Tags

Beowulf, Bilbo, bilbo-burglar, Dragons, Dwarves, Fafnir, Fantasy, Hippogriff, Hoard, Marx Brothers, quest, Sigurd, Smaug, The Hobbit, The Reluctant Dragon, Thorin, Tolkien

As always, dear readers, welcome.

I think that I’ve always been a fan of the Marx brothers.

Their lack of respect for pompous men in silk hats,

opera-goers who are only interested because it gives them social status,

and self-important artists,

among many others, and their creative methods of deflating such people,

have always cheered me immensely.

There is another side to their comedy, however, which means just as much to me: their endless play with words, delivered always deadpan and with perfect timing—not to mention absolute absurdist nonsequiturism.

Take, for example, this fragment from The Cocoanuts, their first surviving film, from 1929. It’s set during the 1920s Florida land boom (read about that here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florida_land_boom_of_the_1920s ) and, in this scene, “Mr. Hammer”, Groucho, is explaining the layout of a real estate plot to “Chico”, Chico,

saying, at one point:

“Groucho: Now, here is a little peninsula, and, eh, here is a viaduct leading over to the mainland.

Chico: Why a duck?

Groucho: I’m all right, how are you? I say, here is a little peninsula, and here is a viaduct leading over to the mainland.

Chico: All right, why a duck?

Groucho: I’m not playing ‘Ask Me Another’, I say that’s a viaduct.

[Ask Me Another was originally an early 1927 equivalent of “Trivia”. You can read about it here: https://www.thefedoralounge.com/threads/how-do-you-play-ask-me-another.62135/ and here’s a copy—

Chico: All right! It’s what…why a duck? Why no a chicken?

Groucho: I don’t know why no a chicken—I’m a stranger here myself. All I know is that it’s a viaduct. You try to cross over there a chicken and you’ll find out why a duck.”

(For the entire script see: https://www.marx-brothers.org/marxology/cocoanuts-script.htm )

By the same kind of logic which produced this, I found myself thinking about The Hobbit: and hence the title of this posting: why a dragon?

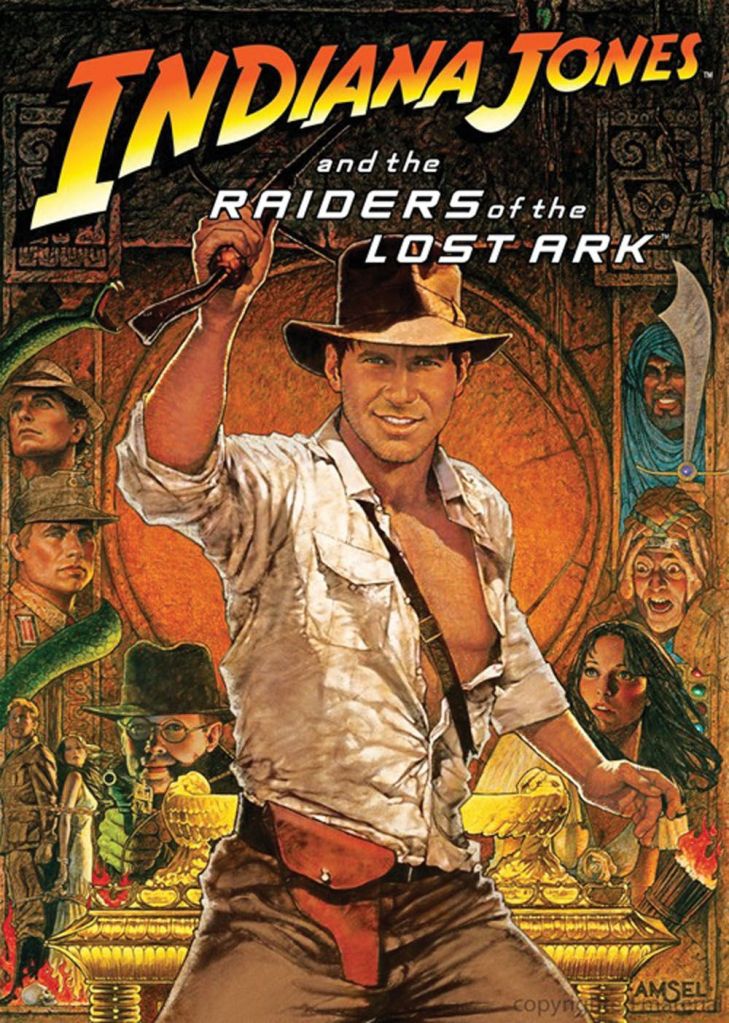

The plot of The Hobbit is, basically, a quest: a journey with a goal.

