Tags

anglo-saxons, Boudica, chariots, eurasian-steppe, Huns, hybrds, Hybrids, Jacksons The Lord of the Rings, jacksons-lord-of-the-rings, Julius Caesar, Mongols, Normans, Rohirrim, Sarmatians, Scythians, Tacitus, Tolkien, Wainriders

As always, dear readers, welcome.

The title of this piece might suggest electric cars, and it definitely will mention several different wheeled vehicles, but it is actually what I hope is a little study in something Tolkien does wonderfully well: taking different elements from different times and cultures and so blending them that they become believable new wholes.

Although I don’t always agree with elements in Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings, one thing has always given me pleasure: the Rohirrim, whether en masse

or a small grouping.

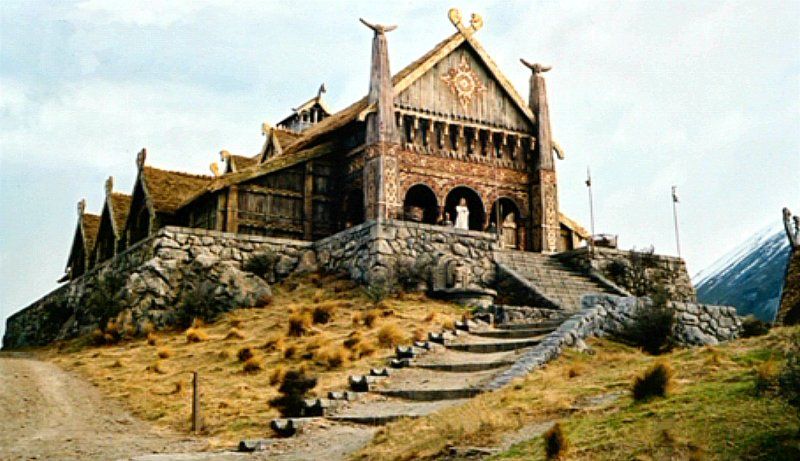

And this is true for Edoras

as well as for Meduseld.

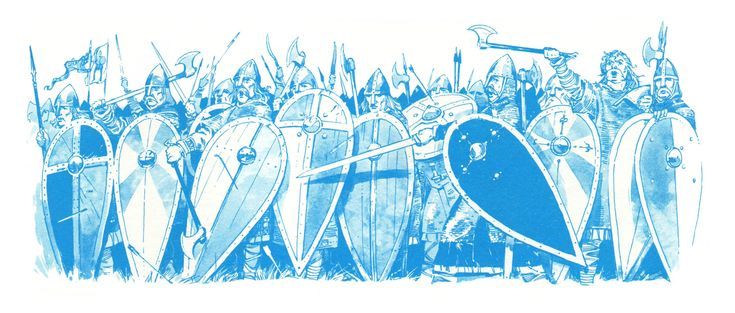

And yet they appear to be a kind of combination of peoples: on the one hand, Tolkien imagined them to be Anglo-Saxons,

(Peter Dennis)

a people who primarily fought on foot, as at their last two major battles, Stamford Bridge,

(Victor Ambrus—who worked for years with the popular British archeology series, Time Team—which is available on YouTube and much recommended)

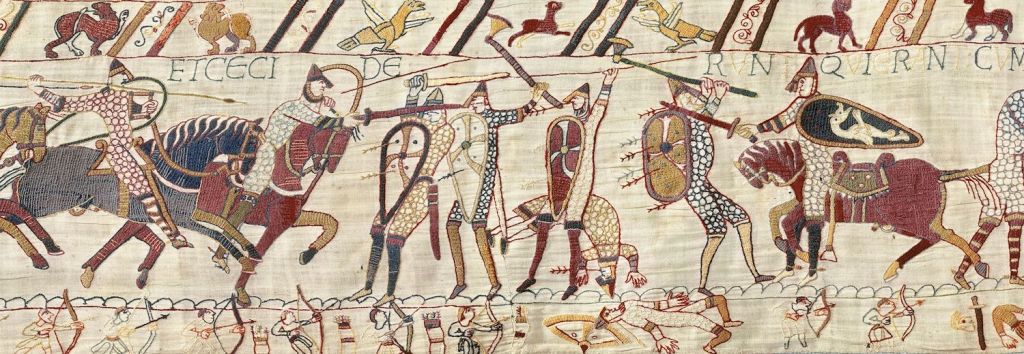

where they defeated another infantry force, the Vikings, and Hastings,

(Artist?)

in which they were overwhelmed at the battle’s conclusion by Norman cavalry.

