Tags

Black Death, Black Plague, black ship rat, flea, Great Fire of London, great-london-fire, Halloween, History, miasma, plague, plague doctor, plague pits, Roger Bacon, Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare, Trick or Treat, Yersinia Pestis

As always, dear readers, welcome.

It’s almost Halloween again, one of my favorite holidays, when children dress up in various costumes and wander the streets in groups, demanding treats and threatening tricks,

while older people, themselves in costume, attend parties.

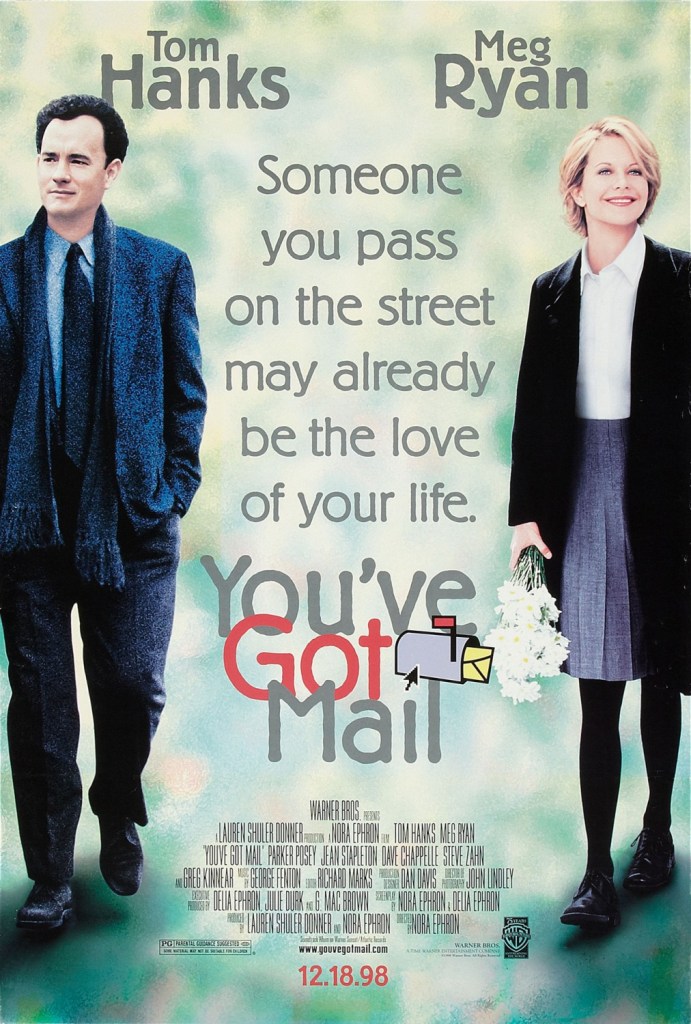

People dress up as monsters, vampires, and superheroes, but, recently, I’ve also seen a few of these—

a costume which you can actually buy on Amazon.

It’s a very haunting image: crowlike, and yet not, and it struck me as an interesting basis for this year’s Halloween posting.

But what is it?

If you don’t know, I’ve given you a clue in that (modified) quotation I’ve used as a title.

In Act III, Scene 1, of Shakespeare’s The Most Excellent and Lamentable Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet, 1591/95, as the 2nd Quarto (1599) has it,

Romeo’s best friend and perhaps the sanest character in the play, Mercutio, has been mortally wounded. Dying, he curses both of the feuding families, wishing that a plague would take them both.