Quests are a familiar form of adventure story and still common—just think about Indiana Jones, with his Lost Ark

and his Holy Grail, for example.

Indiana has to travel to Tibet and Egypt and to an unnamed island in the Mediterranean for the Ark and to Germany and Turkey for the Grail.

Although Thorin doesn’t mention the travel in his “mission statement”, much of the story will be about travel, from the Shire to the Lonely Mountain and back again,

to reach the dwarves’ goal, as stated in the first chapter by Thorin:

“But we have never forgotten our stolen treasure. And even now, when I will allow we have a good bit laid by and are not so badly off…we still mean to get it back, and to bring our curses home to Smaug—if we can.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 1, “An Unexpected Party”)

The goal, then, is in two parts:

1. to regain the treasure taken from the dwarves by the dragon

2. to take revenge upon said dragon

Because they are aware that the dragon can be lying on top of the treasure (“Probably”, says Thorin, “for that is the dragons’ way, he has piled it all up in a great heap far inside, and sleeps on it for a bed.”), it’s clear that 1 and 2 have to be dealt with as a sequence: no getting the treasure without getting rid of the dragon.

Which brings us back to my title. Indiana Jones commonly has Nazis (and eventually Communists and even Neo-Nazis) as opponents,

these being the characters who compete for his goal and stand in the way of his achieving his quest.

Tolkien was a medievalist, writing a sort of fairy tale, so what would be his equivalent and why?

We know that Tolkien had been interested in dragons since far childhood—at least the age of 6, when he tried to write a poem about a “green, great dragon” (to the Houghton Mifflin Company [summer, 1955?], Letters, 321—JRRT tells a somewhat different version of this to W.H. Auden in a letter of 7 June, 1955, Letters, 313) and he confesses to an early love for them in his lecture “On Fairy-Stories” where he mentions Fafnir and Sigurd, suggesting that he may have had read to him or had read for himself from Andrew Lang’s The Red Fairy Book, 1890, the last chapter of which is “The Story of Sigurd”, and since, elsewhere, he mentions “Soria Moria Castle”, which is the third story in the same book.

(Your copy is here: https://archive.org/details/redfairybook00langiala/redfairybook00langiala/ )

Fafnir, the dragon in the Sigurd story, is described as, having killed his own father:

“he went and wallowed on the gold…and no man dared go near it.” (“The Story of Sigurd”, 360)

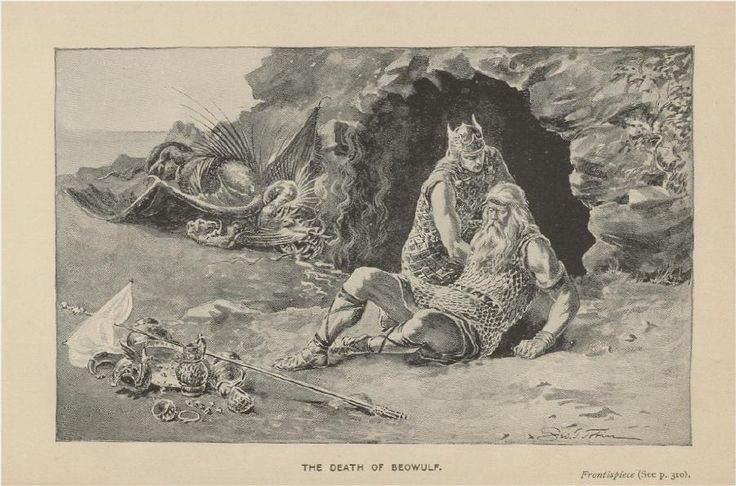

The next major dragon story with which Tolkien was probably involved saw the same draconic behavior, as, in Beowulf, we’re told that the unnamed dragon, having discovered a hoard in a tumulus:

“This hoarded loveliness did the old despoiler wandering

in the gloom find standing unprotected, even he who filled

with fire seeks out mounds (of burial), the naked dragon of

1915

fell heart that flies wrapped about in flame: him do earth’s

dwellers greatly dread. Treasure in the ground it is ever his

wont to seize, and there wise with many years he guards the

heathen gold – no whit doth it profit him.”

