Tags

17th Century fashion, AB Durand, American Revolution, Arthur Rackham, Battle of Kolin, Bram Stoker, Captain Hook, Charles II, Christopher Lee, Darling Family, Darlings, Disney, Dracula, Fenian Cycle, Frederick the Great, Gerald du Maurier, Half Moon ship, Hudson River, J.M. Barrie, N.C. Wyeth, Neverland, Nina Boucicault, Oscar Wilde, Peter and Wendy, Peter Pan, Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, Rip Van Winkle, Saruman, Tepes, The Little White Bird, The Lord of the Rings, The Picture of Dorian Gray, The Wanderings of Oisin, Tinkerbell, Tir na nOg, Tolkien, vampire, Vlad, Washington Irving, WB Yeats

Welcome, as ever, dear readers.

In our last, we spent some time thinking about immortality and Middle-earth. Our main focus was upon the puzzle of Saruman’s seeming dissolution after his murder by Grima.

As one of the Maiar, it would seem that Saruman was, at least potentially, immortal, but his melancholy disappearance would suggest otherwise—perhaps because of his gradual betrayal of the trust the Valar had put in him to be an opponent of Sauron?

We had begun, however, with Bram Stoker’s (1847-1912)

1897 vampire classic, Dracula, and this has made us consider what appears to have been a popular theme in the late-Victorian-to-Edwardian literature we imagine JRRT read, growing up: immortality (or at least lengthened life-span) through, for want of a better word, magic, and several instances immediately spring to mind.

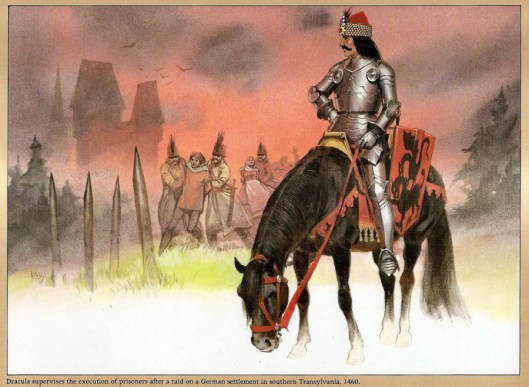

As for Dracula, we know that he was based upon a real late-15th-century eastern European border lord, Vlad, nicknamed “Tepes” (said TSE-pesh), “impaler”, who lived from about 1428 to 1477, when he was murdered.

Stoker’s character has somehow avoided that death and has lived on for a further 500 years—how? By being “un-dead”, a condition whose origin is never really explained, but in which a dead person continues to exist—and even flourish—if able to feed upon the blood of living people. As this is not scientifically possible—dead is dead and actual vampire bats, after all, are alive, even if they drink blood.

All that we can say, then, is that, for all of one of the protagonists’, Dr. van Helsing’s, talk of science, we have no idea what gives Dracula his extended life–though here’s Christopher Lee, as Dracula,

from the 1958 film, Dracula (in the US, Horror of Dracula), with the basis of his continued existence fresh on his lips.

Considering our last post, by the way, it’s an odd coincidence that, in 1958, Lee could play Dracula and in 2001-2003, he would play Saruman.

A few years before Stoker’s novel, in 1889, the young WB Yeats (1865-1939)

had published The Wanderings of Oisin (AW-shin).

This is the story in verse based upon material from the “Fenian Cycle”, the third series of tales about early Ireland preserved by medieval monks. Yeats’ poem deals with an ancient Irish hero who traveled to the Otherworld, spent years there without knowing that it’s a place where time works differently, and returned, only to find that he’d been gone for 300 years and, once he’d actually touched Irish soil, he immediately changed from a vigorous young man to someone 3 centuries old. The place to which Oisin traveled, called Tir na nOg, “the Land of Youth”, is, unfortunately, not found on any ancient map, so, like Dracula’s vampirism, it is simply accepted.

This time-warp also makes us think of the 1819 story of Rip Van Winkle, by Washington Irving (1783-1859).

Rip Van Winkle goes off to hunt in the mountains, the Catskills, to the west of the Hudson River before the American Revolution.

(Here’s an 1864 painting of those mountains by AB Durand (1796-1886), who belonged to the first great group of American landscape painters, called the “Hudson River School”.)

While out hunting, Rip bumps into a group of troll-like creatures, who turn out to be the enchanted members of Henry Hudson’s crew

from his ship, the Half Moon—this is an image of the 1989 recreation of the ship—

with which he explored the Hudson River in 1609.

(We see here Edward Moran’s 1892 painting of Hudson’s ship entering New York harbor.)