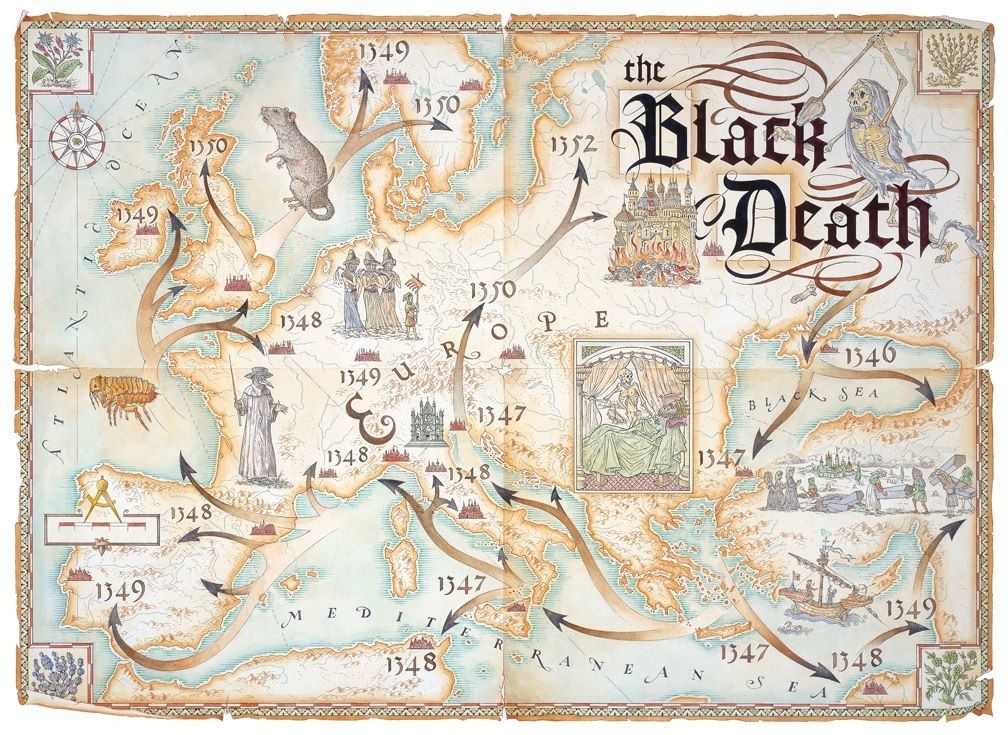

In Shakespeare’s England, this was not a random remark. Since its original appearance, in 1348, when it may have killed as many as 40-60% of the population, the Black Plague (aka the Black Death) had

reappeared over the next couple of centuries, killing 30,000 in London, in 1603 alone,

before its grand finale (or nearly), in 1665-6,when it was responsible for perhaps 100,000 deaths there.

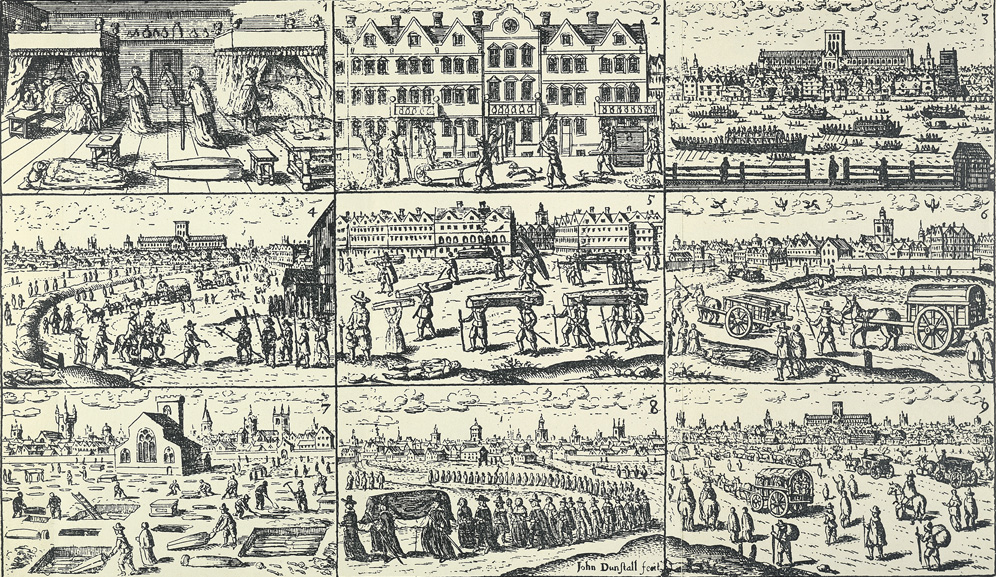

(And, in 1666, came the great fire, which destroyed much of the city—it’s a wonder that everyone surviving didn’t attempt to flee to anywhere as far away as they could.

