As always, dear readers, welcome.

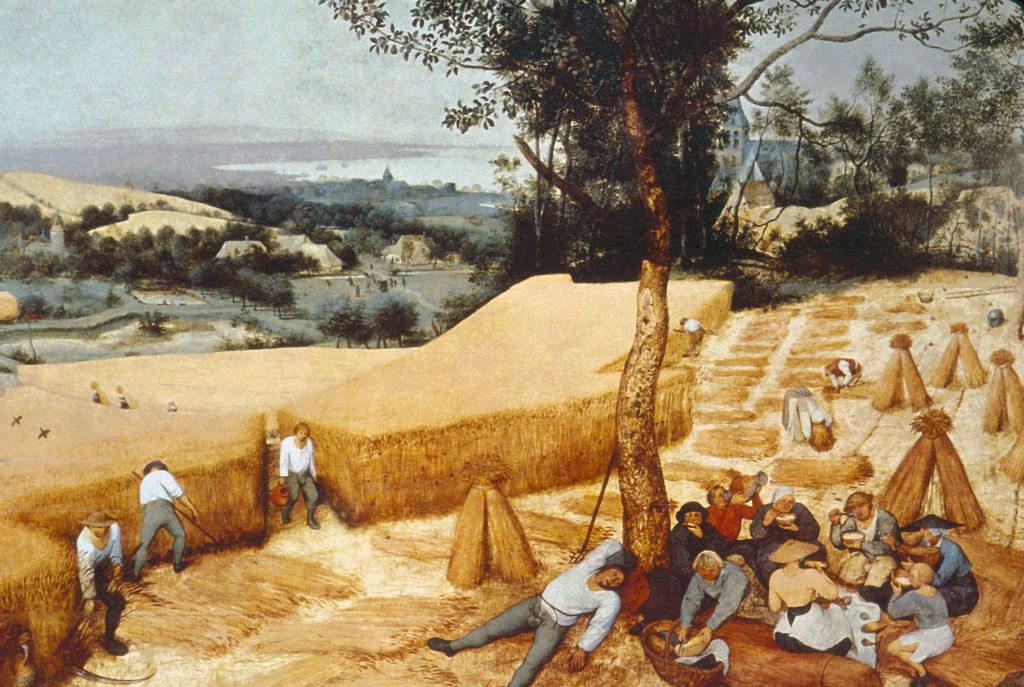

“The hallway smelt of boiled cabbage and old rag mats. At

one end of it a coloured poster, too large for indoor display,

had been tacked to the wall. It depicted simply an enor-

mous face, more than a metre wide: the face of a man of

about forty-five, with a heavy black moustache and rugged-

ly handsome features. Winston made for the stairs. It was no

use trying the lift. Even at the best of times it was seldom

working, and at present the electric current was cut

off during daylight hours. It was part of the economy drive

in preparation for Hate Week. The flat was seven flights up,

and Winston, who was thirty-nine and had a varicose ulcer

above his right ankle, went slowly, resting several times on

the way. On each landing, opposite the lift-shaft, the poster

with the enormous face gazed from the wall. It was one of

those pictures which are so contrived that the eyes follow

you about when you move. BIG BROTHER IS WATCHING

YOU, the caption beneath it ran.” (George Orwell, 1984, Part One, Chapter 1)

This is the second paragraph in the first chapter of “George Orwell”’s (aka Eric Blair, 1903-1950) 1948 dystopian novel, 1984. It’s an extremely thoughtful, well-written book, but its view of the future seems so hopeless and grim that it’s not easy to read—you can do it here, however: https://archive.org/details/GeorgeOrwells1984

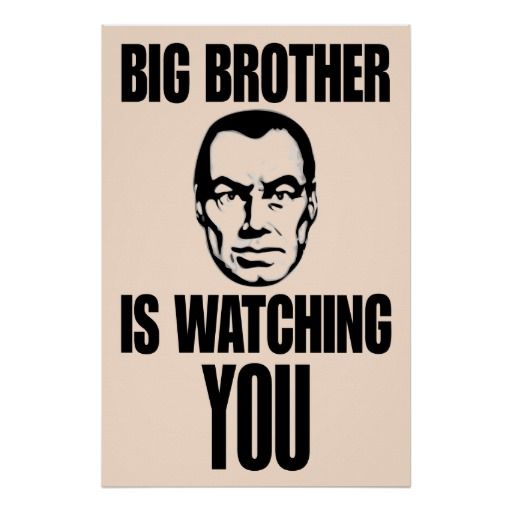

I’ve been interested in that poster.

