Welcome, dear readers, to our first posting for 2017—and a Happy New Year.

In our last, we discussed water-crossings in The Lord of the Rings, but said that our next would be on a more specialized subject, something we thought to call “Battle Bridges”.

This was inspired by this quotation (it’s Boromir speaking, at the Council of Elrond):

“I was in the company that held the bridge, until it was cast down behind us. For only four were saved by swimming: my brother and myself and two others.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book 2, Chapter 2, “The Council of Elrond”)

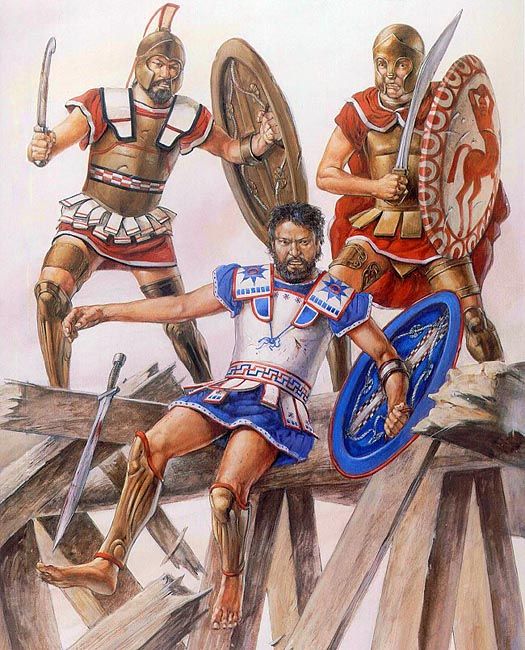

Broken bridges and swimming soldiers made us think of a story told by a number of early historians, including Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Livy, Pliny the Elder, and Tacitus, in which three Roman officers stand as a rearguard at the first bridge over the river Tiber, the Pons Sublicius, and, when two are wounded, the third, Horatius, sends them off, telling them to have the bridge destroyed so that the enemy can’t pursue the defeated Roman army into Rome. When the bridge is gone, Horatius, in his armor and with his arms, leaps into the river and swims to the Roman shore to great acclaim.

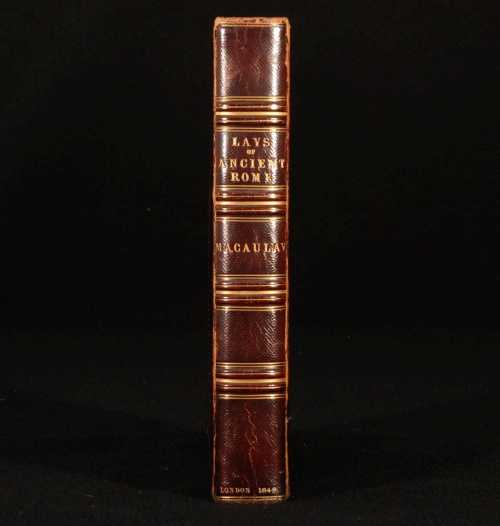

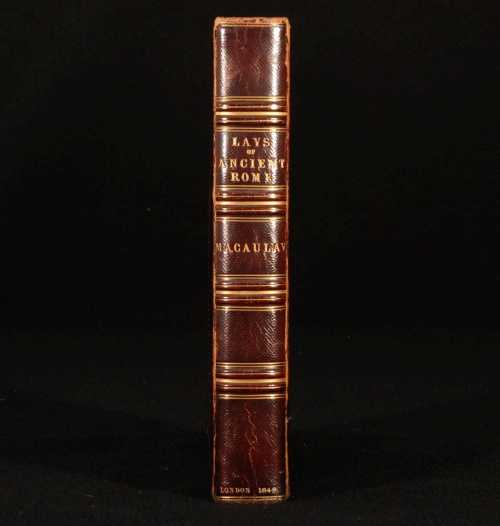

In the nineteenth century, this story was turned into a poem (a very long ballad) by the historian Thomas Babington, Lord Macaulay (1800-1859),

entitled “Horatius at the Bridge” (from his 1842 collection, The Lays of Ancient Rome).

