As always, dear readers, welcome.

I’m always interested to try to imagine things which Tolkien may allude to, but goes into no more detail about—a kind of teaser, and, for me, a challenge: what can we reconstruct—and how?

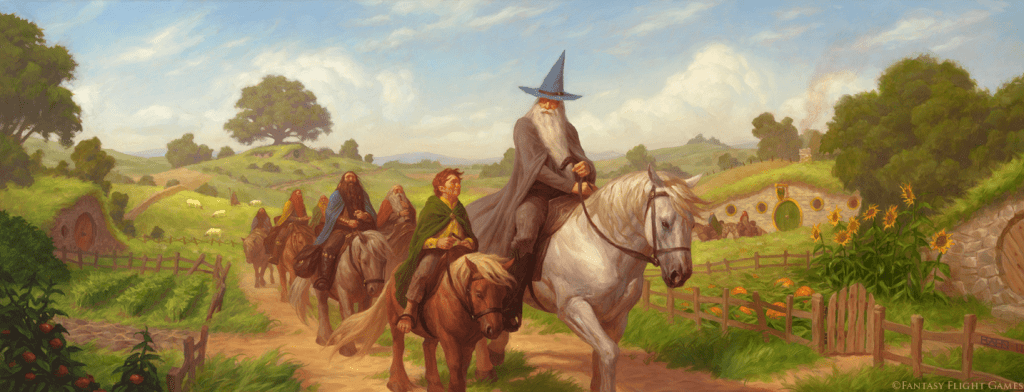

“About this time legend among the Hobbits first becomes history…They passed over the Bridge of Stonebows, that had been built in the days of the power of the North Kingdom, and they took all of the land beyond to dwell in, between the river and the Far Downs. All that was demanded of them was that they should keep the Great Bridge in repair, and all other bridges and roads, speed the king’s messengers, and acknowledge his lordship.” (The Lord of the Rings, Prologue I: “Concerning Hobbits”)

The “Bridge of the Strongbows” is the stone bridge which crosses the Baranduin/Brandywine on the road into the Shire from Bree, “bow” here meaning “arch”.

As far as I know, no artist has as yet depicted it, but I’ve always imagined it as looking rather like the Elvet Bridge, which spans the River Wear in the middle of Durham, England.

This was begun in 1160AD by the Norman bishop, Hugh de Puiset (c.1125-1195—a very interesting figure in the early centuries of Norman domination—you can read about him here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugh_de_Puiset and read more about the bridge here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elvet_Bridge ), but only finished sometime in the following century, suggesting both the time-consuming nature of its construction, as well as the expense, something less visible, but always there in the medieval world—cathedrals could take centuries to build, and not only because they were large and complex.

So, as it took time and money to build the “Bridge of Strongbows”, it would have taken more time and money to keep it in repair, let alone “all other bridges and roads”.

And here we are in what Thomas Carlyle, 1795-1881, referred to as the “dismal science”: economics in Middle-earth. (Carlyle uses the term more than once, but the general citation is to his–originally published under a pseudonym–“ Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question”, which you can read here: https://cruel.org/econthought/texts/carlyle/carlodnq.html If you read this site regularly, you know that one of its pleasures for me is being able to recommend all sorts of books, articles, music, to my readers. In this case, however, I must say that, for once, I don’t recommend something—unless you are curious as to the horrific attitudes of some 19th-century intellectuals on the subject of race and bondage. As an historical artifact, then, it’s worth a glance, but as an example of bigotry, it’s appalling, and unworthy of a man with the mind and sensibilities to know better.)

Tolkien himself was well aware of economics. As he says in a letter to Naomi Mitchison:

“I am not incapable of economic thought; and I think as far as the ‘mortals’ go, Men, Hobbits, and Dwarfs, that the situations are so devised that economic likelihood is there and could be worked out…”

(letter to Naomi Mitchison, 25 September, 1954, Letters, 292)

Tolkien, however, adds something to his letter which makes his ideas a little clearer and adds a medieval touch:

“…Gondor has sufficient ‘townlands’ and fiefs with a good water and road approach to provide for its population…”

“Townlands”, as Tolkien used it, was a term employed in Ireland to indicate the holdings, by landlords, of multiple farms held by tenants, who paid rent to the landlords. “Fief” is the feudal term for land given to a vassal by an overlord in return for taxes and military support when required. In other words, these are economic units, in which those who work the land pay for that work with rent, in one form or another.

So let’s consider the Shire.

In that same letter, Tolkien says:

“The Shire is placed in a water and mountain situation and a distance from the sea and a latitude that would give it a natural fertility, quite apart from the stated fact that it was a well-tended region when they took it over (no doubt with a good deal of older arts and crafts).”

