Tags

Alfred Tennyson, Austrian, Balaclava, British Cavalry, chasseurs a cheval, Crimean War, Errol Flynn, Flashman, French, Gallic, gendarmes, George Macdonald Fraser, Heavy Brigade, Hungarian, Hussars, jinetes, lancers, Light Brigade, Light Dragoons, Napoleonic, North Africans, Olivia deHavilland, Renaissance cavalry, Romans, Russian Artillery, Spanish, St Helena, The Charge of the Light Brigade, Thomas Hughes, Tom Brown's School Days

As ever, dear readers, welcome.

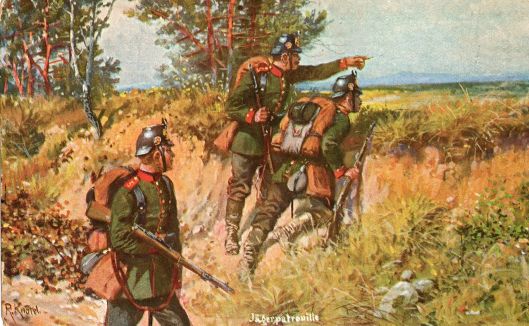

Recently, someone asked us about the Light Brigade—that is, the collection of regiments of British cavalry who fought in the Crimean War (1854-56).

These are the troopers who mistakenly charged Russian artillery in the series of battles fought on 25 October, 1854, called, collectively, Balaclava.

The question was, “Why was it called ‘the Light Brigade’? Were the soldiers thin? And was there a Heavy Brigade, where they were all fat?”

It seemed to us a very reasonable question and our answer began, “Over many centuries, cavalry has had a number of uses, but they could probably be broken down into two groups by those uses: 1. raids, skirmishes, scouting, and pursuit; 2. attacking enemy cavalry and infantry formations—and pursuit. The former (#1) is the job of light cavalry, the latter (#2) of heavy cavalry.”

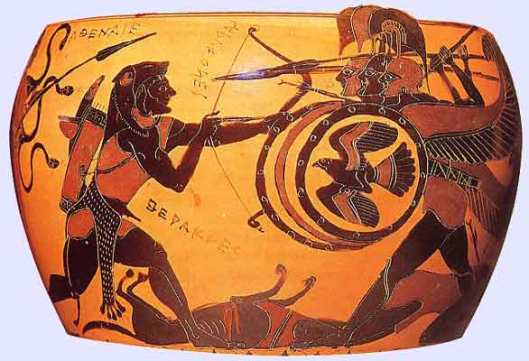

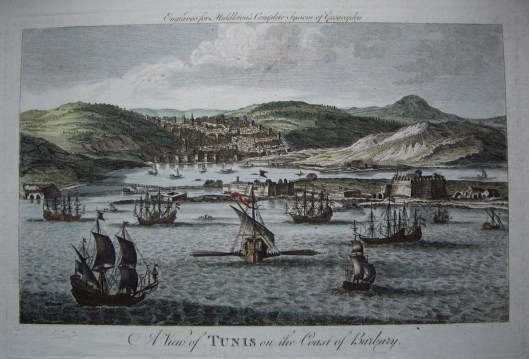

The Romans, who themselves only produced cavalry early in their history, quickly preferring to hire the job out, might, for example, use North Africans as light cavalry.

If heavy cavalry were needed, then the task might go to Spanish or Gallic soldiers.

