As always, dear readers, welcome.

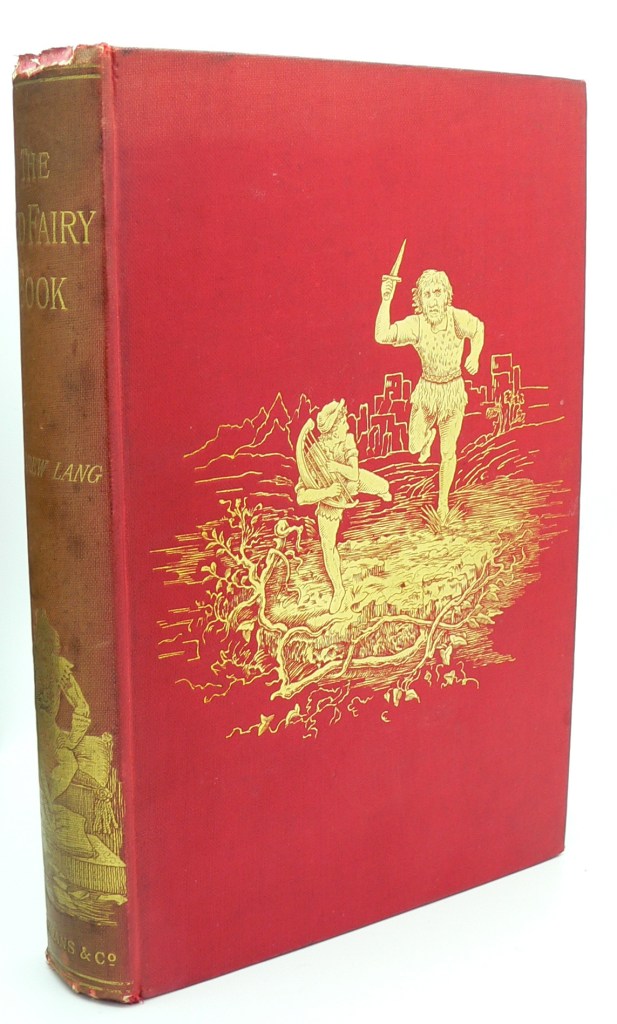

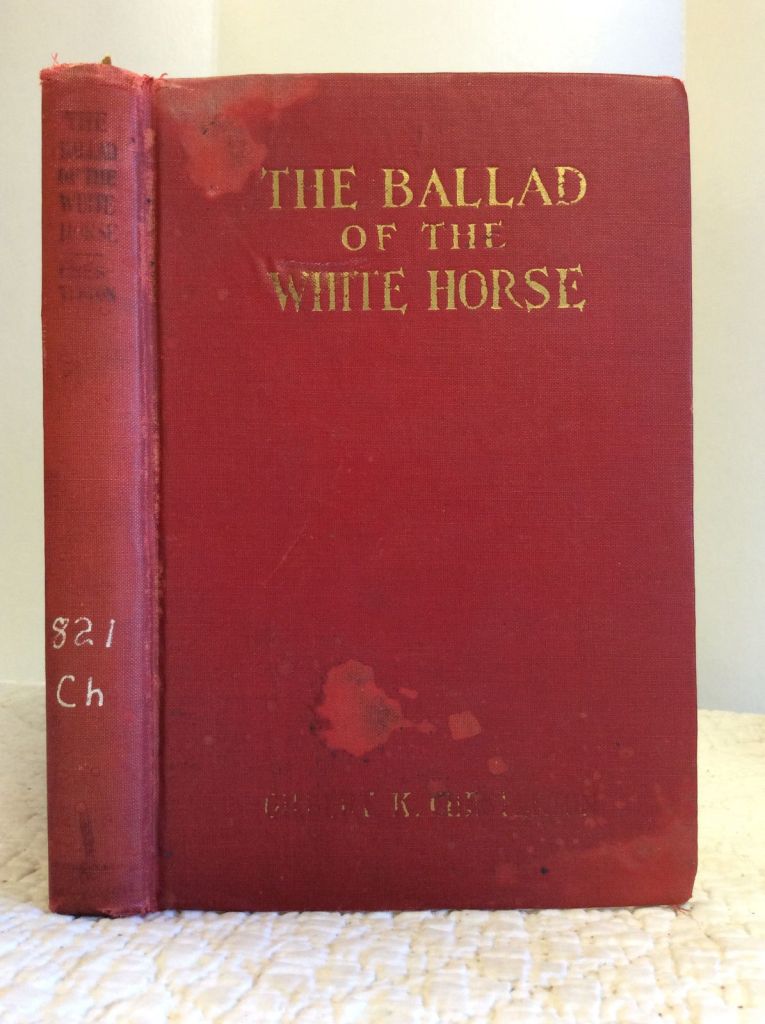

I admit that the title of this posting, upon further reading, may seem a little deceptive. It’s the title of a (perhaps) early 18th-century English song, sometimes called “General Wolfe’s Song” because, somehow, a story appeared that General James Wolfe (1727-1759)

(by George Townshend, 1724-1807, one of Wolfe’s senior officers, who disliked him, but did this little watercolor which, to me, looks much more like the real man than the formal portraits we normally see)

sang it before his death (and victory) at Quebec, in 1759. (This appears to have had no basis in fact, but has been repeated more than once, in various books about English popular song.)

(by Edward Penny, 1763?—this, one of several versions of the picture by the painter, is in the Fort Ligonier museum in Ligonier, Pennsylvania)

The tune, at least, appears to be some years older, the first citation I can find is to a song from Thomas Odell’s (1691-1749) ballad opera The Patron (1729), where the tune for the lyric is given as that of “Why, Soldiers, Why”, which is the beginning of the second verse. (For the first two verses, see: https://tunearch.org/wiki/Annotation:Why_Soldiers_Why%3F The tune may be older yet, as there’s a 1712 broadside entitled “The Duke of Marlborough’s Delight” set “to a new tune” which has similar lyrics—see the text here: http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/static/images/sheets/20000/16153.gif You can hear the tune to “Why, Soldiers, Why” here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-VxlkhsOcRI )

The glass I want to talk about is, in fact, both related to the lyric, with its “Let mirth and wine abound”, and another kind of glass entirely.

