Tags

augury, Belshazzar, class in the Shire, Daniel, Dwarves, Fantasy, Jerome, literacy in Middle-earth, reading, Rohirrim, Sam Gamgee, scribes, the handwriting on the wall, Tolkien, Writing

As always, dear readers, welcome.

Belshazzar, the king of the Babylonians, was having a lovely party—

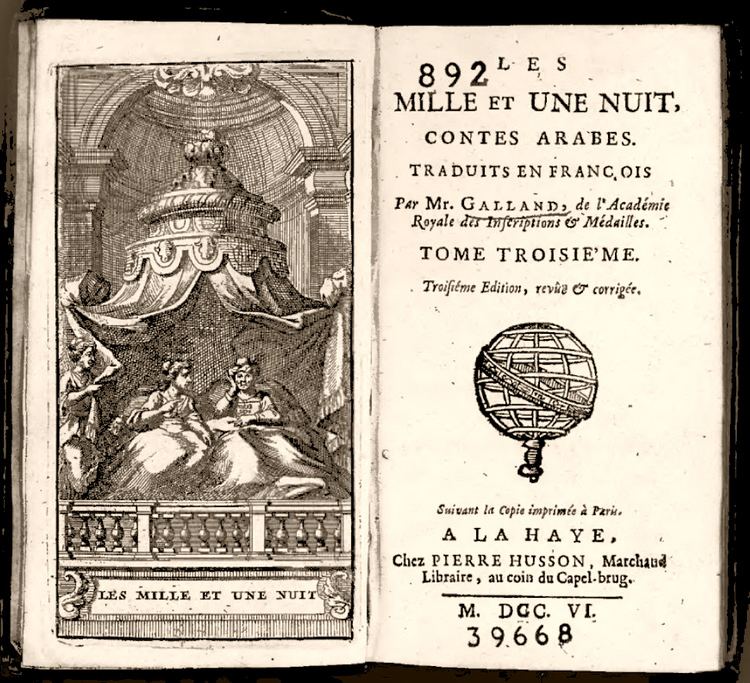

“Baltassar rex fecit grande convivium optimatibus suis mille: et unusquisque secundum suam bibebat aetatem.”

“Belshazzar held a great banquet for a thousand of his elite and each one was drinking according to his time of life.”

But, wishing to up the fun, he decided to make the party a bit more lavish—

Praecepit ergo jam temulentus ut afferrentur vasa aurea et argentea, quae asportaverat Nabuchodonosor pater ejus de templo, quod fuit in Ierusalem, ut biberent in eis rex, et optimates ejus, uxoresque ejus, et concubinae.

“And so now, being drunk, he ordered that the golden and silver vessels which Nebuchadnezzar, his father, had carried away from the temple which had been in Jerusalem be brought in so that the king and his nobles and his wives and concubines might drink in them.”

[“fuit” here is the perfect form and might be translated “has been”, but that form can suggest a permanent state, the pluperfect, suggesting that there would be no more Jerusalem.]

and then things go very wrong–

“In eadem hora apparuerunt digiti, quasi manus hominis scribentis contra candelabrum in superficie parietis aulae regiae: et rex aspiciebat articulos manus scribentis.”

“In the same hour, there appeared fingers, like a man’s hand, opposite the lampstand, writing on the surface of the wall of the royal hall, and the king was staring at the joints of the hand writing.”

(Rembrandt—who clearly had no idea what the real Babylonian king would have worn, but settled for something right out of the visit of the Magi, which was undoubtedly good enough for his audience, who would have had no more idea than he did)

