Tags

As always, welcome, dear readers.

Occasionally, I return to something I’ve already written about, but, this time around, hope to see in a new, or at least newish, light. The subject of today’s posting first appeared back in “Do What I Say, Not What I Speak”, 13 June, 2018, but, since then, I began my campaign to read all of The Arabian Nights and am now in the second volume of the Penguin edition (for the first volume, see “Arabian Nights for Days”, 31 January, 2024).

I’ve known some of the stories in this vast collection since childhood, but the first two stories I heard as a child are actually so-called “orphan tales”, being stories which appear to have no early manuscript tradition, first appearing in Antoine Galland’s (1646-1715)

Les Mille et Une Nuits (1704-1717).

and from there into the first edition in English, the anonymous so-called “Grub Street Edition” of 1706-1721.

(This is an image from the earliest edition I can locate—as you can see, it’s from 1781. Only two copies of the first edition are known to exist, one in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, the other in the rare books collection of Princeton University and clearly they don’t get out much.)

There has been much discussion as to the actual origins of “Aladdin”

and “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves”–

in particular, that, although they contain standard folktale motifs, they are actually the work of a Syrian storyteller named Antun Yusuf Hanna Diyab (c.1668-post-1763) and were added by Galland to his translation without attribution. (For more, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanna_Diyab )

Whatever is the truth of this, these were the stories I carried in my head for years before I came back to them when commencing my “Arabian Nights” reading campaign.

When I was small, they were actually quite scary—the magician who pretends to be Aladdin’s long-lost uncle and who only wants to use him long enough to obtain the lamp, then would let him die in the cave where the lamp was kept, and the merciless thieves, who once they found their cave with its secret password was compromised, cut up Ali Baba’s brother who had discovered the secret but, who, forgetting the password, was trapped until the thieves returned, were among the creepier parts of my childhood, and, as may always be the case with creepy things, not easily forgotten.

At the same time, I was always puzzled by the opening to “Ali Baba”:

“IN a town in Persia there dwelt two brothers, one named Cassim,

the other Ali Baba. Cassim was married to a rich wife and lived

in plenty, while Ali Baba had to maintain his wife and children by

cutting wood in a neighbouring forest and selling it in the town.

One day, when Ali Baba was in the forest, he saw a troop of men

on horseback, coming towards him in a cloud of dust. He was

afraid they were robbers, and climbed into a tree for safety. When

they came up to him and dismounted, he counted forty of them.

They unbridled their horses and tied them to trees. The finest man

among them, whom Ali Baba took to be their captain, went a little

way among some bushes, and said: ‘ Open, Sesame!’ so plainly that

Ali Baba heard him. A door opened in the rocks, and having made

the troop go in, he followed them, and the door shut again of itself.”

Why would a door obey a password? And why that word, which I knew was a kind of seed.

(For more—much more—see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sesame#Allergy )

This sat somewhere in my memory until I read:

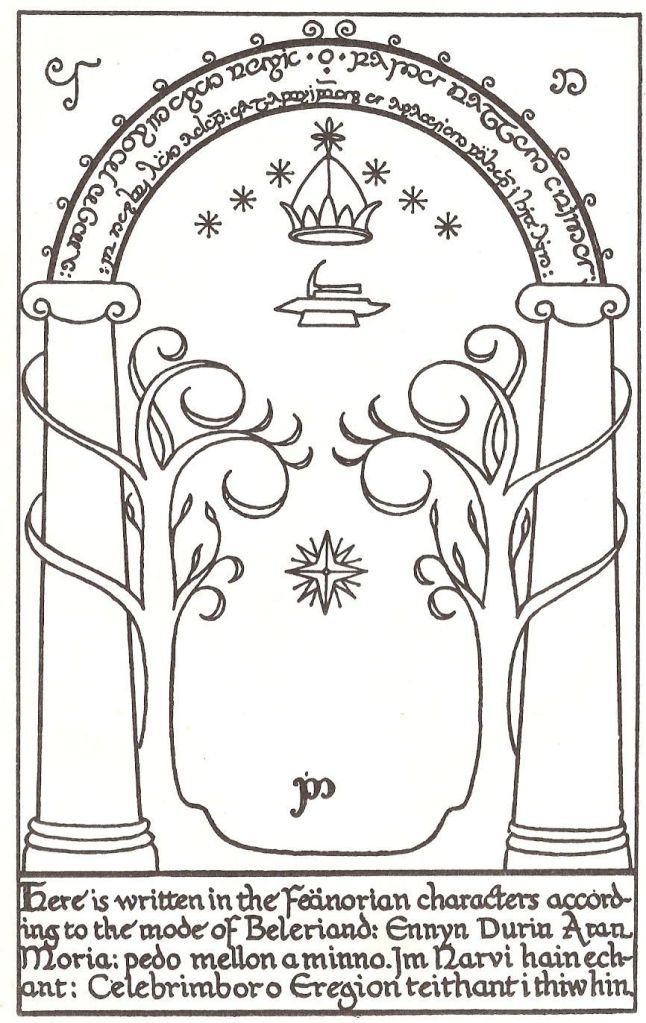

“But close under the cliff there stood, still strong and living, two tall trees, larger than any trees of holly that Frodo had ever seen or imagined…