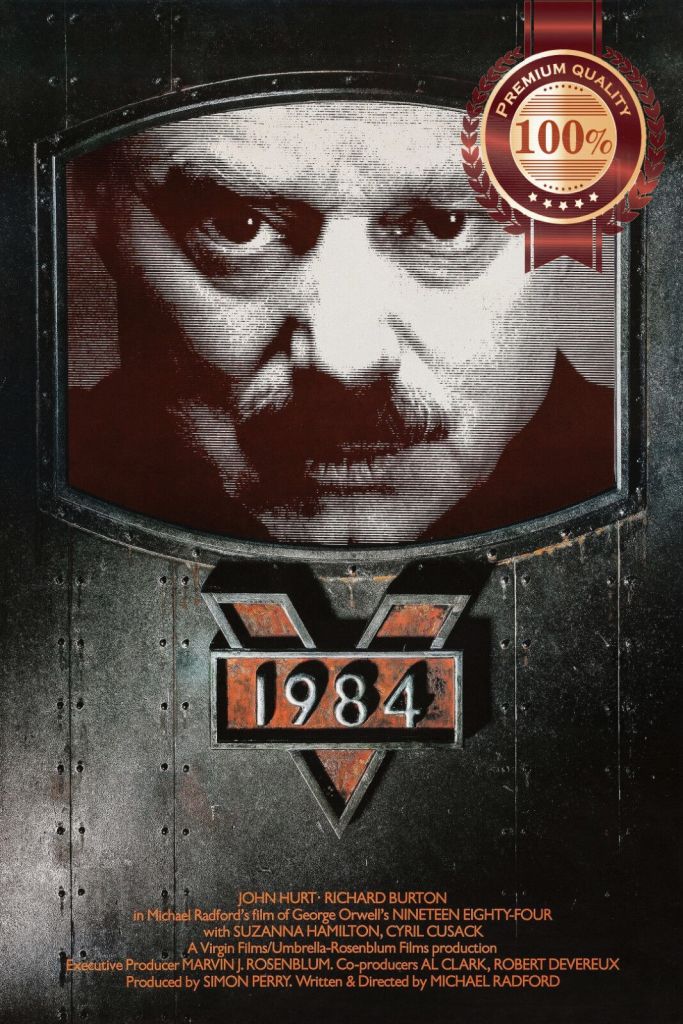

The first film made from the book, in 1956, doesn’t appear to have believed the kind of image of “Big Brother” which Orwell described—