When the dwarves overwhelm Bilbo’s house, in the first chapter of The Hobbit (“An Unexpected Party”—which is, in fact, a pun—JRRT admits, in a letter to Deborah Webster 25 October, 1958, Letters, to having a simple, hobbit sense of humor—not only is a party a festivity—although this one, for Bilbo was far from it—but, in older English, “party” can also mean “a person”—so that “unexpected party/person is presumably Gandalf, as it’s in the singular),

(Alan Lee)

they mock his discomfort in a clean-up song which begins:

“Chip the glasses and crack the plates!”

and this made me wonder: The Hobbit, like The Lord of the Rings, is set in a pre-industrial—really, medieval—world: what kind of glasses might these be?

Glass, as a material, is much older than the western Middle Ages. As you might expect from something which may have originated in the middle of the 3rd millennium BC (2500BC?—there’s lots of on-line discussion, but see, for example: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/a-brief-scientific-history-of-glass-180979117/ ), there has been much scholarly debate on the subject, but let’s go with that rough date for the present.

A combination of silica sand,

lime,

(powdered, of course)

and sodium carbonate,

(plus lots of other elements for various additional properties—see for more: http://www.historyofglass.com/glass-making-process/glass-ingredients/ )

when heated to about 2400 degrees Fahrenheit (about 1315C), produces a moldable, shapeable liquid.

(For an experiment on making early glass, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lg7kZpTVoms This is from a YouTube series called “How to Make Everything” and, if you’re like me, interested in all early technologies, definitely recommended. There’s an interesting suggestion there, as well, that glass may have been an accidental byproduct of early metal-working.)