As far as we can see, there are neither “townlands” or “fiefs”, but there is a form of government—in fact, a rather confused form:

1. a Thain–from Old English “thegn”–a significant landholder, one step down from an “ealdorman” (it’s much more complicated—see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thegn for more) a hereditary position owned by the Took family, whose holder was “master of the Shire-moot, and captain of the Shire-muster and the Hobbitry-in arms”

2. the Mayor of Michel Delving (or of the Shire) “who was elected every seven years at the Free Fair on the White Downs at the Lithe, that is at Mid-summer” JRRT says that “as mayor almost his only duty was to preside at banquets given on the Shire-holidays”, but then, I think, contradicts himself somewhat, saying “But the offices of Postmaster and First Shirriff were attached to the mayoralty, so that he managed both the Messenger Service and the Watch. These were the only Shire-services, and the Messengers were the most numerous, and much the busier of the two.” The Shirriffs were only a dozen—three per quarter—“Farthings” of the Shire, but there were, at the time of The Lord of the Rings another, larger group, the “Bounders”, meaning border guards, presumably also under his command.

There’s a postal service, then, and a two-part police force, as well as the need for infrastructure maintenance, all of which require that which Tolkien understands, as he tells us, but does not go into: money in some form.

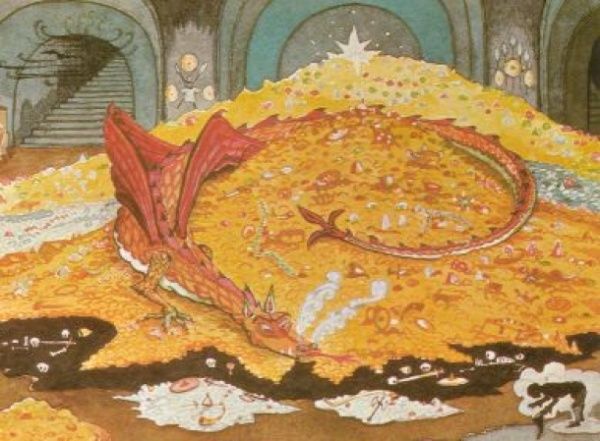

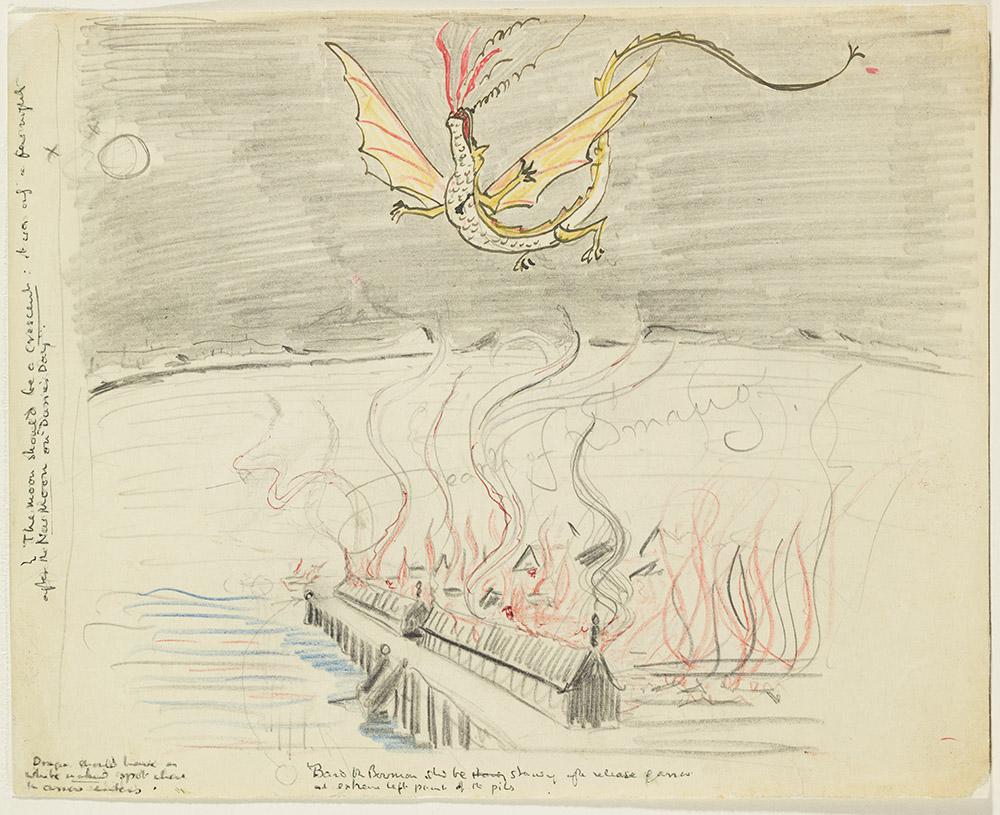

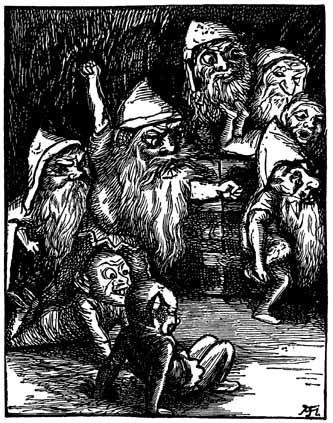

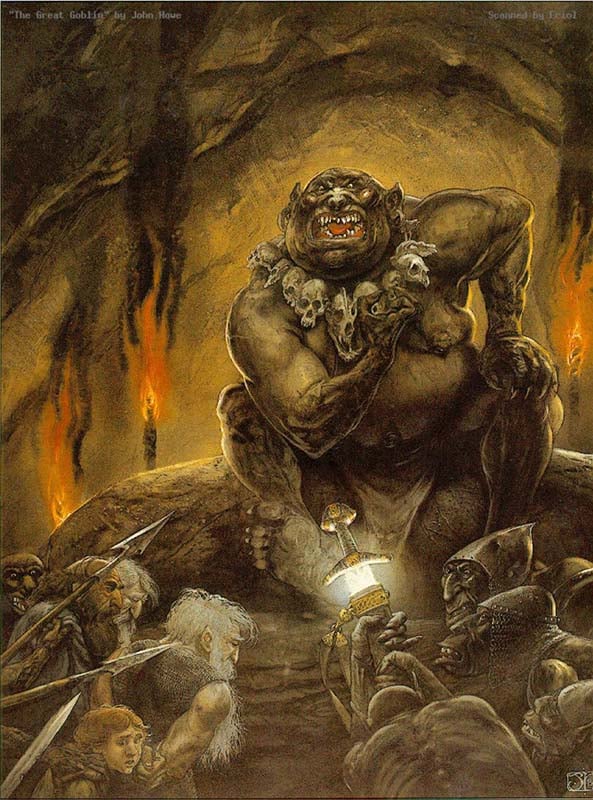

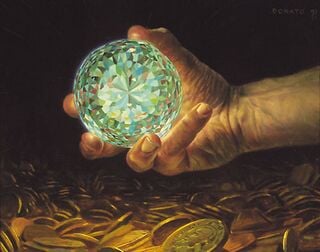

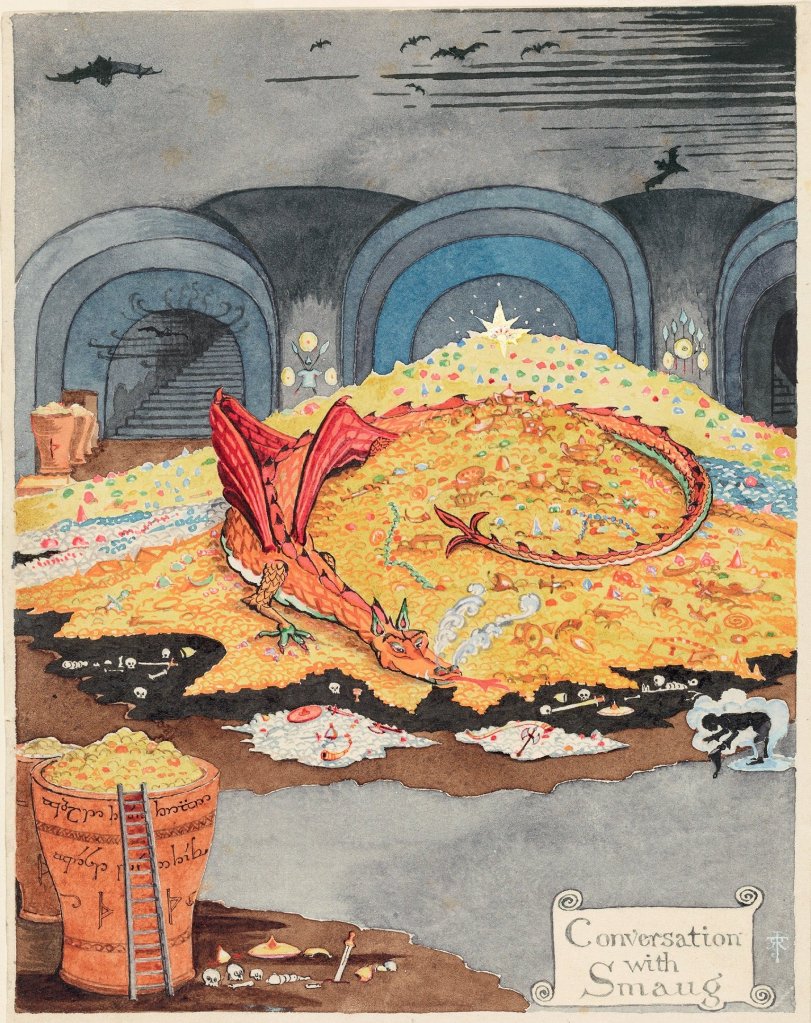

Money turns up in fantasy literature, but it only seems to belong to kings and people at the top, as well as in dragon hoards,

(JRRT)

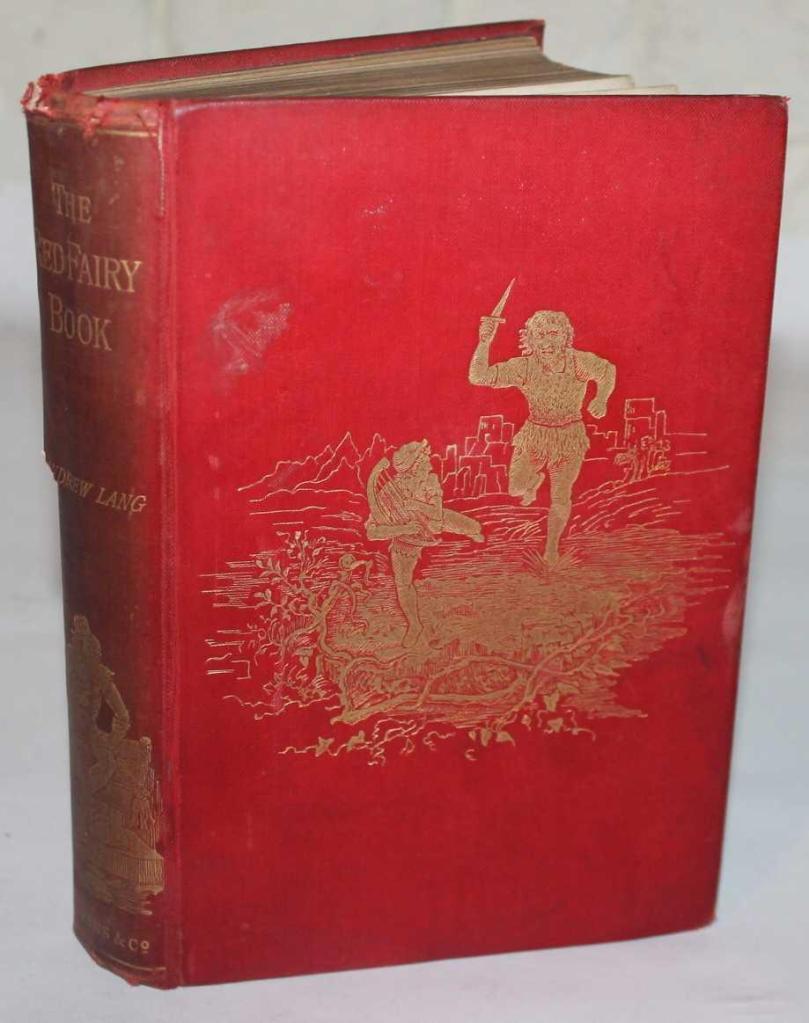

and in mysterious caches linked to beings like witches,

(Vladyslav Yerko—you can read about him here: https://www.artlex.com/artists/vladyslav-yerko/ and here: http://ababahalamaha.com.ua/en/Vladyslav_Yerko )

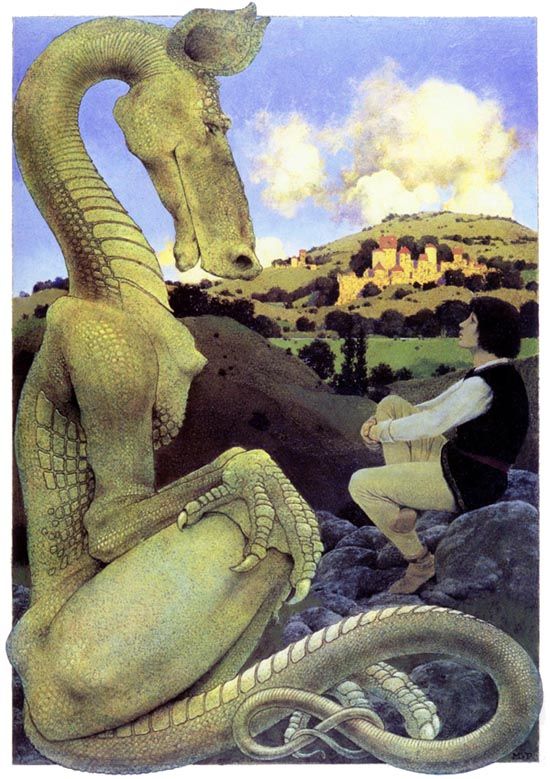

as well as in the hands of thieves.