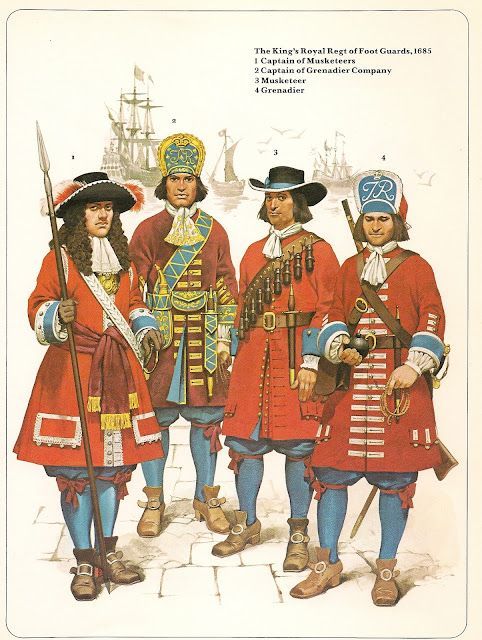

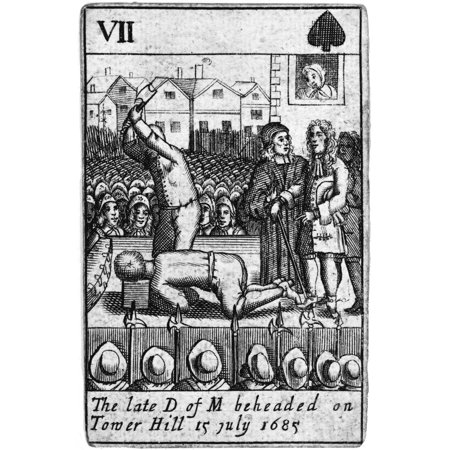

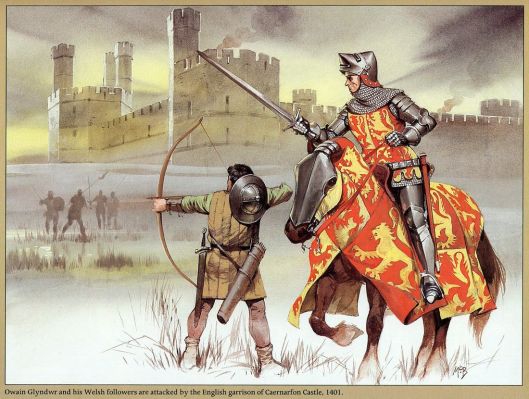

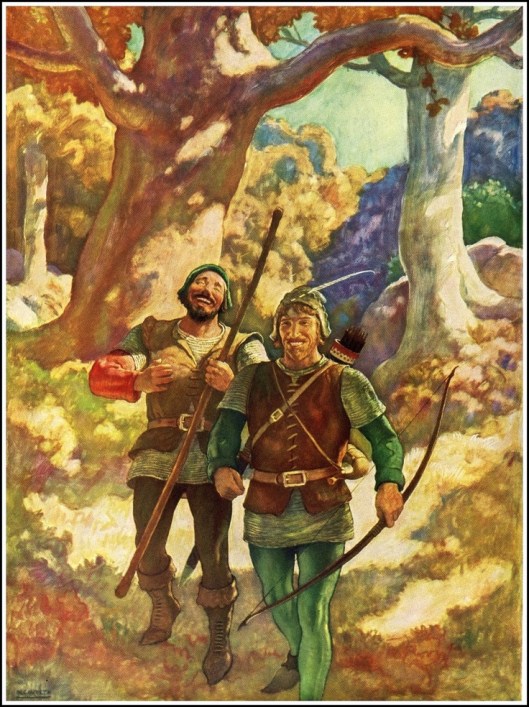

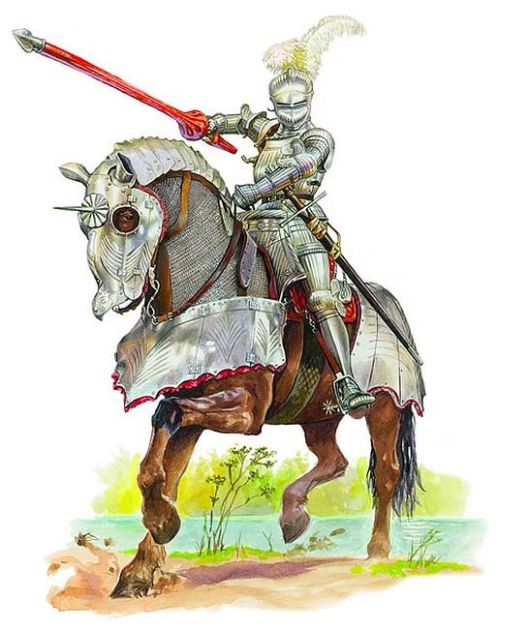

And this would be true throughout military history—Renaissance cavalry might have heavily-armored gendarmes

to break up an enemy unit (or more) with the weight of its charge, but would also use lightly-armed jinetes

to find out the enemy’s positions, or attack their supply routes.