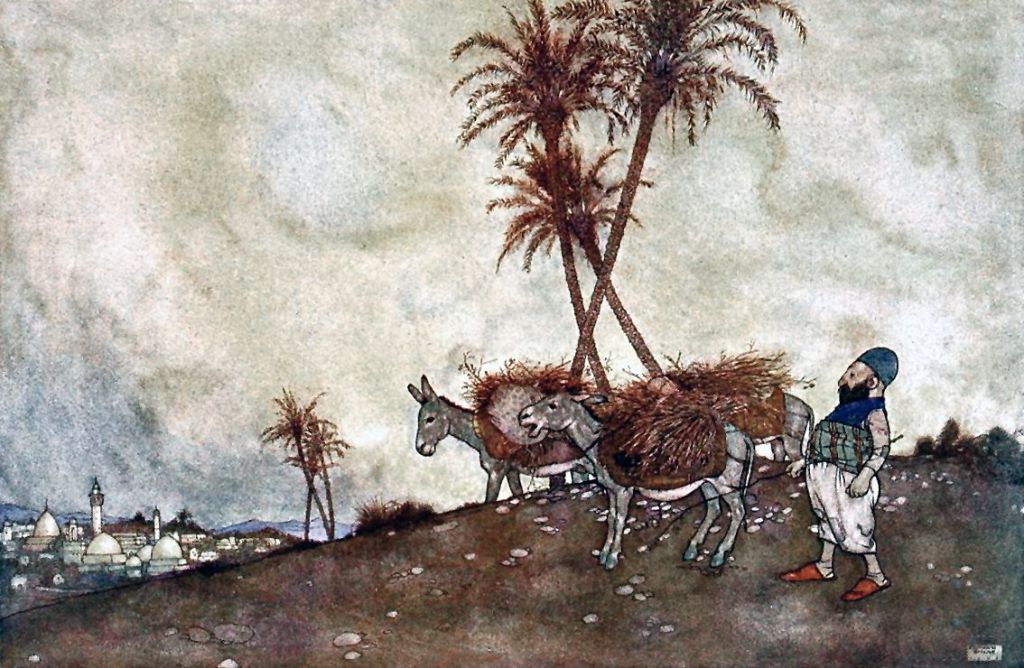

Needless to say, this was a bad omen, but one his own counselors couldn’t interpret, as the message was not in Babylonian. His queen, however, recommended that a Jewish interpreter, Daniel, be summoned, who arrived and interpreted the writing, which may have included some rather fancy word-play, but which meant: “You are not long on the throne and your kingdom is about to become the property of the Persians.”

(All Latin translations are mine from Section 5 of “The Book of Daniel”. The Latin text is from Jerome’s 4th-century translation, which you can read, with an English translation, here: https://vulgate.org/ot/daniel_5.htm For more on the message, see: https://www.christianitytoday.com/2024/11/andrew-wilson-spirited-life-daniel-writing-on-wall-babylon/ For more on the historic Belshazzar—an ironic name as far as the ancient Hebrews must have been concerned, as it means “[the god] Bel [aka Baal] protect the king” which the Book of Daniel indicates that he certainly didn’t!—see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belshazzar )

Behind this story lies not only the status of Daniel as prophet and interpreter, and the idea that the Hebrew God is not to be messed with, even by kings, but also, for this posting, the importance of writing—the omen isn’t, like so many others, based on the flight of birds or the liver of a sheep or the behavior of chickens,

(for more on such practices see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augury )

all things which the ancient world would have thought significant–but on something handwritten (literally) on a palace wall. This is clearly so unusual that its significance is immediately multiplied, and which, since Daniel can not only interpret it, but, to do so, he can read it, tells us something more about Daniel: he is literate.

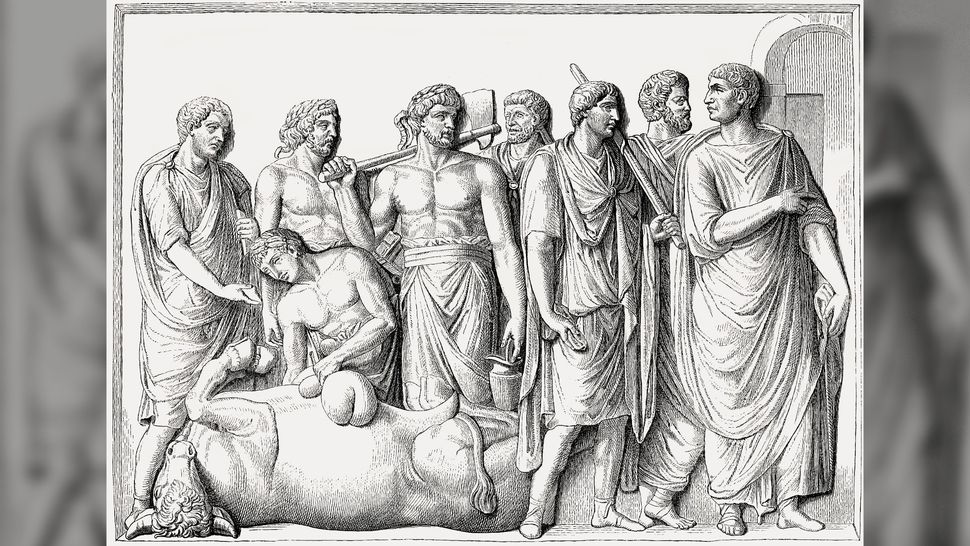

Because we in the modern West live in such a literate world ourselves, it’s sometimes hard to understand earlier worlds where literacy was not the norm. Could Belshazzar read? Probably not: that was the job of technical people, scribes,

