Tags

books, Conan Doyle, darwin, Fantasy, Fiction, literature, sloths, Tolkien

As always, welcome, dear readers.

Recently, I’ve been watching a very interesting dramatized documentary, “The Voyage of Charles Darwin”.

As the name implies, this includes his 5-year journey around the globe on HMS Beagle,

but goes on to follow his subsequent intellectual development through his gradual understanding of evolution. (You can learn more about him from this rather provocative Britannica entry here: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-Darwin/The-Beagle-voyage )

On his travels along the east coast of South America, Darwin uncovered fossils which puzzled him, including those of a giant ground sloth,

a creature whose (much smaller) tree-dwelling descendant Darwin could see in his own day.

(For more on ground sloths, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ground_sloth ; for modern sloths, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sloth For more on Darwin and fossils, see: https://www.khanacademy.org/partner-content/amnh/human-evolutio/x1dd6613c:evolution-by-natural-selection/a/charles-darwins-evidence-for-evolution )

When I first saw this series, replayed on PBS (Public Broadcasting Service) many years ago, I had come across it by accident—very much an accident because I had, I thought, no interest whatever in science, not having enjoyed the required courses in school (gross understatement). It was so well done, both visually and dramatically, that I was hooked and now, years later, I’ve acquired both an active interest in the history of science as well as my own DVD set of the documentary and am enjoying it even more. It was in my mind, then, when I came across this Tolkien letter to Rhona Beare, an early Tolkien enthusiast, who had written to Tolkien with a number of questions about various details in The Lord of the Rings, including “Did the Witch-king ride a pterodactyl at the siege of Gondor?” to which JRRT replied:

“Yes and no. I did not intend the steed of the Witch-King to be what is now called a ‘pterodactyl’, and often is drawn (with rather less shadowy evidence than lies behind many monsters of the new and fascinating semi-scientific mythology of the ‘Prehistoric’). But obviously it is pterodactylic and owes much to the new mythology, and its description even provides a sort of way in which it could be a last survivor of older geological eras.” (letter to Rhona Beare, 14 October, 1958, Letters, 403)

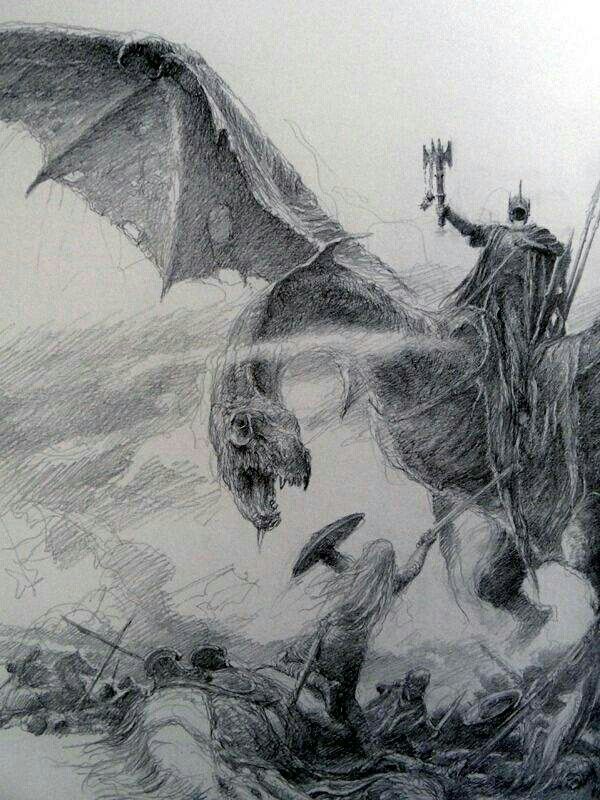

The choice of “steed” Beare andTolkien are referring to is based upon this:

“The great shadow descended like a falling cloud. And behold! It was a winged creature: if bird, then greater than all other birds, and it was naked, and neither quill nor feather did it bear, and its vast pinions were as webs of hide between horned fingers; and it stank. A creature of an older world maybe it was, whose kind, lingering in forgotten mountains cold beneath the Moon, outstayed their day…” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 6, “The Battle of the Pelennor Fields”)

And one can see why a pterodactyl might be tempting—

(Alan Lee)

Those words in Tolkien’s text, “A creature of an older world maybe it was, whose kind, lingering in forgotten mountains cold beneath the Moon…” reminded me of a novel Tolkien may once have read, Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, 1912. In this novel, a group of adventurers gains access to just that: a secluded South American valley, in which various early creatures, including pterodactyls, are still living and, in fact, a young pterodactyl is even brought back to London. Neither Letters nor Carpenter’s biography mentions Conan Doyle or the novel, but the idea of the “older world” and the pterodactyl suggest, at least to me, that this is a book which JRRT had read. Here it is for you to read as well: https://gutenberg.org/cache/epub/139/pg139-images.html

And, for further evidence, perhaps this, from Chapter IX?

“Well, suddenly out of the darkness, out of the night, there swooped something with a swish like an aeroplane. The whole group of us were covered for an instant by a canopy of leathery wings, and I had a momentary vision of a long, snake-like neck, a fierce, red, greedy eye, and a great snapping beak, filled, to my amazement, with little, gleaming teeth. The next instant it was gone—and so was our dinner. A huge black shadow, twenty feet across, skimmed up into the air; for an instant the monster wings blotted out the stars, and then it vanished over the brow of the cliff above us.”