(From the wonderful “Bayeux Tapestry”—actually the “Bayeux Embroidery”—if you’d like to see the whole thing, look here: https://www.bayeuxmuseum.com/en/the-bayeux-tapestry/discover-the-bayeux-tapestry/explore-online/ To my knowledge, there’s nothing like it from the Middle Ages for depicting a specific series of events in the medieval world.)

On the other hand, the Rohirrim were mounted, more like those Normans who defeated the Anglo-Saxons,

although the language they speak is, basically, a form of Old English, the language of the Anglo-Saxons. Tolkien imagined them, in fact, as looking like the Normans, as well, describing them in a letter to Rhona Beare:

“The styles of the Bayeux Tapestry (made in England) fit them well enough, if one remembers that the kind of tennis-nets [the] soldiers seem to have on are only a clumsy conventional sign for chain-mail of small rings.” (letter to Rhona Beare, 14 October, 1958, Letters, 401)

That is, their armor actually can look like this—

(By Angus McBride—and ironic, as, for all that McBride must have painted dozens of figures in chain mail, he once confessed in an interview that it was his least favorite part of illustrating, as the mail took so long to do.)

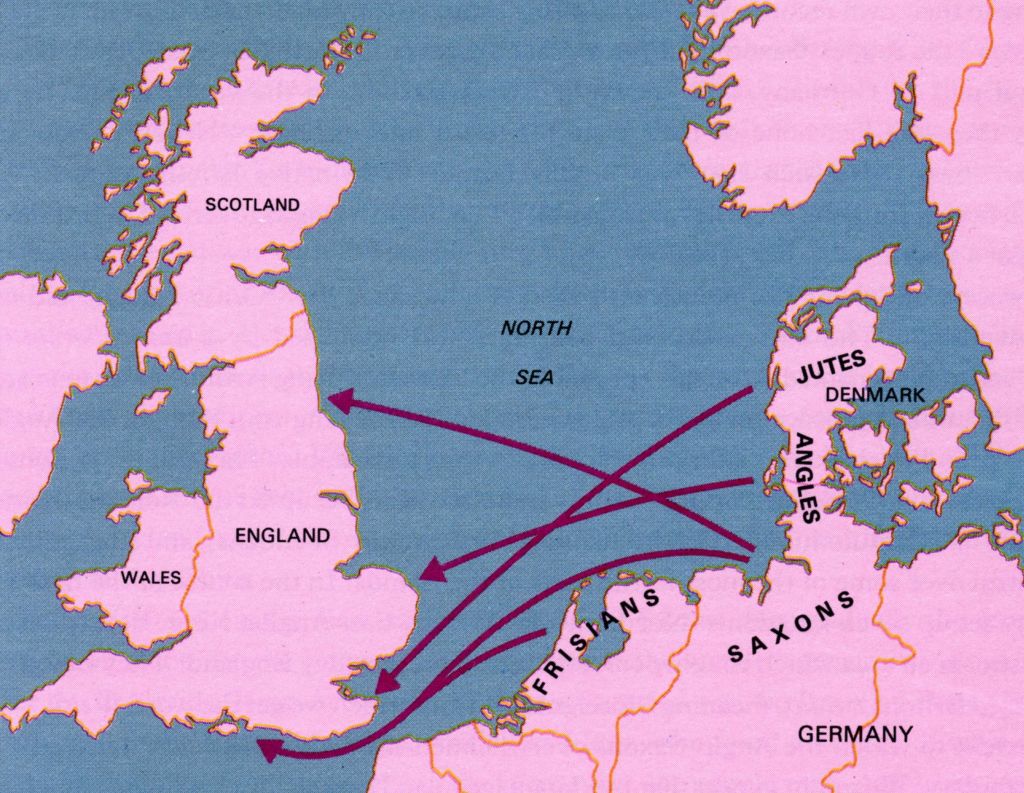

It’s also interesting to think about them as a people. Anglo-Saxons were descended from a combination of locals (Romano-British) and various groups of west-Germanic tribesmen who had either been early post-Roman invaders of Britain or Germanic tribesmen brought to Britain to protect the locals from those invaders and who had become colonizers in turn.

But who were the Rohirrim and where did they come from?

“Eorl the Young was lord of the Men of Eotheod. That land lay near the sources of Anduin, between the furthest ranges of the Misty Mountains and the northernmost parts of Mirkwood.”

(JRRT)

They had not always lived there, however:

“The Eotheod [from Old English, “Horsefolk”] had moved to those regions in the days of King Earnil II [TA 1945-2043] from lands in the vales of Anduin between the Carrock and the Gladden, and they were in origin close akin to the Beornings and the men of the west-eaves of the forest. The forefathers of Eorl claimed descent from kings in Rhovanion, whose realm lay beyond Mirkwood before the invasions of the Wainriders…They loved best the plains and delighted in horses and in all feats of horsemanship…” (The Lord of the Rings, Appendix A II “The House of Eorl”)

The combination of “They loved best the plains and delighted in horses” makes perfect sense when one thinks about comparative history in our Middle-earth. Consider the Eurasian Steppe, stretching from western China all the way to the Hungarian puszta.

This is an immense belt of grassland,

some 5000 miles (8000km) wide,

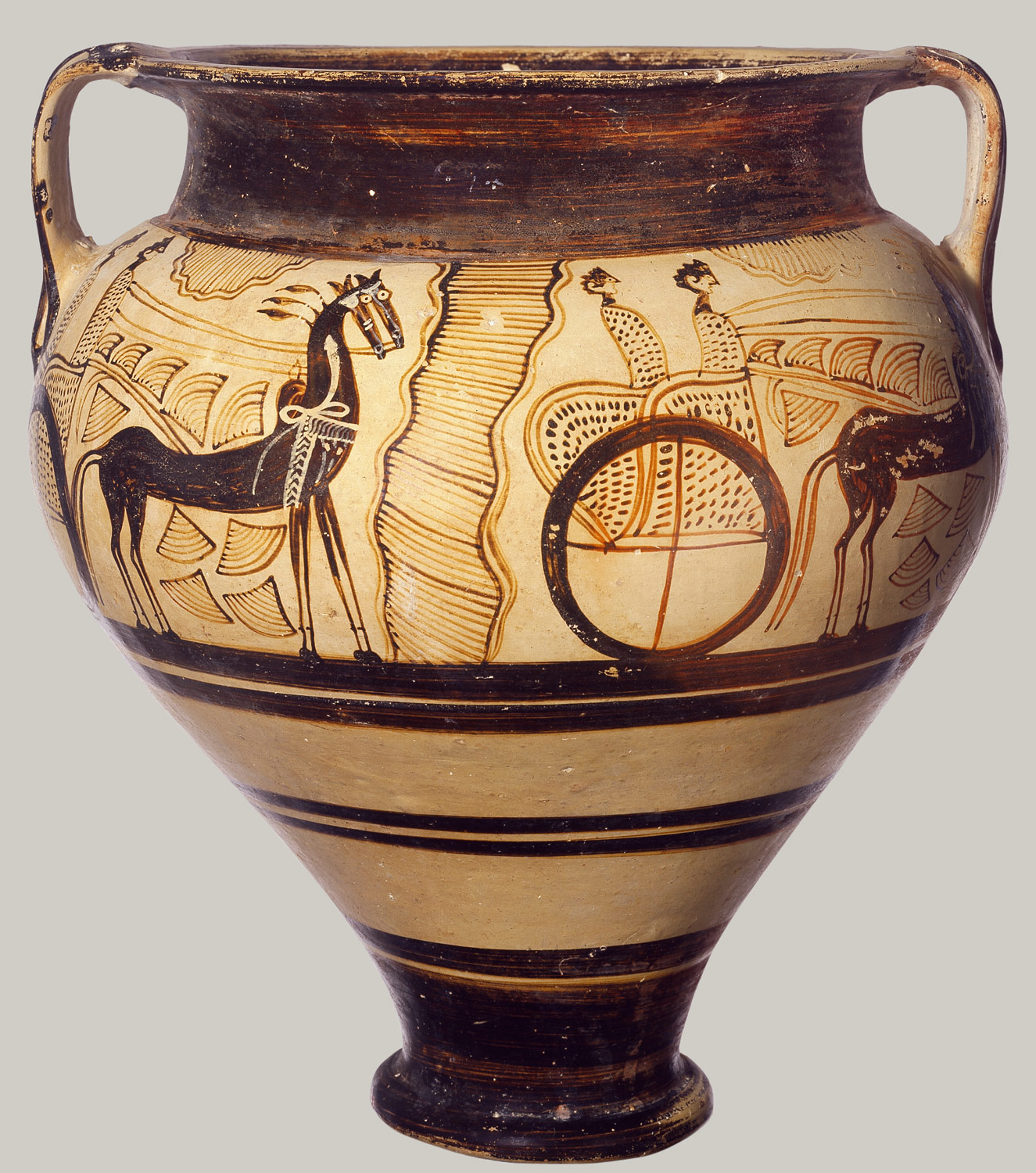

and has been the homeland of numerous horsefolk throughout history, from the Scythians

to the Sarmatians

to the Huns

(Angus McBride)

to the Mongols.

(another McBride)

All of these peoples have used the Steppe to graze their herds of horses, sometimes moving west for grazing, sometimes moving west when pressured by others further east, and sometimes as predators, like the Huns, moving west to seek new plunder.

(I haven’t been able to identify an artist for this–it has the look of late-Victorian.)

In two of these cases, whole peoples might be on the move and this is perhaps where Tolkien has gotten part of his description of those Wainriders he mentions:

“The Wainriders were a people, or a confederacy of many peoples, that came from the East; but they were stronger and better armed than any that had appeared before. They journeyed in great wains, and their chieftains fought in chariots…”

So, we can imagine that the Eotheod, pressured by the Wainriders, were forced west, as one steppe people is pushed westward by another to the east.

But Tolkien gives us another—or perhaps additional–possibility:

“Stirred up, as was afterwards seen, by the emissaries of Sauron, they made a sudden assault on Gondor…The people of eastern and southern Rhovanion were enslaved; and the frontiers of Gondor were for that time withdrawn to the Anduin and the Emyn Muil.” (The Lord of the Rings, Appendix A, IV “Gondor and the Heirs of Anarion”)

The Wainriders, then, might be both steppe peoples moving westwards, but also predators, like the Huns, or like the Mongols, who were both predators and empire-builders, and here we might see Mongols with their characteristic ger (a large round tent)—on a wagon—perhaps like the Wainriders?

(Wayne Reynolds)

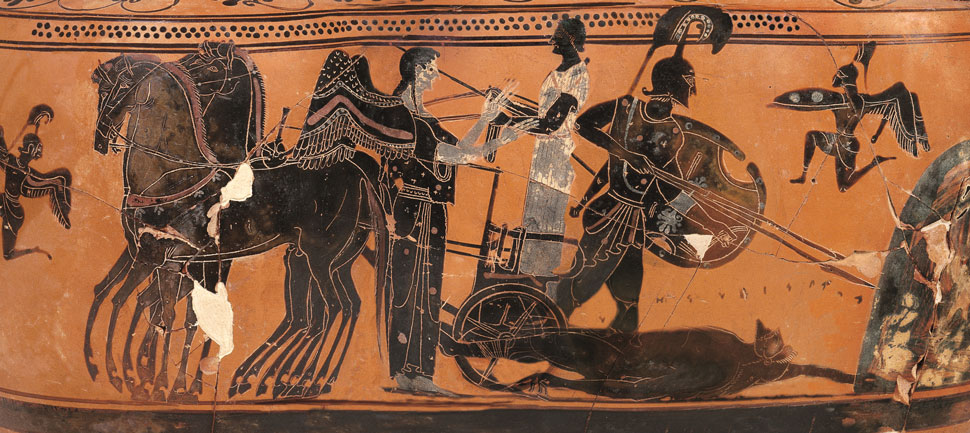

Although there is no mention in our text of the Rohirrim migrating with wagons, it’s clear from parallels in our world that the peoples who crossed the Eurasian Steppe appear to have used them regularly. But here, like the Rohirrim, we have another odd juxtaposition. The Rohirrim are Anglo-Saxons on horseback: cavalry, which was true for all of those migrants across the Steppe in our world. Chariots, however, although Tolkien says that the Wainrider chiefs fought in them (of which fact this is the only mention) were not part of those other horsefolks’ arsenals. Where did they come from?

