Tags

Edoras, Fords of Isen, Ghan Buri Ghan, Helm's Deep, Isengard, Osgiliath, Rammas Echor, Rocky Road to Dublin, Stephen Dedalus, Stonewain Valley, Tharbad, Ulysses

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

“While in the merry month of May, from me home I started

Left the girls of Tuam so sad and broken hearted

Saluted father dear, kissed me darling mother

Drank a pint of beer, me grief and tears to smother

Then off to reap the corn, leave where I was born

Cut a stout black thorn to banish ghosts and goblins

Bought a pair of brogues rattling o’er the bogs

And fright’ning all the dogs on the rocky road to Dublin”

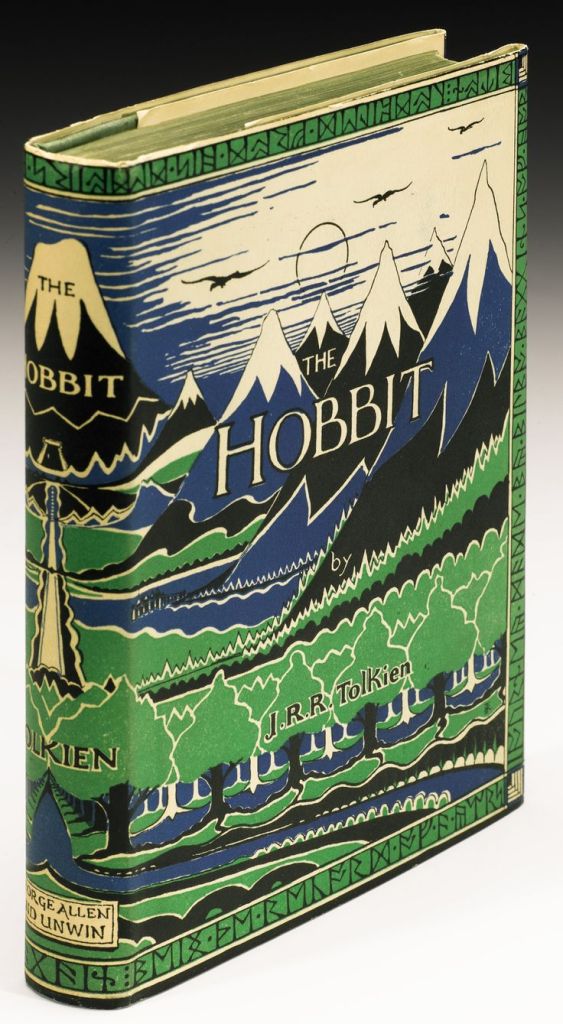

Another road song—this time an Irish one—and we’ll be continuing, in this posting, to follow the roads of Middle-earth, rocky and otherwise.

(This is a very catchy song and you can read the whole lyric here: https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/dubliners/rockyroadtodublin.html (although you’ll notice a couple of small discrepancies between the written lyric and the sung one) before you listen to Liam Clancy and Tommy Makem performing it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vb2Xw424W0M&list=RDVb2Xw424W0M&start_radio=1 For something about the history of the song, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rocky_Road_to_Dublin )

