Tags

Anduril, arthur-hughes, bent-swords, Fafnir, George Macdonald, Glamdring, Goblins, great-goblin, Howard Pyle, King Edward's Horse, NC Wyeth, Orcrist, Scimitar, Sigurd, Sigurd Portal, swords, The Hobbit, Tolkien, William Morris

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

Every time I read or teach The Hobbit, I come to this passage:

“There in the shadows on a large flat stone sat a tremendous goblin with a huge head, and armed goblins were standing round him carrying the axes and the bent swords which they use.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 4, “Over Hill and Under Hill”)

and I wonder: what does Tolkien mean by “bent swords”?

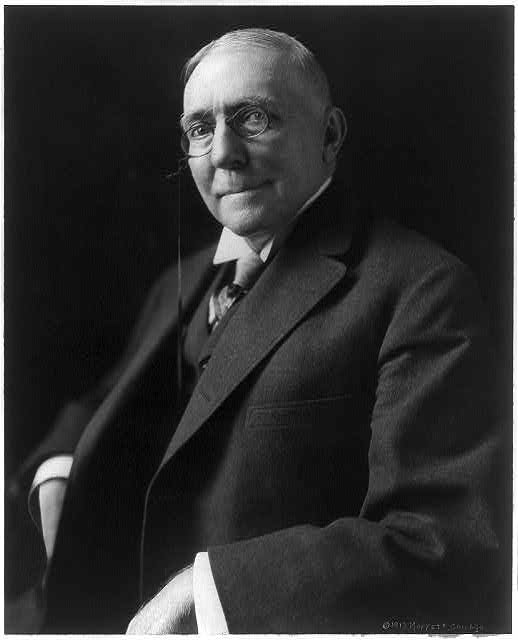

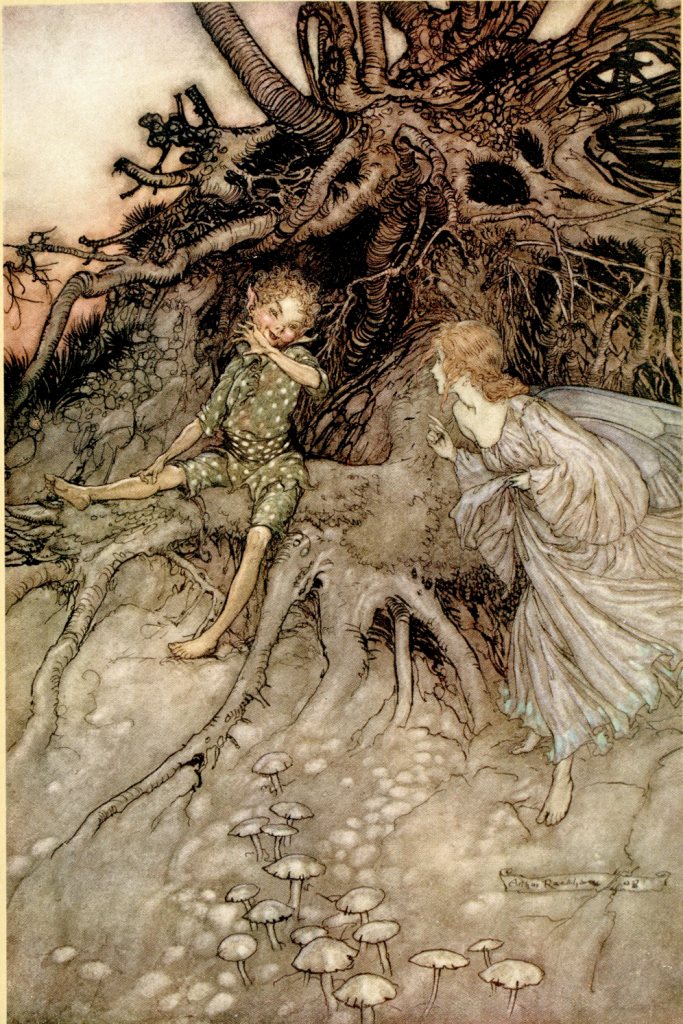

As a medievalist, and as someone who grew up in the world of illustrators like Howard Pyle (1853-1911)