For the fire, I recommend J. Draper’s short presentation here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4bvB_gJThYk with one correction. She says that the artist/engraver Wenceslaus Hollar was Dutch when, in fact, he was a Czech. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wenceslaus_Hollar Otherwise, I have nothing but praise for Draper, who does proper research and wanders the London area , looking for odd and interesting aspects of London’s—and English—history which she then presents in creative ways. For her grim and striking view of the Black Death, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ybh1jSZLIKY )

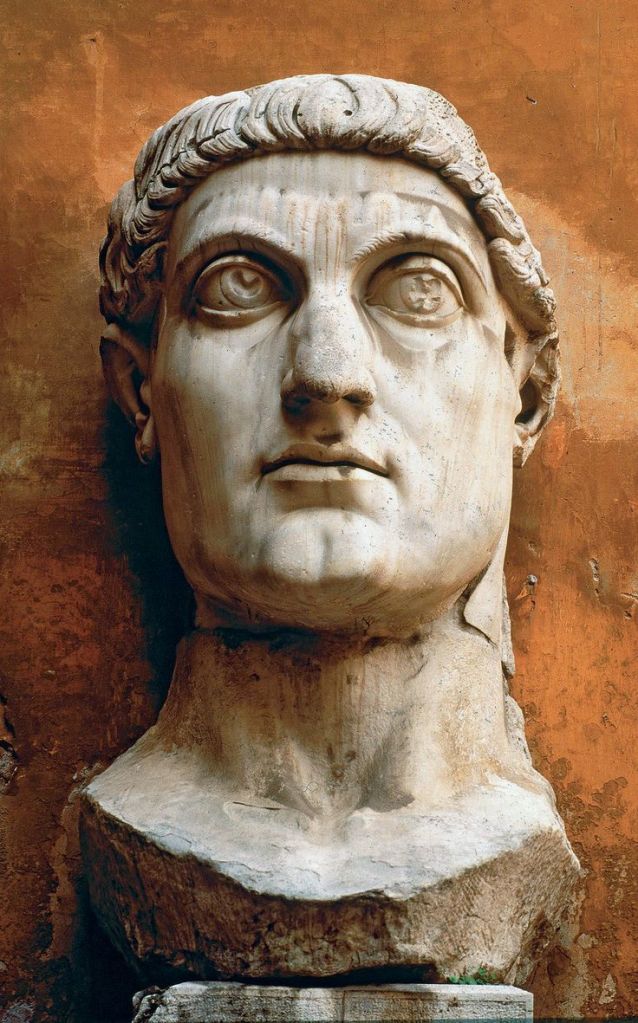

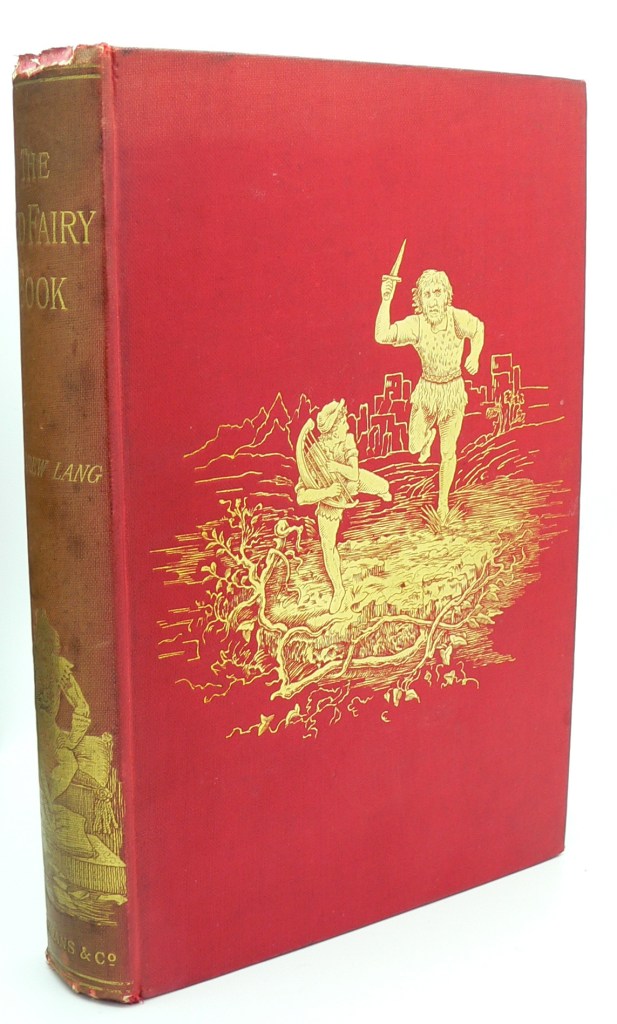

Medieval science was not really even in its infancy—although there were highly intelligent and thoughtful men struggling to look at the world without superstition or religion, like Friar Roger Bacon, 1214-1294.