This beast derived, perhaps, from Conan Doyle, and/or from what Tolkien called the “new and fascinating semi-scientific mythology of the ‘Prehistoric’”, made me think about another of Tolkien’s creatures, which some have fancifully believed may have come from memories of dinosaurs,

something which had engaged his imagination from far childhood: dragons.

In his essay “On Fairy-Stories” he depicts this as a kind of early passion:

“I desired dragons with a profound desire. Of course, I in my timid body did not wish to have them in the neighborhood, intruding into my relatively safe world, in which it was, for instance, possible to read stories in peace of mind, free from fear. But the world that contained even the imagination of Fafnir was richer and more beautiful, at whatever cost of peril.” (“On Fairy-Stories” in The Monsters and the Critics, 1983, edited by Christopher Tolkien, 135).

Tolkien freely admitted, and more than once, the strong influence of Beowulf on his work and nowhere is this influence stronger, I would say, than in The Hobbit. And yet dragons in Beowulf are surprisingly disposable. The dragon which brings about Beowulf’s dramatic death is dumped over a cliff into the sea:

dracan éc scufun

wyrm ofer weallclif· léton wég niman,

flód fæðmian frætwa hyrde.

“The dragon, too, [that] wyrm they pushed over [the] cliff wall. They let [the] waves take away,

To grasp, [the] keeper of [the] treasure.” (Beowulf, 3132-33)

(My translation, with help from this excellent site: https://heorot.dk/beowulf-rede-text.html I’ve kept “wyrm” mostly because it works nicely with those other double-u words, wall, waves, away. )

And, earlier in the poem, we are told that the dragon which Sigemund kills “hát gemealt”—“has melted”, presumably from its own heat. (Beowulf, 897)

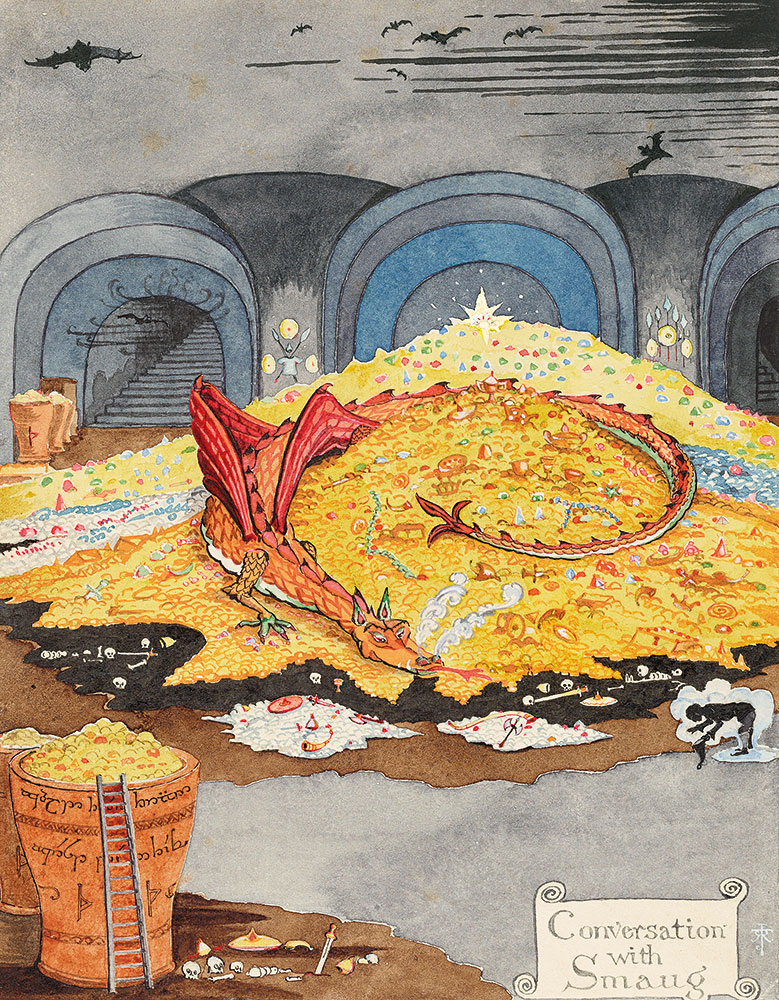

Smaug, however, is different.

(JRRT)

Not only does he talk, which Beowulf’s dragon does not, but, killed by Bard’s black arrow, he becomes a potential paleontological discovery:

“He would never again return to his golden bed, but was stretched cold as stone, twisted upon the floor of the shallows. There for ages his huge bones could be seen in calm weather amid the ruined piles of the old town.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 14, “Fire and Water”)

If Darwin had been puzzled about giant ground sloth remains, what might he have felt if he had discovered Smaug?

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

As the proverb says, “Never laugh at live dragons”,

And remember that, as ever, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

Flanders and Swann, whom I have mentioned before, have a quietly cheerful song about a sloth here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=blDNO5qznjM