Dear readers, welcome, as always.

JRRT was well aware of anachronisms and, in his 1966 revision of The Hobbit, he replaced certain items. Certain ones remained, however, including:

“…In that last hour Beorn himself had appeared—no one knew how or from where. He came alone, and in bear’s shape; and he seemed to have grown almost to giant-size in his wrath.

The roar of his voice was like drums and guns…” (The Hobbit, Chapter 18, “The Return Journey”)

This is the narrator speaking and it has been argued, quite plausibly, to my mind, that he’s someone speaking in the 1930s, telling a tale to his children, and therefore is perfectly justified in using things which are normal in his own time period, as out of place as they might be in Bilbo’s world. (Although Gandalf is known for his fireworks,

meaning that gunpowder is available, and, as we know from explosions at Helm’s Deep and the Causeways Forts, Saruman and Sauron both appear to use some sort of explosive.)

(This is by the brilliant Grant Davis, a Lego wizard—you can read something about him here: https://www.georgefox.edu/journalonline/summer19/feature/building-blocks.html )

Drums, however, are a different matter and, when it comes to Tolkien, I always immediately think of

“…We cannot get out. The end comes, and then drums, drums in the deep.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 5, “The Bridge at Khazad-dum”)

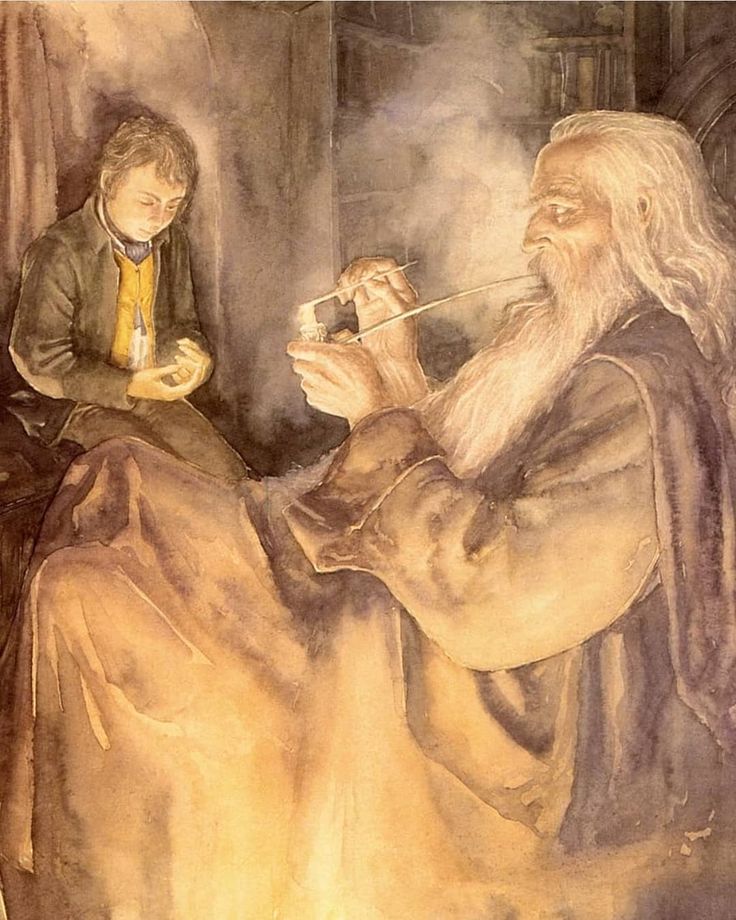

Gandalf has been reading to the Fellowship from a ruined diary of the reoccupation of Moria by the dwarves

as they sit in what was once the Chamber of Records, having no idea that, very soon, they could be duplicating the same doomed words as orcs attack them.