(from JRRT’s draft translation of 1920-26 in Christopher Tolkien’s 2014 publication)

Traditionally, then, dragons and gold go together—and, as JRRT admitted in a letter to the Editor of the Observer, “Beowulf is among my most valued sources” (letter to the Editor of the Observer, printed in the Observer, 28 February, 1938, Letters, 41)

There is a very interesting twist in Tolkien’s version of the story, however.

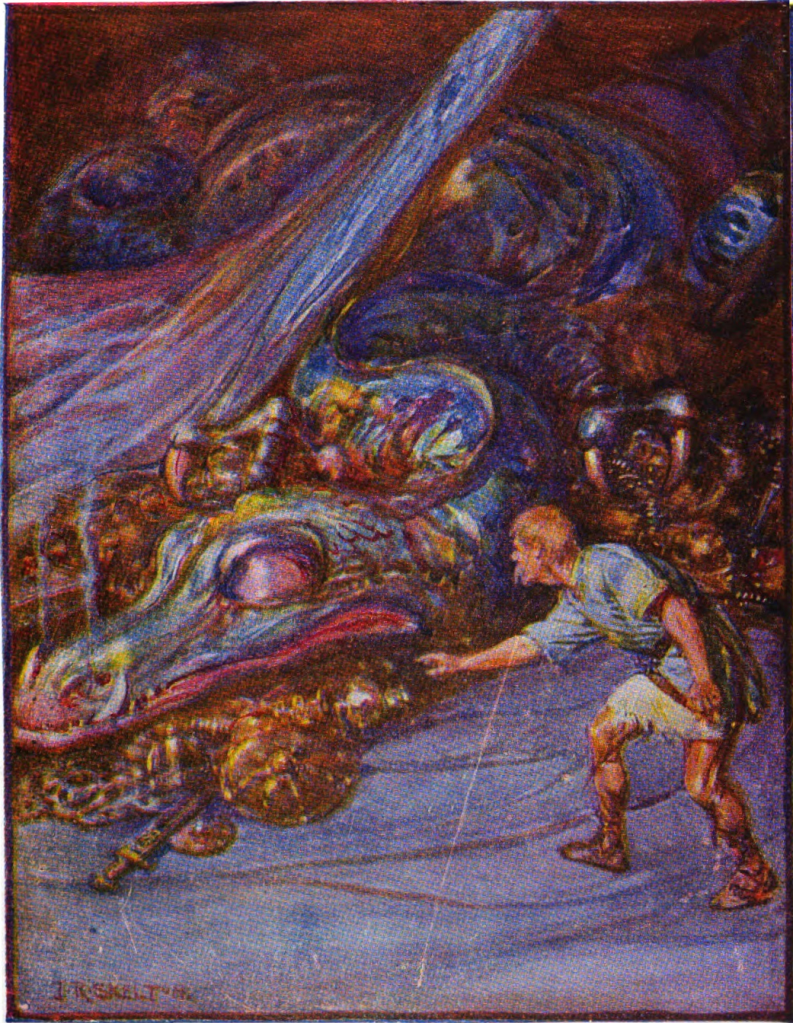

By lying in a pit below the dragon, Sigurd slays Fafnir

and Beowulf, along with his companion (and successor), Wiglaf, make an end of the nameless dragon,

(This is a pretty silly version, with costumes and armor which look like they came from the original production of Der Ring des Nibelungen, but finding a depiction of the two attacking the dragon has seemed surprisingly difficult.)

but, in The Hobbit, although we have the traditional dragon on the traditional hoard, we don’t have the traditional dragon-slayer, a fact underlined by Thorin’s “to bring our curses home to Smaug, if we can”.

This has always struck me as the potential weak point in the quest: to travel hundreds of miles through dangerous territory filled with trolls, goblins, wolves, hostile elves, and even giant spiders, to come to a mountain inhabited by a fearsome dragon—but to have no plan in mind as to how to deal with it, especially when the other half of the plan—to get back the dwarvish treasure—requires somehow eliminating the current guardian of that treasure.