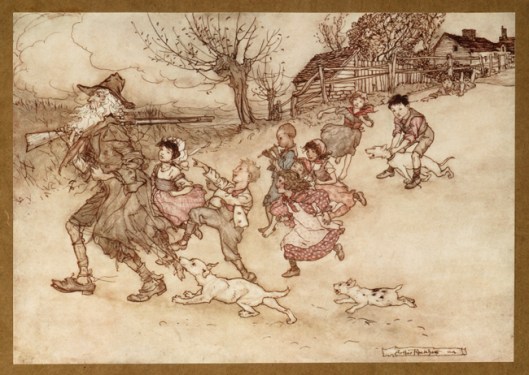

Rip drinks and bowls with them,

then falls asleep, only to awaken over twenty years later to find himself old and now a citizen of the new United States.

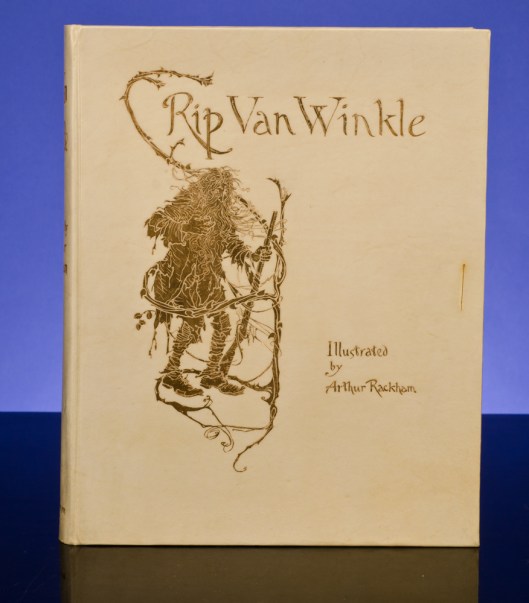

(If you follow us regularly—and we hope you do!—then you know of our great affection for late-19th-early-20th-century illustrators and, when it comes to this story, we’re very lucky in that Arthur Rackham illustrated it in 1905

and NC Wyeth in 1921.)

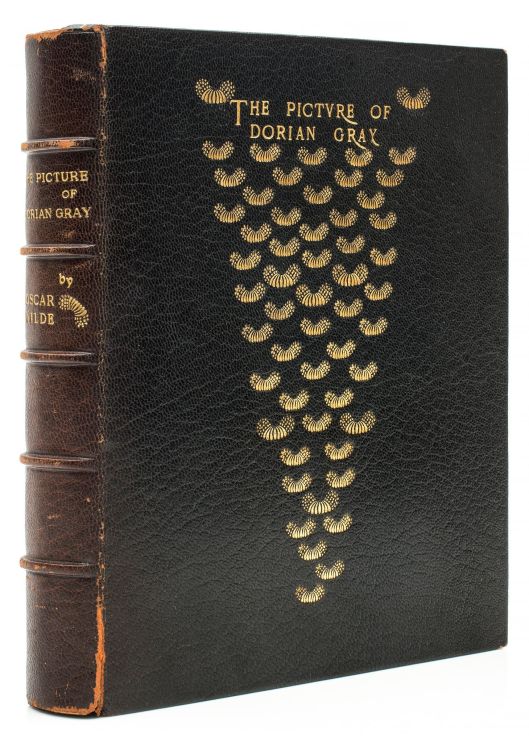

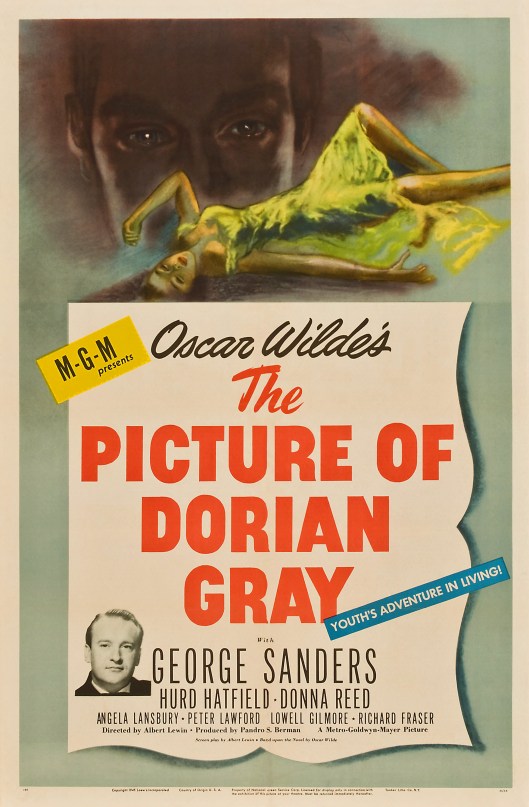

Another late-Victorian story with the theme of the supernatural and long life is Oscar Wilde’s (1854-1900)

The Picture of Dorian Gray, first published in book form in 1891.

