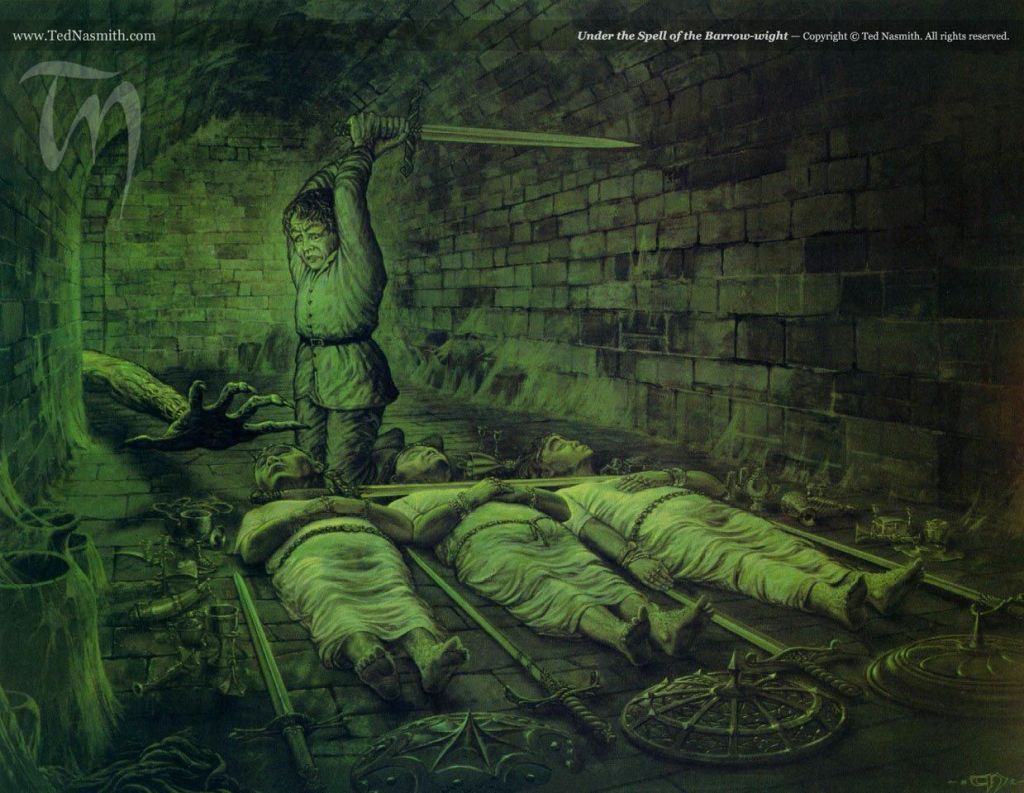

What I had hoped for was the complete letter, as, from what has actually been printed, Tolkien tells us, in his criticism, just what he might have wanted in a film of The Lord of the Rings and, in the process, provides us with a different perspective on his perspective. Certainly, what is included underscores what he wrote in the beginning of the letter, and something I take from it is that the writer has imagined much of the book as being downright clownish—as in Tolkien’s comments on the presentation of Tom Bombadil:

“7. The first paragraph misrepresents Tom Bombadil. He is not the owner of the woods; and he would never make any such threat.

‘Old scamp!’ This is a good example of the general tendency that I find in Z to reduce and lower the tone towards that of a more childish fairy-tale. “ (Letters, 391)

Add to this Tolkien’s later comment on the appearance of Merry and Pippin as Saruman’s “door-keepers”:

“14. Why on earth should Z say that the hobbits ‘were munching ridiculously long sandwiches’?” (Letters, 396)