Once upon a time, it was a standard assignment for schoolboys to memorize its approximately 600 lines and we wonder if this might once have been Tolkien’s task, which is why we have Boromir’s remark.

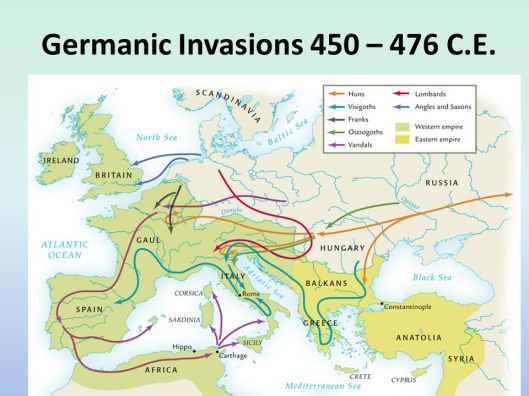

Once we embarked upon the subject of fights at bridges, we found, beginning with the late classical world, that there were lots more out there (our short mental list roared through time to take us as far as the seizing of Pegasus Bridge in the Normandy invasion and the subsequent bridges at Arnhem and Remagen). There was a difficulty, however: we began with an heroic action—one man or a handful against masses. What mostly came to mind was not Horatian one-man stands. Instead, they were only depicted as parts of larger military maneuvers to gain or block a crossing and individuals disappeared. Take, for example the famous battle at the Milvian Bridge, in 312AD, which led not only towards a reconstituted Roman world based upon the east, but also towards the eventual Christianization of the Roman world.

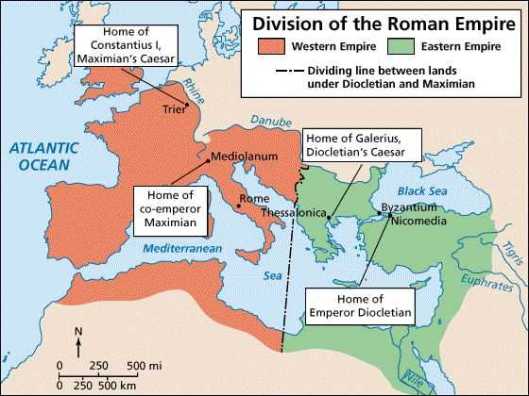

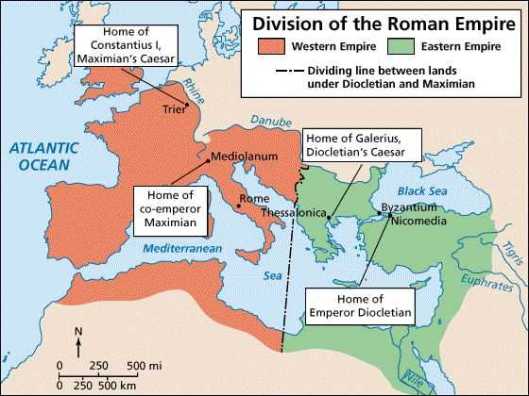

In the civil wars which wracked the late Roman empire, after its division post-284AD by Diocletian,

Constantine, the western Augustus (senior emperor)

defeated his rival, Maxentius (who was also his brother-in-law),

at a bridge outside Rome to become, in time, the sole emperor. Maxentius, who had control of Rome, had planned to block Constantine on the far side of the Tiber, keeping a pontoon bridge available for a retreat, if necessary, since it appears that the actual stone bridge was in the process of being dismantled.

(The Romans were extremely able at producing pontoon bridges—here’s a good illustration from the column of Marcus Aurelius—completed 193AD–)

When that retreat did become necessary, Maxentius was drowned in its midst, the bridge collapsed, and his troops who remained either died on the field or surrendered to Constantine.