nor does the second film, from, appropriately enough, 1984—

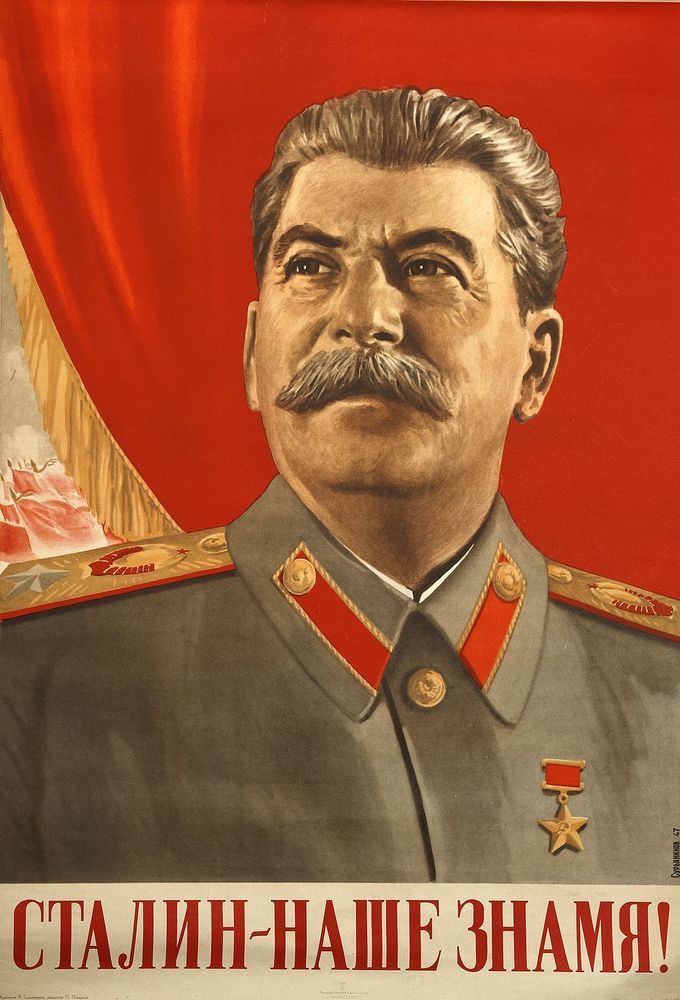

The first is lacking that mustache (and looks more like a man in a staring contest) and the second to me appears to be the image of someone earnestly trying to sell us something. I wonder if what Orwell (who loathed Stalinist Russian and who used it as a model for his future Britain) actually had in mind was something like this—

combined with this—

(the British Field Marshall and Secretary of State for War, H.H. Kitchener, 1850-1916, on probably the most influential recruiting poster of the Great War/WW1)

