Tags

AI, I Robot, Isaac Asimov, Karl Capek, robots, RUR, science fiction, Tolkien

Welcome, dear readers, as ever.

AI seems to be everywhere and talked about all the time, sometimes in the kind of excited tones that earlier centuries used for STEAM! ELECTRICITY! THE INTERNAL COMBUSTION ENGINE! NUCLEAR POWER! COMPUTERS! and sometimes in less than enthusiastic voices which point out the pitfalls, including the (apocryphal? urban legend? true?) story about the computer which refused to turn itself off, or the one which supposedly tried to blackmail its user (possibly the same story?).

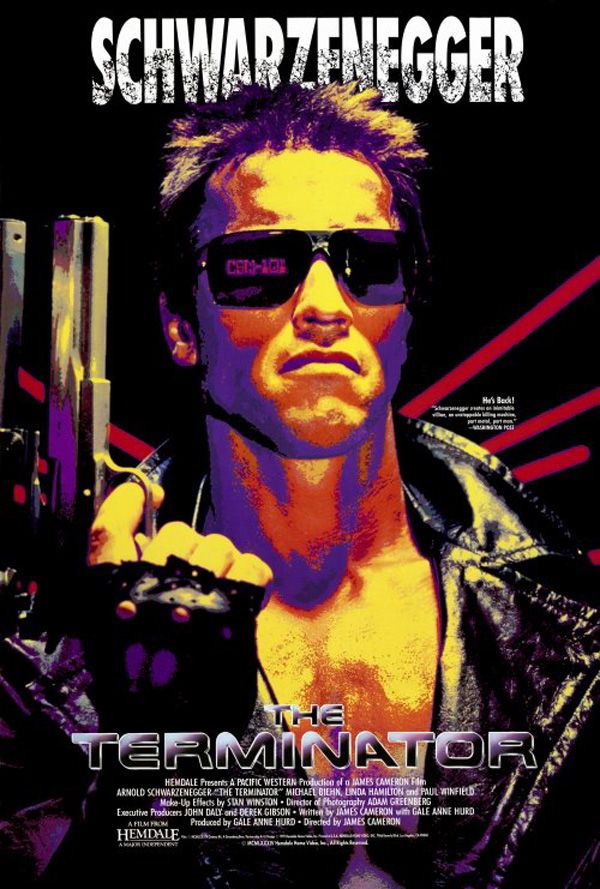

The latter, for me, has brought up this—

and this fragment of dialogue, where the Terminator’s target is being given a crash course by her protector in why she is that target:

“SARAH

I don’t understand…

REESE

Defense network computer. New.

Powerful. Hooked into everything.

Trusted to run it all. They say it

got smart…a new order of intelli-

gence. Then it saw all people as

a threat, not just the ones on the

other side. Decided our fate in a

micro-second…extermination.”

(if you’d like to read what appears to be a late draft of the screenplay, see:

https://assets.scriptslug.com/live/pdf/scripts/the-terminator-1984.pdf?v=1729115040 )