Tolkien, just like other such fantasy creators, doesn’t tell us where the money comes from ultimately, but I would suggest that he gives us some clues.

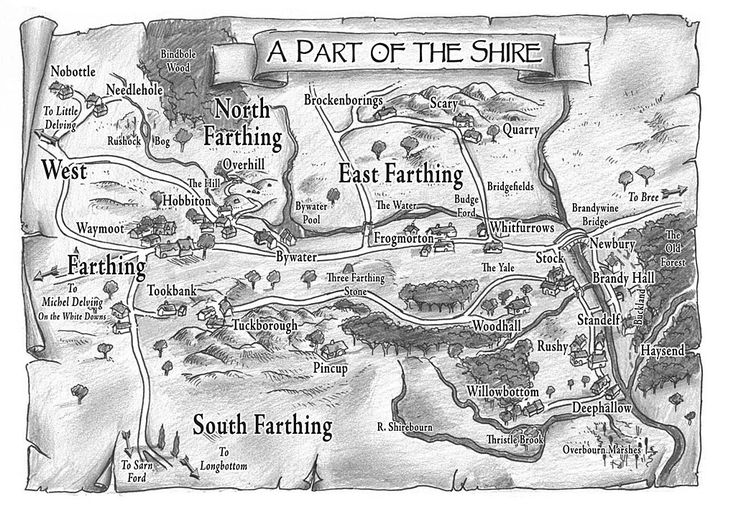

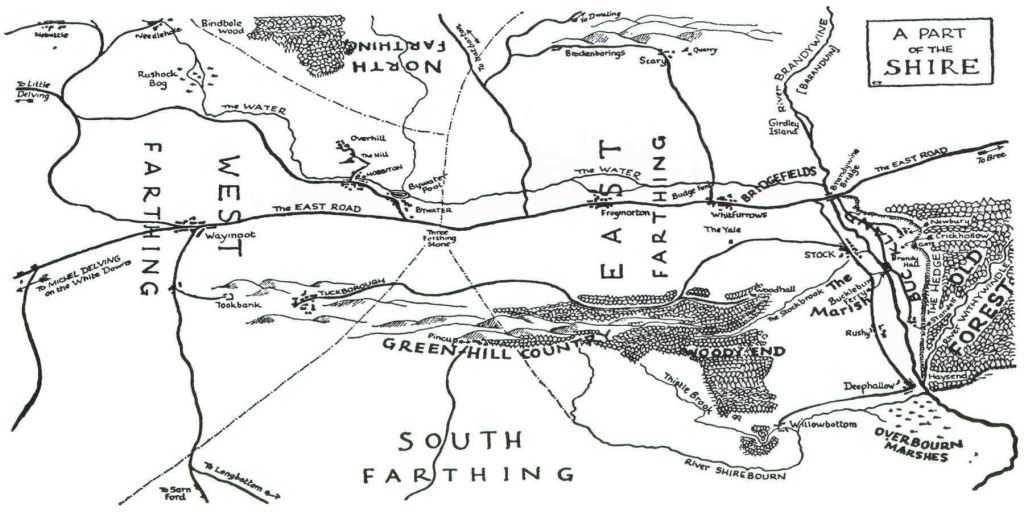

We can begin with the Shire itself. It’s not a large place—

(JRRT/Christopher Tolkien?)