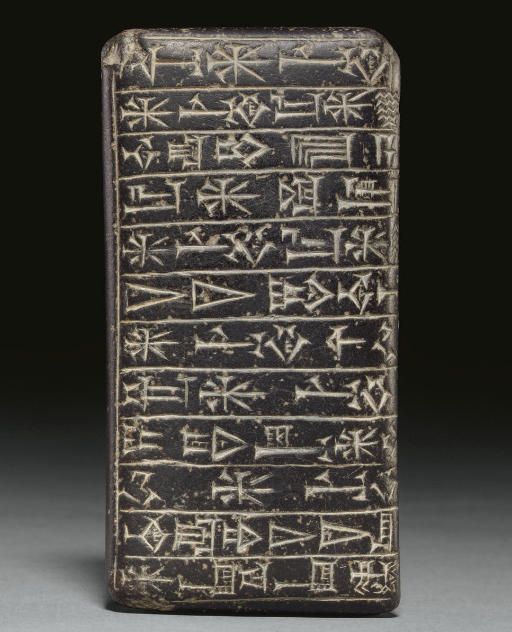

(These are actually Sumerians, but can stand in for Babylonian scribes, as the Babylonians used the writing system, cuneiform,

which the Sumerian scribes had invented.)

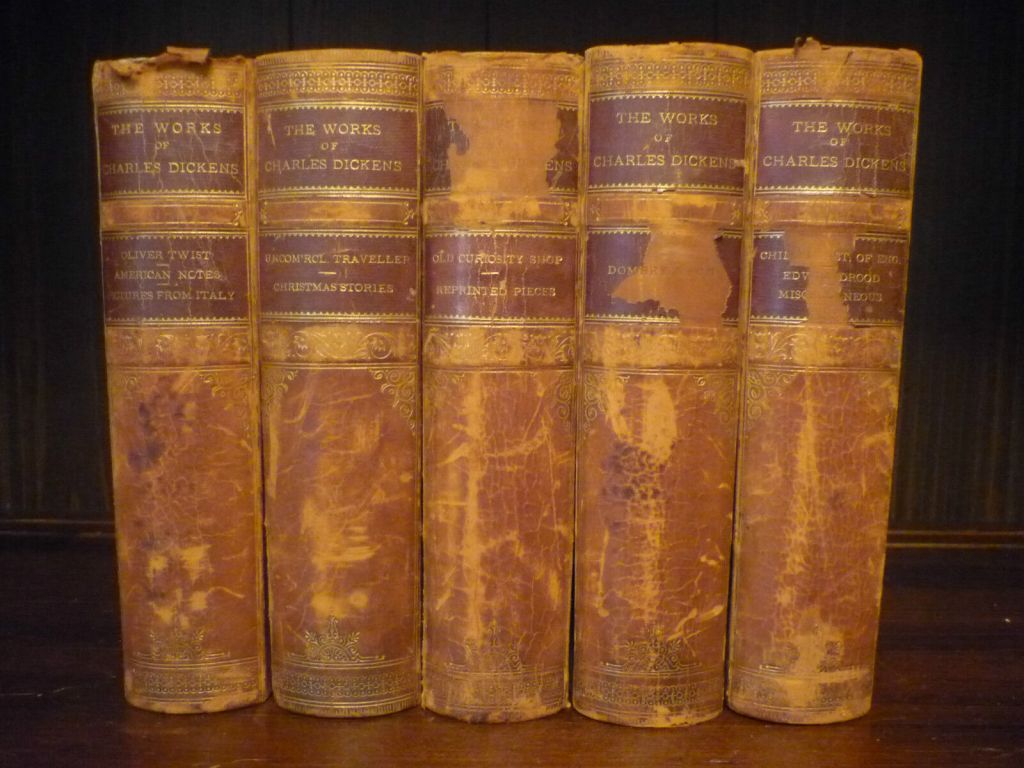

whom rulers could call upon when needed, as we see in ancient and medieval societies in general. Literacy was a skill, like carpentry or masonry, and limited in the number of people who could practice it. Could this have been true in Middle-earth, based as it is upon the medieval world of our Middle-earth, as well?