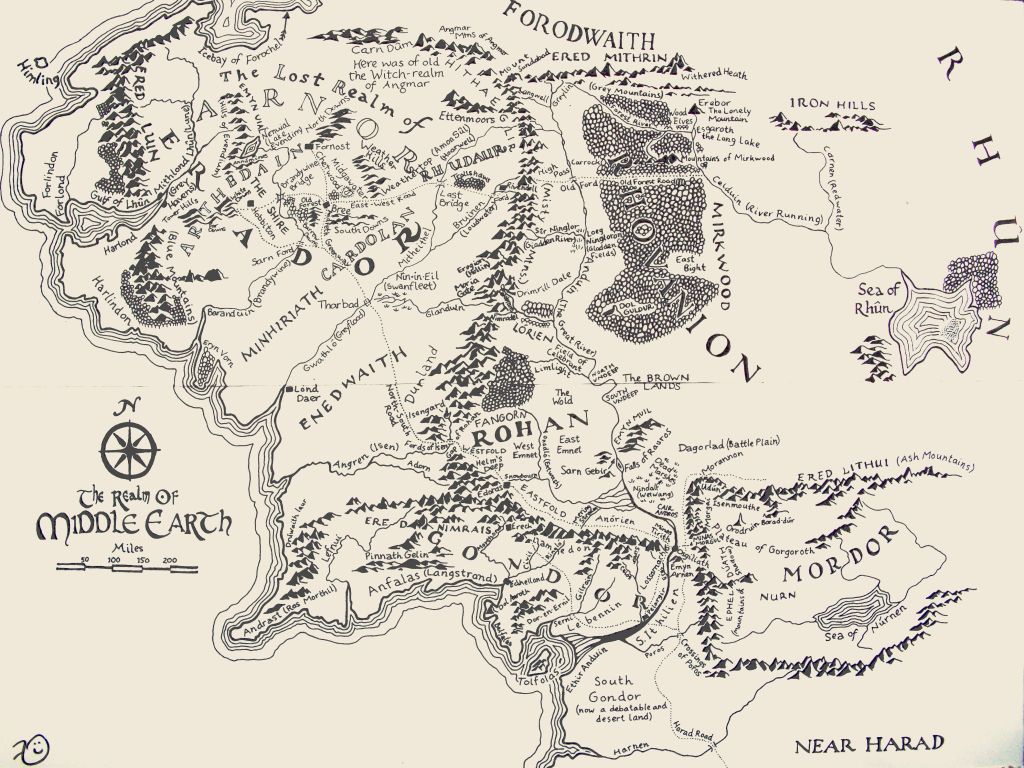

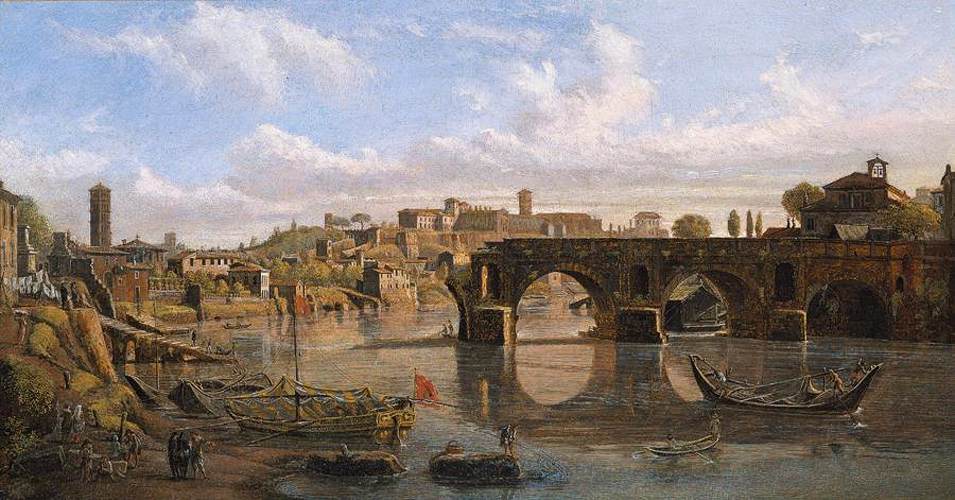

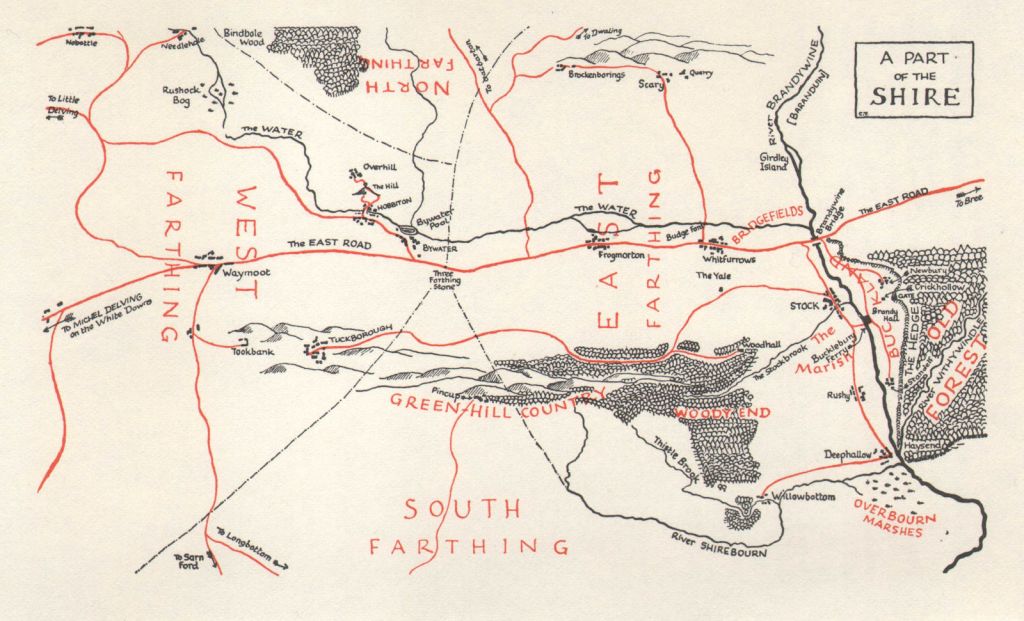

We had stopped our exploration at the ruined bridge at Tharbad—

(the so-called Ponte Rotto (“Ruined Bridge”) in Rome—actually the Pons Aemilius—here’s a very interesting article about it and other bridges in Rome: https://www.througheternity.com/en/blog/hidden-sights/rome-most-beautiful-historic-bridges.html )

Tharbad had once been a Numenorean city, with an impressive bridge which spanned the River Gwathlo (“Greyflood”), but

“A considerable garrison of soldiers, mariners and engineers had been kept there until the seventeenth century of the Third Age. But from then onwards the region fell quickly into decay; and long before the time of The Lord of the Rings had gone back into wild fenlands. When Boromir made his great journey from Gondor to Rivendell…the North-South Road no longer existed except for the crumbling remains of the causeways, by which a hazardous approach to Tharbad might be achieved, only to find ruins on dwindling mounds, and a dangerous ford formed by the ruins of the bridge…” (JRRT/Christopher Tolkien, Unfinished Tales, 277)

I wonder whether, when thinking of ruins, Tolkien had in mind the towns of southern Belgium destroyed by German shelling in the Great War, such as Ypres, which he would have walked through in 1916–

The road south from Tharbad, then, we can presume, was more like the Greenway farther north—grassgrown and abandoned.