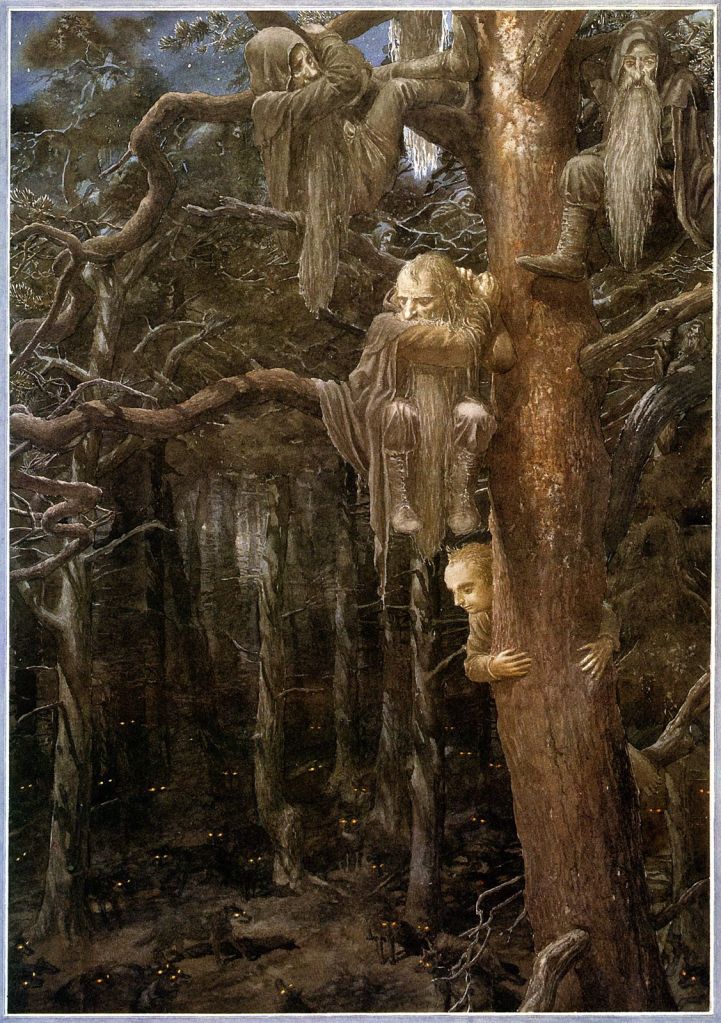

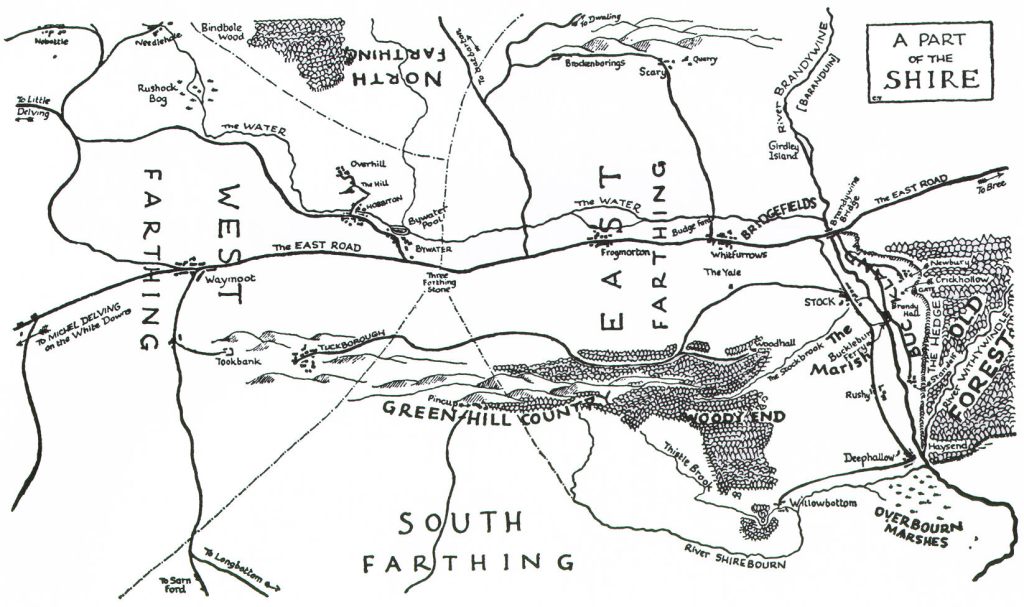

The stare—a kind of commanding gaze—is clearly very important. As Orwell tells us: “It was one of those pictures which are so contrived that the eyes follow you about when you move”, which made me immediately think about Sauron as he appears in The Lord of the Rings—or, rather, doesn’t appear in actual physical form, but is only represented by what Frodo sees in Galadriel’s Mirror:

“But suddenly the Mirror went altogether dark, as dark as if a hole had opened in the world of sight, and Frodo looked into emptiness. In the black abyss there appeared a single Eye that slowly grew, until it filled nearly all the Mirror. So terrible was it that Frodo stood rooted, unable to cry out or to withdraw his gaze. The Eye was rimmed with fire, but was itself glazed, yellow as a cat’s, watchful and intent, and the black slit of its pupil opened on a pit, a window into nothing.”

(an actual yellow cat’s eye)

This is powerful enough, but then—

“Then the Eye began to rove, searching this way and that; and Frodo knew with certainty and horror that among the many things that it sought he himself was one.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 7, “The Mirror of Galadriel”)

When, much later in the story, Pippin makes the mistake of looking into Saruman’s Palantir, he discovers just how powerful that gaze can be:

“ ‘I, I took the ball and looked at it…and I saw things that frightened me. And I wanted to go away, but I couldn’t. And then he came and questioned me; and he looked at me, and, and, that is all I remember…Then suddenly he seemed to see me, and he laughed at me. It was cruel. It was like being stabbed with knives…Then he gloated over me. I felt I was falling to pieces…’ “ (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 11, “The Palantir”)

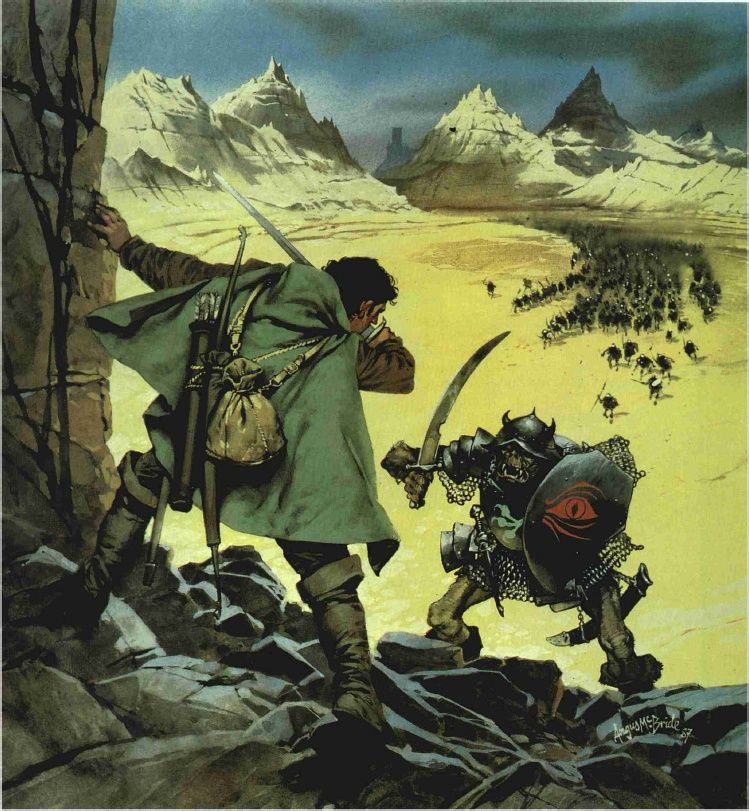

Just like the eyes of Big Brother, and of Field Marshall Kitchener, then, Sauron’s eye radiates authority and sends the same signal: “Sauron is watching YOU”, which is why it appears even on the equipment of Sauron’s orcs—who would dare to flinch or fail when Sauron may actually be watching you personally?