(JRRT)

Faced with that possible weak point, so much now may appear to have a certain haphazard happenstance about it, the kind of attempted slight-of-hand which indicates an author who hasn’t the skill to create a narrative in which every element seems to fall naturally into place, and this might make us question the finding of the Ring, the convenient rescue at Lake-town, even the ray of sun which indicates the opening to the back door of the Lonely Mountain (suppose it had been overcast).

But this is where the burglar comes in—and the story of Sigurd once more.

It seems that Bilbo was not Gandalf’s first choice for the quest when he came to visit him.

(the Hildebrandts)

Thorin has just mentioned the inconvenient dragon and the awkwardness of his sudden appearance, to which Gandalf replies:

“That would be no good…not without a mighty Warrior, even a Hero. I tried to find one; but warriors are busy fighting one another in distant lands, and in this neighbourhood heroes are scarce, or simply not to be found.”

And he continues:

“That is why I settled on burglary—especially when I remembered the existence of a Side-door. And here is our little Bilbo Baggins, the burglar, the chosen and selected burglar.”

Bilbo’s first attempt at burglary: picking a troll’s pocket,

(JRRT)

almost ends in disaster, but, with the eventual aid of the Ring, he even manages, first, to steal from Smaug, in a direct echo of Beowulf,

(artist? So far, I haven’t seen one credited.)

and then to confront Smaug in his lair and escape, at worst, with only a singeing.

(JRRT)

So far, it’s been burglary, with some help from the Ring, but then the Sigurd story comes in.

You’ll remember that, although the version in The Red Fairy Book doesn’t say so, it was clear that the vulnerable part of the dragon Fafnir was its underside, which is why Sigurd hid in a pit so that, when the dragon crawled over it, Sigurd could stab him in that unprotected underbelly.

Using his burglarious skills, as well as a fluent tongue, Bilbo actually persuades Smaug unknowingly to expose his own vulnerability:

“ ‘I have always understood…that dragons were softer underneath, especially in the region of the—er—chest; but doubtless one so fortified has thought of that.’

The dragon stopped short in his boasting. ‘Your information is antiquated,’ he snapped. ‘I am armoured above and below with iron scales and hard gems. No blade can pierce me.’”

And the smooth-tongued burglar actually flatters Smaug into rolling over, exposing “…a large patch in the hollow of his left breast as bare as a snail out of its shell”.

What to do with this potentially deadly piece of information requires the reverse of the Sigurd story.

In that story, Sigurd, having killed Fafnir, has been asked by his mentor, Regin, to roast the dragon’s heart and serve it to him. In the process, Sigurd burns a finger, puts it in his mouth, and suddenly understands that all of the birds above him are talking about him and telling him to beware of Regin.

In The Hobbit, the opposite happens: the thrush who had tapped the snail

(Alan Lee)

and therefore set off the chain of events which revealed the back door to the Lonely Mountain to Bilbo and the dwarves, overhears Bilbo telling the dwarves about Smaug’s vulnerable spot, which he then conveys to Bard the Archer, who is then the dragon-slayer

(Michael Hague—one of my favorite Hobbit illustrators)

needed to dispose of the one-time guardian of the hoard.

And so the dragon is disposed of—but he has one more use in the story: as a negative model.

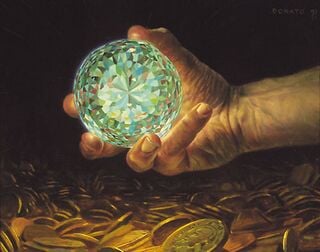

Although Thorin has led the quest to retrieve the dwarves’ treasure, it seems that there’s only one which he craves, the Arkenstone,

(Donato Giancola)

and it’s clear that, in its pursuit, he becomes much like the Smaug who once reacted almost hysterically when he sensed that something was missing from his hoard:

“Thieves! Fire! Murder!…His rage passes description—the sort of rage that is only seen when rich folk that have more than they can enjoy suddenly lose something that they have long had but have never before used or wanted.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 12, “Inside Information”)

Here’s his dwarvish parallel:

“ ‘For the Arkenstone of my father,’ he said, ‘is worth more than a river of gold in itself, and to me it is beyond price. That stone of all the treasure I name unto myself, and I will be avenged on anyone who finds it and withholds it.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 16, “A Thief in the Night”)

And, when he finds that Bilbo has taken it as a way to make peace between the dwarves, the elves, and the Lake-town men, Thorin almost does take revenge:

“ ‘You! You!’ cried Thorin, turning upon him and grasping him with both hands. ‘You miserable hobbit! You undersized—burglar!…By the beard of Durin! I wish I had Gandalf here! Curse him for his choice of you! May his beard wither! As for you I will throw you to the rocks!’ he cried and lifted Bilbo in his arms.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 17, “The Clouds Burst”)

So why a dragon?