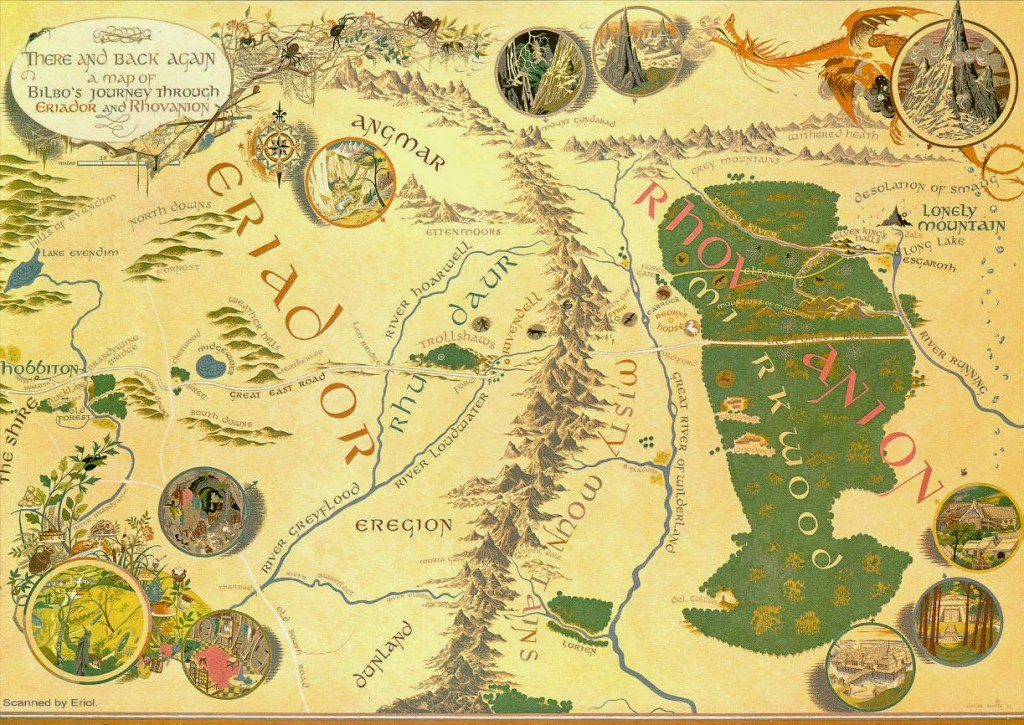

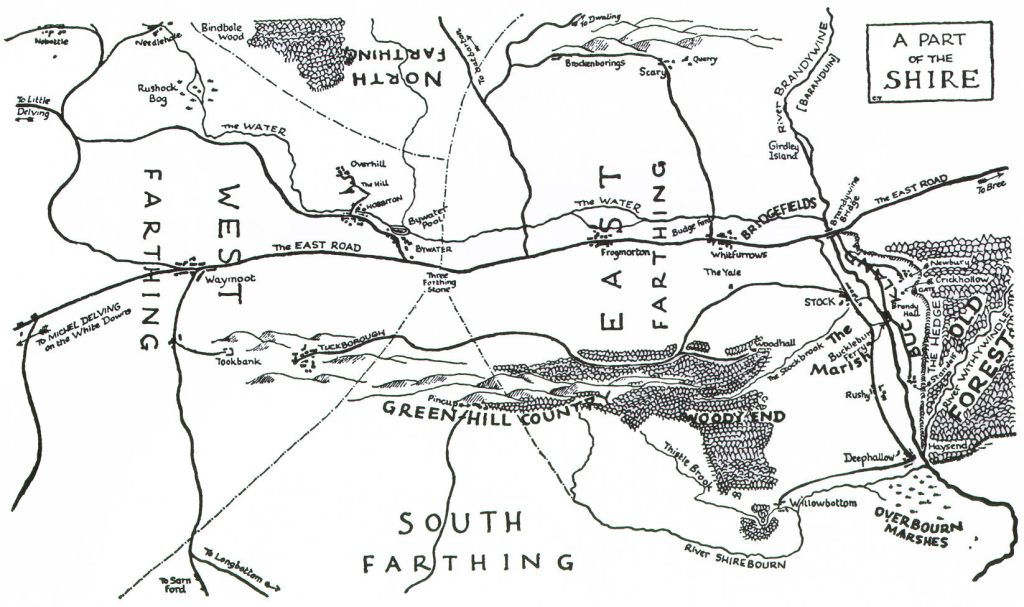

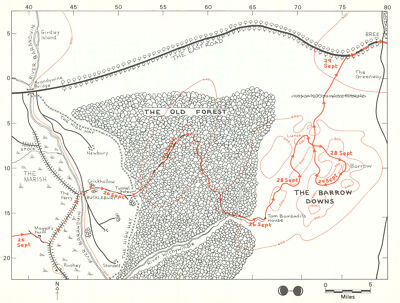

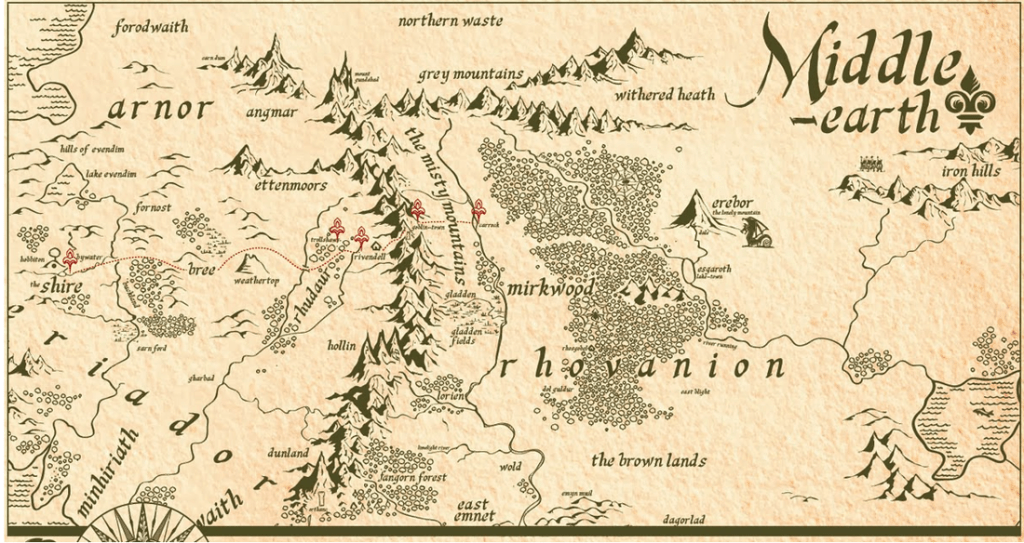

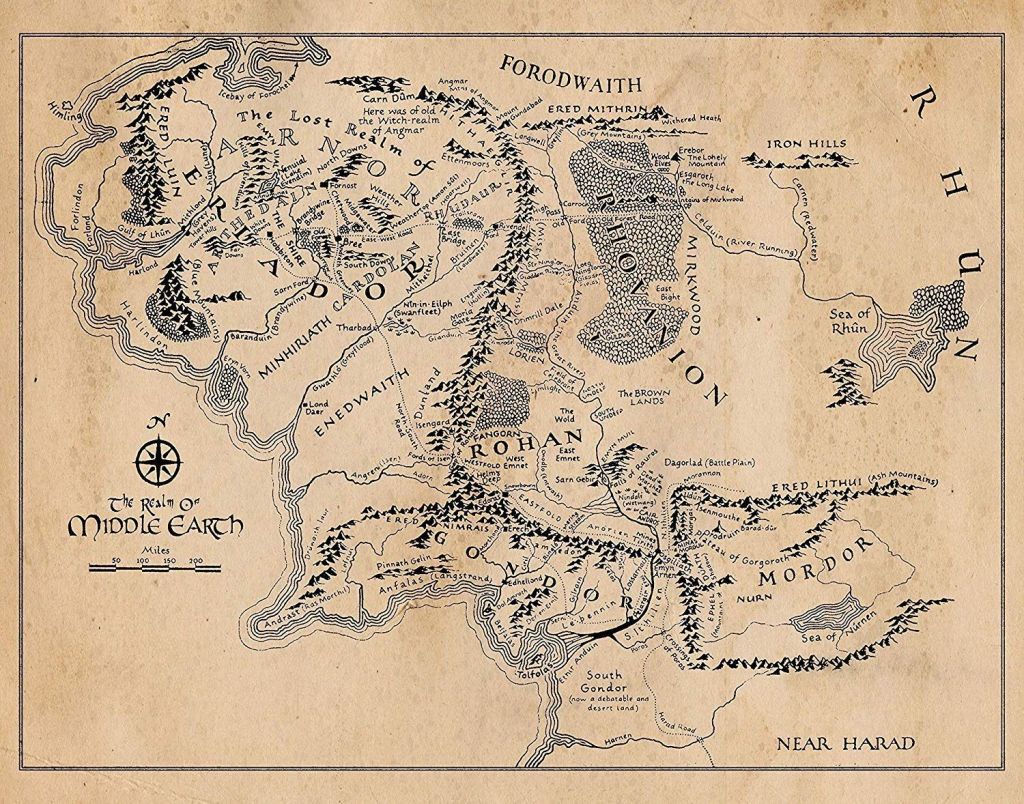

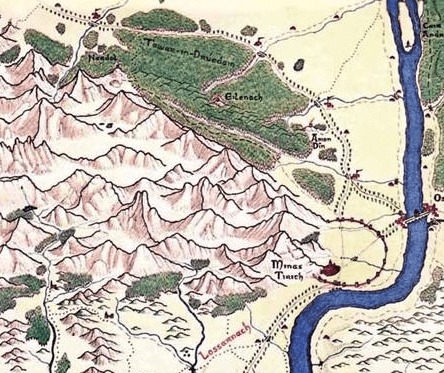

Using our map, we can see that the old road traveled through the Gap of Rohan,

(both this and the map above are derived, ultimately, from the Tolkiens’ map, but I haven’t seen this credited to anyone)

with Isengard off to its left,

(the Hildebrandts)

and, farther on, Helm’s Deep to its right,

(JRRT)

although I doubt that either was visible from the road, Isengard in particular being up the valley of the Isen.

JRRT has left us a useful description of the Fords of the Isen—

“There the river was broad and shallow, passing in two arms about a large eyot [from Old English, igeoth, “small island”], over a stony shelf covered with stones and pebbles brought down from the north.” (Unfinished Tales, 372—there is a long and detailed account here, 372-390, including the heroic death of Theodred, son of Theoden. This fills in the period when members of the Fellowship come to the defense of Helm’s Deep and Gandalf is abroad, looking for aid, while Merry and Pippin are rallying the Ents.)

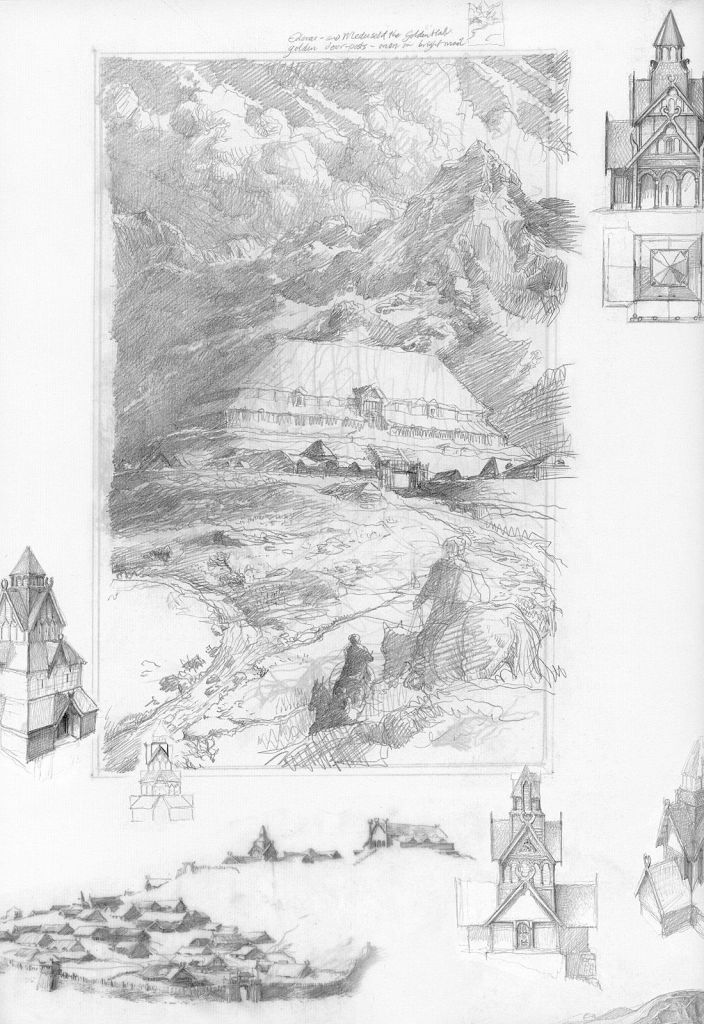

Down from Helm’s Deep would also be Edoras,

(Alan Lee—notice, by the way, that the usual image of the wall of Edoras isn’t the spindly palisade shown in the films, but a solid stone wall, of the sort JRRT must have meant when he wrote: “Following the winding way up the green shoulders of the hills, they came at last to the wide wind-swept walls and the gates of Edoras.” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 6, “The King of the Golden Hall”)

and the road to Gondor and Minas Tirith.

(Ted Nasmith)