The first surviving glass seems to be beads–

these are Mesopotamian, but found in a grave in Denmark, showing just how extensive early trade networks were.

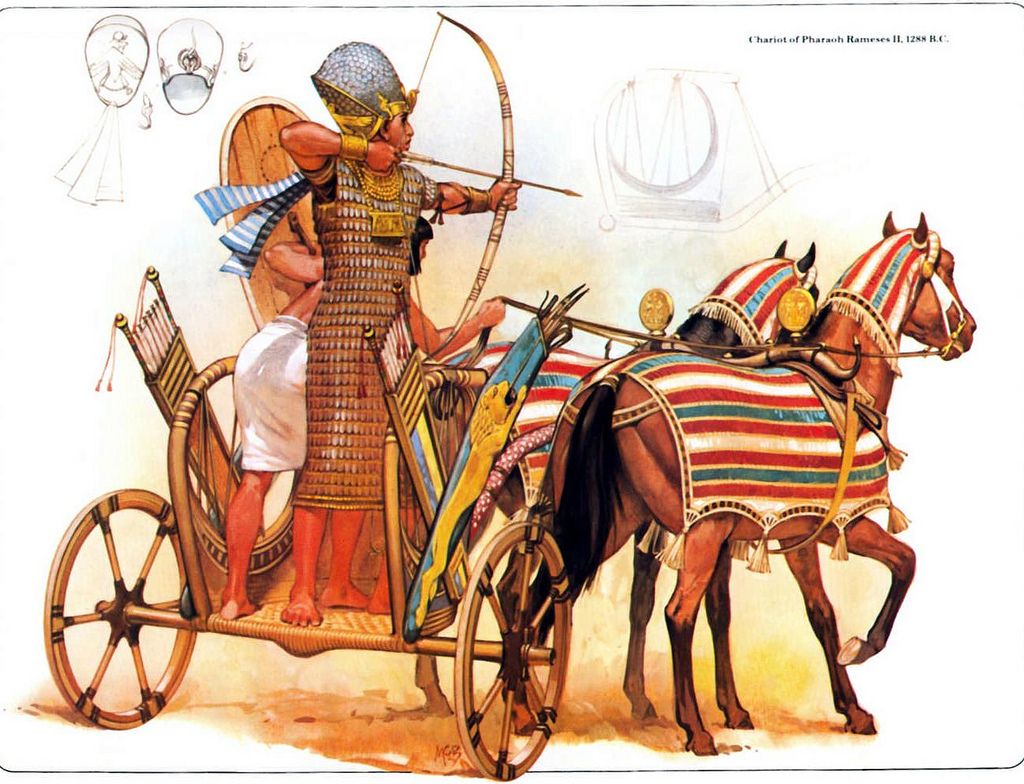

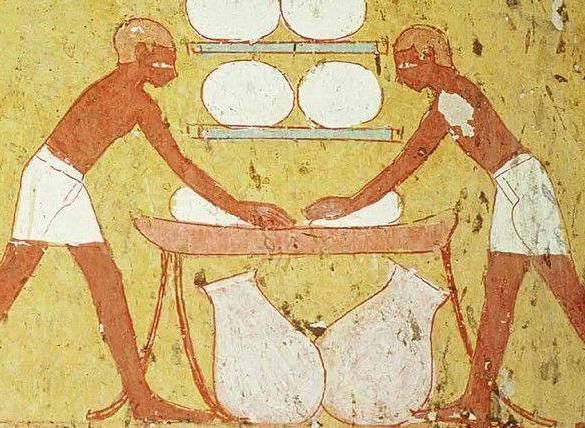

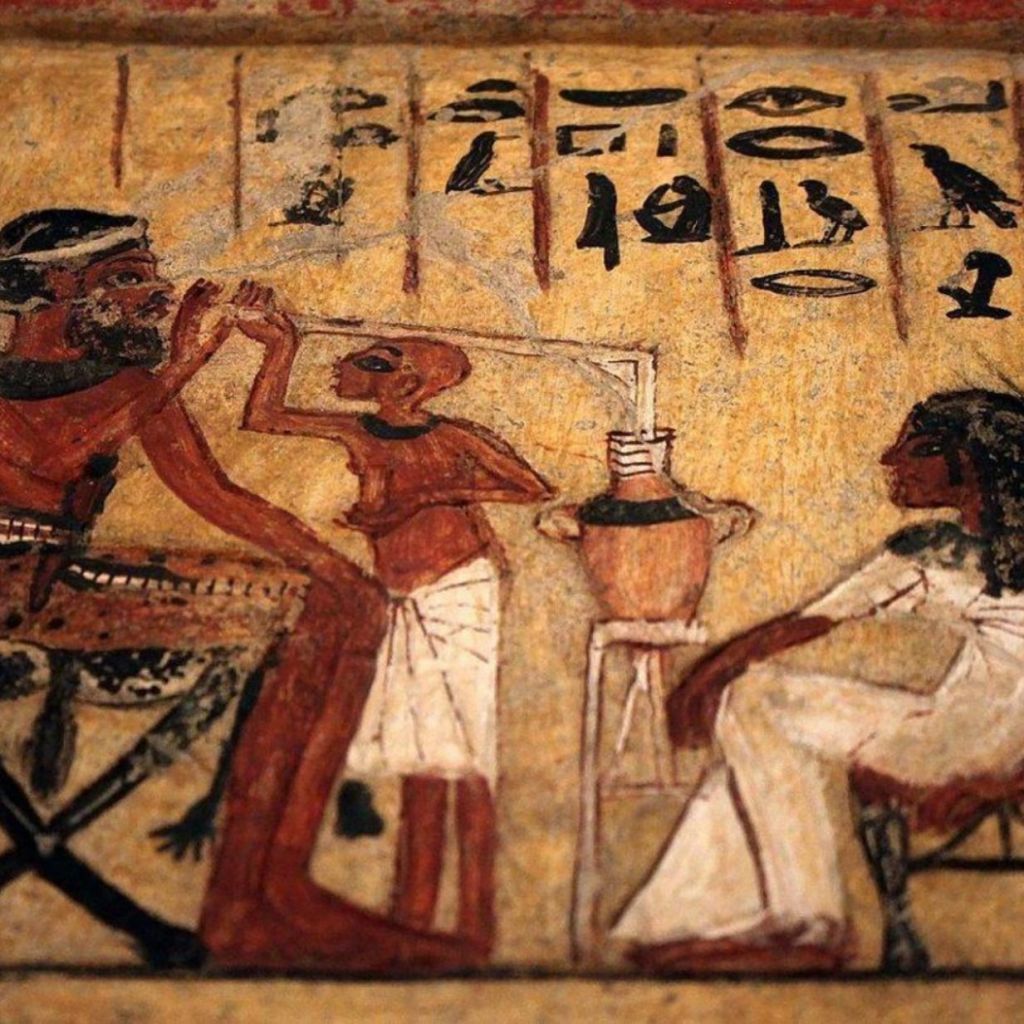

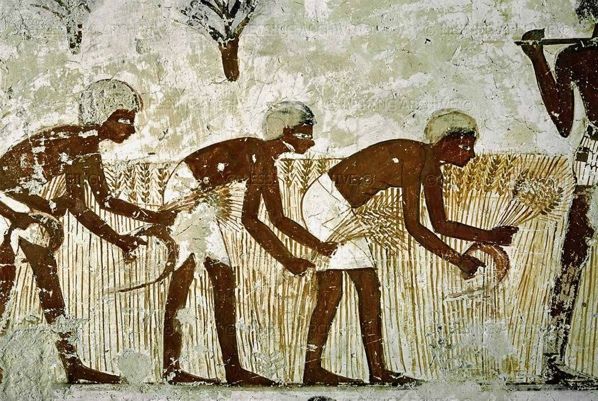

The Egyptians went into the glass business at some point,

and, eventually, the later Assyrians even produced the first known glass-making manual in the reign of King Ashurbanipal (reigned 669-631BC)—you can read about it here: https://historyofknowledge.net/2018/12/05/you-us-and-them-glass-and-procedural-knowledge-in-cuneiform-cultures/ and read a translation of the cuneiform tablets on which it was written here: https://www.nemequ.com/texts )

The Romans produced some rather amazing creations in glass,

as well as the first window glass.