and NC Wyeth (1882-1945),

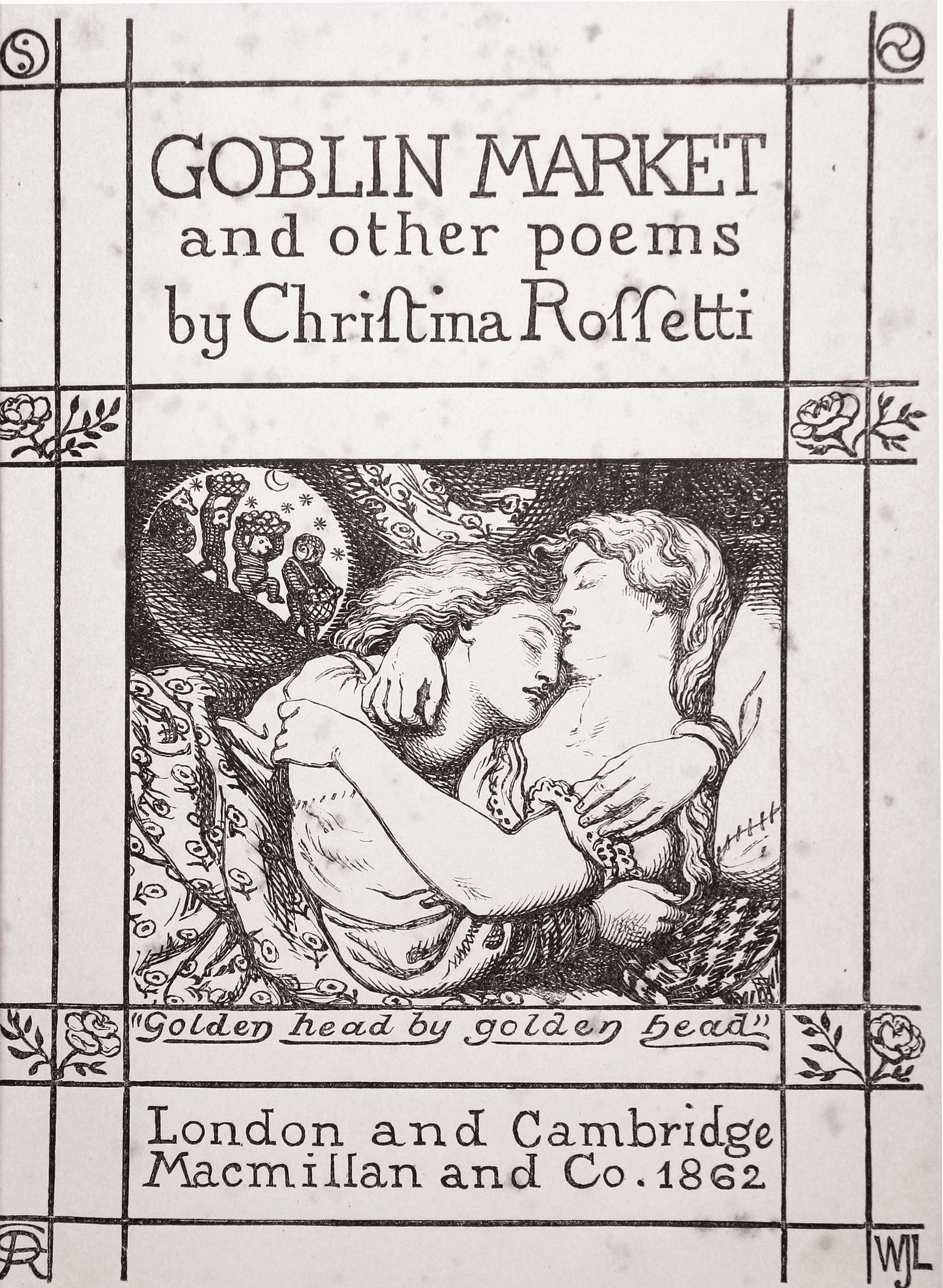

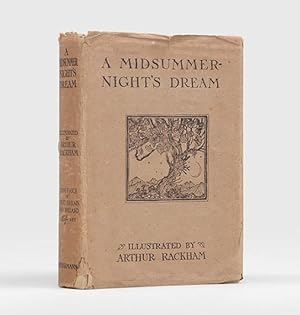

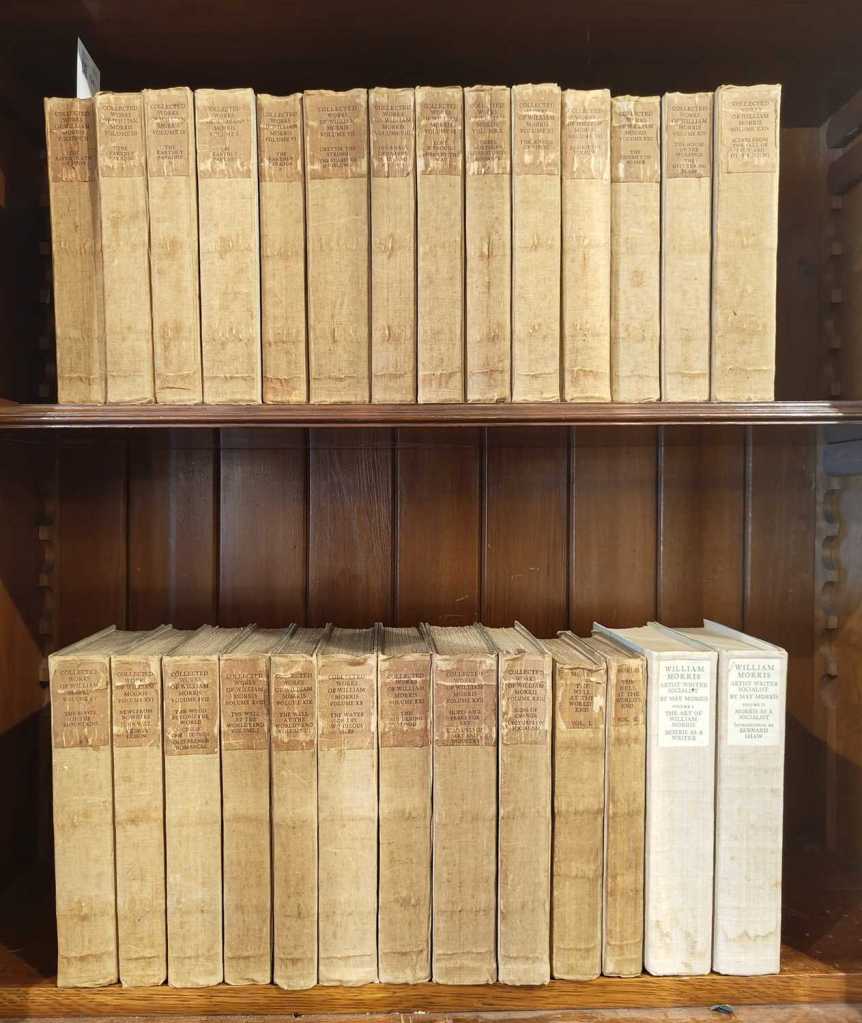

as well as an avid reader of the stories of William Morris (1834-1896),

it’s not surprising that Tolkien’s works so often include swords, although perhaps the first sword he met may have been in Andrew Lang’s (1844-1912) The Red Fairy Book, 1890, where, in the last chapter, he would have found Sigurd and a, to us, strangely-familiar sword—