(an imaginary image—we have no known portrait)

Medical science, such as existed, followed the classical world and believed that communicable diseases were spread through miasma—that is, through “bad air”,

which isn’t such a far-fetched idea: rotting things, dead things, stink, so death and bad smells are easily associated.

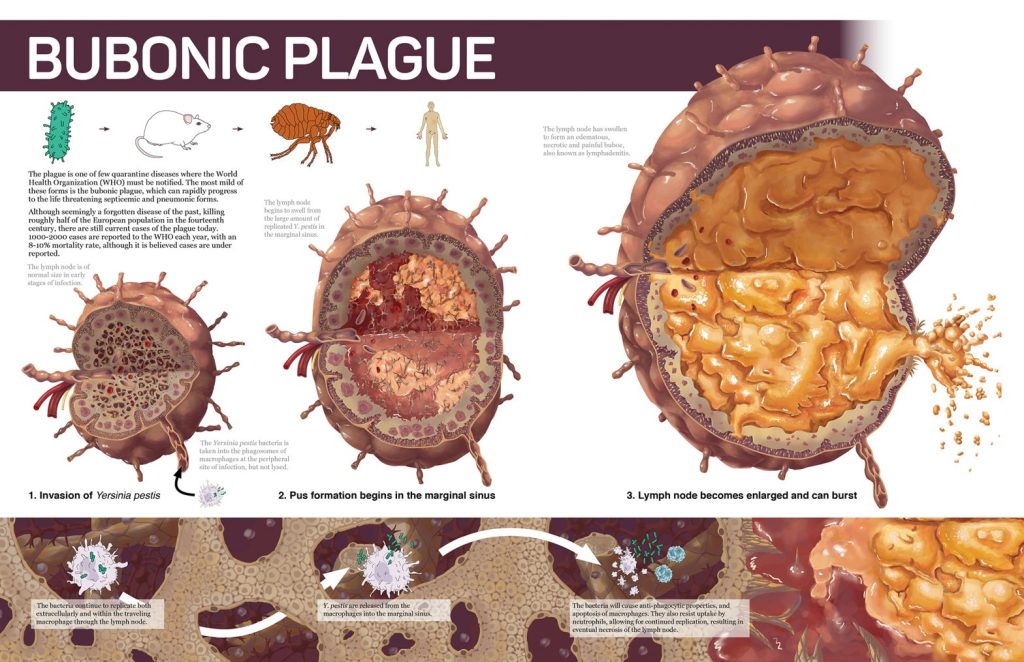

In fact, the Black Plague was—and is–a bacterium, Yersinia Pestis,

which lives in the gut of fleas,

which inhabited what was called the “black ship rat”,

which traveled on trading vessels from the Far East in the 14th century,

and eventually came, either directly on rats, or indirectly by a human carrier, to England, causing havoc on and off, for several centuries.