(For how Romans made window glass, see: http://www.theglassmakers.co.uk/archiveromanglassmakers/articles.htm#No This is actually a small collection of interesting articles. Scroll to the last to see the specific piece about window glass.)

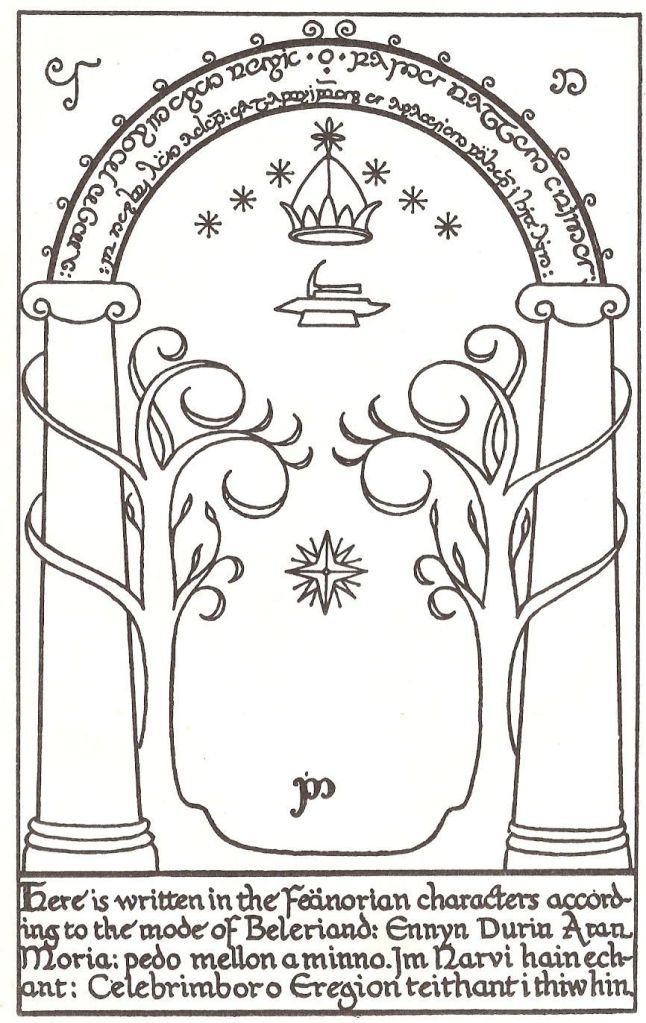

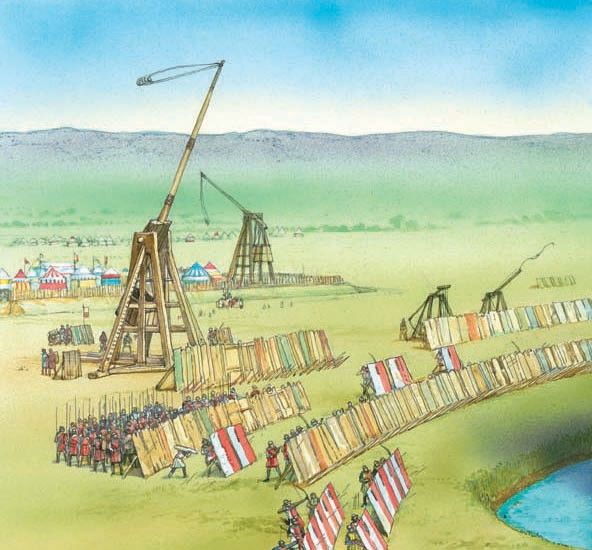

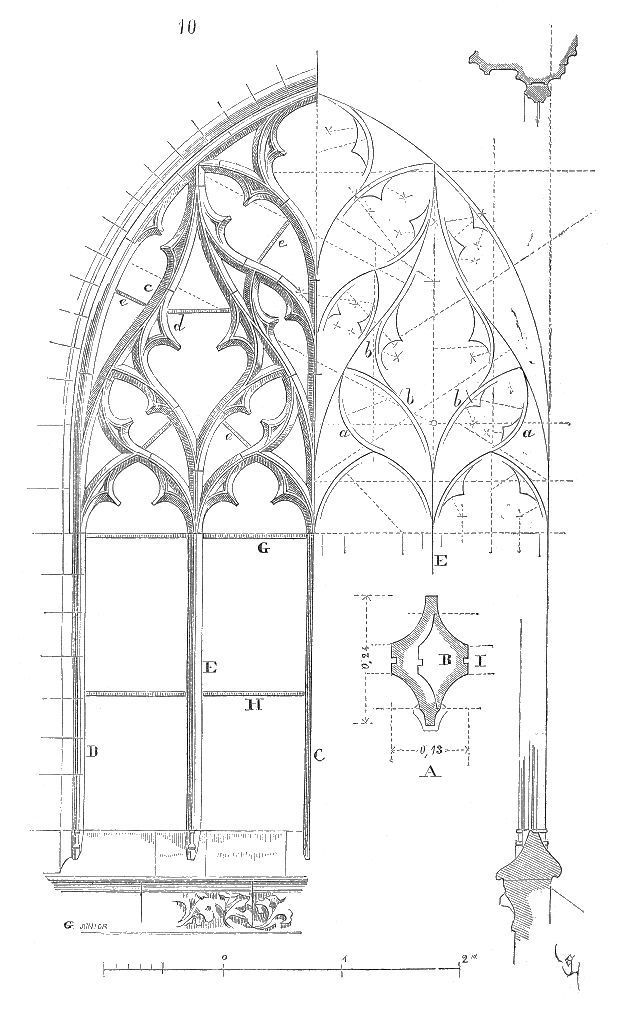

Even after the change in the western Roman empire from imperial rule to Germanic kingdoms and their later successors, the art of glass-making was never lost, but it appears that the older method of making larger panes may have been, since medieval domestic windows used smaller pieces of glass framed in metal, called “mullioning”—

and this was only for the very wealthy. This leads me to wonder about:

“The best rooms were all on the left-hand side (going in), for these were the only ones to have windows, deep-set round windows looking over his garden, and meadows beyond, sloping down to the river.” (The Hobbit, Chapter One, “An Unexpected Party”)

(JRRT)

Is this hobbit mullioning? Other buildings in the Shire look to have had ordinary glass windows, as in—

“…some new houses had been built: two-storeyed with narrow straight-sided windows, bare and dimly lit, all very gloomy and un-Shirelike.”

and

“The Shirriff-house at Frogmorton was as bad as the Bridge-house. It had only one storey, but it had the same narrow windows…”

I suspect that what Tolkien had in mind was something like these Victorian railway workers’ houses,

as mentioned earlier:

“Worse, there was a whole line of the ugly new houses all along Pool Side…”

(All of these grim quotations are from The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 8, “The Scouring of the Shire”)