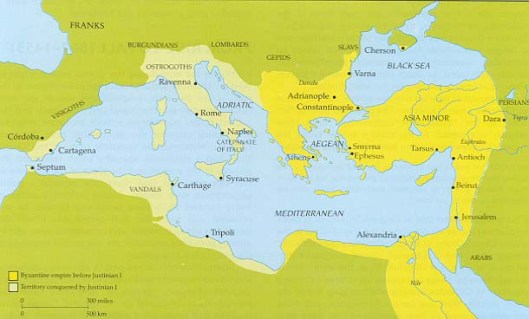

In time, Constantine, who believed that the empire’s main focus should actually be on the east, moved the capital to an old Greek colony, called Byzantium, but which he renamed “New Rome”—although it seems that everyone else called it Constantinople.

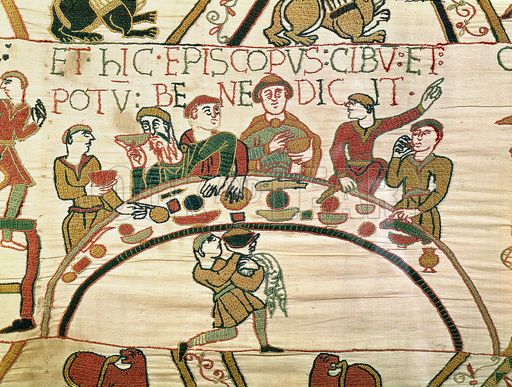

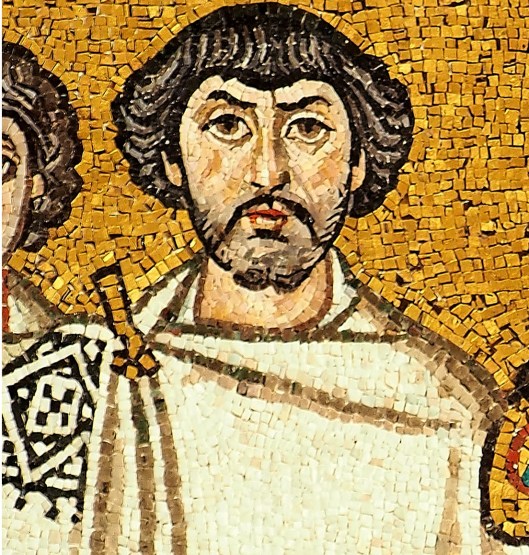

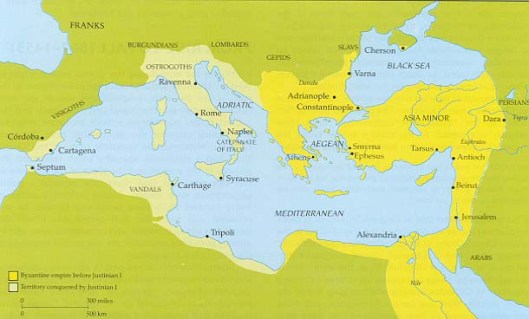

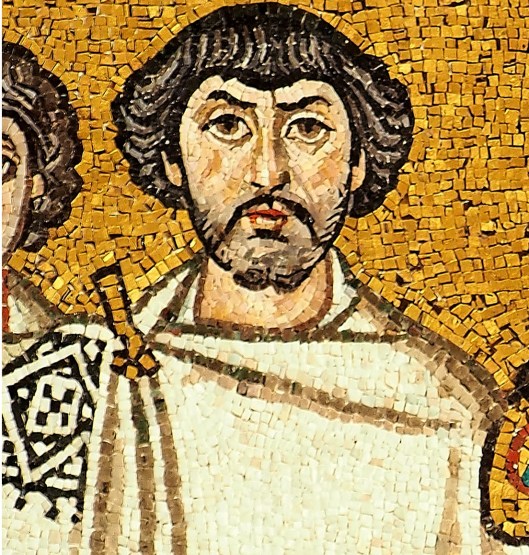

This would be the capital of the later Byzantine Empire, which, under the emperor Justinian,

(He’s the one with the bowl of communion bread—the only labeled figure, Maximianus, was the bishop of Ravenna, where this mosaic stands in the church of San Vitale.)

