Tags

A Child's Garden of Verses, Adelbert von Chamisso, Andrew Lang, Ausgabe des Fortunatus, Charles Perrault, Fortunatus' fortune-bag, Histoires ou Contes du Temps Passe, J.M. Barrie, Le Petit Poucet, Lord Dunsany, Peter Pan, Peter Schlemihl, Peter Schlemihls Wundersame Geschichte, Robert Louis Stevenson, seven-league boots, Shadow, Siglo de Oro, Sortes Tolkienses, The Charwoman's Shadow, The Grey Fairy Book, The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

We were practicing our sortes tolkienses (one way of finding a topic—by simply slipping a finger into The Lord of the Rings and opening it at that page—it’s not 100% useful, but sometimes…) and came upon the title of Chapter 2 of Book One of The Fellowship of the Ring: “The Shadow of the Past”.

In the context of the chapter, we see that that shadow is cast by the history of the Ring itself and also by its maker, Sauron. That, in turn, set us off on thinking about literary shadows…

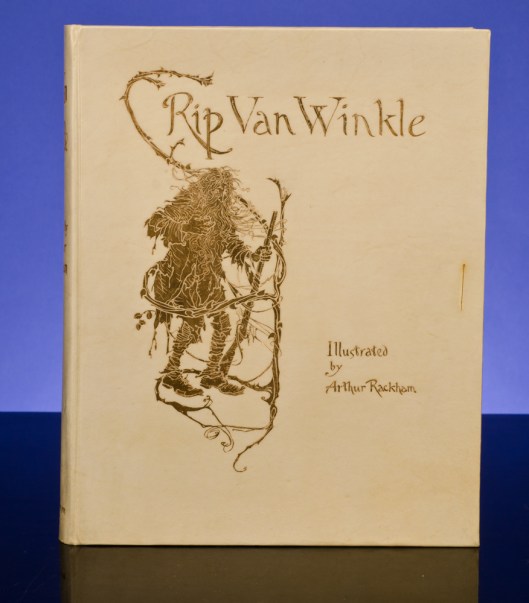

In 1885, Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894)

published a collection of poems.

Poem #19 (if you count the dedication, which is, in fact, a poem) begins:

“I have a little shadow that goes in and out with me,

And what can be the use of him is more than I can see.”

[If you would like your own copy of this volume, follow this LINK.]

In fact, in literature, its use is both visible—and invisible.

In psychology, the shadow is metaphorical, being used to symbolize an unconscious part of the personality. [For more on this, see this LINK.]