“ONCE upon a time there was a King in the North who had won many wars, but now he was old. Yet he took a new wife, and then another Prince, who wanted to have married her, came up against him with a great army. The old King went out and fought bravely, but at last his sword broke, and he was wounded and his men fled. But in the night, when the battle was over, his young wife came out and searched for him among the slain, and at last she found him, and asked whether he might be healed. But he said ‘ No,’ his luck was gone, his sword was broken, and he must die. And he told her that she would have a son, and that son would be a great warrior, and would avenge him on the other King, his enemy. And he bade her keep the broken pieces of the sword, to make a new sword for his son, and that blade should be called Gram.” (“The Story of Sigurd”, 357 If you don’t have your own copy of Lang’s collection, here it is for you: https://archive.org/details/redfairybook00langiala/redfairybook00langiala/mode/2up courtesy of the invaluable Internet Archive. If you don’t know this source, and you enjoy this blog, you should check it out. It has the most remarkable things, even including a very good selection of silent films and film classics, like Kurosawa’s “The Seven Samurai”, 1954, which, for me—and for George Lucas—is a model for adventure films and you can see it here for free: https://archive.org/details/seven-samurai-1954_202402 )

Yes, “the sword that was broken”—Anduril—and Sigurd has it reforged—and uses it to kill Fafnir, the dragon.