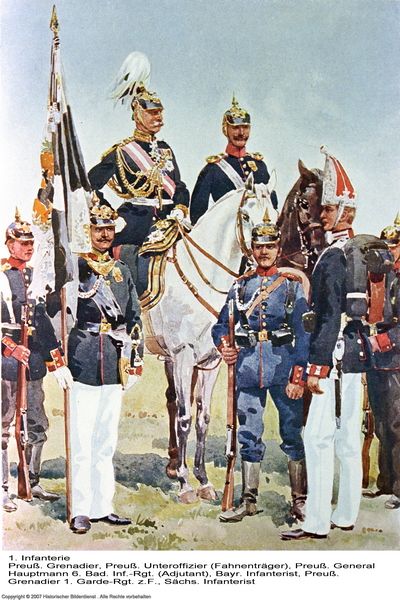

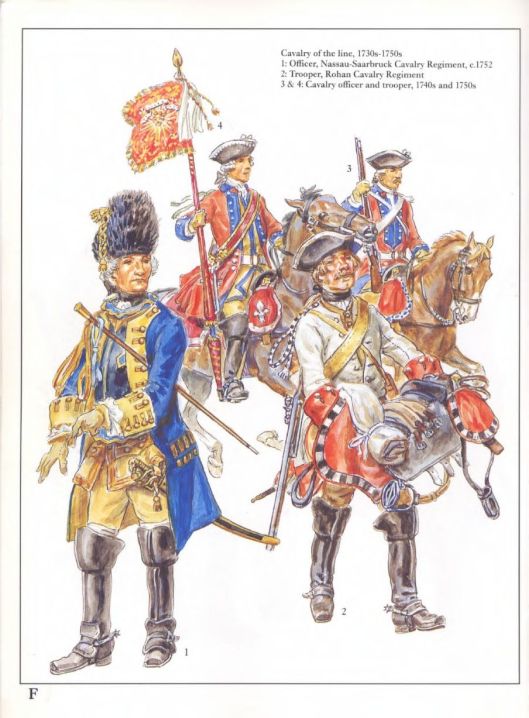

In the 18th century, most cavalry were heavy—although armor had almost disappeared.

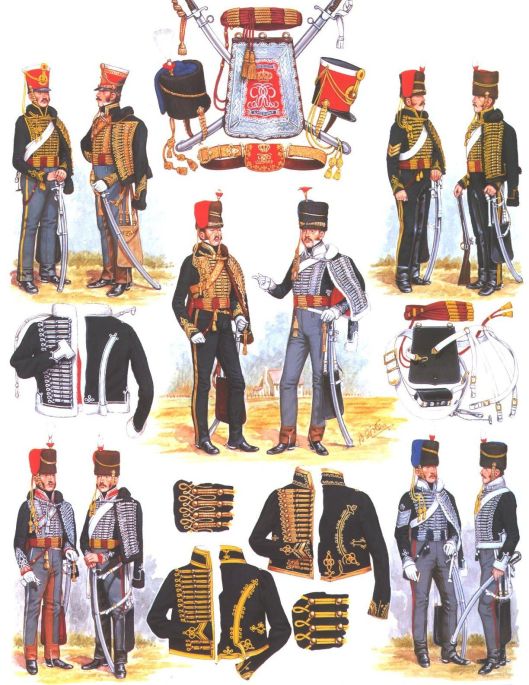

The Austrians and then the French added to those heavies light cavalry originally from the Hungarian world, hussars.

Not to be outdone, the English fleshed out their heavy cavalry

not with hussars, but something they called “light dragoons”.

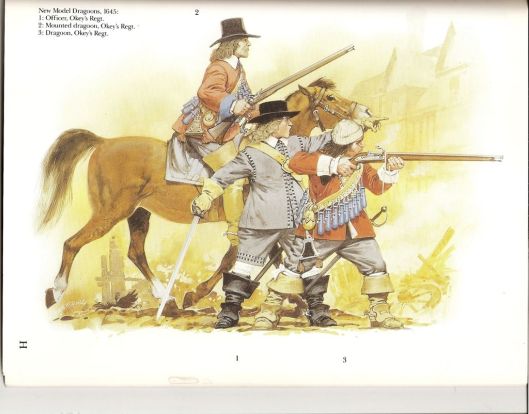

Dragoons had originally been mounted infantrymen, who rode to battle on horseback, then dismounted to fight,

but, by the mid-18th century, dragoons were just heavy cavalry—bigger men on bigger horses—and light dragoons were smaller men on smaller horses, with mostly different functions.