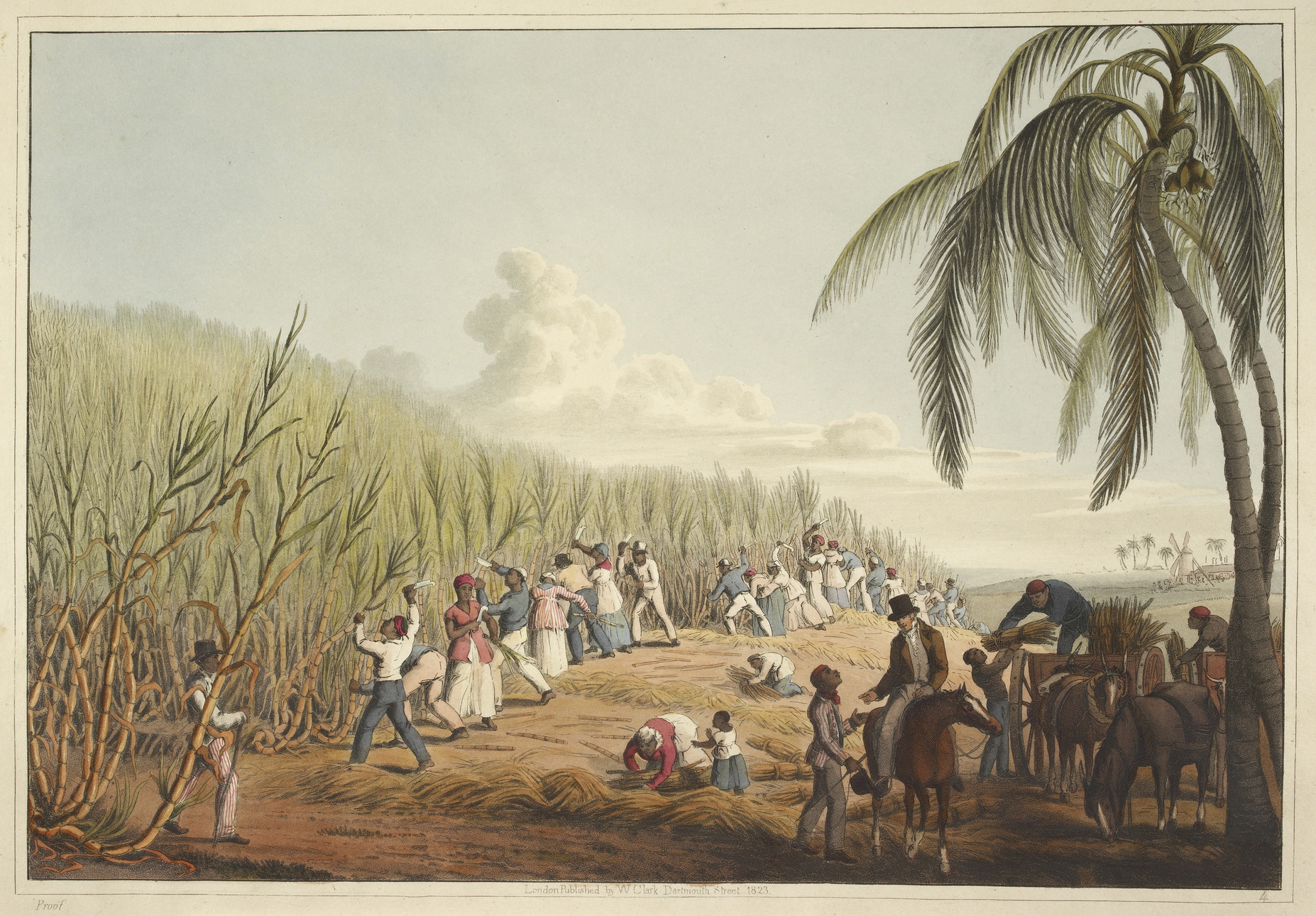

This uneasiness about new technology—and robots, in particular, is hardly new. In the early 20th century, as technology was rapidly accelerating, we see Karl Capek ‘s (that’s CHA-pek), 1890-1938,

1920 play R.U.R.,

which stands for “Rossum’s Universal Robots”, a company which is supplying the world with mechanical workers, as one of the main characters says of the formula which produced the original successful models:

“Dr. Gall. We go on using it and making Robots. All the universities are sending in long petitions to restrict their production. Otherwise, they say, mankind will become extinct through lack of fertility. But the R. U. R. shareholders, of course, won’t hear of it. All the governments, on the other hand, are clamoring for an increase in production, to raise the standards of their armies. And all the manufacturers in the world are ordering Robots like mad.” (R.U.R., Act II)

And you can see here the tensions which such an invention can—and do– bring: those who can see the future are concerned, those who are only interested in profit—or death—are boosting production, regardless of any hazard.

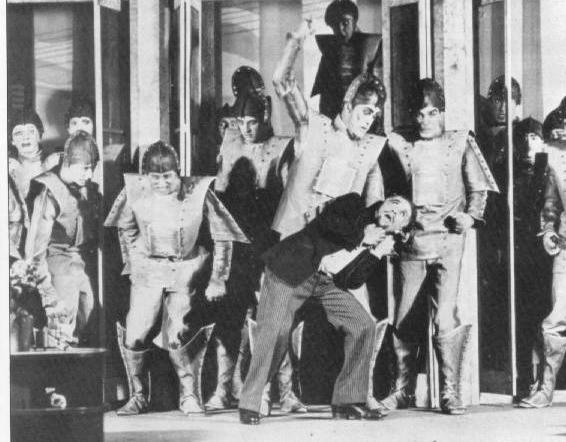

This all comes apart when a limited number of robots (from the Czech word roboti, “workers”) gain sentience—“got smart…a new order of intelligence”—you can see that uneasiness started early—realize that they are far more intelligent and stronger, with more endurance, than humans, and revolt, determined to wipe out humanity and replace it with themselves.