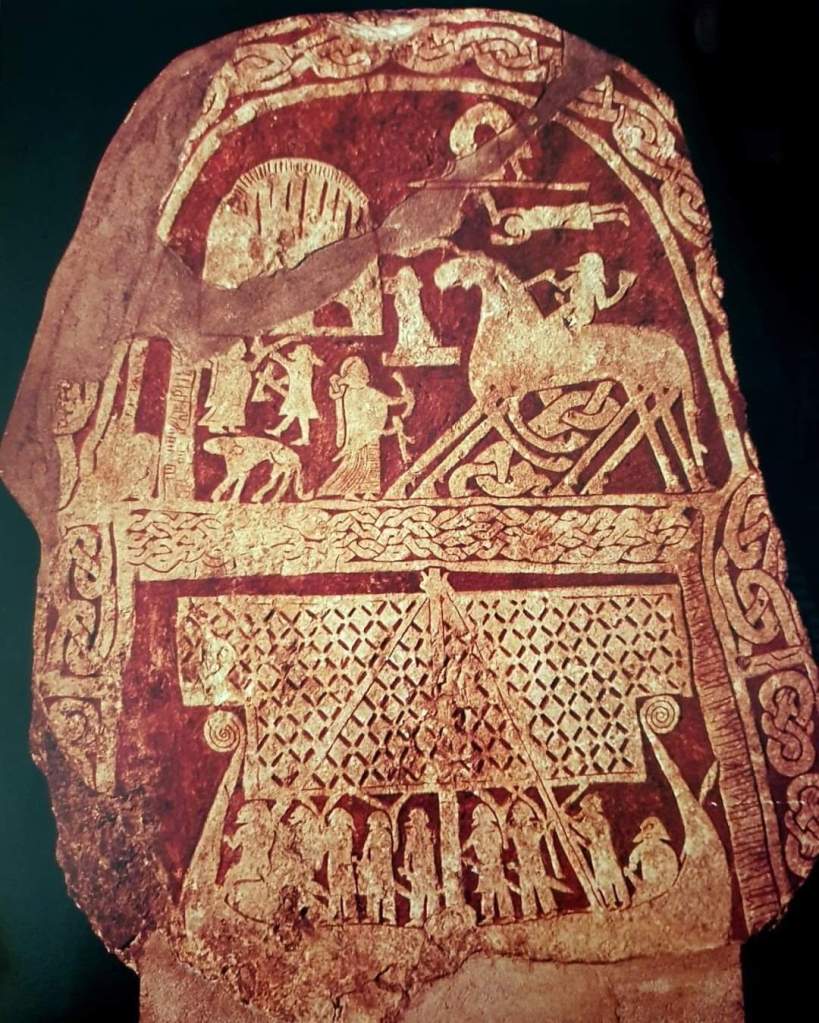

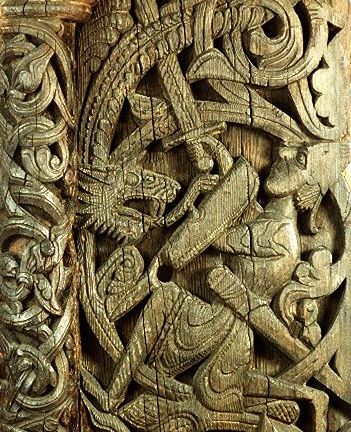

(This is from the “Sigurd Portal” of a lost stave—wooden—church from Hylestad, in Norway, dating c1200AD. Fortunately, the doorway carvings were saved and they show in detail the story of Sigurd. Here’s where you can read more: https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/sigurddoor.html#location and here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hylestad_stave_church )

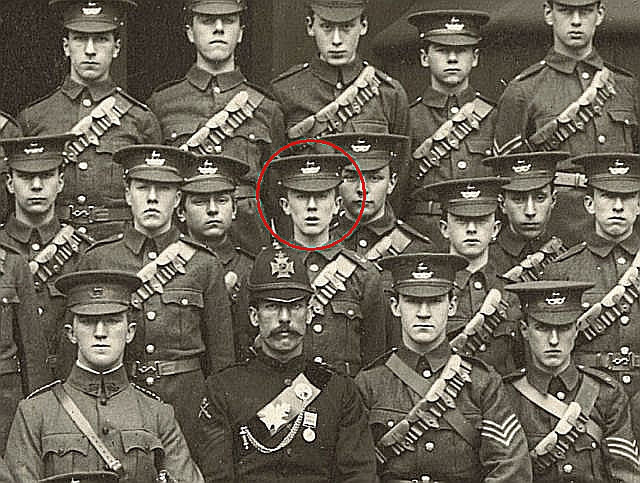

In his own life, Tolkien would have been personally familiar with swords. When he was a member, briefly, of King Edward’s Horse,

in 1912, he would have been issued with this, the Pattern 1908 cavalry sword.

To me, it’s rather a strange weapon, seemingly designed only to stab,

whereas earlier cavalry blades might be used both to stab and to slash (very useful in chasing off enemy infantry)

Then, a new 2nd lieutenant in 1915,

JRRT would have had to buy himself the Pattern 1897 infantry officer’s sword

(as there were an increasing number of new officers from families who couldn’t afford it, there was a kind of subscription created to help such officers acquire a required piece of equipment. For more on just what was required of officers, who had to provide their own kit, see Field Service Manual 1914, pages 16-18, here (and yes, again, it’s from the Internet Archive): https://archive.org/details/fieldservicemanu00greauoft/page/n11/mode/2up )

These, as you can see, are straight-bladed swords, however.