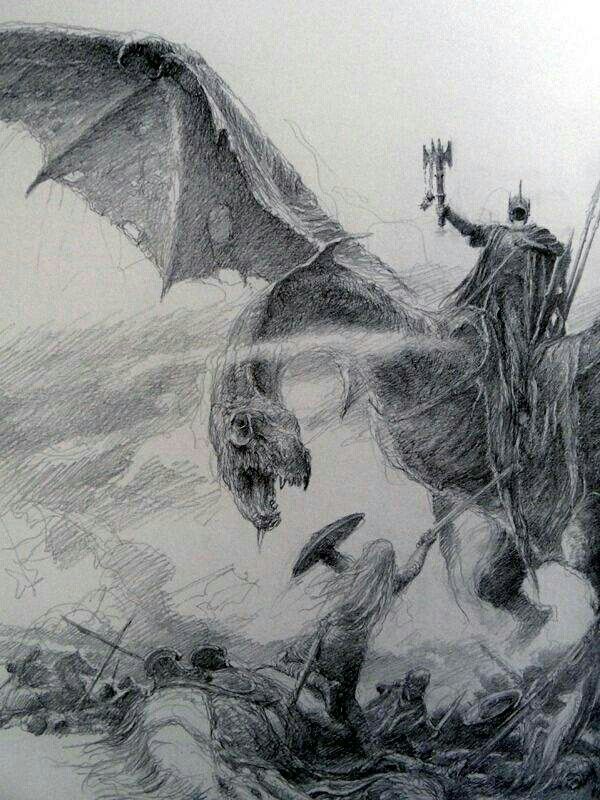

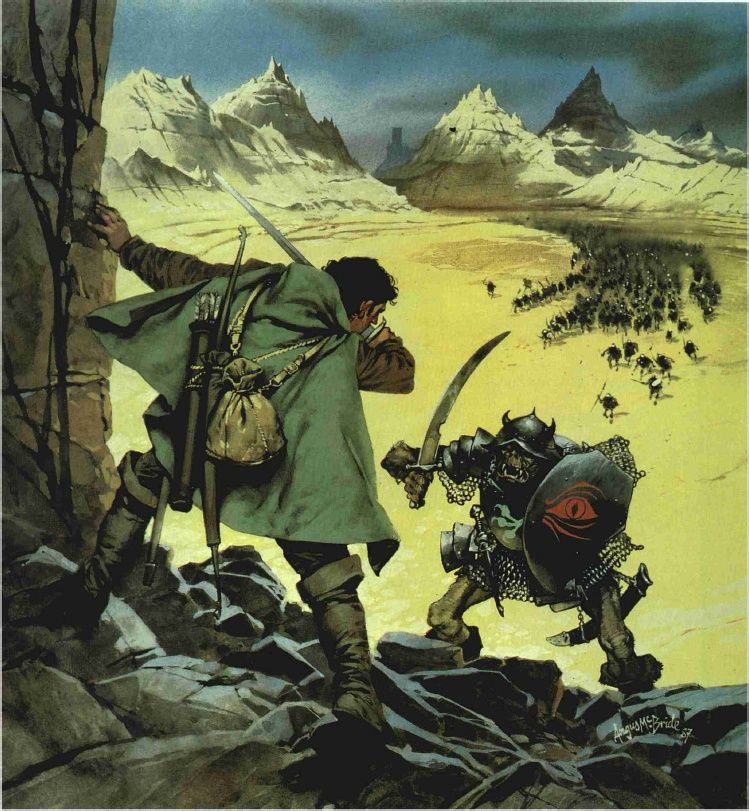

(Angus McBride)

“Gandalf had hardly spoken these words, when there came a great noise: a rolling Boom that seemed to come from depths far below, and to tremble in the stone at their feet. They sprang towards the door in alarm. Doom, doom it rolled again, as if huge hands were turning the very caverns of Moria into a vast drum. Then there came an echoing blast: a great horn was blown in the hall, and answering horns and harsh cries were heard farther off. There was a hurrying sound of many feet.

‘They are coming!’ cried Legolas.

‘We cannot get out,’ said Gimli.

‘Trapped!’ cried Gandalf. ‘Why did I delay? Here we are, caught, just as they were before. But I was not here then. We will see what—‘

Doom, doom came the drum-beat and the walls shook.”

And this booming sound will pursue the company all the way to the Bridge of Khazad-dum itself.