Gondor appears to have had a long tradition at least of extensive record-keeping, as we hear from Gandalf:

“And yet there lie in his hoards many records that few even of the lore-masters now can read, for their scripts and tongues have become dark to later men.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 2, “The Council of Elrond”)

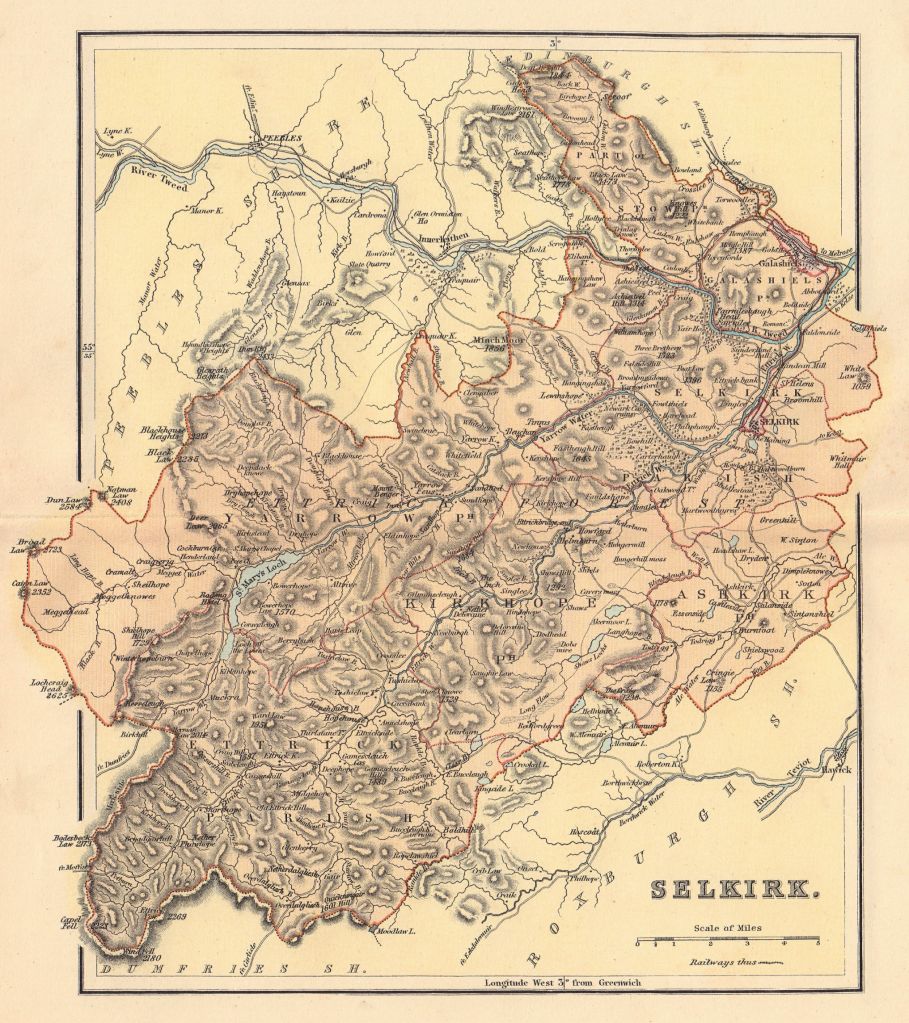

As for the Rohirrim, I would guess that, although there may have been some literacy, much of their past—and possibly their present—was preserved in oral tradition, as Aragorn says of Meduseld:

“But to the Riders of the Mark it seems so long ago…that the raising of this house is but a memory of song.” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 6, “The King of the Golden Hall”)

And Theoden says to Aragorn:

“Will you ride with me then, son of Arathorn? Maybe we shall cleave a road, or make an end as will be worth a song—if any be left to sing of us hereafter.” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 7, “Helm’s Deep”)

In the Prologue to The Lord of the Rings, we are told that the Hobbits as a whole had had potential literacy for some time, in fact, from their days of moving westwards towards what would become the Shire:

“It was in these early days, doubtless, that the Hobbits learned their letters and began to write, after the manner of the Dunedain, who had in their turn long before learned the art from the Elves.” (The Lord of the Rings, Prologue I, “Concerning Hobbits”)

As in the case of other medieval worlds, however, this was seemingly not general literacy, although rather than being the possession of a specialized class, as in Babylon or ancient Egypt,

it might, instead, have been a mark of class.

Consider Sam Gamgee. His father is the gardener for Bilbo Baggins and Sam is his assistant.