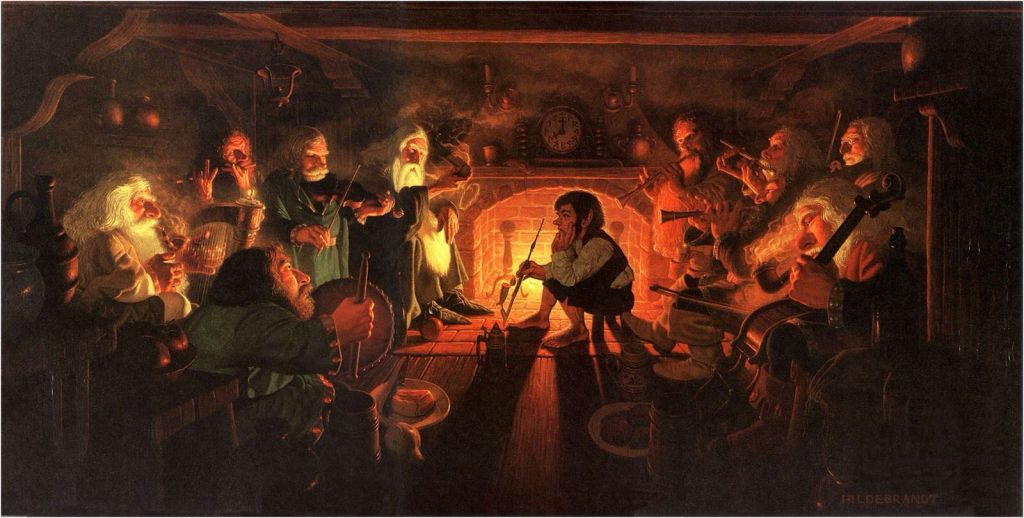

(Michael Herring—you can see more of his work here: https://www.artnet.com/artists/michael-herring/ )

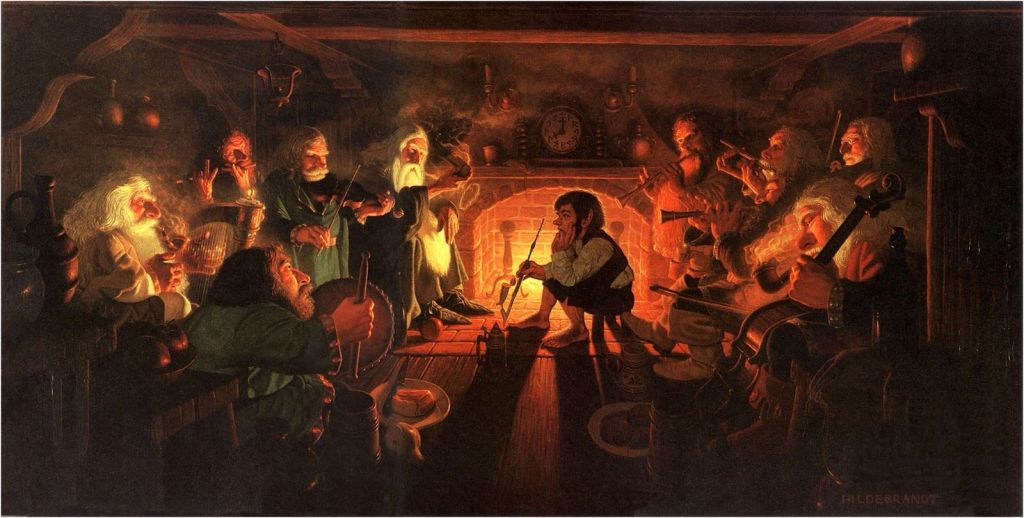

Of himself, Tolkien once wrote:

“[I] have a very simple sense of humour (which even my appreciative critics find tiresome)” (from a letter to Deborah Webster, 25 October, 1958, Letters, 412)

So he was not against comedy in general:

“I return Rayner’s [Rayner Unwin, the son of Sir Stanley, Tolkien’s publisher] remarks with thanks to you both. I am sorry he felt overpowered, and I particularly miss any reference to the comedy, with which I imagined the first ‘book’ [that is, The Fellowship] was well supplied. It may have misfired. I cannot bear funny books or plays myself, I mean those that set out to be all comic; but it seems to me that in real life, as here, it is precisely against the darkness of the world that comedy arises…” (letter to Sir Stanley Unwin, 31 July, 1947, Letters, 172)

Tolkien could even be a practical joker—see Humphrey Carpenter, JRR Tolkien: A Biography, 134, for more on this.