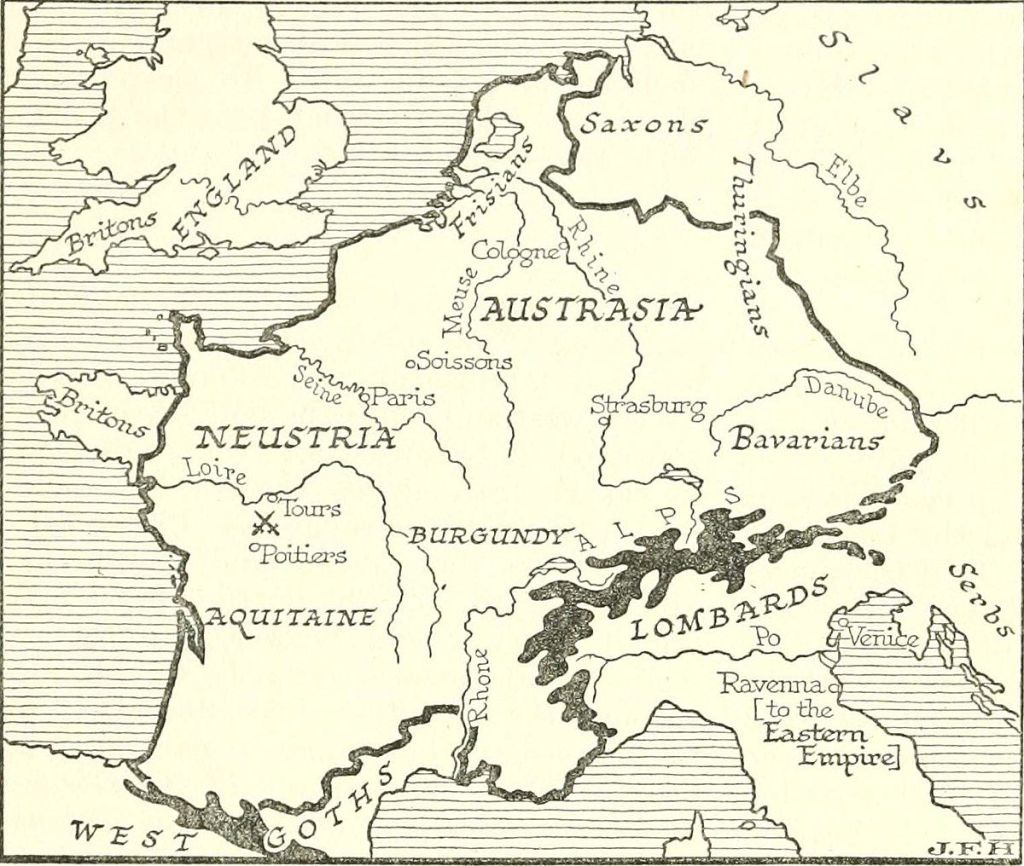

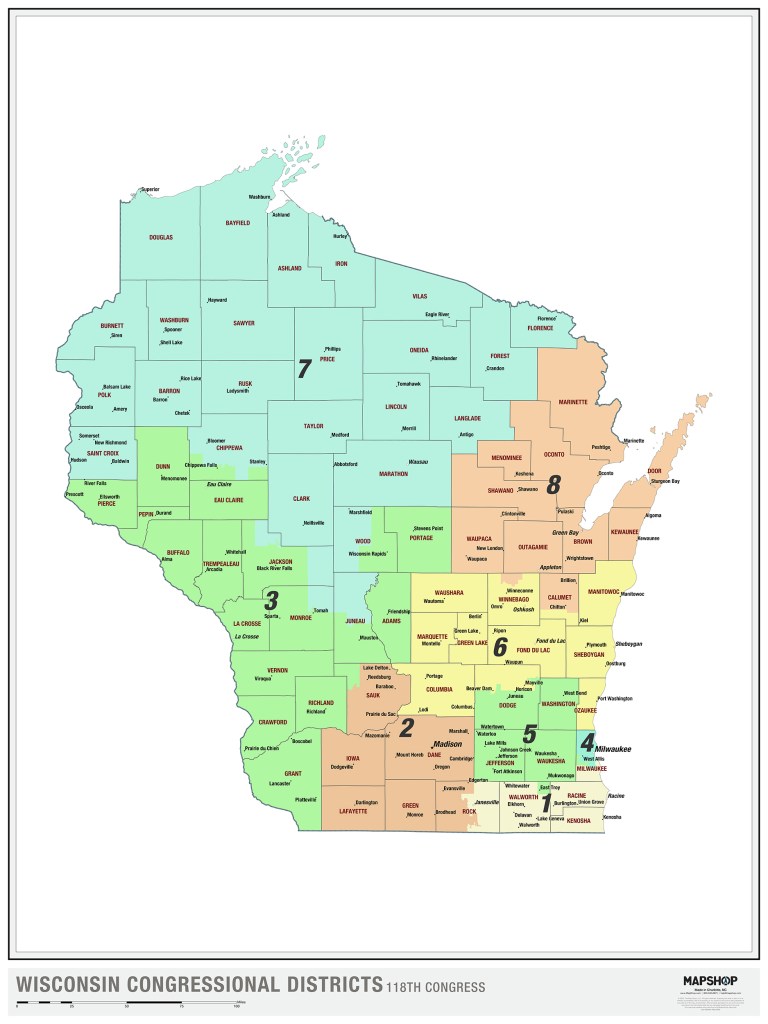

“Forty leagues it stretched from the Far Downs to the Brandywine Bridge, and fifty from the northern moors to the marshes in the south.” (The Lord of the Rings, Prologue I: “Concerning Hobbits”) If we take about 3 miles per league (4.8km), then 40 leagues = 120 miles (193km), and 50 leagues = 150 miles (241km) and yet it’s divided into quarters, suggesting that this was done for some sort of administrative purposes, cutting it down into more manageable sections. As there’s voting, perhaps the Shire is broken up into voting districts, as it is the method used here, in the US.

And, just as likely, it may be done for tax purposes—after all, how else is money raised for police, post, and infrastructure?