(Robert Chronister)

From his position—and from the way he addresses his “betters” as “Mister”, while they address him by his first name—it’s clear that Sam and his father are not of the same social class as the Bagginses. And so, when the Gaffer says:

“Mr. Bilbo has learned him his letters—meaning no harm, mark you, and I hope no harm will come of it.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 1, “A Long-Expected Party”)

This appears to be what we might call a mark of that class difference: Bilbo, a ‘gentleman” can read, although, as we hear of no academies in the Shire, presumably through home-schooling, implying that there was at least one other person in his family’s household who could also read and who had taught him. Considering the Gaffer’s potential uneasiness about it—why should there be harm in being able to read?—I think that we can imagine that the Gaffer himself could not—and himself was aware of the class distinction (Sam might get ideas “above his station”?).

And yet it’s to Sam that Frodo passes the book begun so long ago by Bilbo:

“ ‘Why, you have nearly finished it, Mr. Frodo!’ Sam exclaimed. ‘Well, you have kept at it, I must say.’

‘I have quite finished, Sam,’ said Frodo. ‘The last pages are for you.’ “ (The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 9, “The Grey Havens”)

Daniel’s literacy gives him the ability to read the Hebrew God’s warning to Belshazzar, establishing his importance in the story (which continues, as he becomes the confidant and friend of the new king, Darius.)

And here we see the real reason JRRT had given Sam literacy: not that he might read Bilbo/Frodo’s efforts, but that he might write and therefore complete the story of The Lord of the Rings, and thus add one more element to his importance in the narrative.

In our next posting, however, we will examine another use of writing and reading—and a much less benign one.

Thanks, as always for reading.

Stay well,

Delight in the fact that you can read,

And remember that there’s always

MTCIDC

O

PS

As to evidence of general literacy in the Shire, we see, in “The Scouring of the Shire”, some public notices—a sign on the new gate on the bridge over the Brandywine (“No admittance between sundown and sunrise”) and an anonymous hobbit calls out “Can’t you read the notice?” In the watch house just beyond we see: “…on every wall there was a notice and list of Rules”. As far as I can tell, however, these are the only public signs we see in Middle-earth and seem to me more about Authority than literacy. Just the fact that they’re there must have an effect upon cowed hobbits, even if they can’t read.

PPS

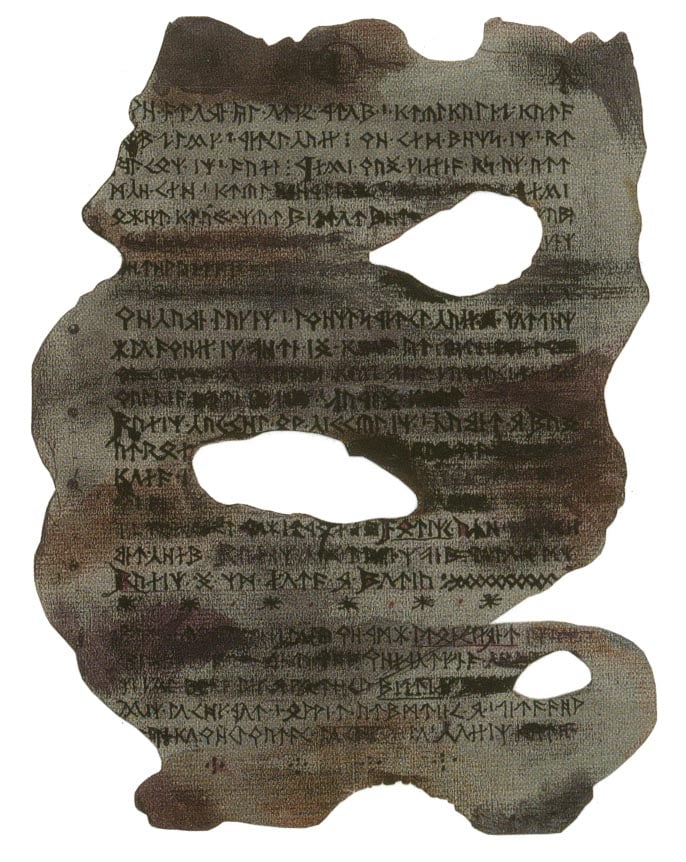

For completeness sake, although we have only bits and pieces of dwarvish, we can say that at least some dwarves were literate, evidence being the fragmentary account of the reworking of Moria which the Fellowship find in the Chamber of Records there,

as well as the inscription on Balin’s tomb. (for more on JRRT’s work on recreating that fragmentary record, the so-called Book of Mazarbul, see: “Aging Documents”, 31 July, 2024)