And yet we can see, from his Ackerman comments, that, when it came to his creative work, he was not only serious, but expected others to take it seriously—to treat it seriously—as well.

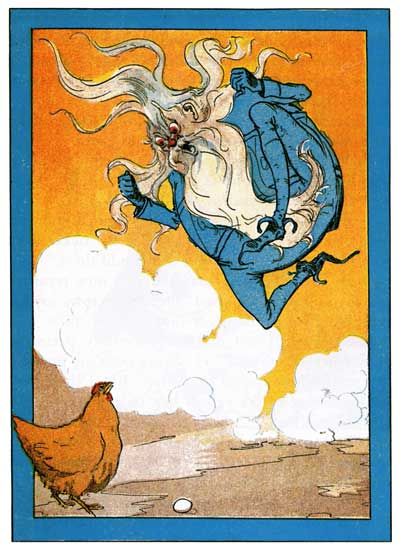

So what are we to make of the portrayal of Radagast the Brown in The Hobbit of P. Jackson and Co.?

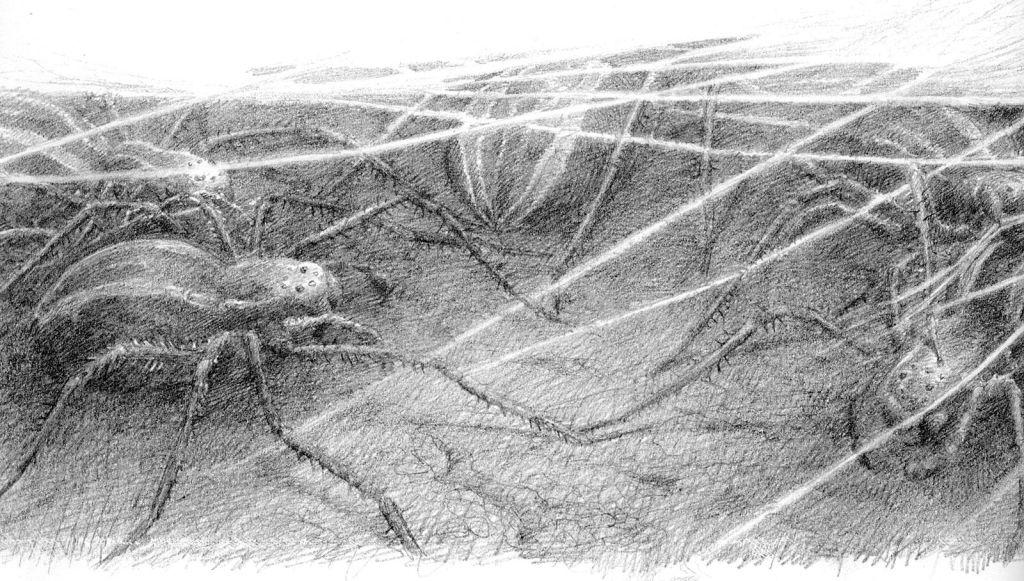

Well, we might begin by saying that he is only mentioned in Tolkien’s Hobbit, (Chapter 7, “Queer Lodgings”) and appears, but only briefly, as a messenger from Saruman in The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 2, “The Council of Elrond”.

He is one of the 5 Istari, sent to Middle-earth as a counter-balance to Sauron. (On the Istari, see Unfinished Tales, 405-412). It may be that Tolkien himself thought that he had become a little too acclimatized:

“Indeed, of all the Istari, one only remained faithful, and he was the last-comer. For Radagast, the fourth, became enamoured of the many beasts and birds that dwelt in Middle-earth, and forsook Elves and Men, and spent his days among the wild creatures.” (JRR Tolkien, The Lost Tales, 407)