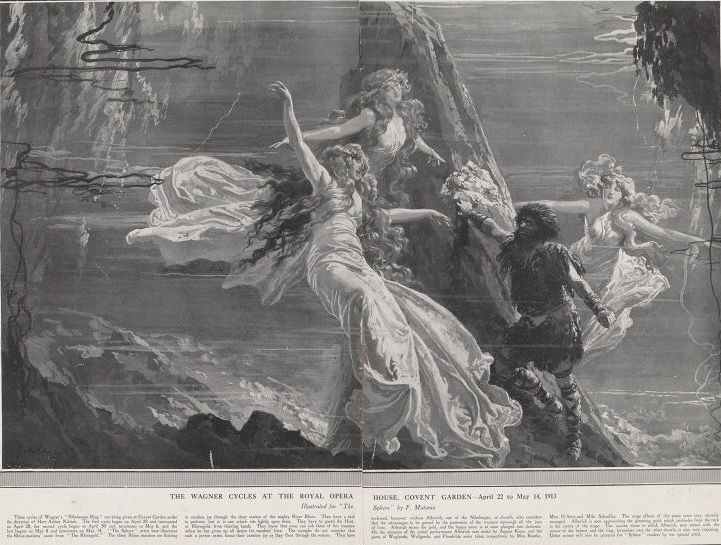

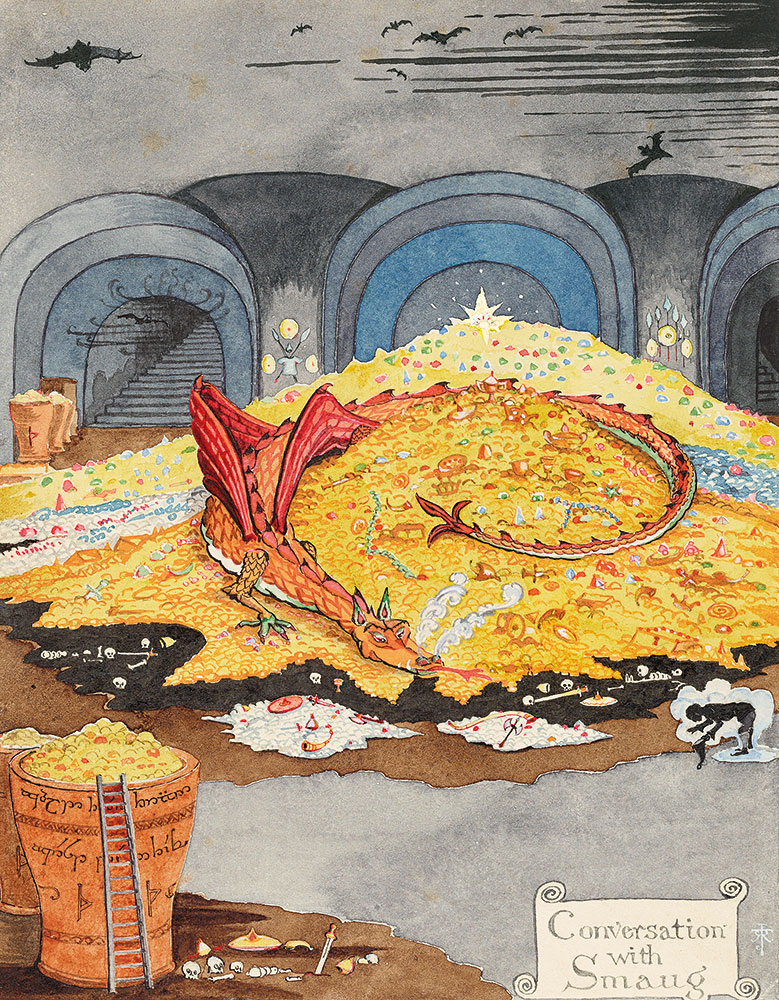

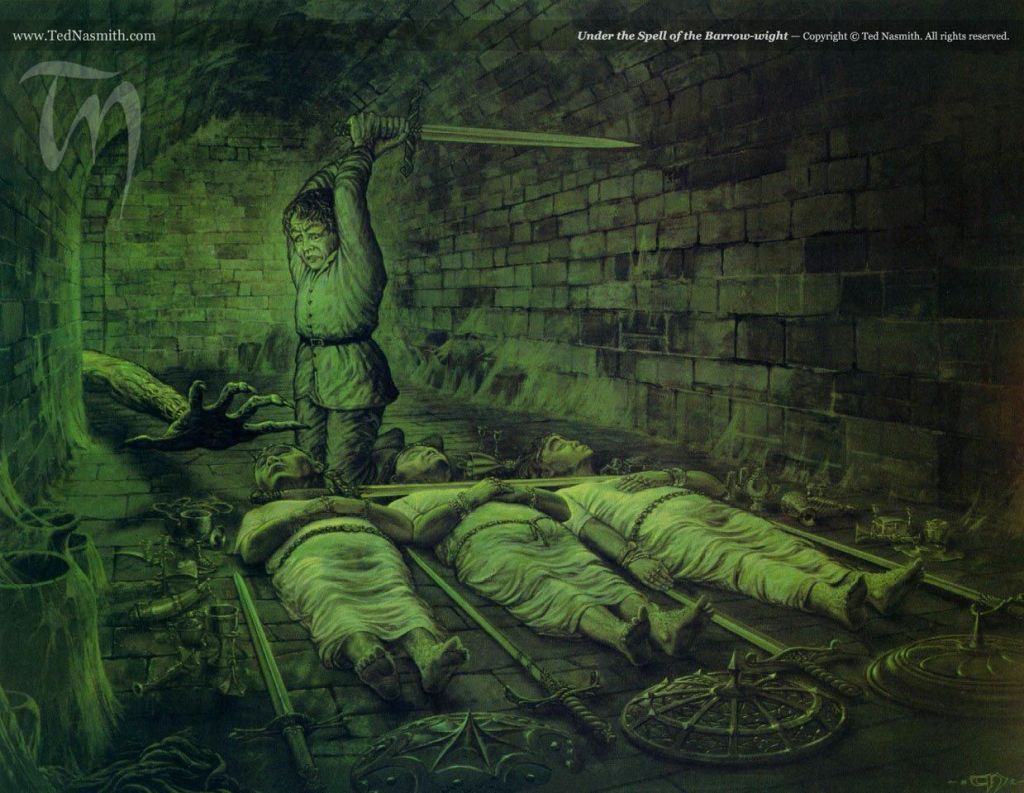

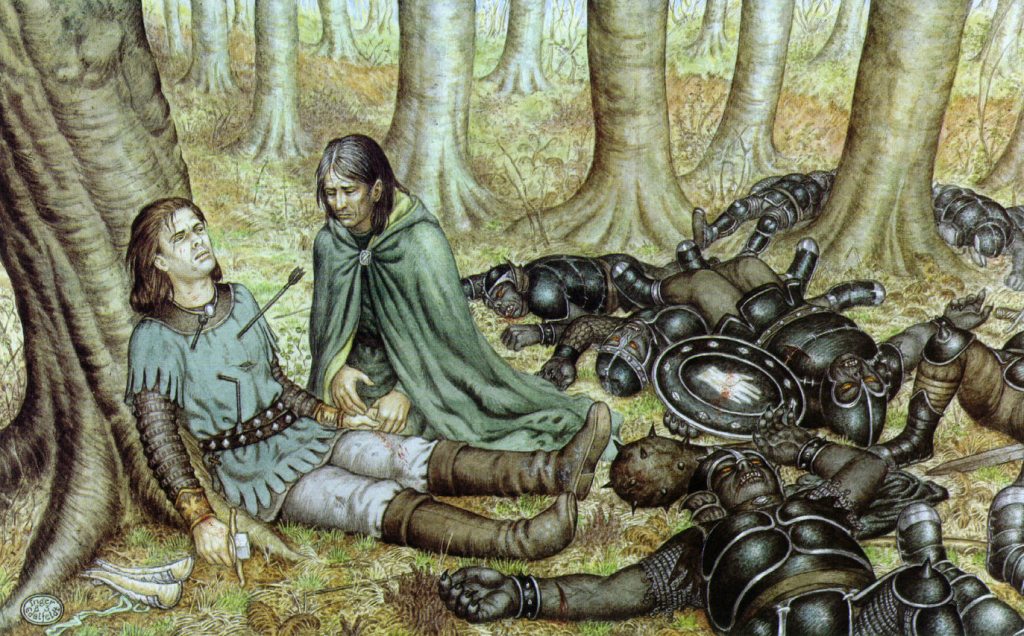

(Alan Lee)

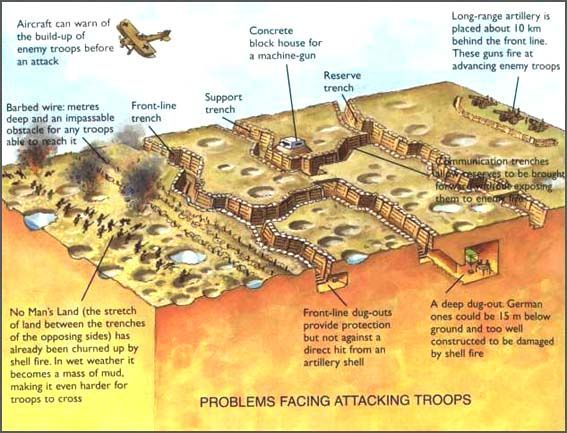

We never see this drum, but I’ve always wondered what it and other drums used by the orcs and other opponents of the Fellowship and their friends might have looked like and, if possible, sounded like.