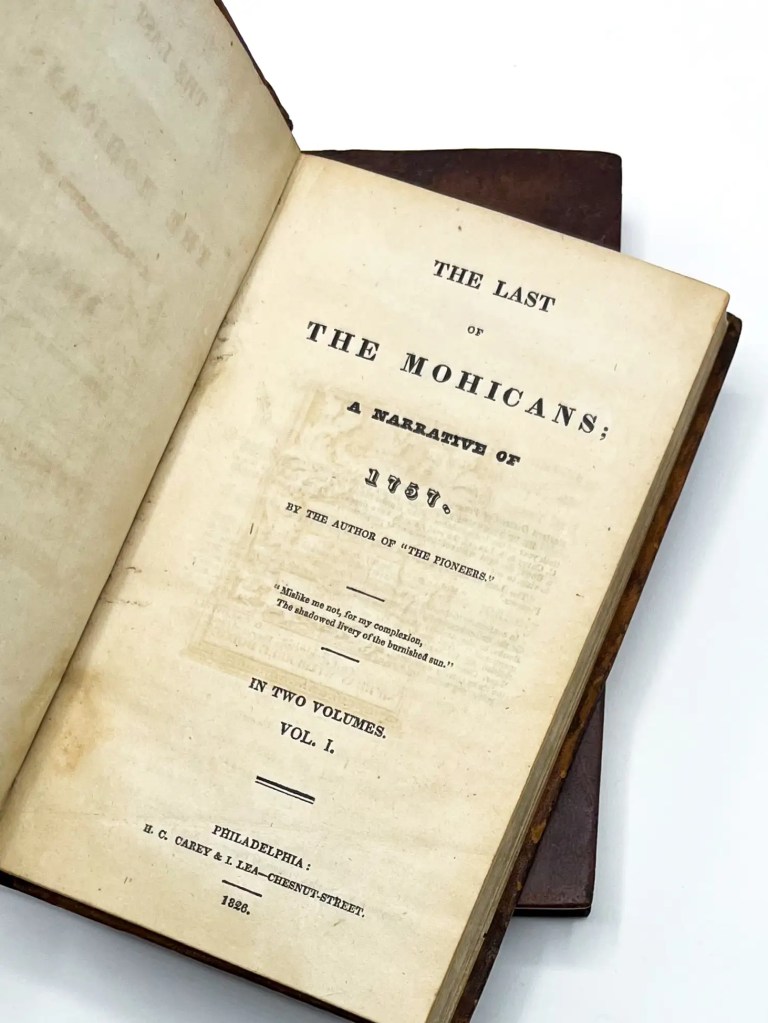

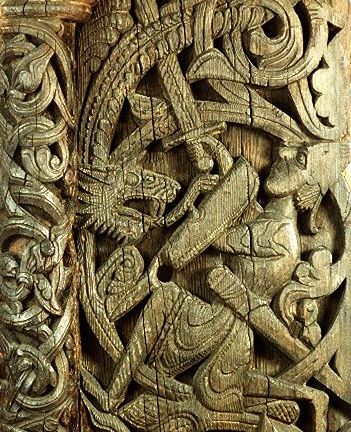

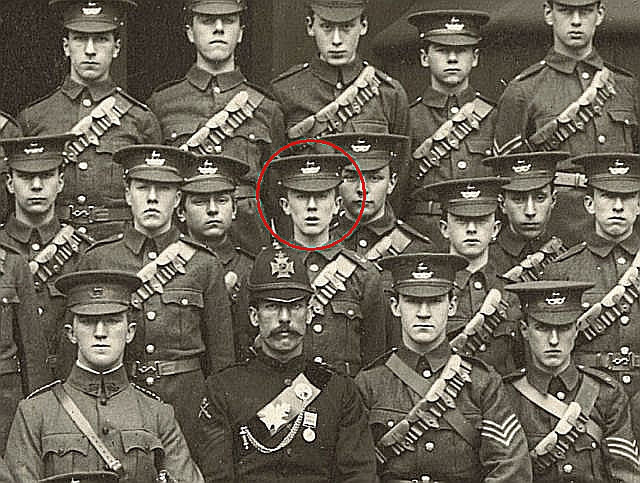

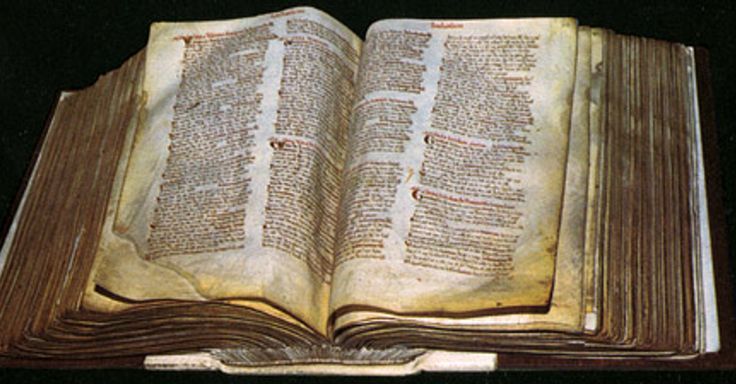

Tolkien would have been well aware that the Anglo-Saxons were sophisticated bureaucrats, producing detailed records—which the Normans took over in the so-called “Domesday Book”,

a late Anglo-Saxon joke on taxes being as sure and as unforgiving as the Last Judgment.

Not all of the volumes survive from the original survey of the 1080s, but what does survive breaks down the countryside by shires (sound familiar?), listing in great detail who owns what and how much tax does he pay on it. (For more on this incredibly interesting document see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domesday_Book )

One can imagine, then, the Shire equivalent, each of the farthings listed and, beneath each, the villages, farms, and private dwellings, with the name of the owner, what he possesses, and what he owes. The North Farthing would then include:

NORTH FARTHING

Overhill

The Hill

in which would be “Bag End”, “Bilbo Baggins”, what property produces revenue, and what taxes he owes for it

Hobbiton

The king who had originally granted land to the Hobbits was Argeleb II, in TA1601, but it’s clear that, as the Northern Kingdom faded, so did the Hobbits’ memory of Numenorean kings, except in their folklore:

“But there had been no king for nearly a thousand years…Yet the Hobbits still said of wild folk and wicked things (such as trolls) that they had not heard of the king. For they attributed to the king of old all their essential laws; and usually they kept the laws of free will, because they were The Rules (as they said), both ancient and just.” (The Lord of the Rings, Prologue I: “Concerning Hobbits”)