They rally all of the other robots and, by the play’s end, only one human appears to be left. That ending is perhaps a little more hopeful, but I won’t spoil it for you—you can read it (in its first English translation) here: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/59112/59112-h/59112-h.htm

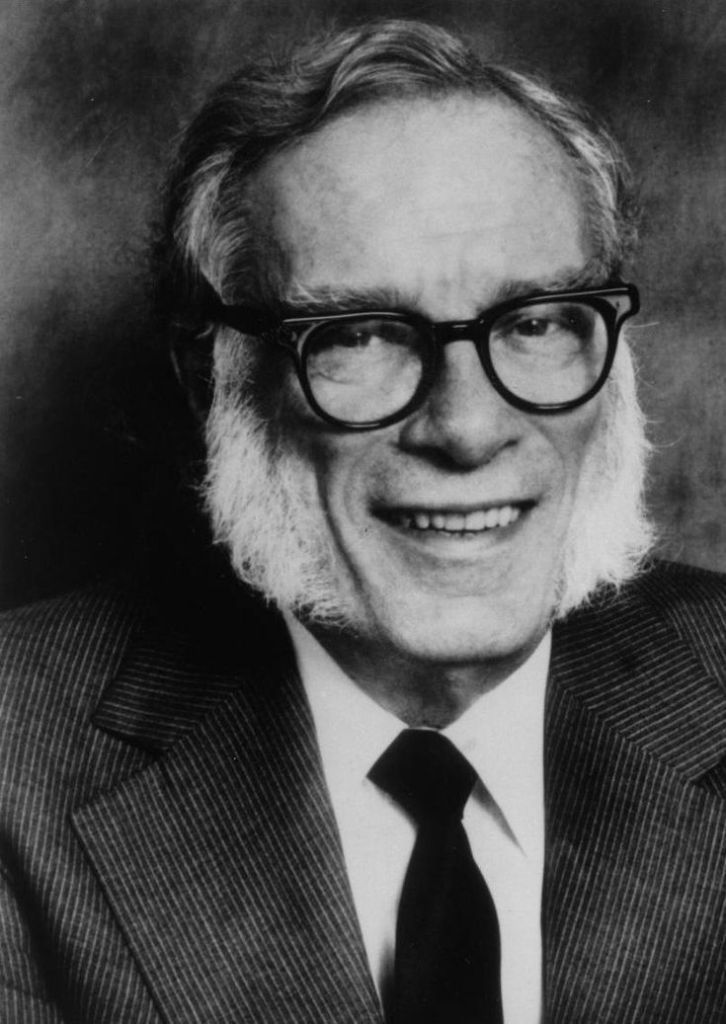

Tolkien was somewhat of a science fiction fan, enjoying, in particular, the work of Isaac Asimov, 1920-1992. (See the second footnote to a letter to Charlotte and Denis Plimmer, 8 February, 1968, Letters, 530)