Certainly whatever the orcs are using here must be rather large to penetrate the stone walls of Moria.

My first choice might be o-daiko, a Japanese drum which can be as big as six feet in diameter

and I’ve seen mention of one which is almost ten feet. It is played with two large, thick wooden sticks, called bachi,

and has been used for everything from folk festivals to war to theatre. By itself, it has a deep boom, but played in groups…

You can read about it here: https://instrumentsoftheworld.com/instrument/131-Odaiko.html and hear and watch three drummers here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C7HL5wYqAbU (And perhaps I should add some sort of warning here: they’re not only loud, but frenzied and, well, the sound can carry you away…)

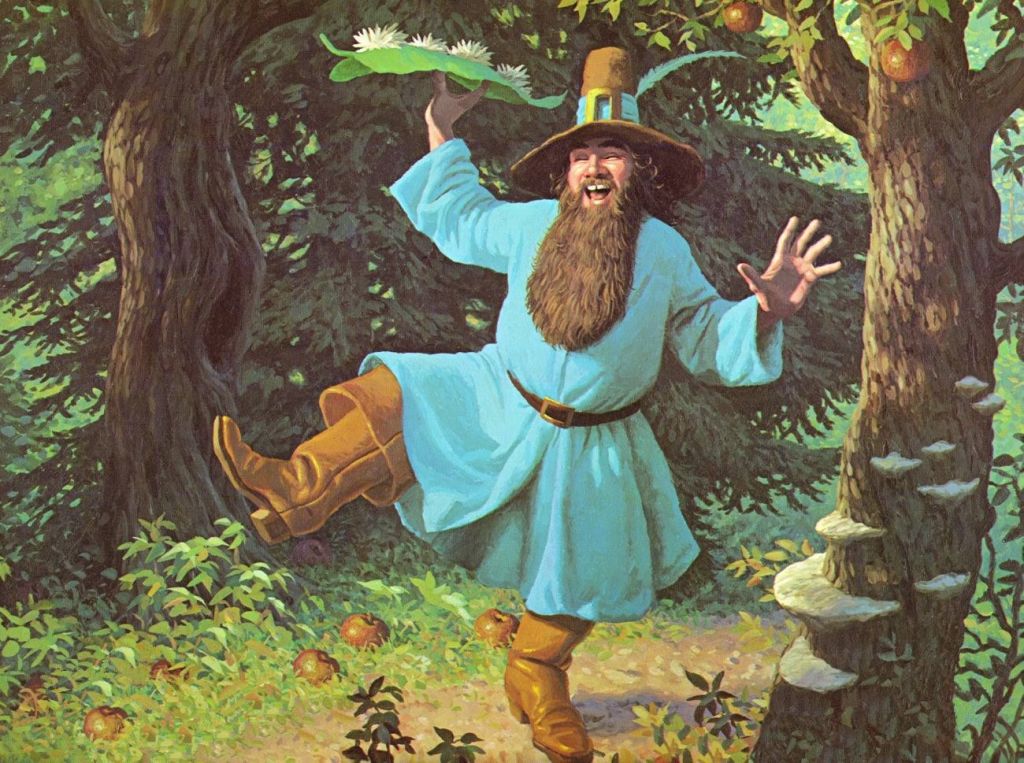

And what about the Haradrim? Here’s how they are depicted in the Jackson films—

(They are wearing, to me, a very odd helmet/mask, making them look a little like mechanical pandas—which is, I admit, a pretty terrifying thought!)