The picture here is a sinister one: all of that which would age the protagonist, Dorian—who has an increasingly dark, secret life—is transferred to the image on canvas, so that the sitter for the portrait never seems to age. We can see what that would look like from this image—as well as the tinted version, which is even worse,

from the 1945 film.

How the picture acts as a sponge for all of the worst of Dorian is, like vampirism, never explained—Dorian promises his life if he will never age, but we never see, for example, a satanic figure, standing to one side, nod in agreement.

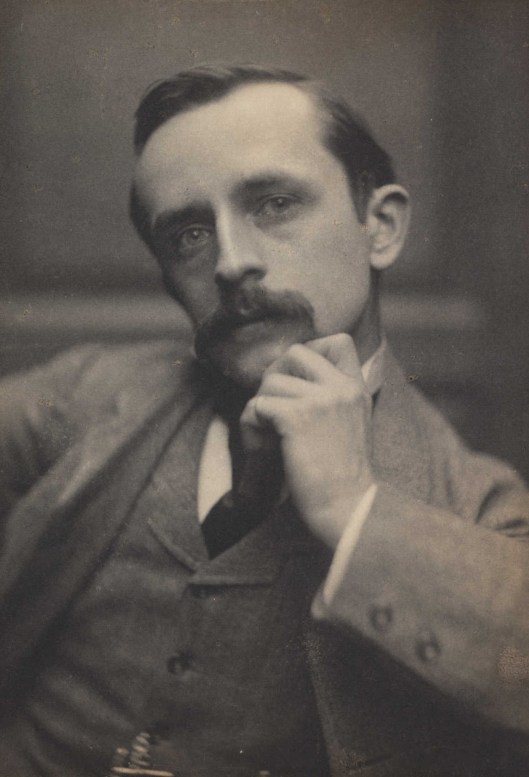

We want to end, however, with a happier story—well, sort of. In 1902, the Scots novelist and dramatist, JM Barrie (1860-1937),

published a novel, The Little White Bird.

In it appeared for the first a seemingly-deathless character, Peter Pan.

Unlike Oisin, who has gone to a magical place, or Dorian Gray, who has his enchanted portrait, Peter just seems to be suspended in time—originally at the age of 7—days—old.

When Barrie returned to the character, in 1904, however, he made Peter grow up–slightly. His age isn’t exactly clear, but we know from the 1911 novelized version, Peter and Wendy,

that he still has his first set of teeth. [Footnote: not a very exact clue—children can begin shedding baby teeth beginning at 6 and continue till 12.] This is the Peter of Barrie’s famous play, Peter Pan,

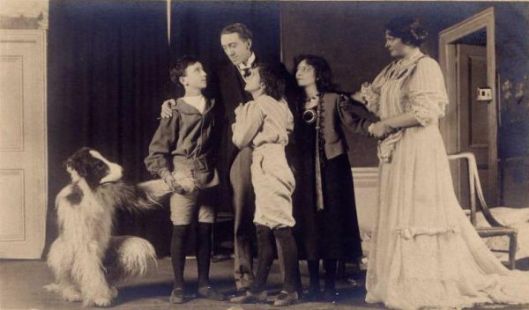

about a boy who lives on an island in Neverland

and, on a visit to London, loses his shadow while eavesdropping on the three Darling children, whose oldest sibling, Wendy, tells stories about him, which she had learned from her mother.

Peter is able to fly and, with the help of a fairy, Tinkerbell, he takes the Darling children back to Neverland with him, where they have all sorts of adventures.

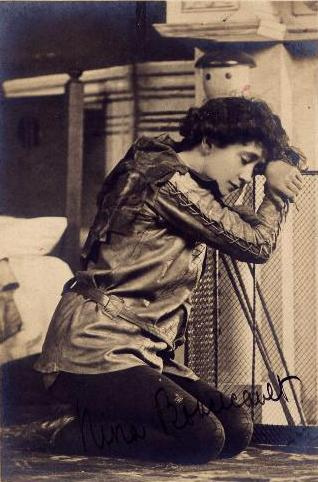

The original Peter—like so many Peters over a century to come—was a woman, Nina Boucicault.

We are lucky to have her costume, which differs a good deal from the Peter Pan everyone knows now from the 1954 Disney film.