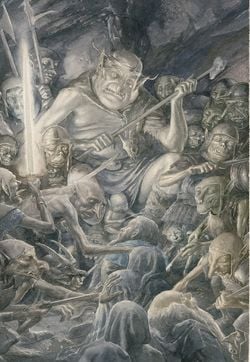

But this doesn’t mean that he’s become what Saruman sneeringly calls him: “Radagast the Bird-tamer! Radagast the Simple! Radagast the fool!” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 2, “The Council of Elrond”)—although he could easily be taken for that in Jackson’s Hobbit, for all that he’s had invented for him a role that seems to want to combine the clownish with the heroic, but, for me, as JRRT did not create this role and would certainly have been upset by the clownish aspects of it–

see his comment on illustrations for a German translation of The Hobbit sent him by Horus Engels:

“He has sent me some illustrations (of the Trolls and Gollum) which despite certain merits, such as one would expect of a German, are I fear too ‘Disnified’ for my taste: Bilbo with a dribbling nose, and Gandalf as a figure of vulgar fun rather than the Odinic wanderer that I think of…” (letter to Sir Stanley Unwin, 7 December, 1946, Letters 171-172)

he seems not only unnecessary, but exactly what disturbed Tolkien about the Zimmerman “treatment” of The Lord of the Rings, the reaction of an author who finds:

“…increasingly as he proceeds, his work treated as it would seem carelessly , in places recklessly, and with no evident signs of any appreciation of what it is all about…”

Hence the title of this posting—not the fear generated by the Old English gaest , of the original word, but certainly a sense of disturbance of the sort JRRT felt in that “treatment” and I’m sure would have felt even more strongly seeing what had happened to his character in the hands of those who, at best, are reckless.

Thanks, as always, for reading,

Stay well,

Believe that the author means what she/he says,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

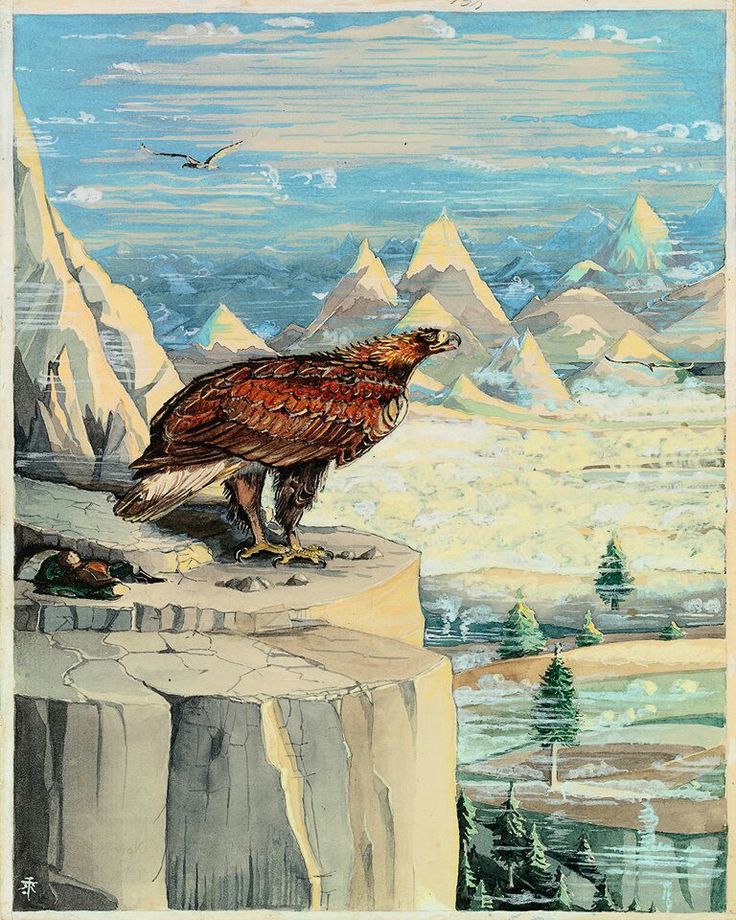

For me, this illustration, by Lucas Graciano, seems a better depiction—

(you can see more of his imaginative art here: https://www.lucasgraciano.com/ )