(By the wonderfully creative Patrick Lawrence. You can see more of his work here: https://pwlawrence.com/ )

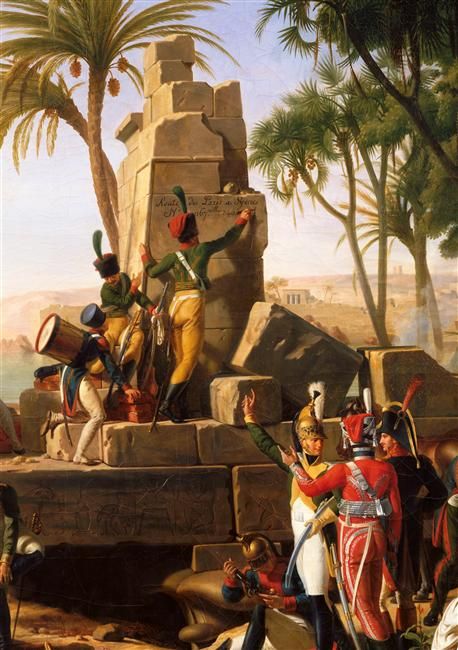

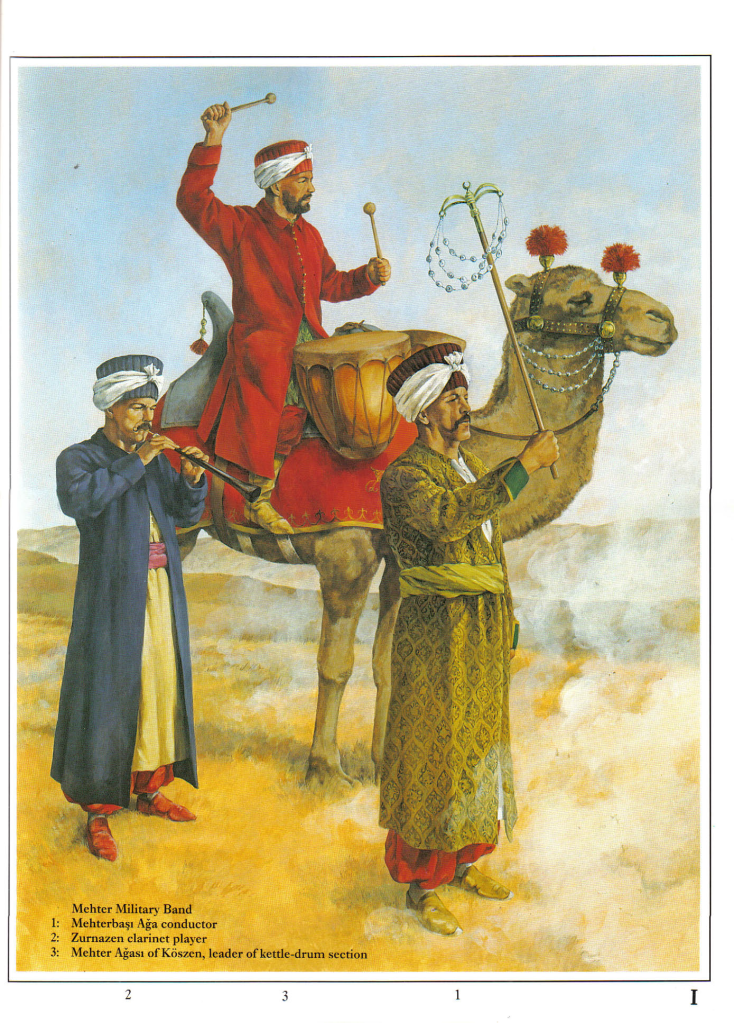

but I’ve always pictured them as more like the Ottoman Turks, the sort who came to dominate southeastern Europe from the 14th century on, captured Constantinople in 1453,

and almost captured Vienna twice—in 1529 and again in 1683.

Their terror weapon—besides their fearsome reputation—was their music, often called mehter in the West.

Drums, cymbals, wind and brass instruments combined to make a very fierce sound—as you can hear here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ktBSoeSmMio and you can read more about them here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ottoman_military_band )

And I’d add to all of this booming racket one more sound from the enemy:

“For Anduin, from the bend at the Harlond, so flowed that from the City men could look down it lengthwise for some leagues, and the far sighted could see any ships that approached. And looking thither they cried in dismay; for black against the glittering stream they beheld a fleet borne up on the wind: dromonds, and ships of great draught with many oars, and with black sails bellying in the breeze.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 6, “The Battle of the Pelennor Fields”)