Needless to say, in a packed city, like London,

rats and their passengers could easily spread out and, in doing so, would spread the bacterium through the bites of those fleas.

Medical men of that world, however, could make no such connections. They only saw the horrible symptoms—including the swelling of the lymph nodes, attempting to defend the body—the buboes of bubonic plague—

(This is such a gross image that I almost didn’t include it, but it’s very helpful in explaining what exactly was going on in the body, so…)

The plague produced fever, chills, vomiting, violent headaches—and all that doctors could do was what they did for almost anything: try to balance the humors—the basic elements of the body—which included bleeding, a treatment which actually weakened the body.

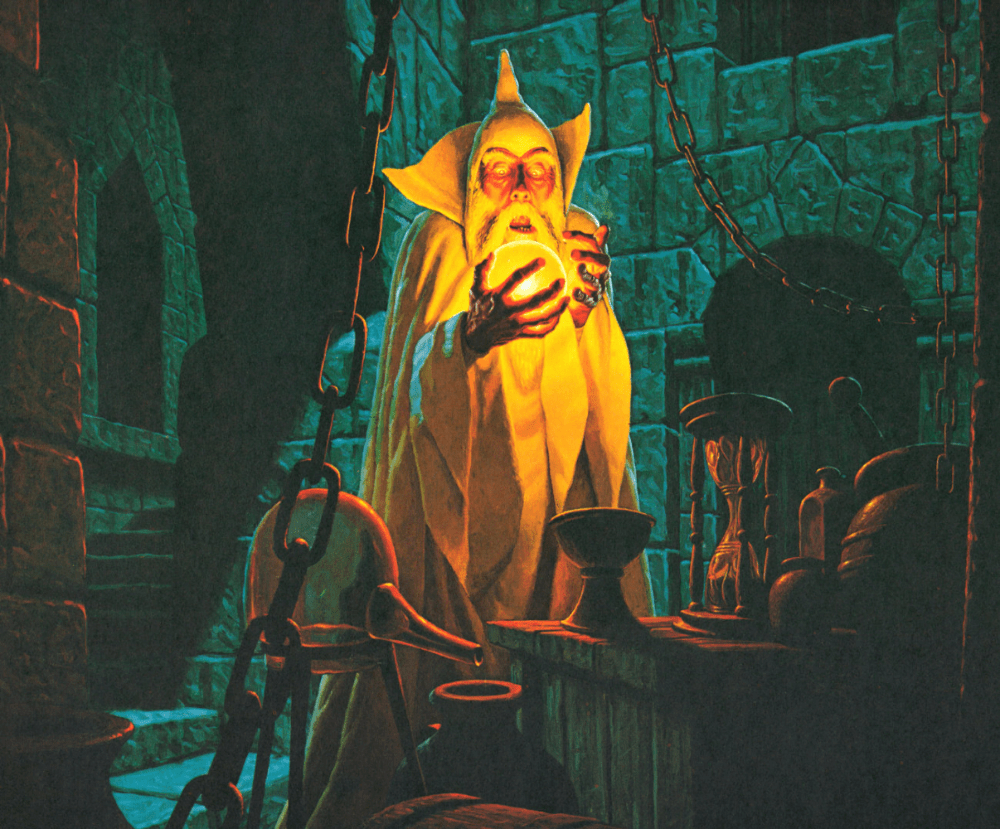

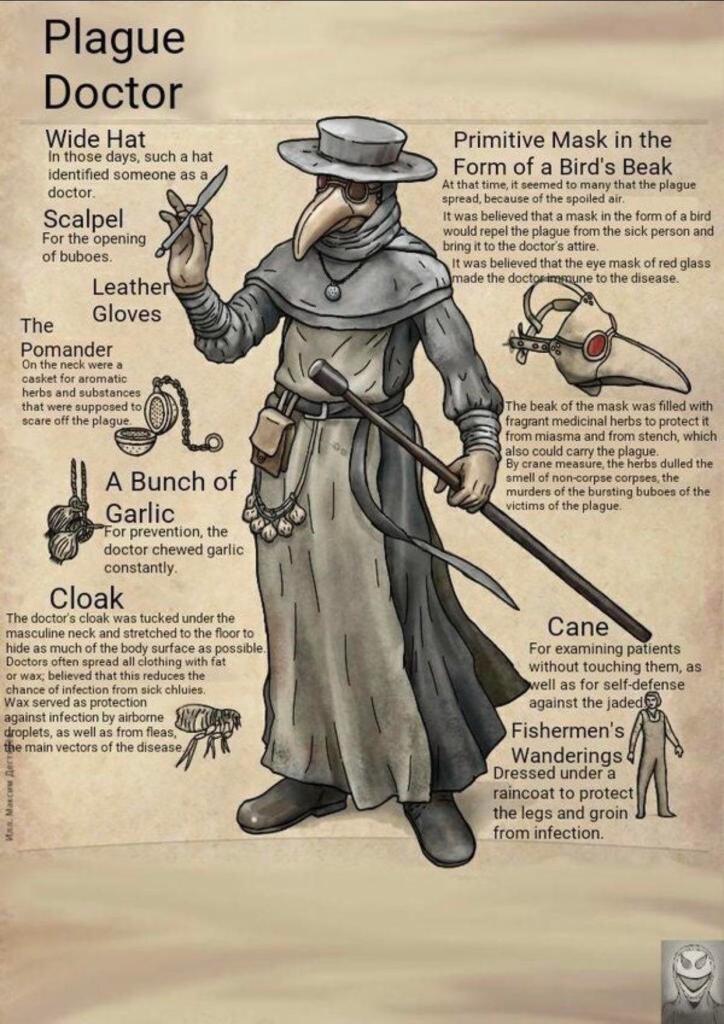

Because the real agent of contagion wasn’t understood, doctors could only be brave and deal with their patients as best they could—and contract the disease themselves—or could attempt to protect themselves, which brings us to this image again—

(appropriately titled “the clothing against death”, implying the Black Death)