(JRRT)

‘Well, here we are at last!’ said Gandalf. ‘Here the Elven-way from Hollin ended. Holly was the token of the people of that land, and they planted it here to mark the end of their domain; for the West-door was made chiefly for their use in their traffic with the Lords of Moria.’ …

…they turned to watch Gandalf. He appeared to have done nothing. He was standing between the two trees gazing at the blank wall of the cliff, as if he would bore a hole into it…

‘Dwarf-doors are not made to be seen when shut,’ said Gimli. ‘They are invisible, and their own makers cannot find them or open them, if their secret is forgotten.’

‘But this Door was not made to be a secret known only to Dwarves,’ said Gandalf…’Unless things are altogether changed, eyes that know what to look for may discover the signs.’

He walked forward to the wall. Right between the shadow of the trees there was a smooth space, and over this he passed his hands to and fro, muttering words under his breath. Then he stepped back.

‘Look!’ he said. ‘Can you see anything now?’

…Then slowly on the surface, where the wizard’s hands had passed, faint lines appeared, like slender veins of silver running in the stone…

At the top, as high as Gandalf could reach, was an arch of interlacing letters of an Elvish character.

(Ted Nasmith)

Below, though the threads were in places blurred or broken, the outline could be seen…

(JRRT)

‘What does the writing say?’ asked Frodo…

‘…They say only: The Doors of Durin, Lord of Moria. Speak, friend, and enter.’

‘What does it mean…?’ asked Merry.

‘That is plain enough,’ said Gimli. ‘If you are a friend, speak the password, and the doors will open, and you can enter.’ “ (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 4, “A Journey in the Dark”)

We know from various clues, like the story title “Storia Moria Castle”, that Tolkien had read—or been read to—from Andrew Lang’s (1844-1912) The Red Fairy Book, 1890,

but, interestingly, “Aladdin” and “Ali Baba” both appear in Lang’s previous The Blue Fairy Book, 1889,

from which both the “Ali Baba” quotation and illustration above, come. Could Tolkien have been read to from, or read, “Ali Baba” there? Certainly we see that door, and the need for the password. But what about that password?

In The Fellowship of the Ring, Gandalf tells us that “ ‘I will tell you that these doors open outwards. From the inside you may thrust them open with your hands. From the outside nothing will move them save the spell of command. They cannot be forced inwards.’ Try as he might, however, Gandalf can’t come up with that word—until he realizes that he’s made a slight mistranslation:

“ ‘The opening word was inscribed on the archway all the time! The translation should have been Say “Friend’ and enter. I had only to speak the Elvish word for friend and the doors opened.’ “

To a linguist with a fine ear, like JRRT’s, the distinction, in English, between the verb “to speak”, as in “to speak a language”, and “to say”, as in “to say the right thing”, can be subtle—in this case, almost too subtle—as Gandalf says:

“ ‘Quite simple. Too simple for a learned lore-master in these suspicious days.’ “

With the problem solved, the doors swing open—but where they’re about to go is, ultimately, worse than Ali Baba’s thieves’ treasure cave, even as I’m reminded of what happens to Ali Baba’s jealous brother. Obtaining the password, he easily enters the cave, but, when he tries to leave, he confuses “sesame” with other grains, is trapped, and eventually dismembered by the returning thieves. (Think Balrog and “Drums in the Dark”…)

And, though “Friend”, says Gandalf, is quite simple, and, adding, “Those were happier times” in which such a pleasant password was all that was necessary, I’m still puzzled about “sesame” and, in both cases, I wonder about those doors—who or what was doing the opening? Then again, when I post this, I’ll need a password and, when I employ it, the site will pop open—who or what is doing the opening there?

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

When it comes to locks, I prefer a good, sturdy key,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

In case you want to read the two fairy books—and I hope you do—here they are:

The Blue Fairy Book

https://archive.org/details/bluefairybook00langiala/page/n7/mode/2up

The Red Fairy Book

https://archive.org/details/cu31924084424013/page/n9/mode/2up