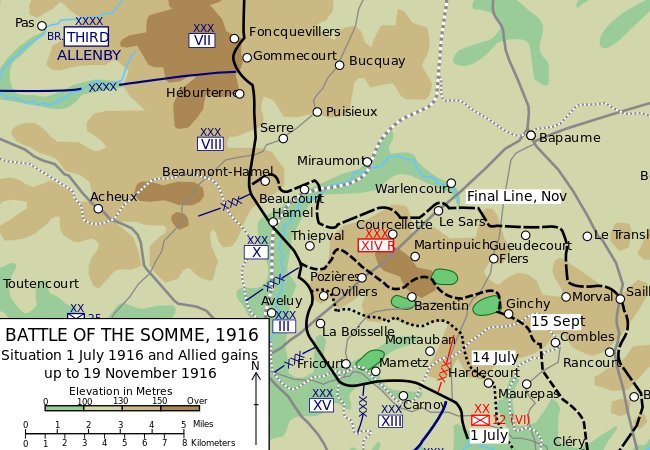

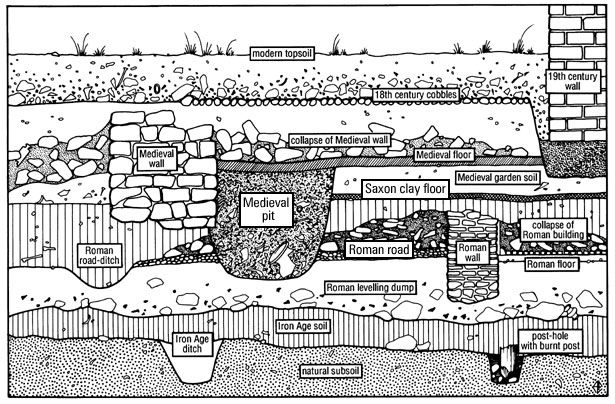

Here’s a dromond (this is a version of the word dromon, “runner”, the name of the standard Byzantine warship)

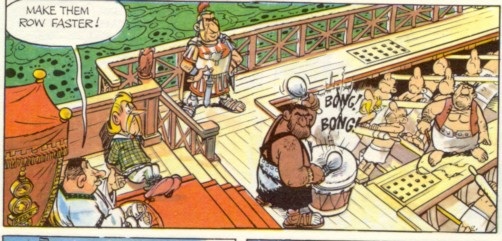

and you’ll notice that it is an oared vessel, as are those which JRRT describes as“ships of great draught”. To coordinate the oars, a basic tempo must be kept and that would mean, traditionally, a drum—and a fairly large one, too, to carry the rhythm across the ship, rather like the cartoons we always see of Roman galleys, like this from the French comic Asterix—

You can see/hear a classic rowing scene here (from the 1959 Ben Hur): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ax7wcShvrus

So, as advertised in the title of this posting, no guns, but certainly lots of drums—perhaps Howard Shore would consider a second edition of his score?

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

If rammed, be sure to have your life jacket handy (and plan to save the Roman admiral, as Ben Hur does),