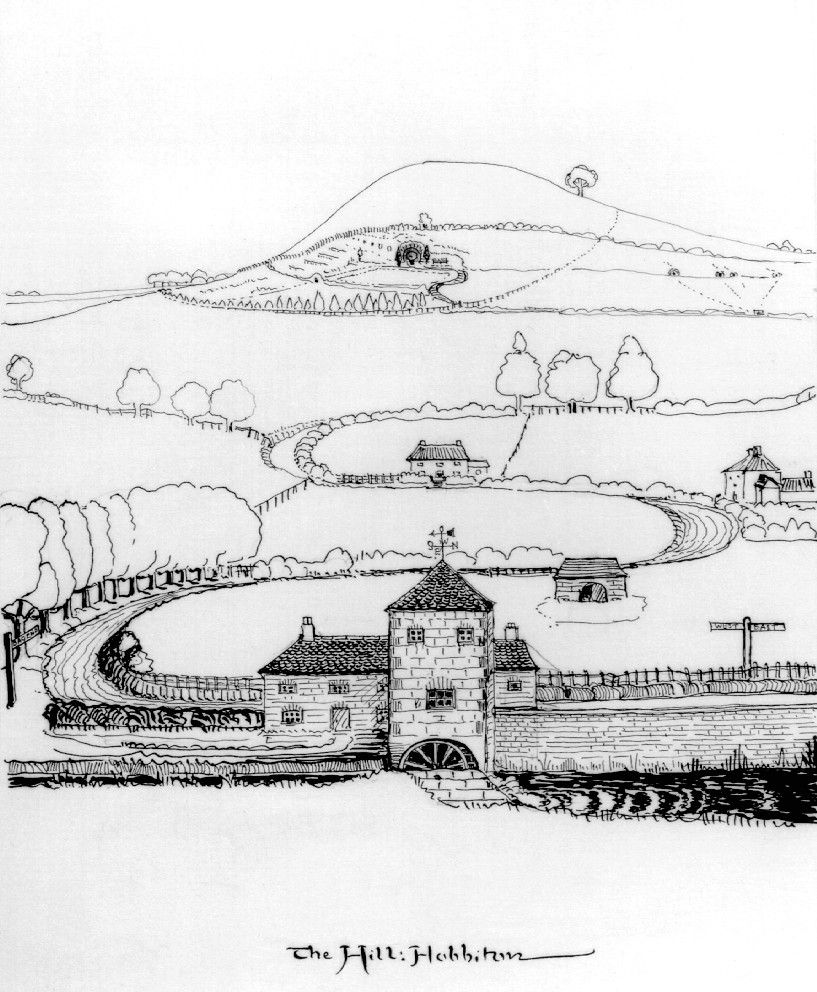

Clearly, “Shirelike” means windows of an entirely different design—and that means round, as Tolkien’s own view towards Bag End shows us—

(JRRT)

(Although you can see, by the way, in this earlier sketch, that Tolkien had not originally decided upon the window-shape consistency of the later illustration, or on the true meaning of “Shirelike”.)

But, though a window plays an important part in recruiting a crucial member of the Fellowship of the Ring:

“Suddenly he stopped as if listening. Frodo became aware that all was very quiet, inside and outside. Gandalf crept to one side of the window. Then with a dart he sprang to the sill, and thrust a long arm out and downwards. There was a squawk, and up came Sam Gamgee’s curly head hauled by one ear.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 2, “The Shadow of the Past”)

(Artist? I’m always glad to credit one, but I’m stumped here.)

the glasses which the dwarves threaten to chip are clearly of the drinking variety.

I imagine that the glasses in the Tolkien household looked like this

or, for more formal occasions, like this

and what JRRT drank from at The Eagle and Child (aka “The Bird and Baby”) or The Lamb and Flag would have been something like this–

But that’s the first half of the 20th century.

Could we see this actual medieval glass as a model?

It seems awfully dainty and, remembering the dwarves’ demands for what seems like endless rounds of food and drink, however, perhaps it wasn’t chipped glasses which Bilbo should worry about at all, but dented tankards!

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

When necessary, sing quietly to yourself, “Ho, ho, ho, To the bottle I go…”,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

As you can tell, the history of glass—and windows—is long and complicated.

See this for more on glass: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_glass

And this on windows: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Window