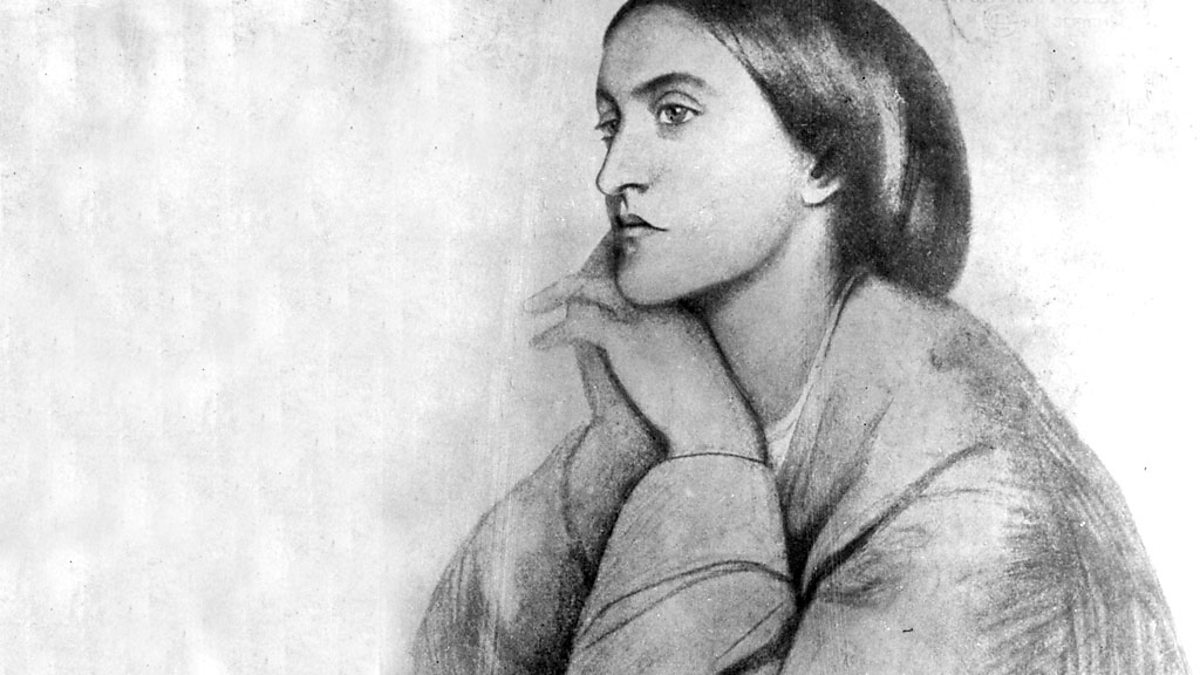

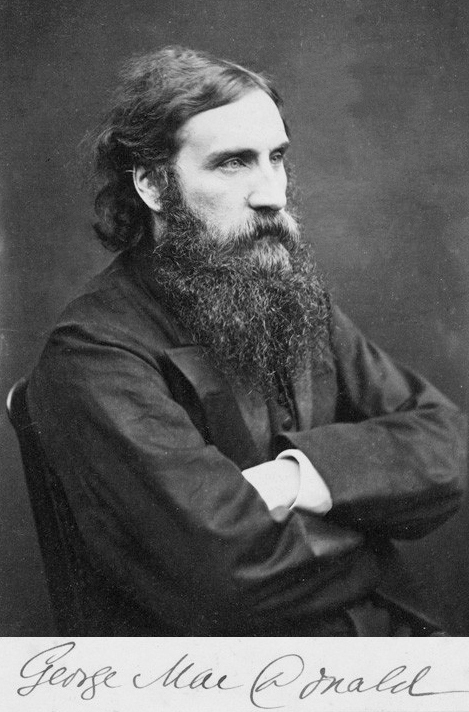

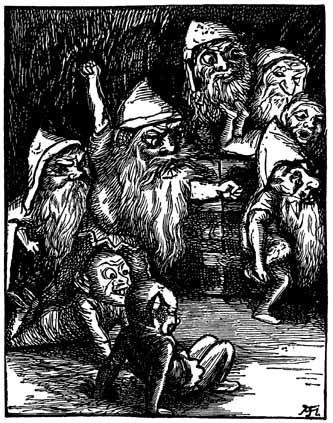

Tolkien’s earliest experience with goblins was probably with George MacDonald’s (1824-1905) The Princess and the Goblin (1871/2), and he likens his own later goblins/orcs to them (see Letters, 267, 279).

The illustrations are by Arthur Hughes (1832-1915) and, as far as I can see, there’s not a bent sword among them (If you don’t know the story, here’s the text, but without its original illustrations, alas: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/708/pg708-images.html )

If we try some Tolkien goblin illustrators, we find Justin Gerard’s version of the scene with the Great Goblin, where there are a few pole arms off to the left, but the only sword must be Orcrist.