First, to Tolkien the medievalist, gold and dragons go together: a quest for treasure needs a particularly powerful enemy and the dragon of Beowulf, who actually fatally wounds Beowulf,

who had previously defeated two terrible opponents in Grendel and his mother, provides a strong model.

Second, JRRT had, from childhood, a long-standing interest in dragons—he’ll return to them in his 1938/49 novella, “Farmer Giles of Ham”, where the practical farmer eventually not only tames the dragon, Chrysophylax (“Goldwatchman”, perhaps), but makes him disgorge much of his treasure—this time by doing nothing more than outfacing him and threatening him with his sword, “Tailbiter”.

It’s interesting, by the way, that, although, in “The Story of Sigurd”, the dragon talks, he has only one short speech: a curse on anyone who touches his gold, whereas, in perhaps the greatest draconic influence upon Tolkien, Beowulf, another wyrm who enjoys lying on a hoard, is mute.

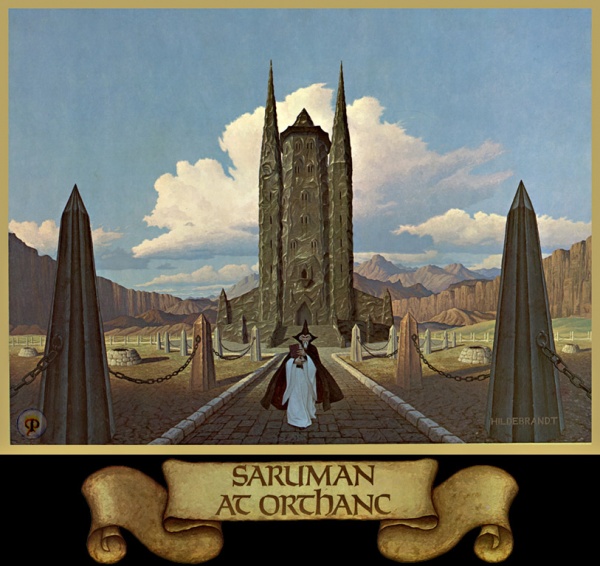

Smaug, in The Hobbit, however, is not only positively talky, but, like Saruman in The Lord of the Rings, his voice and manner have their own dangerously persuasive power, at one point in his conversation with Bilbo even beginning to seed Bilbo’s mind with doubts about the dwarves Bilbo accompanies (The Hobbit, Chapter 12, “Inside Information”).

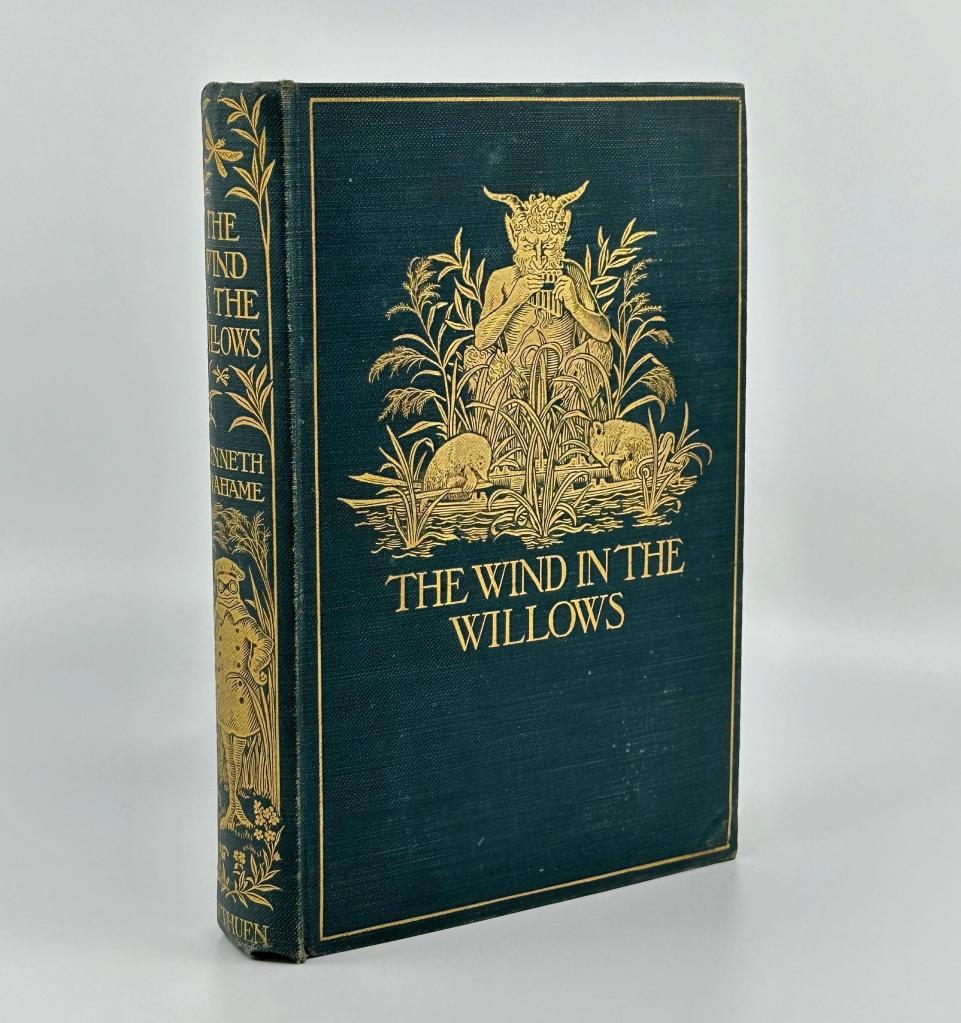

Chrysophylax, in “Farmer Giles of Ham” is even more talkative than Smaug, and I wonder about the model for these chatty beasts. Tolkien was a great fan of Kenneth Grahame (1859-1932) and of his well-known children’s book, The Wind in the Willows (1908),