(Angus McBride)

It is the badge, then, of never-sleeping watchfulness.

We know, from the narrator, that Saruman had plans to imitate Sauron—although he was deceived into thinking that he was doing so:

“A strong place and wonderful was Isengard, and long had it been beautiful…But Saruman had slowly shaped it to his shifting purposes, and made it better, as he thought, being deceived—for all those arts and subtle devices, for which he forsook his former wisdom, and which fondly he imagined were his own, came from Mordor; so that what he made was naught, only a little copy, a child’s model or a slave’s flattery, of that vast fortress, armoury, prison, furnace of great power, Barad-dur, the Dark Tower, which suffered no rival, and laughed at flattery, biding its time, secure in its pride and its immeasurable strength.” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 8, “The Road to Isengard”)

If the all-seeing, ever-watchful Eye was Sauron’s badge, it’s interesting to see what Saruman chose:

“Suddenly a tall pillar loomed before them. It was black; and set upon it was a great stone, carved and painted in the likeness of a long White Hand.”

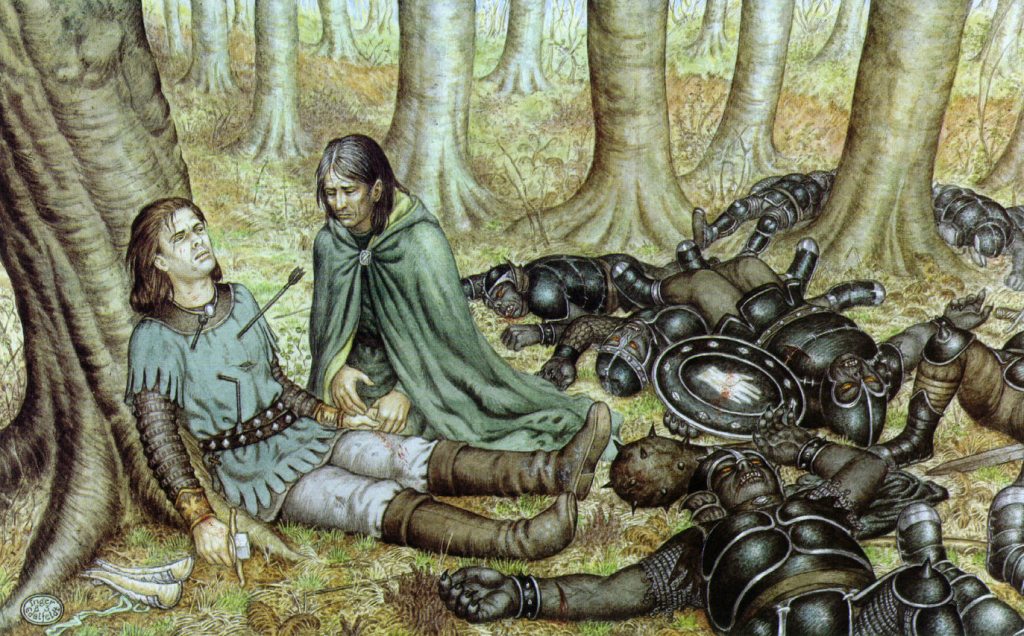

We first meet this sign when Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli are looking through the Orc dead after Boromir’s death:

“There were four goblin-soldiers of greater stature, swart, slant-eyed, with thick legs and large hands. They were armed with short broad-bladed swords, not with the curved scimitars usual with Orcs; and they had bows of yew, in length and shape like the bows of Men Upon their shields they bore a strange device: a small white hand in the centre of a black field; on the front of their iron helms was set an S-rune, wrought of some white metal.” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 1, “The Departure of Boromir”)

(Inger Edelfeldt)