(Justin Gerard—you can see more of his work here: https://www.artstation.com/justingerardillustration and here: https://www.justingerard.com/the-art-of-justin-gerard )

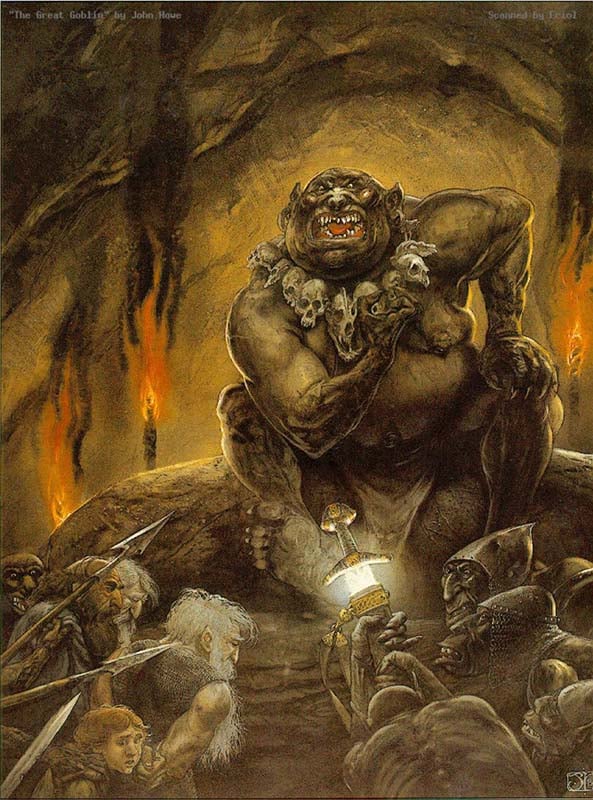

Here’s John Howe’s version of the scene—

with Orcrist peeking out of its scabbard and a straight sword and a couple of spears off to the left.

Then there’s Alan Lee’s, with the seemingly inevitable Orcrist, but with, just below it, perhaps a sabre—a curved sword

and we see this again in Lee’s depiction of Bilbo’s encounter with the goblin door guards.

In Michael Hague’s illustration for the escape from the Great Goblin’s throne room,

we see both Orcrist and Glamdring, along with one more seemingly curved sword.

Are any of these, however, an example of a “bent sword”? Archaeologists have discovered numerous ancient swords which appear to have been “sacrificed” by being bent–

but this is hardly what Tolkien meant. Then there is what might be taken literally for a “bent sword”—

from Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings, but I must say, this looks pretty improbable as a sword—if you see how the grip is shaped, that spike at the end if pointing upwards: what could it possibly be for? In fact, when one sees a chart of swords from the films, I’m not sure about many of them as useful weapons—

Those to the left share patterns with swords from our Middle-earth, both those on the right look like they might be dramatic over a fireplace, but I’d question their use as practical weapons.

So what might this “bent sword” be? Some of the swords in the illustrations above would suggest that their artists believed that, by “bent”, Tolkien meant “curved”. One possibility: we know that Tolkien had read or had read to him at least one of Andrew Lang’s fairy books (the Red Fairy Book, as mentioned above), but perhaps he had also seen Lang’s Arabian Nights Entertainments (1898) in which there are a number of illustrations with scimitars in them—

(Here’s a copy of the book for you: https://archive.org/details/arabiannightsent00lang/page/n9/mode/2up )

Scimitars are curved and, barring silly ones like those in Disney’s Aladdin—which look more like something used for carving meat–

are both deadly and would seem very exotic, if not alien,

in contrast to very medieval swords like Orcrist and Glamdring.

I doubt that we’ll ever know exactly what JRRT had in mind, but, if I had to illustrate “armed goblins…carrying axes and the bent swords…” I might consider drawing—in both senses—such blades.

Stay well,

Avoid inviting caves, even if Stone Giants are playing dodge ball outside,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

I’ve just discovered a contemporary illustrator who clearly enjoys the dramatic style of artists like Pyle and Wyeth, as well as French historical artists, like Meissonier (1815-1891). This is Ugo Pinson (1987-) and here is a sample of his work.

He has illustrated book covers as well as several graphic novels and done illustrations for the “Witcher” series. His sketches alone show his skill and talent. You can see more samples here: https://duckduckgo.com/?q=ugo+pinson&iar=images&iai=http%3A%2F%2Fbdzoom.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2016%2F07%2F13427953_10154226704759687_4371726455862878086_n.jpg