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

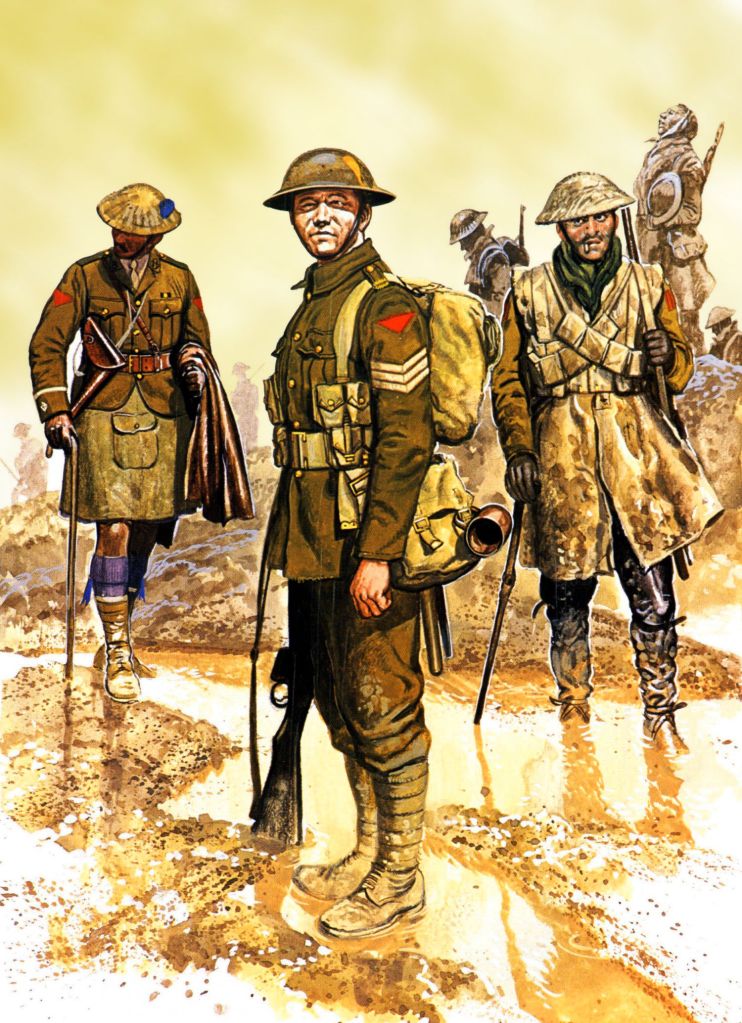

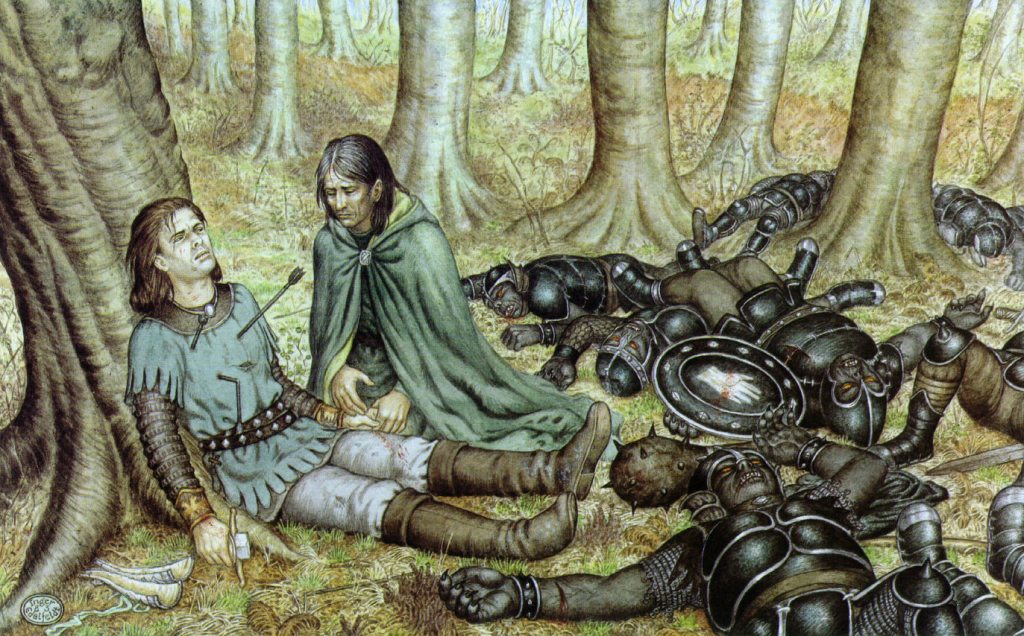

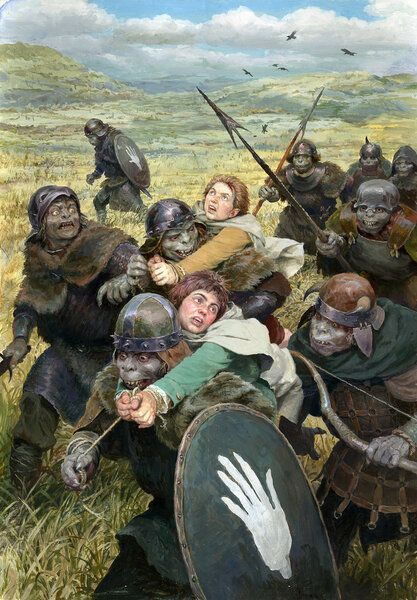

I couldn’t resist adding this image—surely the Haradrim from the far south would have had camels—and kettle drums?

(not sure of the artist–perhaps Richard Hook?)