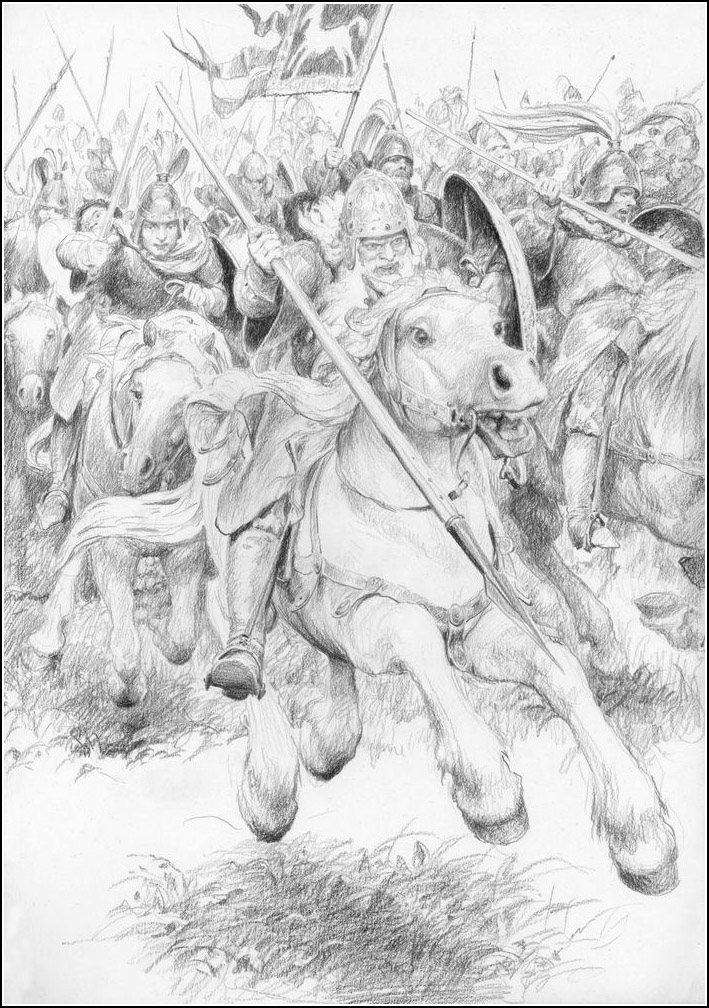

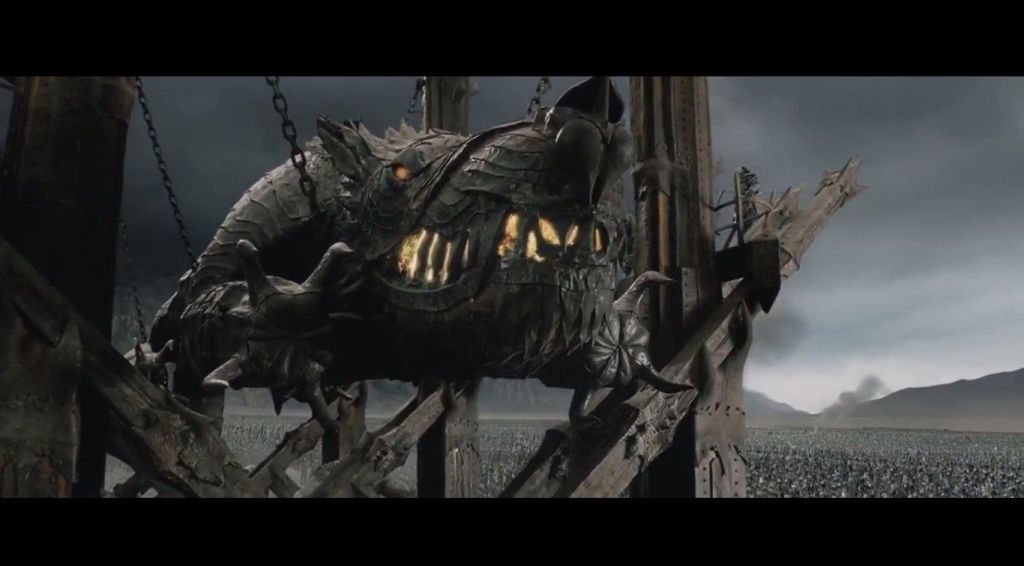

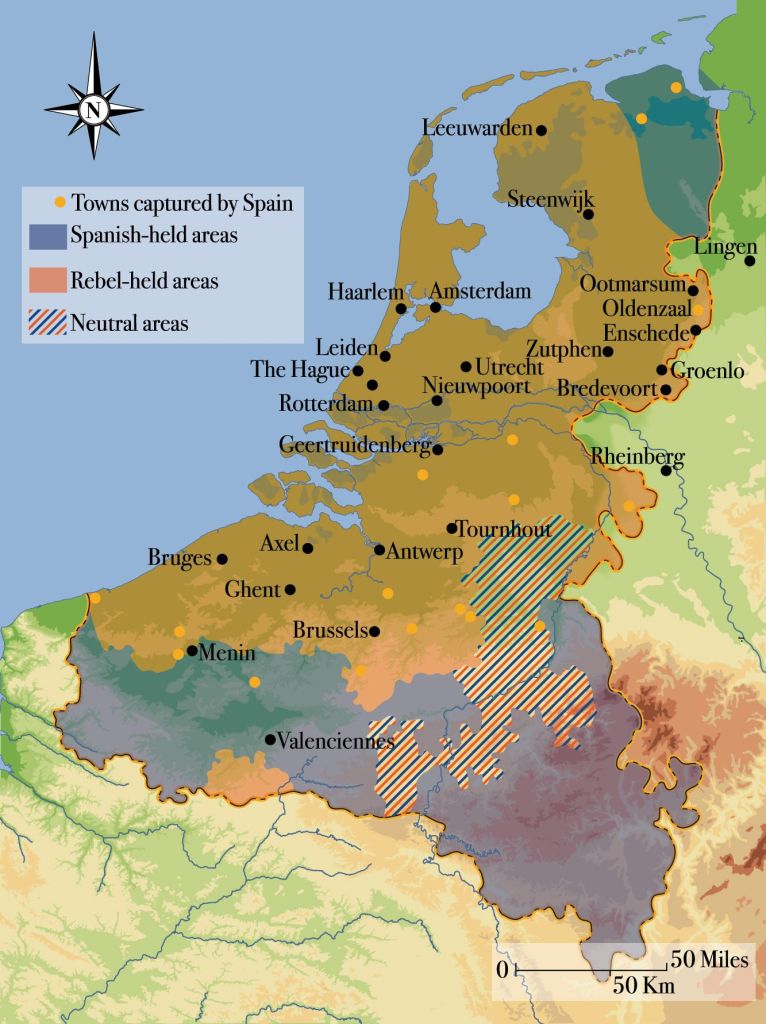

This diagram

(with some strange English—it appears to be a translation—I’ve seen one copy in which the text is in Russian– gives you a general idea of how a doctor might attempt to ward off infection, including basics which had to do with bad air, like carrying a pomander—a little vessel containing strong-smelling herbs to fend off that air—

which someone might carry simply to ward off the bad smells of a time when streets in cities often had the equivalent of open sewers, as well as might be employ ed as a fashion accessory—for more on pomanders, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pomander )

as well as that beaky thing—which is really a kind of early surgical mask

combined with a pomander—the beak being stuffed with those protective herbs. And, as who knows what can get in through the eyes, add crystalline lenses to the beak.

Gloves and a long coat, sometimes waxed, probably as much for water-proofing as against floating miasma, and a broad-brimmed hat to cover the head, complete the outfit. Oh—and a rod for probing the infected, plus a light source—medieval/Renaissance houses being notoriously dim.

Note, however, that, whoever designed this modern version hadn’t done quite enough research: that’s a 19th-century kerosene lantern. Here’s a lantern of a sort which would be likely—

(This is an Elizabethan image of a city watchman, armed with a spear, followed by a dog, and carrying a bell to sound the hours.)

And so, when you see someone dressed like this at a party, you can confidently ask, “Tell me, doctor, is the plague spreading and should I flee the city?”

although he may respond by offering you not a pomander, but one of these, instead.

Thanks, as always for reading. Happy Halloween, if you celebrate it.

Stay well,

Avoid miasma like the plague,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

There is now some argument about the gear of such doctors. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plague_doctor and https://www.livescience.com/plague-doctors.html Plague could actually take several forms. See: https://www.britannica.com/science/plague Because cemeteries—and grave-diggers were often overwhelmed, mass graves in unconsecrated ground began to be common—and now are sometimes happened upon unexpectedly. See recent London plague pit discoveries: https://www.cityam.com/after-crossrails-gruesome-discovery-weve-mapped-every-one-londons-plague-pits-do-you-work/