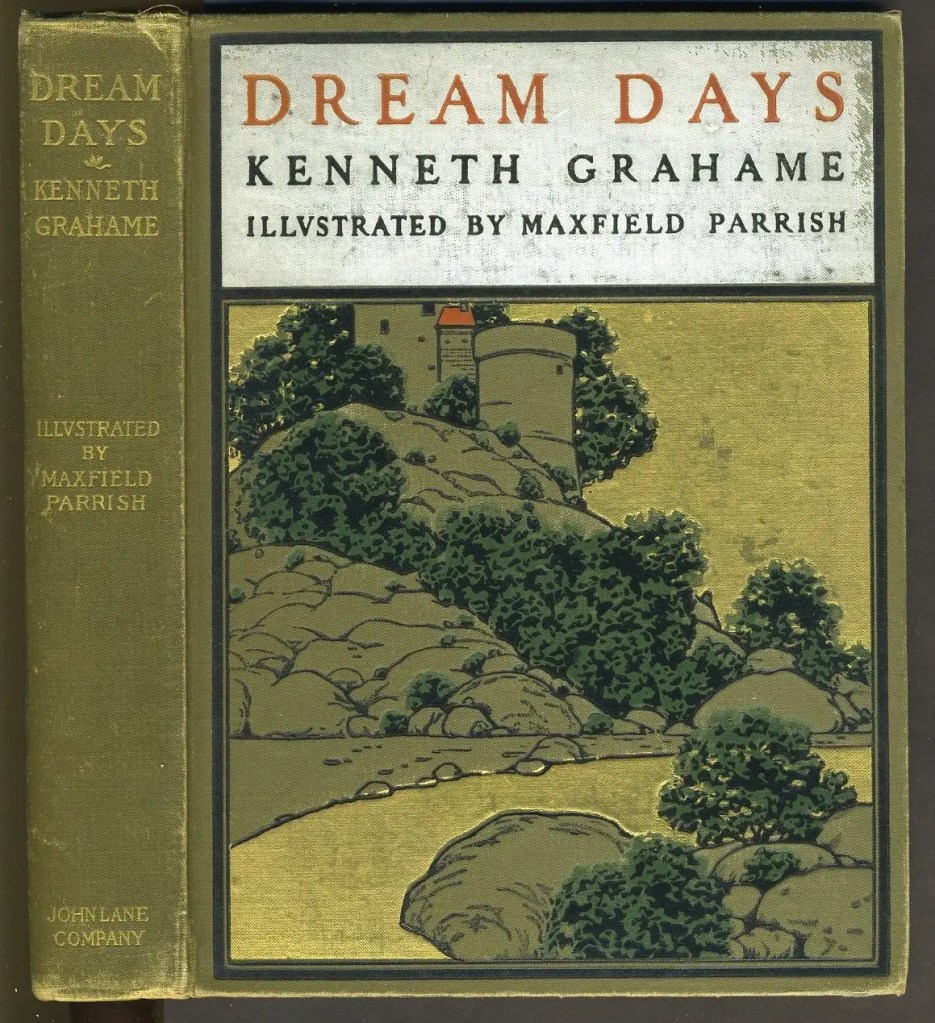

mentioning in a letter to Christopher Tolkien that Elspeth Grahame, Grahame’s widow, is publishing a book with other stories about the main characters of The Wind in the Willows, a book which JRRT is very eager to obtain (letter to Christopher Tolkien, 31 July, 1944, Letters, 128). In 1898, Grahame published a collection of stories, Dream Days,

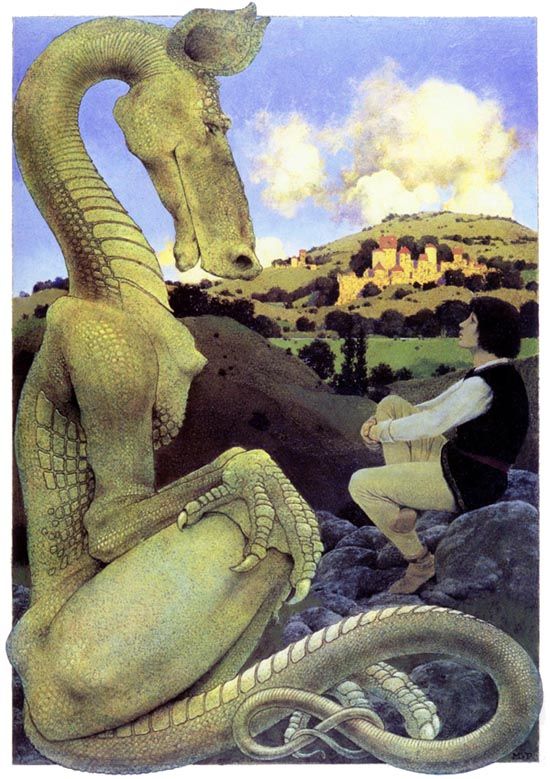

which included “The Reluctant Dragon”, in which we see another very loquacious beast,

(from the original book, illustrated by Maxfield Parrish)

(I couldn’t resist including E.H. Shepard’s 1938 version)

but rather more like the ultimately rather timid dragon of “Farmer Giles” than the grim and mute creature of Beowulf or the more-than-a-little-pleased-with-himself Smaug, but, in his garrulousness, could he have been a model for Smaug? (You can make your own comparison with: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/35187/35187-h/35187-h.htm )

To this we add perhaps not a model, but a parallel: Thorin as becoming a kind of dwarvish dragon in his obsession with the Arkenstone. Fafnir dies with a curse, however, the Beowulf beast dies killing Beowulf, and Smaug dies destroying Lake-town,

but, in his own last moments, Thorin escapes such a poisonous model, saying to Bilbo:

“Farewell, good thief…I go now to the halls of waiting to sit beside my fathers, until the world is renewed. Since I leave now all gold and silver, and go where it is of little worth, I wish to part in friendship from you, and I would take back my words and deeds at the Gate.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 18, “The Return Journey”)

(Darrell Sweet—you can read a little about him here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Darrell_K._Sweet )

And so “Why a dragon?”—and not “Why No a Hippogriff?”

(artist? so far, I haven’t found one–a pity, too, as it’s quite a splendid illustration and I’ll love to mention the author!)

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

Remember not to laugh at live dragons,

And remember, as well, that there’s

MTCIDC

O