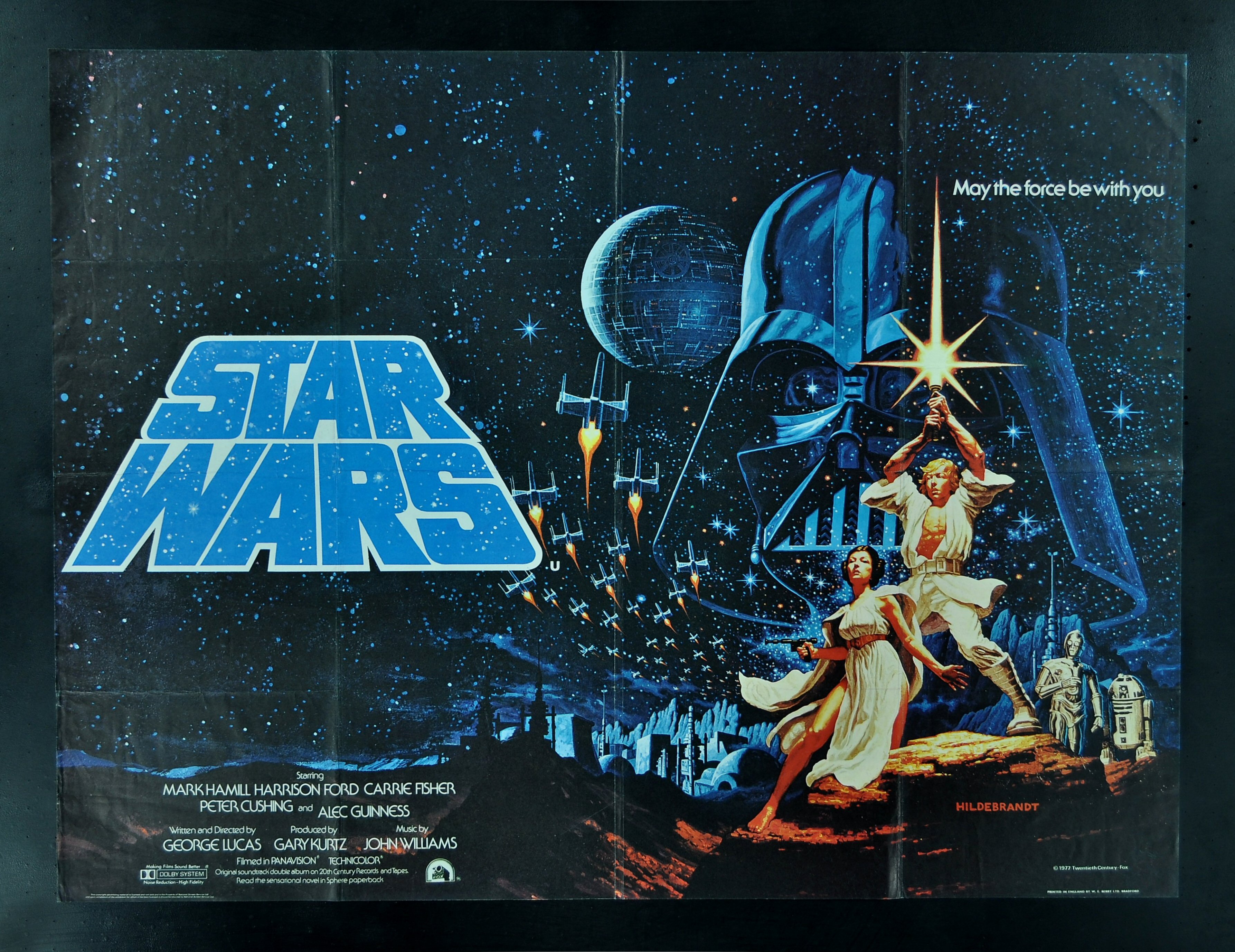

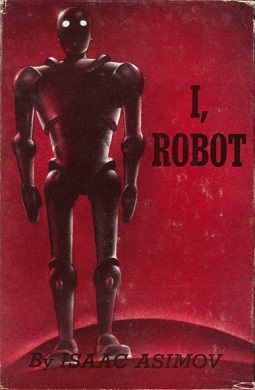

He doesn’t list what he had read, unfortunately, but, as the letter in which he mentions (and misspells) Asimov dates from 1967, I’ve wondered whether he had read Asimov’s 1950 classic collection of short stories, I, Robot,

the first of a series of “Robot” novels, beginning with The Caves of Steel, 1954.