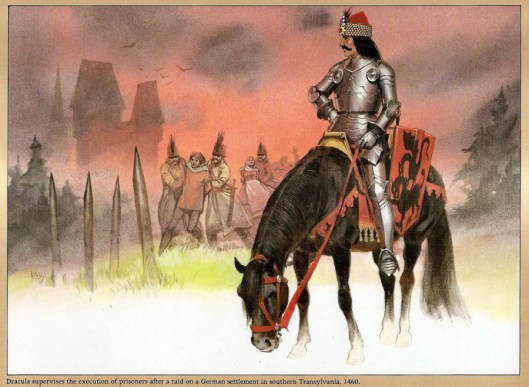

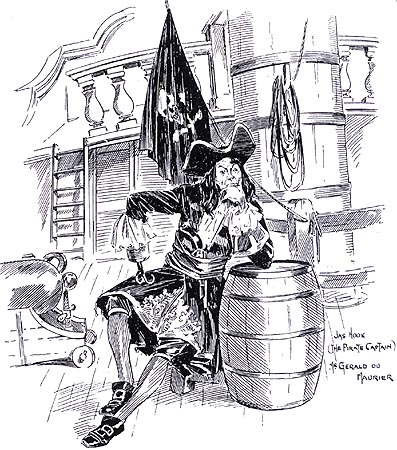

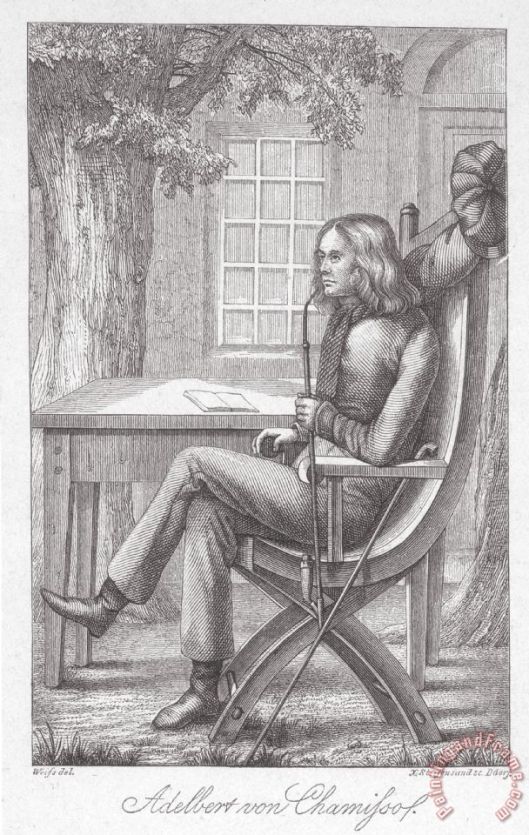

And, visibly—but also invisibly—the shadow as physical object can represent something more, as we find in perhaps the first modern literary use of the shadow in Adelbert von Chamisso’s (1781-1838)

novella (a short novel), Peter Schlemihls Wundersame Geschichte (1814), “Peter Schlemihl’s Amazing Story”.

Here’s the first English translation, from 1824.

In the story, the protagonist, Peter Schlemihl, meets a strange man, who can pull anything out of his pocket—and we mean anything. As Schlemihl reports:

“If my mind was confused, nay terrified, with these proceedings, how was I overpowered when the next-breathed wish brought from his pocket three riding horses. I tell you, three great and noble steeds, with saddles and appurtenances! Imagine for a moment, I pray you, three saddled horses from the same pocket which had before produced a pocket-book, a telescope, an ornamented carpet twenty paces long and ten broad, a pleasure-tent of the same size, with bars and iron-work!”

(This is from the 3rd edition (1861) of that first English translation.)

Impressed, Schlemihl is quickly persuaded to make a trade. The strange man offers him a magic purse, which he calls “Fortunatus’ fortune-bag”. This object is based on an old story which seems to appear for the first time in 1509 as Ausgabe des Fortunatus (the “Edition/Issue of Fortunatus”?), in which Fortunatus (as you’ll probably guess, the name means “Lucky”) has both a wishing cap and this bag. Here’s the title page of that first edition.

[If you would like to read one version of the Fortunatus story, here is a link to it from Andrew Lang’s The Grey Fairy Book (1900).]

The purse will always produce ten gold coins when one puts a hand inside, guaranteeing a steady means of wealth for the owner. In return for this, Schlemihl hands over–his shadow.

This seems an odd trade, but having a magic bag which acts as an endless bank account is certainly no less strange. Not to be too literal-minded, but beyond the idea that a shadow is a tradable item, it makes us wonder, however: what could a shadow be made of that it can be removed and collected?