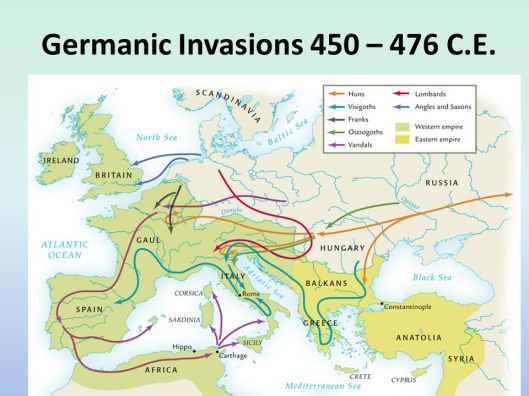

would attempt to reconquer the portions of the old western empire which had fallen into the hands of Germanic invaders.

Under Justinian’s general, Belisarius,

(this may or may not be a portrait—it’s a scholarly guess),

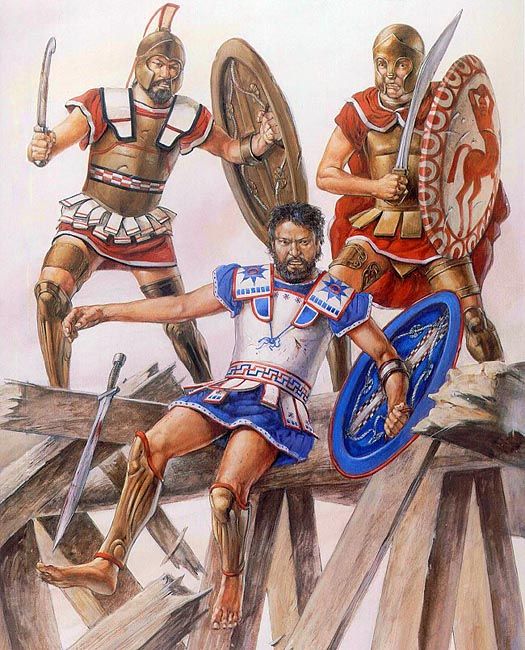

the Byzantines struggled for control of Rome against the Ostrogoths.

This struggle included a fight outside of Rome for control of the Salarian Bridge (537AD),

a fight which Belisarius lost, although, for a short time, Justinian’s world was enlarged, if not to the full size of the old empire, at least to include much of the western Mediterranean—quite an accomplishment for the later world of antiquity.

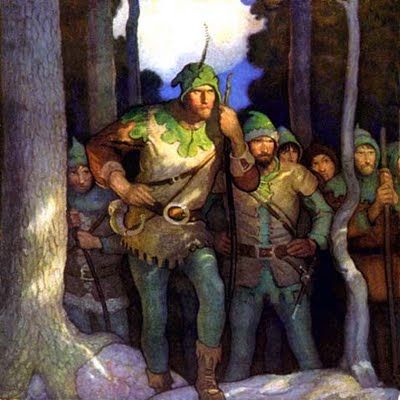

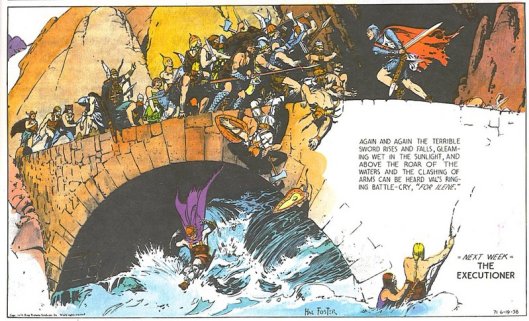

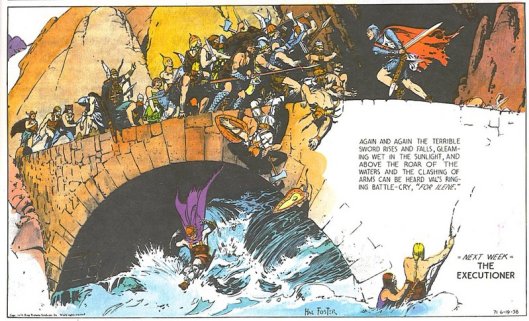

And, speaking of late antiquity, if you regularly read our blog, you know that we have a special affection for the work of Hal Foster, who created the late-antique, early-medieval world of Prince Valiant. The combination of bridge and heroic fighting reminded us of one of our favorite illustrations and so we have to include this scene (published 19 June, 1938), in which Val faces a band of Viking raiders.