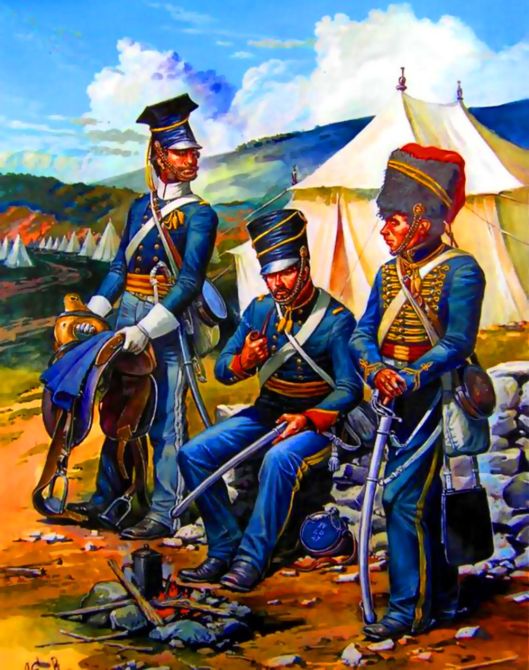

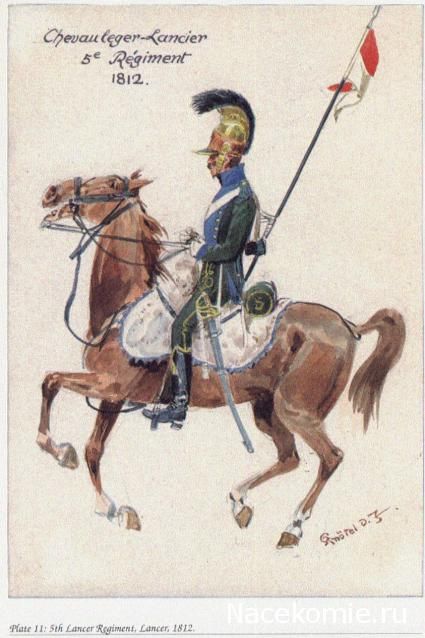

By the end of the century and just beyond, during the Napoleonic era, the French, in particular, had developed a whole series of light cavalry types—hussars,

chasseurs a cheval (literally, “hunters on horseback”),

and lancers, as well.

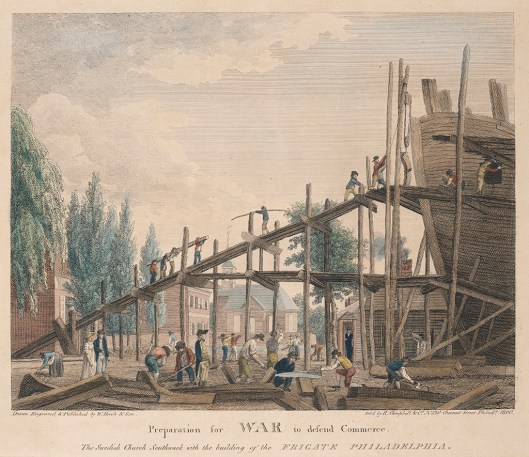

The English, to match the French, converted some regiments to hussars,

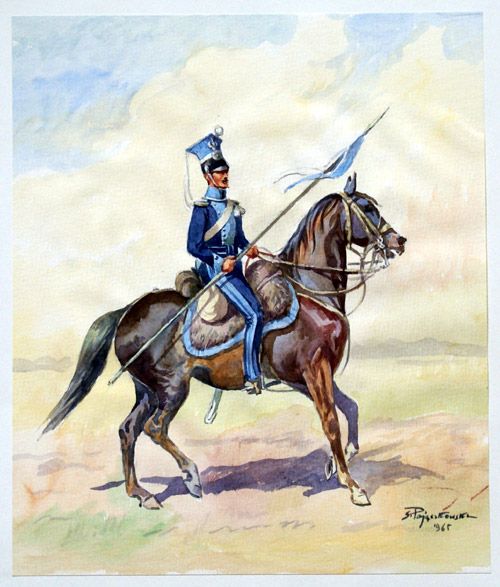

but only after 1820, when Napoleon was in his second and final exile on St. Helena, did they convert several other regiments to lancers.

(You can see that they borrowed their style of dress from that of Polish lancers in Napoleon’s armies.)

These lancers

along with hussars

and light dragoons

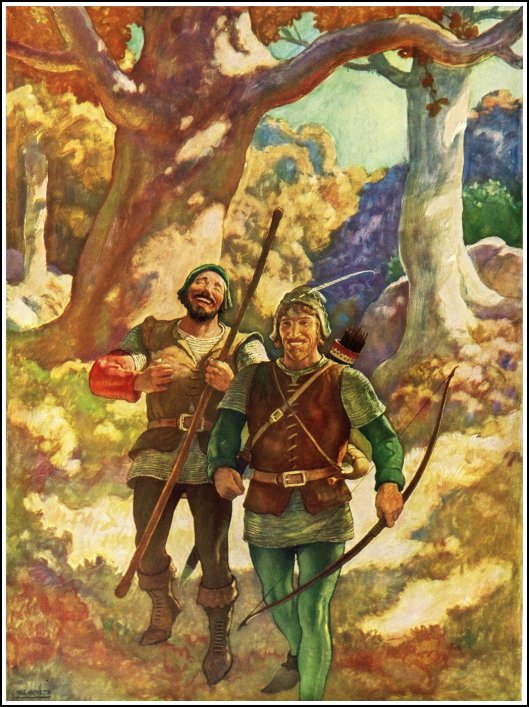

made up the famous Light Brigade of Alfred Tennyson’s (1809-1892)

1854 poem, “The Charge of the Light Brigade”.