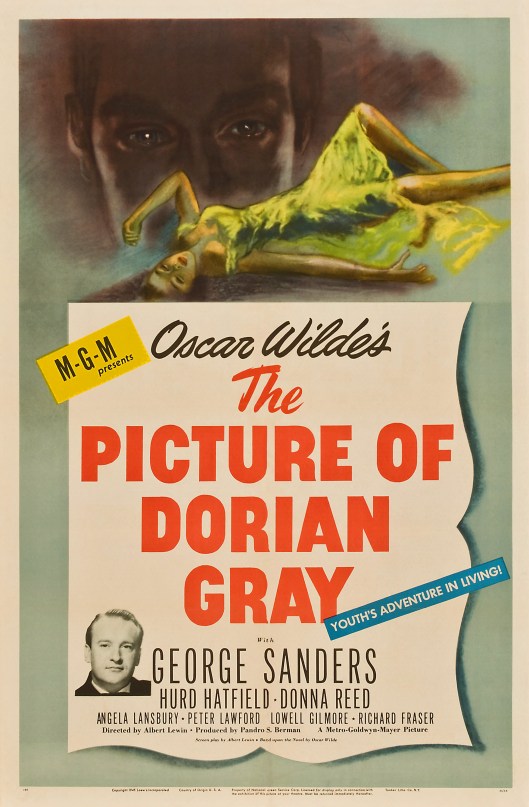

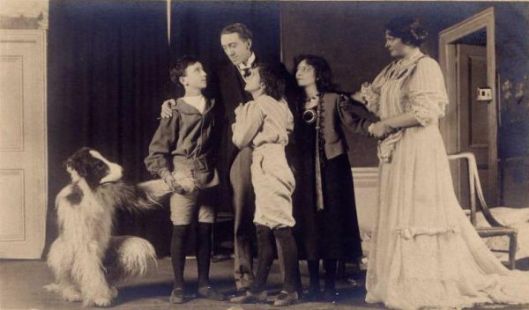

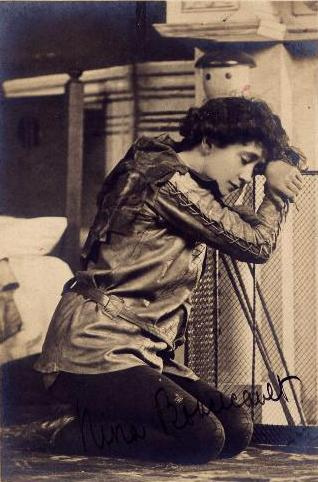

At the beginning of Peter Pan (1904), Peter has lost his shadow and Wendy reattaches it by sewing it on, as if it were simply mobile black cloth and perhaps this is how we might think about it as a physical object, at least for shadow stories.

Although he is pleased with the money, Schlemihl soon realizes the real price he has paid: when people see that he has no shadow, they avoid him in anything from disgust to horror, which ruins his ability to live anywhere and even to marry the girl he wishes. The shadow, then, is more than cloth: it is part of a person’s identity. If you cast no shadow, you are not quite human. The real price of the shadow is even higher, however, as Schlemihl learns when the strange man (who is obviously Satan in human form) returns to offer a second bargain: the Devil will return his shadow in return for his soul.

It’s clear that here Schlemihl has learned his lesson, refusing this offer several times and finally throwing away the “fortune-bag”. Although he may believe that he is done with magic, magic is not yet done with him, however. With some of the few coins remaining to him, by accident (or so it seems), he buys a pair of seven-league boots. (A “league”, classically, is about three miles, so, when he puts them on, each step he takes is at least twenty-one miles.)

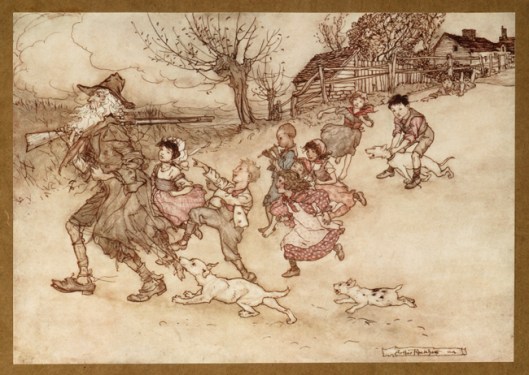

This element of the story, in turn, is also based on something in another older story, which appears in Charles Perrault’s (1628-1703)

1697 collection, Histoires ou Contes du Temps Passe,

“Le Petit Poucet” (maybe “Thumblet”?). In this story, a character steals a pair of these boots from a pursuing ogre, allowing the thief to cover great distances with every stride.

[If you’d like to read this story, here’s a LINK from a 1901 translation.]

With these boots, Schlemihl never regains his shadow, but eventually gains a peaceful existence studying the natural world (which, in fact, von Chamisso did, as well, becoming a well-known naturalist later in life).

[Here’s a LINK to a translation of the story by Michael Haldane.]