The answer, I think, lies in the period of British history before the Anglo-Saxons and almost before the Romans, among the earlier Celtic settlers of England. Julius Caesar encountered chariots there and described their use:

Genus hoc est ex essedis pugnae. Primo per omnes partes perequitant et tela coiciunt atque ipso terrore equorum et strepitu rotarum ordines plerumque perturbant, et cum se inter equitum turmas insinuaverunt, ex essedis desiliunt et pedibus proeliantur. 2 Aurigae interim paulatim ex proelio excedunt atque ita currus conlocant ut, si illi a multitudine hostium premantur, expeditum ad quos receptum habeant. 3 Ita mobilitatem equitum, stabilitatem peditum in proeliis praestant, ac tantum usu cotidiano et exercitatione efficiunt uti in declivi ac praecipiti loco incitatos equos sustinere et brevi moderari ac flectere et per temonem percurrere et in iugo insistere et se inde in currus citissime recipere consuerint.

“This is the kind of fighting from chariots. At first, they ride around in all directions and throw spears and often, by the very frightfulness of the horses and the roar of the wheels, they shake the ranks [of the enemy] and, when they have slipped themselves among the troops of [enemy] cavalry, they leap from the chariots and fight on foot. Meanwhile, the charioteers move out a little way from the fighting and so place their vehicles that, if they [the dismounted fighters] should be pressed by a large number of the enemy, they may have an easy retreat to them. Thus, they provide the mobility of cavalry [as well as] the steadiness of infantry in [their] battles and they accomplish so much by daily practice and exercise that they are accustomed to control their stirred-up horses on a sloping and steep place and rein [them] in quickly and to turn [them] and to run along the yoke pole and to stand on the yoke and from there to take themselves back into the vehicles extremely speedily.” (Caesar, De Bello Gallico, Book IV, Chapter 33—my translation)

(Angus McBride)

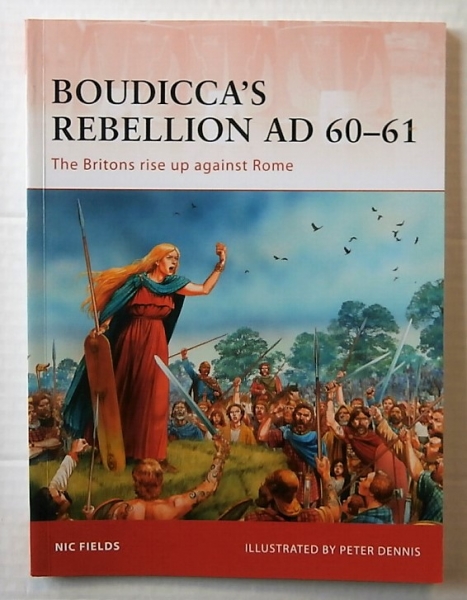

Tolkien may have remembered this from his schooldays, when he would first have encountered the text—and he might have found those wagons there, too, although slightly later. When, in 60-61AD, the Iceni queen, Boudica, led a revolt against Roman rule,

(Peter Dennis)

in the final battle, when the tribesmen advanced towards the Roman formation, as Tacitus (c.56-c.120AD) tells us, their families watched from their wagons, placed behind the battle line (De Vita et Moribus Iulii Agricolae, Chapter 34). And, as a prelude to the battle, Boudica had ridden among the ranks in a chariot (Chapter 35).

(another Peter Dennis—in fact, if you’d like to know more about this amazing woman, who, for a brief time, had been a real threat to the Romans, you might invest in:

And so, as in combining Anglo-Saxon and Norman to create the Rohirrim, Tolkien may have taken Steppe people, added Celtic Britons, and produced the Wainriders.

Thanks, as always for reading.

Stay well,

Remember that a horse will drink, on average, between 5 and 10 gallons (19-38 litres) of water a day,

And remember, as well, that there’s always

MTCIDC

O