As they kept “The Rules”, however, we can presume that the Hobbits maintained their obligation to Argeleb, who had died in TA1670, as the Bridge of Strongbows was still standing when Frodo and his friends arrived there in TA3019. Soon after, however, a new king appeared, Elessar (aka Aragorn II), and we might wonder: what would he demand of the Shire? After all, the War of the Ring had caused tremendous damage to Gondor and it’s clear that the new king had plans to rebuild Arnor (Aragorn travels to the site of the old northern capital, Annuminas, in TA1436 The Lord of the Rings, Appendix B, “Later Events Concerning the Members of the Fellowship of the Ring”) and so we’re back to economics: would the return of the king mean, as the title of this piece suggests, tax returns? Certainly the first Norman king, William, pretty quickly set his clerks to work wringing every penny they could out of local land-holders.

We aren’t told if the Shire was required to continue the agreement made so many centuries ago with Argeleb, but the new king was clearly very grateful, at least to certain Hobbits, and:

“[SR—Shire Reckoning]1427…King Elessar issues an edict that Men are not to enter the Shire, and he makes it a Free Land under the protection of the Northern Sceptre.” (The Lord of the Rings, Appendix B, “Later Events Concerning the Members of the Fellowship of the Ring”)

Presumably, this lifts the responsibility for royal taxes, but, as the king visits his old friends at the bridge in FA1436, (The Lord of the Rings, Appendix B, “Later Events Concerning the Members of the Fellowship of the Ring”) I think that we can also presume that the ancient infrastructure agreement is still in force, even if the king doesn’t cross the bridge.

As for the post and the police? We have a modern expression which mirrors the thinking behind the ancient sad joke about the “Domesday Book”: “nothing is sure in this life except death—and taxes”.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

To add another proverbial expression, when it comes to their taxes, perhaps the Hobbits would cross that bridge when they came to it,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O