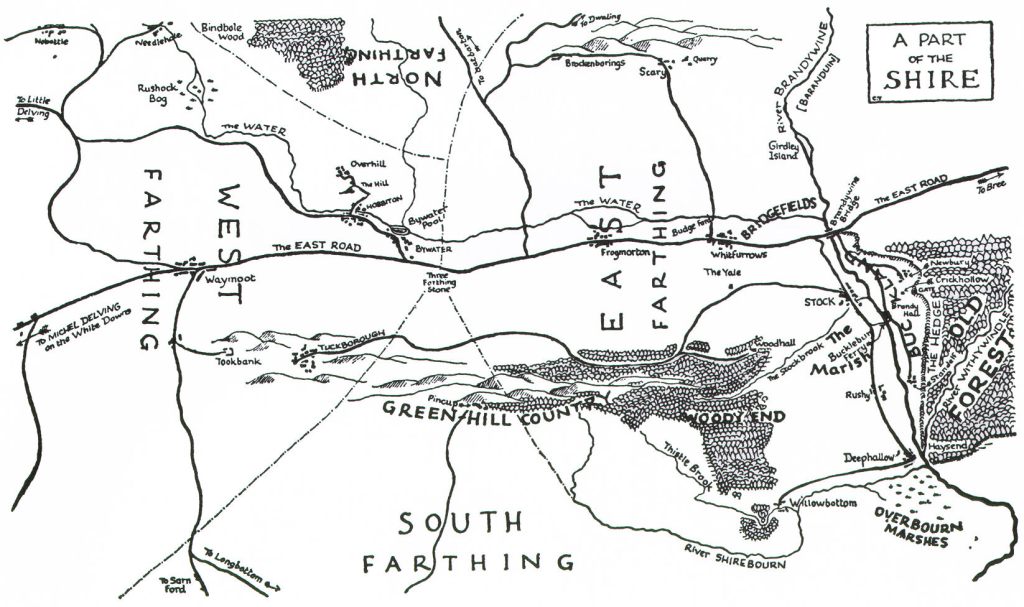

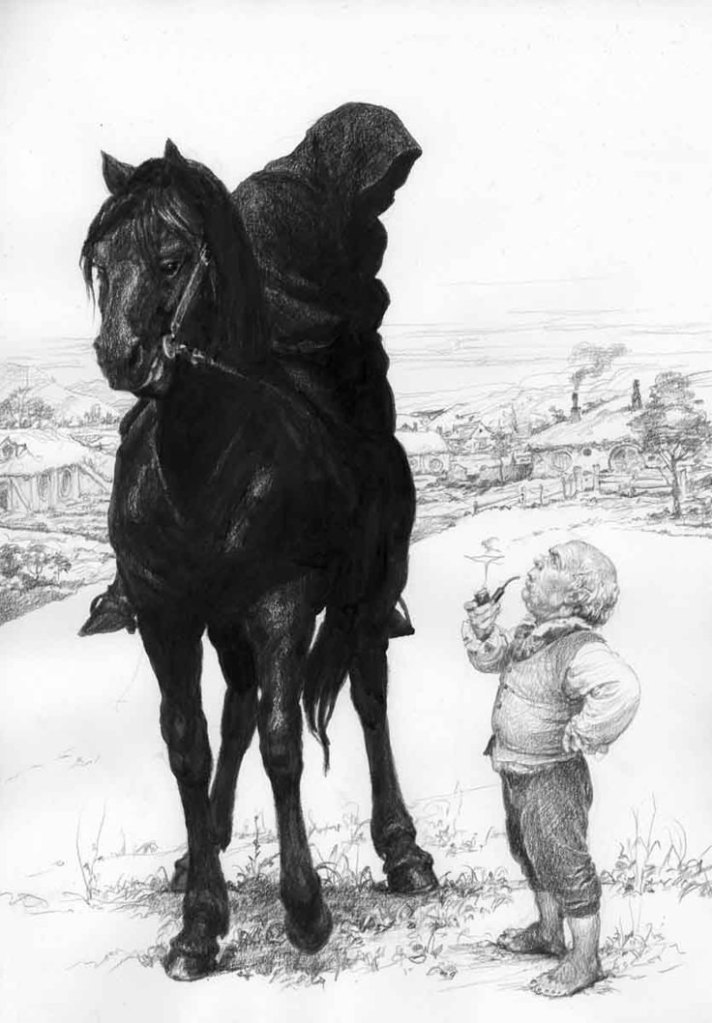

But we should pause here—as a hidden road will appear to our right—indicated to the Rohirrim in their ride south to the rescue of Minas Tirith by Ghan Buri Ghan, chief of the Woses (aka Wild Men—descendants of pre-Numorean settlers of Gondor).

(Hildebrandts)

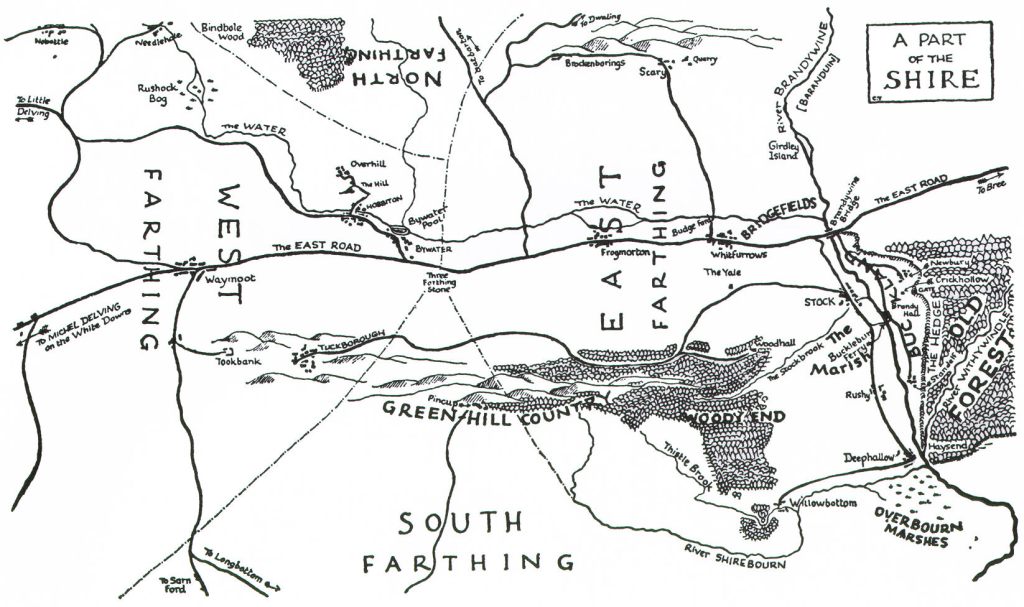

(This is taken from a large and elegant map which you can see here: https://i.pinimg.com/originals/70/bc/b6/70bcb6ccc3a0ed5068d6ce15fb5a09a4.jpg )

As he describes it:

“ ‘Road is forgotten, but not by Wild Men. Over hill and behind hill it lies under grass and tree, there behind Rimmon and down to Din, and back at the end to Horse-men’s road…Way is wide for four horses in Stonewain Valley yonder…but narrow at beginning and at end. Wild Man could walk from here to Din between sunrise and noon.’ ” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 5, “The Ride of the Rohirrim”)

And the narrator continues:

“It was late in the afternoon when the leaders came to wide grey thickets stretching beyond the eastward side of Amon Din, and masking a great gap in the line of hills that from Nardol to Din ran east and west. Through the gap the forgotten wain-road long ago had run down, back into the main horse-way from the City through Anorien; but now for many lives of men trees had had their way with it, and it had vanished, broken and buried under the leaves of uncounted years.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 5, “The Ride of the Rohirrim”)

A “wain” is a wagon

(This is the center of John Constable’s “The Hay Wain”, 1824, but it can give you an idea of what JRRT had in mind—picture this loaded with building stone instead of hay.)