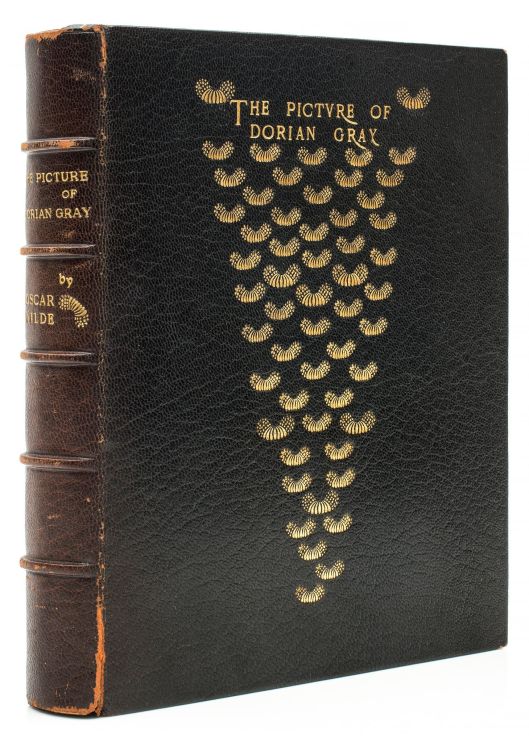

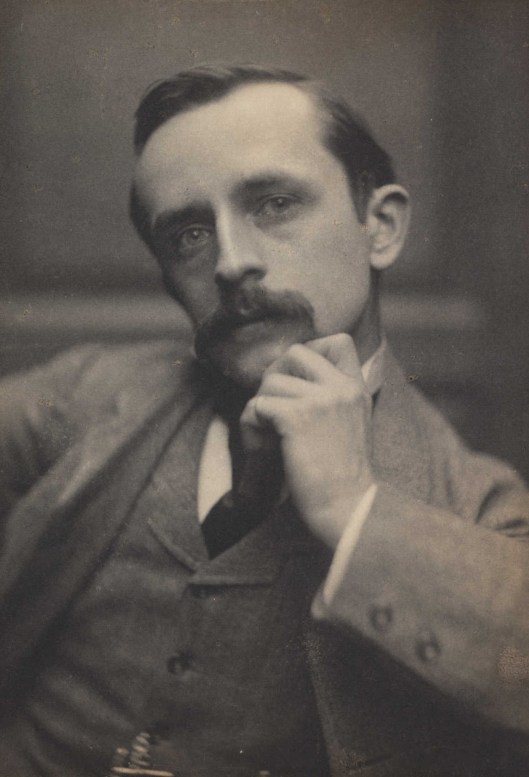

More than a century later, the early modern fantasy writer, Lord Dunsany (1878-1957)

reused the idea of buying or trading shadows in his 1926 novel, The Charwoman’s Shadow.

A charwoman, or, simply, “char” (“char” is the same as “chore”, meaning “a task”), in the UK means a kind of cleaning woman.

When it comes to fantasies, the idea that this may be about the shadow not of a princess, or at least a lady in distress, but of an ordinary cleaning lady, is immediately intriguing, but the charwoman isn’t really the main character. That’s Ramon, the son of an impoverished Spanish nobleman.

To earn money for his sister’s dowry, as well as to find a profession, Ramon apprentices himself to a wizard who deals, among other things, in shadows. As payment for his learning, Ramon uses his shadow—but, just like Peter Schlemihl before him, quickly comes to regret it. The charwoman works in the wizard’s house and, as Ramon slowly learns spells, he also learns her story and what has happened to her since she traded away her shadow long before.

In a moment of chivalry (the story takes place in Spain in what’s called the Siglo de Oro, the “Golden Century”—the early 16th to the later 17th centuries–when wealth from the New World made Spain a world power, as well as a leader in the arts), Ramon promises to rescue the Charwoman’s shadow for her. In the house of a wizard, you can imagine that this won’t be easy, but, eventually, and through ingenuity, he does so, only to discover that—but you should really read the story for yourself.

[Unfortunately, as this book was published in 1926, it’s still under copyright here in the US, so we can’t offer our usual LINK, but we can offer you Peter and Wendy (1911), the novel version of Barrie’s 1904 play—LINK.]

In contrast to shadows which can be traded or lost, what’s interesting to us about Sauron’s shadow is that it’s no more than a suggestion of the appearance of its owner, who, although he casts that shadow over all of Middle-earth, never appears physically in the novel. The Nazgul—shadowy figures themselves—represent him, but Sauron himself is never more than a shadow and, in fact, when he is eventually destroyed, it’s his shadow we see broken and swept away:

“And as the Captains gazed south to the Land of Mordor, it seemed to them that, black against the pall of cloud, there rose a huge shape of shadow, impenetrable, lightning-crowned, filling all the sky. Enormous it reared above the world, and stretched out towards them a vast threatening hand, terrible but impotent: for even as it leaned over them, a great wind took it, and it was all blown away, and passed; and then a hush fell.” (The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 4, “The Field of Cormallen”)

That “little shadow”, then, certainly has more uses than the child in Stevenson’s poem will ever see.

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD