Tags

allergory, Common Speech, languages of Middle-earth, Monsters and the Critics, Tolkien, Tower of Babel

Dear readers, welcome, as always.

For someone who claimed that he disliked allegory (see, for example, his letter to Milton Waldman, late 1951, Letters, 204), it might seem odd that Tolkien devised one, which we can read near the beginning of “Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics”:

“A man inherited a field in which was an accumulation of old stone, part of an older hall. Of the old stone some had already been used in building the house in which he actually lived, not far from the old house of his fathers. Of the rest he took some and built a tower. But his friends coming perceived at once (without troubling to climb the steps) that these stones had formerly belonged to a more ancient building. So they pushed the tower over, with no little labour, in order to look for hidden carvings and inscriptions, or to discover when the man’s distant forefathers had obtained their building material.” (7-8)

Tolkien goes on to explain his allegory as being about Beowulf and its critics over the years, including more recent ones—

“To reach these we must pass in rapid flight over the heads of many decades of critics.”

It’s the beginning of the next sentence which then interests me: “As we do so a conflicting babel mounts up to us…” (8)

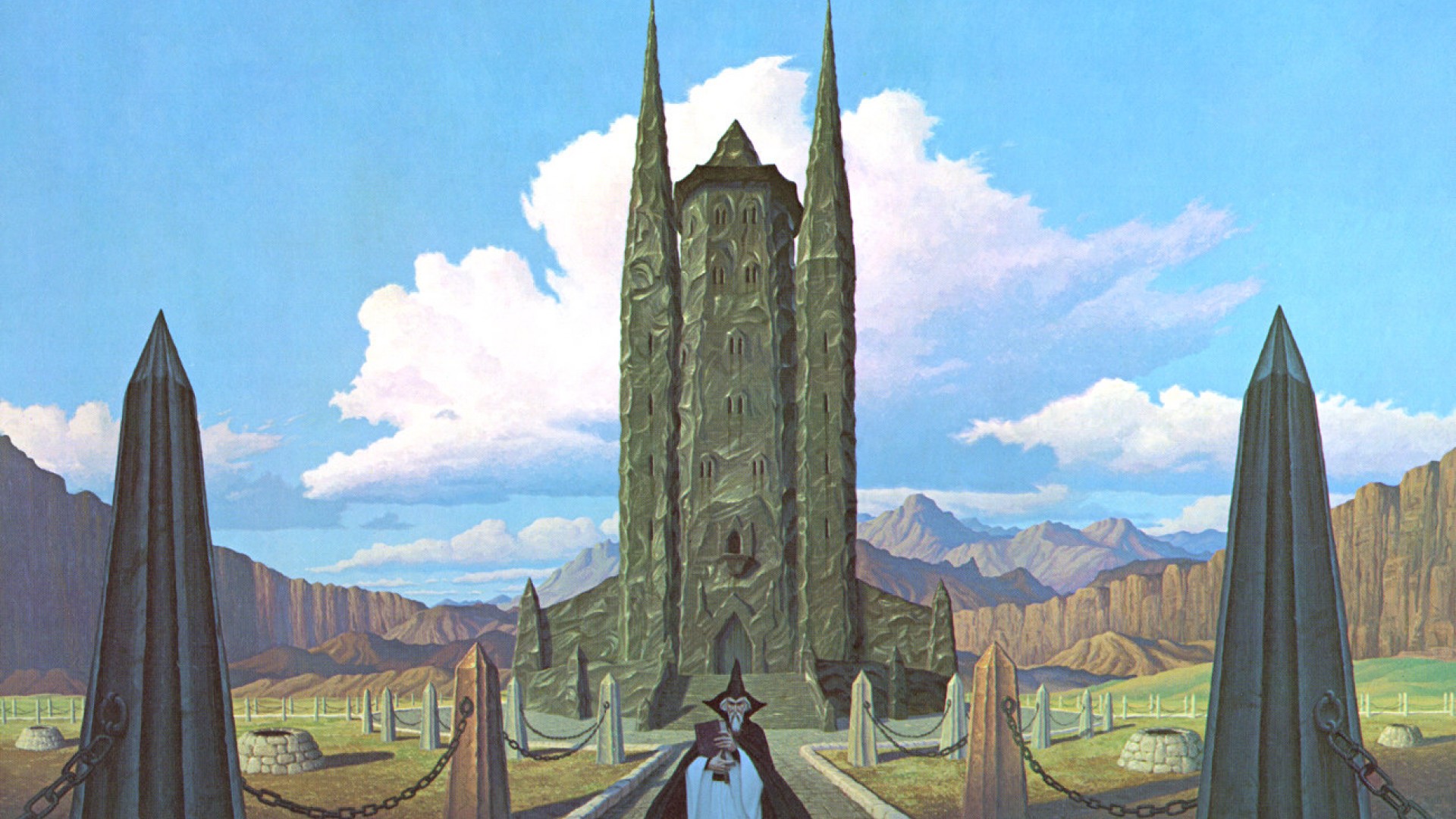

From that word “babel”, we can see where Tolkien probably acquired his central image–

(from the early 15th-century Bedford Hours—for more see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bedford_Hours )

and its basis–

“1 Erat autem terra labii unius, et sermonum eorumdem.2 Cumque proficiscerentur de oriente, invenerunt campum in terra Senaar, et habitaverunt in eo.3 Dixitque alter ad proximum suum: Venite, faciamus lateres, et coquamus eos igni. Habueruntque lateres pro saxis, et bitumen pro cæmento:4 et dixerunt: Venite, faciamus nobis civitatem et turrim, cujus culmen pertingat ad cælum: et celebremus nomen nostrum antequam dividamur in universas terras.5 Descendit autem Dominus ut videret civitatem et turrim, quam ædificabant filii Adam,6 et dixit: Ecce, unus est populus, et unum labium omnibus: cœperuntque hoc facere, nec desistent a cogitationibus suis, donec eas opere compleant.7 Venite igitur, descendamus, et confundamus ibi linguam eorum, ut non audiat unusquisque vocem proximi sui.8 Atque ita divisit eos Dominus ex illo loco in universas terras, et cessaverunt ædificare civitatem.9 Et idcirco vocatum est nomen ejus Babel, quia ibi confusum est labium universæ terræ: et inde dispersit eos Dominus super faciem cunctarum regionum.”

“The earth was of one language, however, and of the same speech. And when they were setting forth from the east, they found a plain in the land of Senaar and they settled in that [place]. And one said to his neighbor, ‘Come, let us make bricks and bake them with fire.’ And they had bricks in place of stones and pitch in place of cement. And they said, ‘Come, let us make a city and tower for ourselves, whose top may reach the sky; and let us glorify our name before we may be split up into all the lands.’ The Lord came down, however, so that he might see the city and the tower which the sons of Adam were building and said: “Look—there is one people and language for all. They have begun to do this nor will they desist from their plans until they may fill them with [their] labor. Come, therefore. Let us go down and confuse their speech there so that each one may not hear [i.e. understand] the tongue of his neighbor.’ And so the Lord split them up from that place into many lands and they stopped building the city. And on account of that the name of this [place] has been called “Babel” since there the speech of the whole land has been confused and thence the Lord scattered them over the surface of all the regions.” (Genesis 11.1-9, my translation—the meaning of “Babel” and its origin have been the subject of scholarly argument—see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tower_of_Babel )

It’s interesting, however, to see that this is a tower of Babel in reverse: instead of it being built, it is being pulled down—although, as in the case of the Biblical tower, events around the tower produce confusion: in the case of Babel, linguistic; in the case of Tolkien’s tower, critical, with so many differing opinions about approaches to Beowulf.

In our world, Tolkien had early been concerned with the fact that the earth was full of languages, Biblically created or not, for which he believed that a common language, a lingua franca, might be a cure, a cure he believed might lie in Esperanto:

“Personally I am a believer in an ‘artificial’ language, at any rate for Europe—a believer, that is, in its desirability, as the one thing antecedently necessary for uniting Europe, before it is swallowed by non-Europe; as well as for many other good reasons—a believer in its possibility because the history of the world seems to exhibit, as far as I know it, both an increase in human control of (or influence upon) the uncontrollable, and a progressive widening of the range of more or less uniform languages. Also I particularly like Esperanto…” (“A Secret Vice”, in Tolkien, The Monsters and the Critics, 198. For more on Esperanto, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Esperanto and https://ia800205.us.archive.org/13/items/esperantotheuniv00ocon/esperantotheuniv00ocon.pdf and for more on Tolkien and the subject, see: Arden R. Smith, “Tolkien and Esperanto”, Journal of the Marion E. Wade Center, Vol.17 (2000), 27-46)

For Europe perhaps one language, then, but, for Middle-earth?

If we only think of those spoken or mentioned in The Lord of the Rings, we find numerous languages—not surprising for someone who more than once had said that he created people so that there would be someone to speak his languages (see, for example, his letter to Houghton Mifflin, 30 June, 1955, Letters, 319—note: this is only a rough list for a much more complicated subject—for more, see, for example, The Lord of the Rings, Appendix F, I, “The Languages and Peoples of the Third Age”). Here is a basic roster:

1. the Elves (Quenya and Sindarin—for more, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elvish_languages_of_Middle-earth )

2. the Dwarves (Khuzdul)—for a very good, linguistically-based essay on this, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khuzdul

3. the Rohirrim (Rohirric—or Rohanese—or simply Rohan—see this essay for more on the various possible names for the language: https://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/Rohanese ) The Hobbits appear to have spoken at some point in their history a related language—see Appendix F “Of Hobbits” for more.

4. the Dunlendings and the Wild Men of Druadan Forest (? descended from very early humans in Middle-earth—in Appendix F, Tolkien describes their language: “Wholly alien was the speech of the Wild Men of Druadan Forest. Alien, too, or remotely akin, was the language of the Dunlendings.”)

5. the Ents (seemingly invented their own language, described in Appendix F as “…unlike all others: slow, sonorous, agglomerated, repetitive, indeed long-winded…”)

6. men (here meaning descendants of the Numeroreans—Westron—complicated—see Appendix F “Of Men” for some of that complication)

7. Orcs (“it is said that they had no language of their own, but took what they could of other tongues and perverted it to their own liking”—to which would be added the “Black Speech”, invented by Sauron as—yes, a lingua orca, or common speech—see Appendix F, “Of Other Races”, “Orcs and the Black Speech”)

8. to which we might add the languages of the Easterlings and the Haradrim

And here we’re back to Babel again.

(Gustave Dore, from his very dramatic illustrations for La Bible)

People in Middle-earth can revert to their own languages—

“…Following the winding way up the green shoulders of the hills, they came at last to the wide wind-swept walls and the gates of Edoras.

There sat many men in bright mail, who sprang at once to their feet and barred the way with spears. ‘Stay, strangers here unknown!’ they cried in the tongue of the Riddermark, demanding the names and errand of the strangers.”

“ ‘Well do I understand your speech…yet few strangers do so. Why then do you not speak in the Common Tongue, as is the custom in the West, if you wish to be answered?’ “ (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 6, “The King of the Golden Hall”)

Here Gandalf reveals, that, just as there was Tolkien’s Esperanto in our world, in Middle-earth there was clearly an equivalent: “the Common Tongue”. Descended from the language of the Numenorean invaders of Middle-earth (letter to Naomi Mitchison, 25 April, 1954, Letters, 264), this was just what its name says: it was the common speech of a majority of the people in western Middle-earth—along with the exceptions listed above. To JRRT, it was also the equivalent of the English into which the text had been “translated”. In that same letter to Naomi Mitchison, Tolkien wrote:

“If it will interest you, I will send you a copy (rather rough) of the matter dealing with Languages (and Writing), Peoples and Translation.

The latter has given me much thought. It seems seldom regarded by other creators of imaginary worlds, however gifted as narrators (such as Eddison). But then I am a philologist, and much though I should like to be more precise on other cultural aspects and features, that is not within my competence. Anyway ‘language’ is the most important, for the story has to be told, and the dialogue conducted in a language; but English cannot have been the language of any people at that time. What I have, in fact, done, is to equate the Westron or wide-spread Common Speech of the Third Age with English; and translate everything, including names such as The Shire, that was in Westron into English terms…” (263-264)

In other words, what Tolkien has done is exactly the opposite of what the Lord was said to have done. The account in Genesis tells us that, by “confundens ibi linguam eorum”—“confusing there their language”, the Lord intentionally had caused chaos, breaking up the single people into many groups, each speaking its own language and therefore unable to collaborate in continuing their daring construction. JRRT, by writing—he would say “translating”—his work almost entirely in English (Tolkien had added in the letter to Mitchison “Languages quite alien to the C[ommon] S[peech] have been left alone), has produced a work in which he has brought together the speakers of a number of different languages, combining them into one, in order to produce what—pardon the pun—is a towering achievement.

(This image has produced a fair amount of confusion, it seems, on the internet—in some sources it’s labeled as by Rudolf von Ems, but sometimes another image of the building of the tower is substituted. For the moment, I’ll go with Rudy c.1370—but check out this site for more Babel-building: https://www.babelstone.co.uk/Blog/2007/01/72-views-of-tower-of-babel.html labeled as 72 views of the tower )

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

Consider how dull the world would be with only one language, instead of the more than 7000 currently spoken (see: https://www.worldatlas.com/society/how-many-languages-are-there-in-the-world.html ),

And remember, in any language you like—including Entish—that there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

For more on the languages of Tolkien, there are a number of useful sites such as: https://ardalambion.net/ .