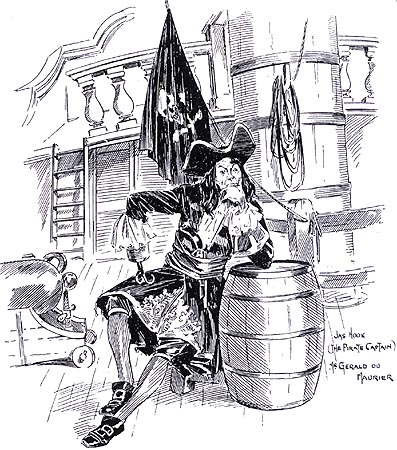

The villain of the piece, Captain Hook, however, has maintained his general outline from 1904.

This is Gerald du Maurier, the original Captain.

Although Barrie himself suggested that Hook should look like someone from the time of Charles II (1660-1685),

to us, he appears to be modeled on the fashions of the late 17th century—note the long coat with the big cuffs, not to mention the big wig.

And here is Disney’s 1954 Hook.

(A footnote: in 1904, Barrie had planned to have different actors play Mr. Darling, the children’s father, and Captain Hook, but du Maurier persuaded him to allow du Maurier to play both roles, which is still the tradition.)

The subtitle of Peter Pan is Or, the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, and here we see, for the first time on our little tour, an explanation for the immortality in which the mortal is an active agent: unlike Dracula or Oisin or Dorian Gray, Peter defies time simply by refusing to acknowledge its effects. He won’t age because he doesn’t want to.

We said that we wanted to end on a “sort of” happy story and Peter’s stubborn immortality might fit that, but Barrie later added a kind of epilogue, a one-act play first performed in 1908. In it, Wendy Darling, the oldest of the Darling children, has now grown up and gotten married, and had a daughter, Jane. One night, while Wendy is putting Jane to bed in the same nursery from which the earlier adventures began, Peter appears.

At first, he simply refuses to believe that Wendy has grown up, and wants her to return to Neverland with him, although she has lost the ability to fly. When she tries gently to explain that she can’t go with him because she has now become an adult, he collapses in tears and she runs from the room, leaving Jane asleep in her bed. Jane wakes up and soon Peter invites her to fly to Neverland with him. When Wendy reappears, she is quickly convinced and off the two go, leaving Wendy behind, but with the hope that Jane will have a daughter and she, in turn, will be taken to Neverland in an endless succession of daughters—perhaps immortality of a different sort? (Here’s a LINK to the play, if you would like to read it for yourself.)

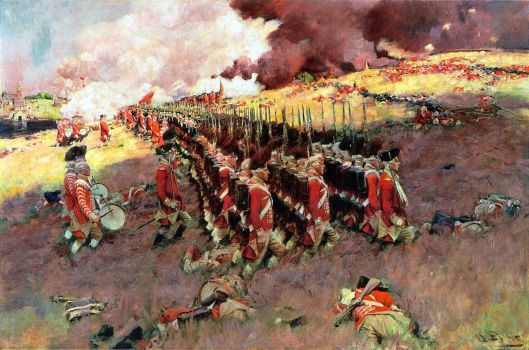

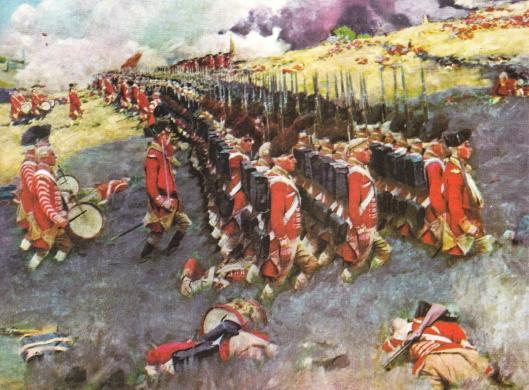

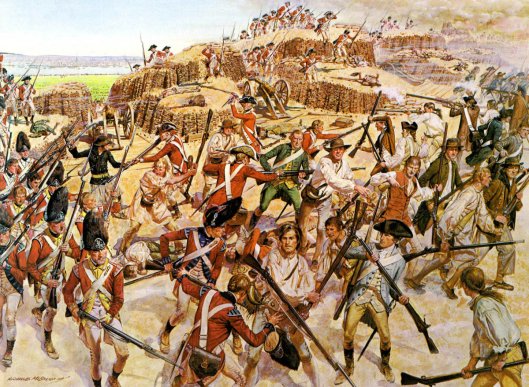

This has been a long posting, but we can’t resist a brief ps. In 1757, Frederick the Great, the king of Prussia (1712-1786), was losing the battle of Kolin. Desperate to win, he tried to rally his men for a counterattack, shouting, “You rascals! Do you want to live forever?”

Virtually no one followed him, so we guess that most did.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

MTCIDC

CD

PS

And another ps—in 1924, the first film version of Peter Pan appeared.

It was much praised at the time and here’s a LINK so that you can see it for yourself.