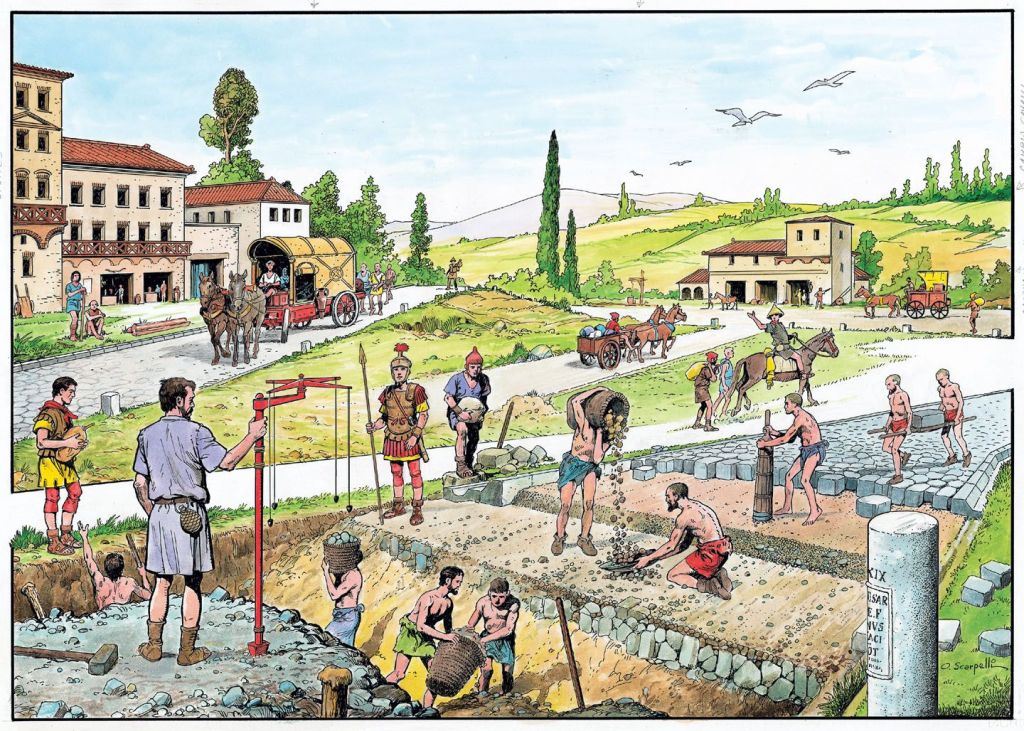

and it’s clear that what we’re seeing here is an old quarry road, which led from stone quarries down to Minas Tirith, to build its walls.

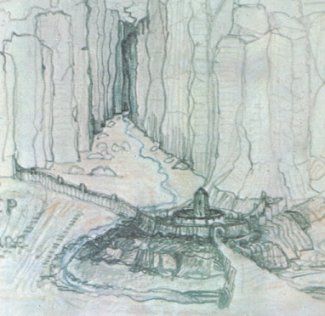

But, speaking of walls, we’re about to come up against one: the Rammas Echor, or great circuit of wall that surrounded the Pelennor:

(from the Encyclopedia of Arda site)

“Many tall men heavily cloaked stood beside him, and behind them in the mist loomed a wall of stone. Partly ruinous it seemed, but already before the night was passed the sound of hurried labour could be heard.”

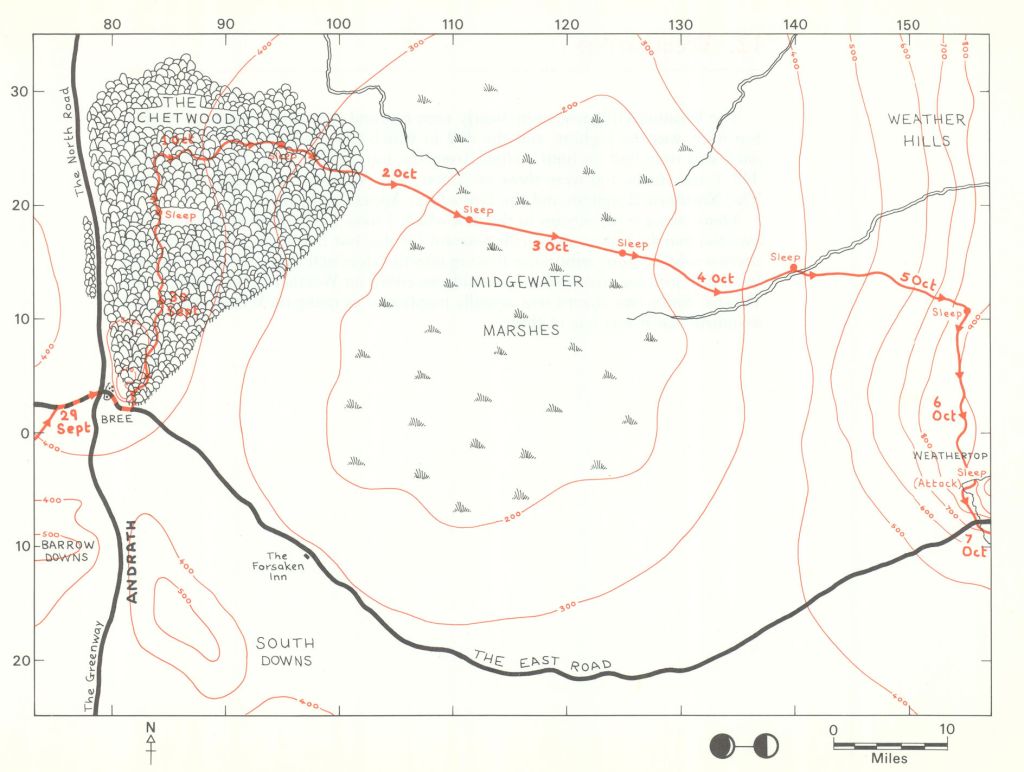

As you can see from the map, this was a very long wall (“For ten leagues or more it ran from the mountains’ feet and so back again…” — a standard for a league is about 3 miles, so the wall is about 30 miles—about 48km–long) , and I’ve always imagined it as looking rather like Hadrian’s Wall in northern England, some 80+ miles long (about 129km), as it appeared when finished.