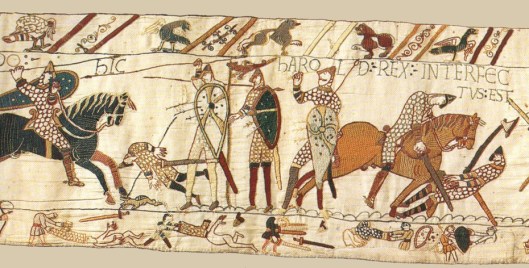

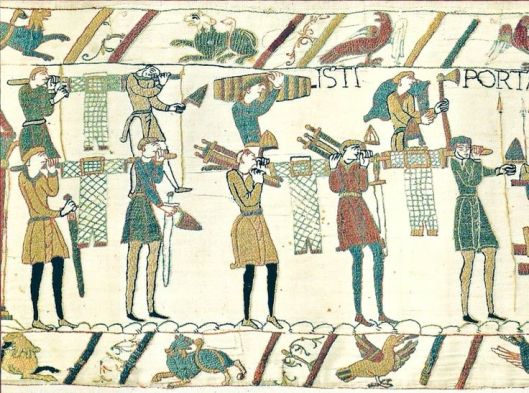

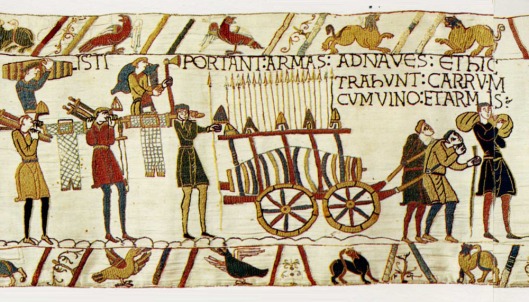

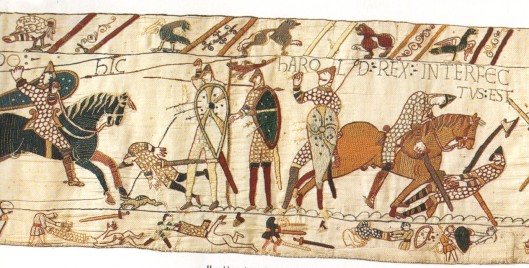

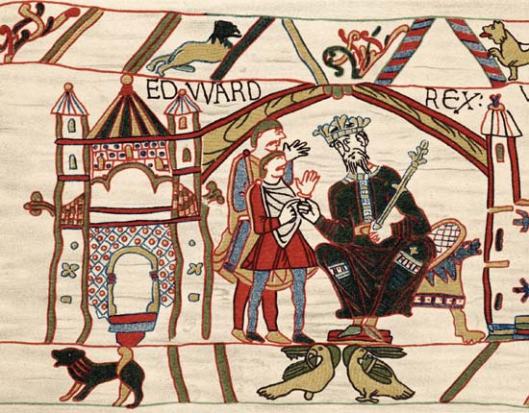

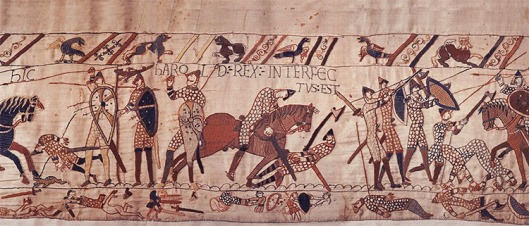

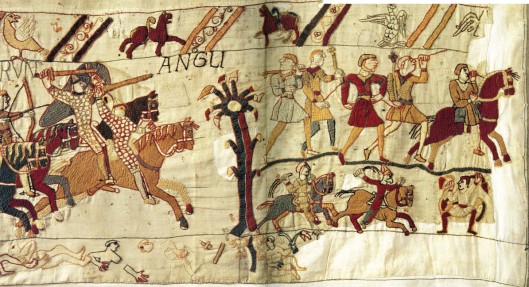

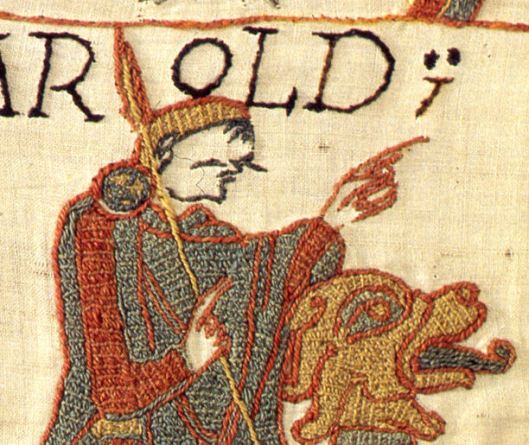

This image, of course, brings us back to Horatius, the single warrior against the mass. As we’ve said, in the intervening centuries there are battles at bridges, but only as one element in larger campaigns and the heroic individual disappears into the ranks. We could think of one, somewhat later, figure, however. He appears, unfortunately nameless, in the other battle of the short reign of Harold Godwinson, at Stamford Bridge, 25 September, 1066. The Anglo-Saxon army raced north from London to oppose a Viking invasion, and defeated the Vikings on the near side of the bridge over the River Derwent, but, to complete their victory, the Anglo-Saxons needed to destroy the surviving force on the far side. in the way stood, in the middle of Stamford Bridge, a single Viking warrior, blocking their advance.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that he killed 40 of the enemy before an Anglo-Saxon floated underneath the bridge and stabbed him from beneath with his spear, but, well, as much as we believe in heroic tales…

His stand, however, brings us back to Boromir and his final battle, in which he faces two waves of orcs before he is finally mortally wounded.

No bridge, but this still follows the theme of the brave man standing alone, with no possible help nearby.

(And, of course, Boromir and his horn are meant to remind any good reader of heroic material—particularly medieval—of Roland at the Pass of Roncevalles…)

We would leave this theme here, back where it began, with Boromir, except we can’t resist (we’re afraid, when it comes to adventure and heroics, that we appear to have little or no willpower at all!) one final image and the idea behind it. There is no end of discussion about Napoleon, which, we’re sure, would please him no end. For us, however, there is a side of him which is endlessly interesting and that is as a Romantic