I don’t believe we ever see that “S-rune” again,

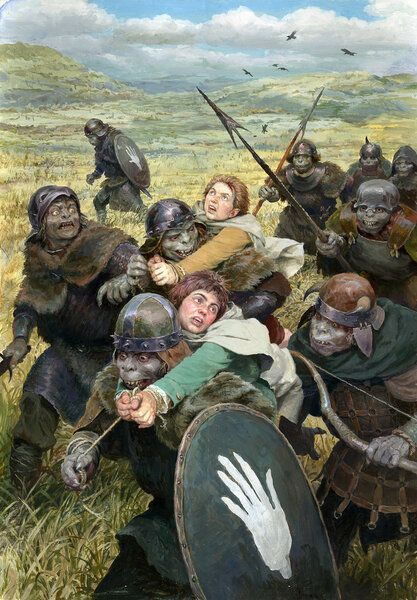

but the White Hand, along with the Eye, will appear as the Orcs carry Merry and Pippin off to the west.

(Denis Gordeev)

But what does it signify? Saruman, as he has become unknowingly corrupted by Sauron, has become “Saruman of Many Colours”, as he explains to Gandalf (see the dialogue between them in The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 2, “The Council of Elrond”), but he began as Saruman the White, and that might explain the color of the hand. On that pillar outside Isengard, the hand, then, might indicate a warning: “Stop. This is the Land of Saruman. Go Back.”, as we imagine the two figures of the Argonath might be indicating by their gesture—

(the Hildebrandts)

This might work for a boundary pillar, but what about those shields? Can we add a second meaning?

Ugluk the captain of the Isengard Orcs might offer a very grim one:

“We are the servants of Saruman the Wise, the White Hand: the Hand that gives us man’s flesh to eat.” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 3, “The Uruk-hai”)

Could this then be another warning: “If you face us, not only will we defeat you, but then we’ll eat you”?

Perhaps a clue to this possibility may be found in a closer examination of that pillar:

“Now Gandalf rode to the great pillar of the Hand, and passed it; and as he did so the Riders saw to their wonder that the Hand appeared no longer white. It was stained as with dried blood; and looking closer they perceived that its nails were red.” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 8, “The Road to Isengard”)

It’s just as well, then, for Pippin when:

“An Orc stooped over him, and flung him some bread and a strip of raw dried flesh…”

that

“He ate the stale grey bread hungrily, but not the meat.”

Thanks, for reading, as ever.

Stay well,

Sometimes it may be good to be a picky eater,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

PS

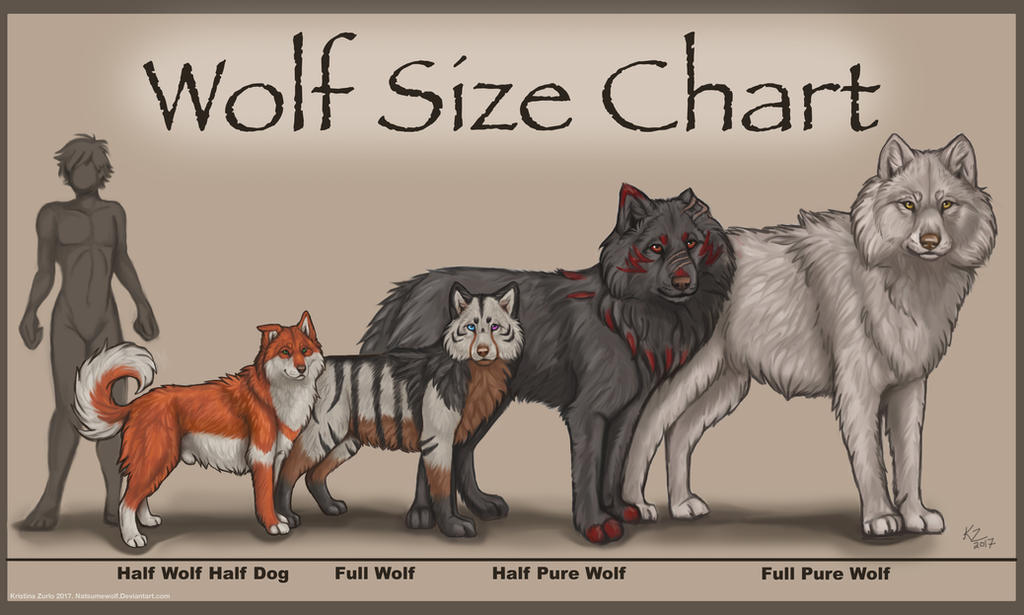

While poking around for white hand images, I found this:

If you’d like to know more about it, see: https://www.shirepost.com/products/white-hand-of-saruman-silver-coin