Tags

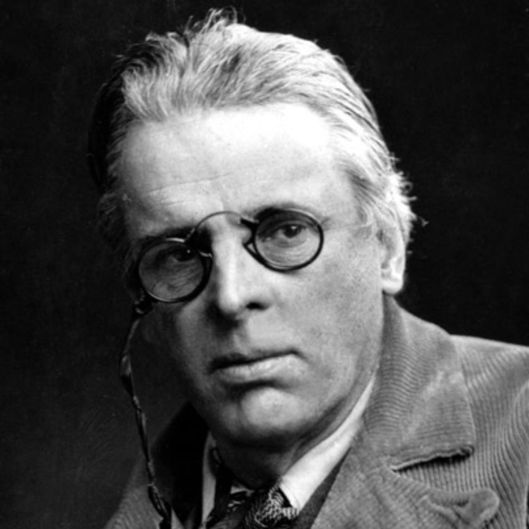

Apollonius, Aragorn, Argo, Blue Wizards, Denethor, Faramir, Gandalf and the Balrog, Grey Havens, Heracles, Hildebrandts, Hylas, Istari, Jason and the Golden Fleece, Merlin, Radaghast, sage, Saint Nicholas, Saruman, Sharkey, The Argonautica, The Fantastic Four, The Lord of the Rings, Theoden, Tiresias, Tolkien, Valar, W.B.Yeats

Dear readers, welcome, as always.

Recently, we wrote a posting about Saruman and his fate. It was fun to think about, but it made us think further about why Saruman, in the Shire, is called “Sharkey” by his thugs—supposedly from Orcish sharku, “Old Man”. If we had never read a description of Saruman, but only the nickname, we might think of “the old man” either as an older Anglo-American expression either for a father—“my old man keeps nagging me about cutting the grass, if I want my allowance” (note the use of the possessive “my”)—a naval/military term for commander—“the old man said that, on his ship, smoking would never be allowed again” (always without the possessive)—or older English for husband—“her old man is fooling around behind her back—I hope she turns around!” (again, with a possessive).

In fact, Saruman is, literally, an old man

—as are all five of the Istari, the wizards sent to Middle-earth by the Valar about the year 1000 of the Third Age. As JRRT says in a letter to Robert Murray, S.J. (there’s a surviving draft on pages 200-207 of The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien):

“They are actually emissaries from the True West, and so mediately from God, sent precisely to strengthen the resistance of the ‘good’, when the Valar become aware that the shadow of Sauron is taking shape again.” Letters, 207

He further explains their role:

“At this point in the fabulous history the purpose was precisely to limit and hinder their exhibition of ‘power’ on the physical plane, and so that they should do what they were primarily sent for: train, advise, instruct, arouse the hearts and minds of those threatened by Sauron to a resistance with their own strengths; and not just to do the job for them.” 202

JRRT could have chosen a different path, of course, and created a plot in which there was constant, open war between the wizards and Sauron, and there is mention of war of some sort, as, during the time of The Hobbit, the White Council drives “the Necromancer” out of Dol Goldur in the southern part of Mirkwood. It’s not said how, but no army is mentioned, so we presume that it was done by magic against magic (on the subject of magic, see JRRT in the letter previous to the one to Murray, Letters, 199-200).

We wonder if, in choosing to limit the wizards’ power, Tolkien made the same choice which Apollonius of Rhodes (3rd century BC) made in his version of the story of Jason and the Golden Fleece, The Argonautica. If you don’t know this story, the shortest way to explain it is to say that Jason’s wicked uncle has stolen the throne which rightfully belongs to Jason and, in an effort to make Jason disappear, his uncle has sent him off on what he hoped was a suicide mission. That mission was to bring back a magical golden fleece from the far side of the Black Sea (at the time, this would have been like a mission to Mars). To help him, Jason summons heroes from across the Greek world.

Unfortunately for Apollonius, the traditional story on which his epic is based had, over time, gradually come to include every hero from ancient Greece on Argo,

This means that Heracles had to be asked to join, but there is a big difficulty in including Heracles: he’s so powerful that he could do the job all by himself.