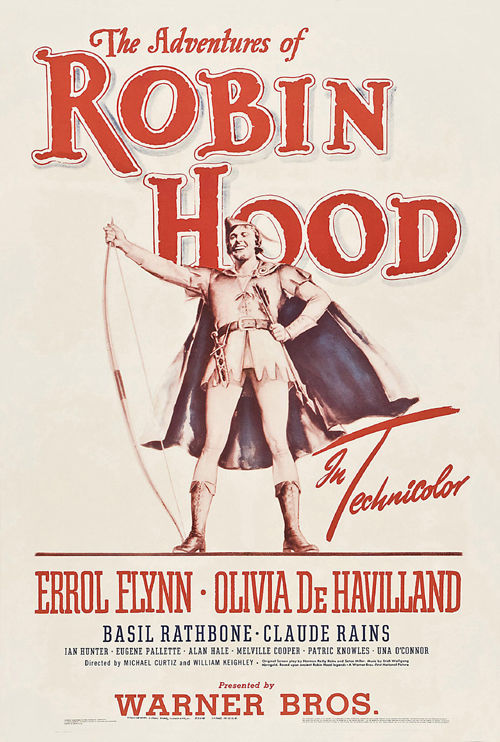

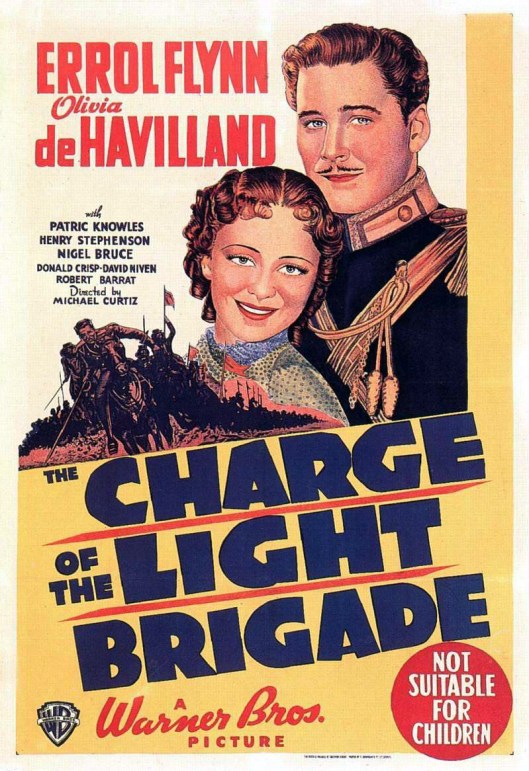

This, in turn, inspired one of our favorite adventure movies, the 1936 The Charge of the Light Brigade.

(We wonder how different children must have been in 1936—we loved that movie as kids!)

And this film, in turn, inspired a 20th-century adventure writer, George Macdonald Fraser (1925-2008),

who wrote a series of 12 books detailing the life of one Harry Flashman, beginning with Flashman (1969).

In part, these are a parody of the life of a typical Victorian officer, who eventually becomes General Sir Harry Flashman. He appears at many of the famous military events in mid-Victorian British history, from the First Afghan War (1839-1842) to the Zulu War (1879), along with appearances at later events, including a cameo appearance at the British declaration of war against Germany on 4 August, 1914. The joke is, although he wins all sorts of honors, including that knighthood, he is, in fact, a complete coward and it’s only amazing luck that he manages to survive as long and as well as he does. And there is a second joke within the first: Flashman is actually the school bully in a very famous earlier novel, Tom Brown’s School Days (1857),

by Thomas Hughes (1822-1896), a book which is the ancestor not only of many later such novels and short stories, but also of the Harry Potter books.

The fourth novel in the Flashman series, entitled Flashman at the Charge (1973),

gives us Fraser’s hero as actually leading that famous attack by accident, an accident which leads to his capture by the Russians—and many further adventures.

So, our answer to the original question is: “No. The Light Brigade wasn’t skinny, but was called that because it was smaller men on smaller horses with very specific jobs which required rapid movement and greater flexibility than heavy cavalry.”

And, with that answer, we say thank you for reading and

MTCIDC

CD

ps

There was, in fact, a Heavy Brigade,

who made their own equally-heroic, but more successful, attack on the same day as the more famous Light Brigade charge. Bigger men on bigger horses, they drove advancing Russian cavalry out of the Heavy Brigade camp.