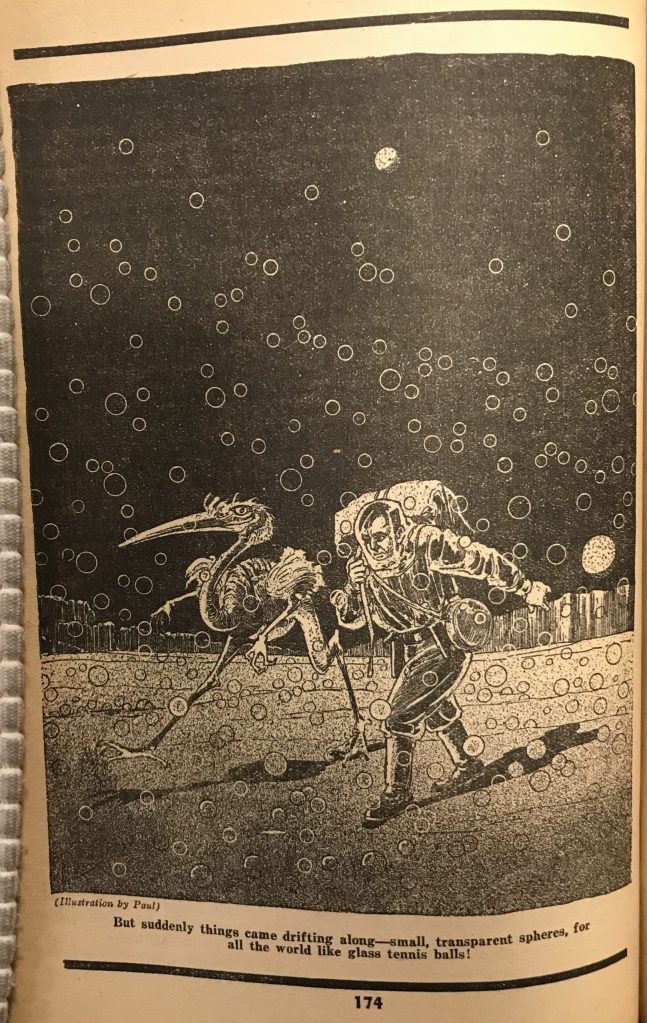

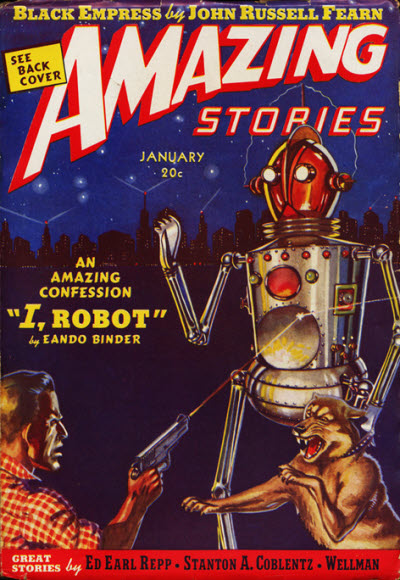

To Asimov’s annoyance, the publisher took the title of that short story collection from a 1939 short story by “Eando Binder” (pen name of Earl and Otto Binder) published in the January, 1939, issue of Amazing Stories.

It’s an odd little tale in which a robot, already an object of local fear, is mistaken for the murderer of his scientist creator (actually killed in an accident) and hounded to the point at which he commits mechanical suicide, the entire story being, as he terms it, his “confession”. You can read it here: https://archive.org/details/Amazing_Stories_v13n01_1939-01_cape1736 And read more about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I,_Robot_(short_story)

Asimov tells us that he had read and been inspired by the 1939 short story, but his 1950 collection, of which a number of the stories had been published earlier, is told from the outside, and is a very interesting series of what might be seen as profiles of robots and their behavior over a number of years and events, narrated by Dr. Susan Calvin, a “robopsychologist”. You can read the collection here: https://dn720004.ca.archive.org/0/items/english-collections-1/I%2C%20Robot%20-%20Isaac%20Asimov.pdf And read about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I,_Robot

One aspect of Asimov’s early stories is that robot behavior—almost as if the creators there had seen or read R.U.R. and paid attention to the warning implied (and I’ll bet that Asimov, who appears to have read everything, probably had read the play)- – is governed by a set of basic laws, first appearing in the story “Runaround” in I, Robot:

“Powell’s radio voice was tense in Donovan’s ear: ‘Now, look, let’s start

with the three fundamental Rules of Robotics—the three rules that are built

most deeply into a robot’s positronic brain.’ In the darkness, his gloved

fingers ticked off each point.

‘We have: One, a robot may not injure a human being, or, through

inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.’

‘Right!’

‘Two,’ continued Powell, ‘a robot must obey the orders given it by

human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.’

‘Right!’

‘And three, a robot must protect its own existence as long as such

protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.’

‘Right! Now where are we?’ “

As we confront the extremely rapid growth of AI, still so much a mystery, even if we don’t believe stories about increasing—and potentially menacing—sentience, I’m only hoping that, as I suppose Tolkien did, at least some of the designers have read “Runaround” and built those laws into their experimental models.

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

Be interested in technology, but be aware, as Asimov was, that it should be addressed critically,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

For more on the history of automata and droids, see: “Eyeing Robots”, 8 April, 2021. Capek came from a very interesting family. Read about him and them here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karel_%C4%8Capek

PPS

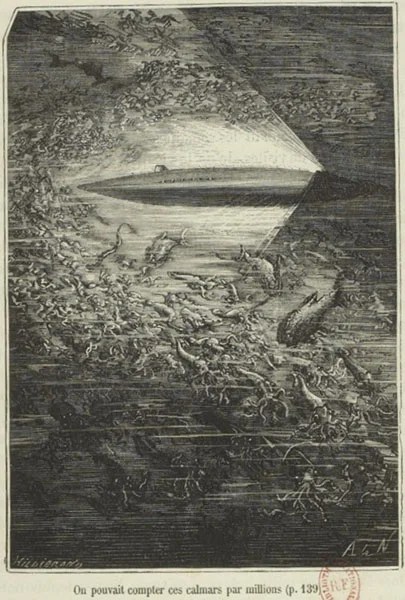

As Tolkien was an admirer of Asimov, so Asimov was an admirer of Tolkien, see his article, “All and Nothing” in Fantasy and Science Fiction, January, 1981, which you can read here: https://archive.org/details/Fantasy_Science_Fiction_v060n01_1981-01/mode/2up