Apollonius was extremely scrupulous, as far as we can tell, in following tradition, so he finds a way out. He puts Heracles’ bff, Hylas, on board the ship, then, at a watering spot, has the boy lured away by some randy water nymphs.

When Heracles goes off to find the boy, the ship leaves without him and the problem is solved. (Although Apollonius chooses to ignore the fact that the ship is still absolutely crammed with the ancient equivalent of The Fantastic Four. We suppose that, for him, Heracles was the only really major hero.)

Thus, we can imagine that Tolkien, believing that he could create a more interesting (and longer?) story without too much magic, has, in general, limited the wizards not in their power, but in the use of it. (There are exceptions, of course—we immediately think of Gandalf and the Balrog, for instance.)

The wizards do not just have the shape of men, however, but old men—“Thus they appeared as ‘old’ sage figures” (Letters, 202).

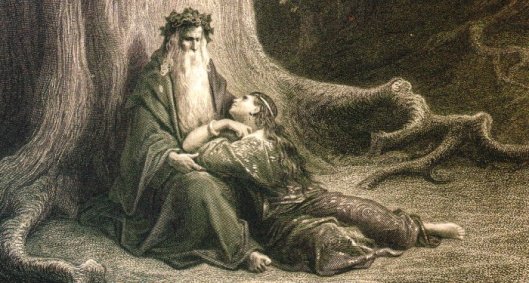

The word “sage” here is definitely one element in Tolkien’s choice for his characters. There is a world-wide tradition that old men are wise men—think of the ancient Greek seer Tiresias, for example—

or the Arthurian Merlin

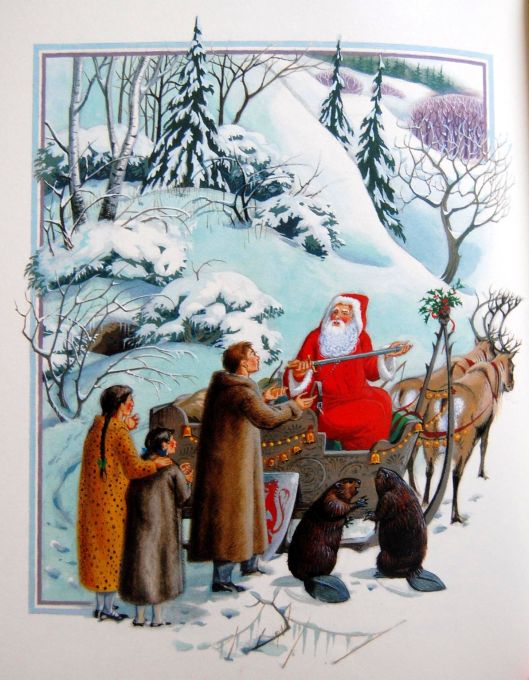

or Father Christmas/Santa Claus.

We wonder whether there might also be the idea that, dramatically, older rulers, like Theoden

And Denethor

might be more inclined to listen to such a person (although we notice that the corrupted Denethor is less than willing).

And, that younger men like Aragorn

and Faramir

would see them as mentors.

And, as the Istari have been sent by the Valar, the last act on Gandalf’s part, as depicted in this Hildebrandt twins’ painting, has special significance, suggesting that, Aragorn has been given the throne with divine approval and, with his crowning, Sauron has been completely defeated and balance has been restored, even if only temporarily, to Middle-earth.

When this has been accomplished, Gandalf is then allowed to “retire”, as we seem to expect old men to do in our world (and as Tolkien himself did, in 1959), going to the Grey Havens and a final journey back to the West.

We hear nothing more of Radagast and the two so-called “Blue Wizards”, but, Saruman also leaves Middle-earth—though not in Gandalf’s gentle way. And perhaps his end, shabby and disgraced, also shows a kind of divine approval: those given power must not abuse it, for the consequences not only to the world around them, but to them, can be fatal.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD

PS

Our title is an adaptation of the first line of W.B. Yeats’ gorgeous poem, Sailing to Byzantium (first published in 1928). Although it has nothing to do with Middle-earth, it does depict a strange, magical place.