There were larger gates in the area called the Causeway Forts, but there were clearly single, smaller gates as in the image above, as the text tells us: “…and the men made way for Shadowfax, and he passed through a narrow gate in the wall.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 1, “Minas Tirith”)

I suppose that we could circle around the wall, and then we’d have to get onto the causeway—that’s a kind of elevated road—

(This is the stone causeway leading to St.Michael’s Mount, in Cornwall, southwest England, with the tide coming in—or going out. You can read about St.Michael’s Mount here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Michael%27s_Mount )

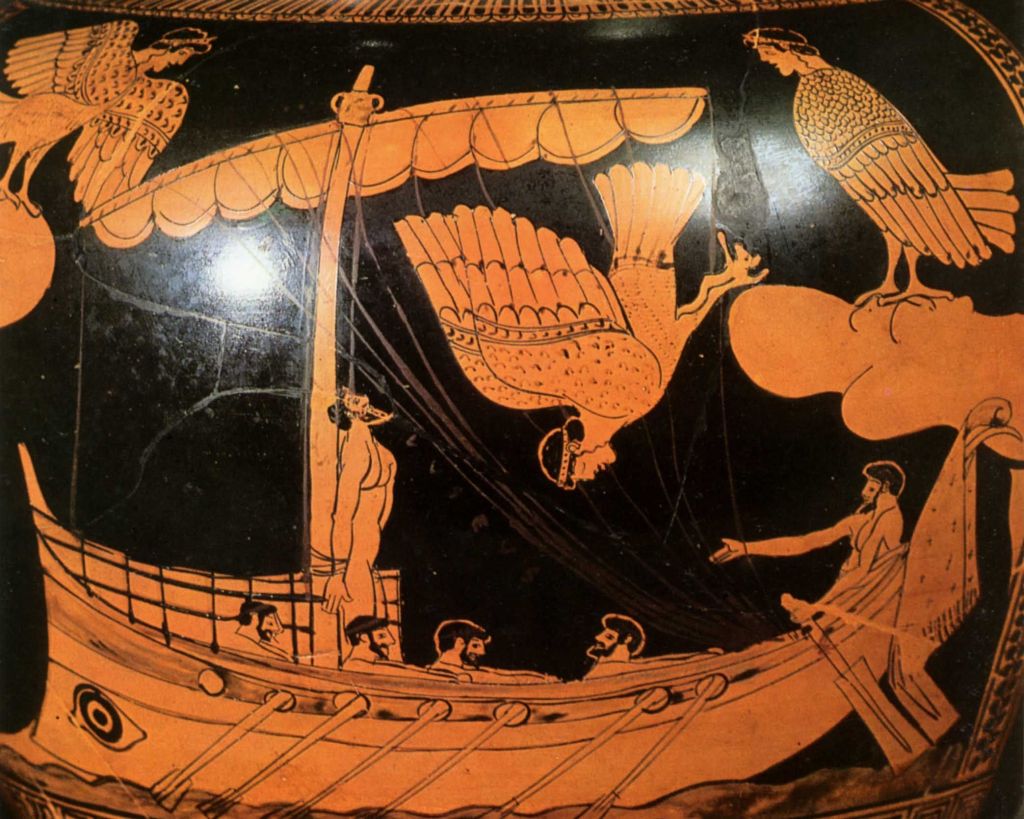

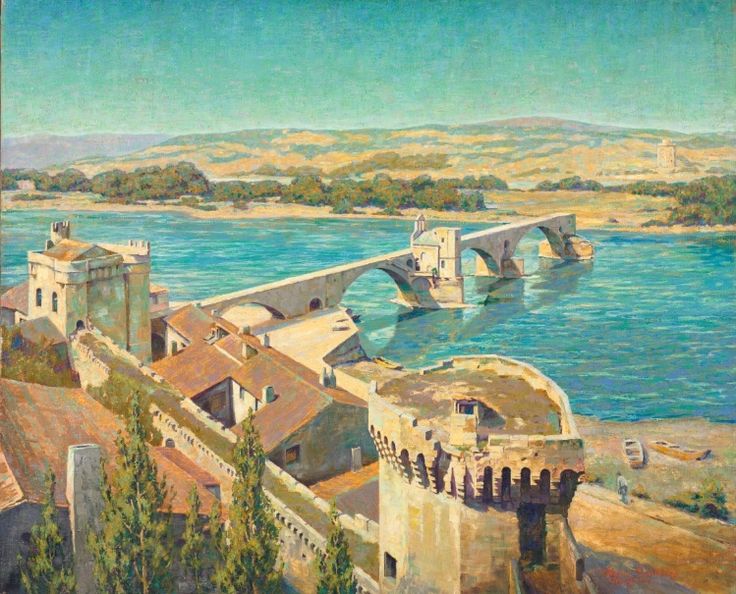

which leads to the ruined city of Osgiliath

where, alas, the bridges are broken (“And are not the bridges of Osgiliath broken down and all the landings held now by the Enemy?” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 8, “Farewell to Lorien “)

(Norris Rahming, 1886-1959)

and where we’ll stop for today, but pause at the site of one of those bridges in our next.

As ever, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

In James Joyce’s Ulysses, one of the main characters, Stephen Dedalus, calls a pier

a “disappointed bridge”—would you agree?

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O