Figure—a view of himself which he worked very hard, at least early in his life, to promote. The late 18th-century very much looked back to the classical world and, we believe, it did so in part because it loved the dramatic gestures it saw as part of that world. We only have to point out paintings like David’s “The Oath of the Horatii”(those Horatii being the direct ancestor of the one in our post), with its operatic ensemble look, to illustrate this. (To us, this looks so much like the set-up for a stirring quartet, right out of Bellini or Meyerbeer.)

So, during Bonaparte’s brilliant 1796-7 campaign in Italy, there was clearly a classical/Romantic moment. When the French were stalled by their Austrian opponents in crossing the River Adige, Napoleon, to encourage his troops, seized a regimental color and raced alone to the bridge, as Gros (who was actually at the battle) depicted him in his 1797 painting.

Vernet, in his 1826 version, continues the heroic theme, but changes the focus a bit—Napoleon now has followers. (And you know, from its dash—and that’s Horace Vernet in general—who, according to Sherlock Holmes, may be a distant relation–that this is a favorite painting of ours.)

In fact, although Bonaparte did seize a color, he never made it to the bridge, either alone or in a crowd. His illustrators, however, influenced, no doubt, by the potential drama—and perhaps by a faint memory of Horatius?—depict a scene which should have happened, in their view of Napoleon as a Romantic Figure. What is most striking, however, is that, unlike Horatius—or Boromir—Bonaparte is not defending a bridge—he is attacking and his heroism comes from that gesture. This certainly fits in with Revolutionary ideology—France had been at war with much of the world since 1792—but it occurs to us that it may also suggest a shift in the approach to heroism. Horatius, given a bridge, is heroic, but passive. Give a bridge to Bonaparte and stand back (at least in iconography)! Is this the image of heroes in the Romantic world which was just coming into being?

But, as ever, we leave this to you, dear readers, to ponder, even as we thank you, as always, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD