Tags

Dickon Among the Indians, Fantasy, Ghan-buri-Ghan, James Fenimore Cooper, Native Americans, On Fairy-Stories, Orcs, Sam Gamgee, The Last of the Mohicans, The Lord of the Rings, Thte Last of the Mohicans, Tolkien, William Morris, Wose

Welcome, as always, dear readers.

I’ve borrowed the title of this posting from a 1938 book by M.R. Harrington, Dickon Among the Lenape Indians (shortened for a reprint to Dickon Among the Indians),

a very interesting attempt to recreate the lives of Algonkian-speaking Native Americans in New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania at the beginning of colonization. (Harrington was fortunate in having local Native Americans to help him in his research. For more on Harrington, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Raymond_Harrington , himself a very interesting man. Please note, by the way, that, although I will use “Indians” occasionally in this piece, when appropriate, I commonly employ the now-standard “Native Americans”.)

The subject of early Native Americans is worth many postings in itself, but where does JRRT fit in?

Well, when you visualize Tolkien, what do you think of?

The schoolboy?

The 2nd lieutenant?

The serious professor?

The man who loved trees?

Suppose, however, instead of military caps

or the shapeless thing we see on his head in later pictures,

we provide him with something as splendid as this—

(A recreation of a Lakota war headdress)

As a man obsessed (a radical term, perhaps, but really accurate, I would say) with language and languages, Tolkien had set himself a problem, when it came to his approach to The Lord of the Rings. It was meant to be a translation, and he himself the editor/translator. Although he would mix in bits of several languages he had invented, the main body of the text would be in English—but English would, in fact, substitute for what he called the “Common Speech”. And yet, because of his passion for language, he wouldn’t allow for complete uniformity of speech, especially as not everyone in his Middle-earth spoke the Common Speech as their first language. One possibility would be to approximate the Common Speech with marks for different accents—the speech of the Rohirrim, for instance, as speakers of what was actually a Germanic language (Old English), might be depicted with the effects of English-speaking Germanic speakers in Tolkien’s day. There was definitely a danger in this, of course—the effect is easily overdone and Tolkien would have been well aware of things like what was—and is—called “stage Irish” with lots of “sure an begorras! and “top of the mornin’s”, caricaturing, in fact, Anglo-Irish. As far as I know, JRRT never considered this approach (although we notice that Sam speaks in a different dialect from Frodo—imitated in the Jackson films by having him speak what in the UK is called “Mummershire”, based upon the distinctive sound of West Country English). Were there other possible models? And, if so, what might be useful? Consider the Orcs, for instance. As Pippin notices, to his surprise, he can understand the Orcs who have captured him and Merry because the first who speaks to him speaks “in the Common Speech, which he made almost as hideous as his own language.” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 3, “The Uruk-hai”) The Orcs, then, although they use the Common Speech with outsiders, have their own distinctive language (actually languages, but use the Common Speech as their lingua franca—for more, see The Lord of the Rings, Appendix F, “Of Other Races”).

What, then, might Tolkien employ as a model for an Orc leader giving a speech, one which would be in the Common Speech, but yet distinctively Orcish—and yet not “stage Orchish”?

And here is where I suggest that Tolkien turned to his childhood reading and his interest in Native Americans—at least those he found in books.

If we go by something which he himself once remarked, perhaps this isn’t so far-fetched a theory as it might appear at first:

“I had very little desire to look for buried treasure or fight pirates, and Treasure Island left me cool. Red Indians were better: there were bows and arrows (I had and have wholly unsatisfied desire to shoot well with a bow), and strange languages, and glimpses of an archaic mode of life, and, above all, forests in such stories.” (On Fairy-Stories in The Monsters and the Critics, 134 For those who might like to see if they remain cool to Treasure Island, see https://archive.org/details/treasureisland00stev/mode/2up with its beautiful illustrations by N.C. Wyeth—and, if you do open it, be sure to read the epigraph: “To the Hesitating Purchaser” as a kind of response to JRRT, although Tolkien would have been a toddler when Stevenson died in 1894.)

We know that William Morris (1834-1896)

was a strong influence on Tolkien’s writing, inspiring medieval elements in JRRT’s work, but there may have been another influence we can detect, which provided a model, using Tolkien’s “strange languages, and glimpses of an archaic mode of life” as a clue—at least for speech: the work of James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851), a once-famous author of historical fiction about the 18th-century US, and, probably, the first author to present Native Americans to Tolkien.

So, how does an Orc leader speak?—sometimes collectively in a highly rhetorical fashion :

“We are the fighting Uruk-hai! We slew the great warrior. We took the prisoners. We are the servants of Saruman the Wise, the White Hand: the Hand that gives us man’s-flesh to eat. We came out of Isengard and led you here, and we shall lead you back by the way we choose. I am Ugluk. I have spoken.” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 3, “The Uruk-hai”)

Compare it, then, with this:

“We came from the place where the sun is hid at night, over

great plains where the buffaloes live, until we reached the big

river. There we fought the Alligewi, till the ground was red with

their blood. From the banks of the big river to the shores of the

salt lake, there was none to meet us. The Maquas followed at a

distance. We said the country should be ours from the place

where the water runs up no longer on this stream, to a river

twenty suns’ journey toward the summer. The land we had

taken like warriors, we kept like men. We drove the Maquas

into the woods with the bears. They only tasted salt at

the licks; they drew no fish from the great lake; we threw them

the bones.”

This is Chingachgook, a Mohican (the last, in fact), speaking to another major character, Natty Bumpo, in James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, 1826 (Chapter III—you can read the novel—again illustrated by N.C. Wyeth—here: https://dn720005.ca.archive.org/0/items/lastofmohicansna00coop/lastofmohicansna00coop.pdf I should add a small warning: Cooper is a man of his time and therefore racism slips in here and there. As well, he is not the world’s best prose stylist, but he was once a best-selling author and the first famous US novelist, so worth your time—and his basic story is still, as far as I’m concerned, a good one. For comic criticism of him, however, see Mark Twain’s “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offences”,1895, here: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/3172/3172-h/3172-h.htm ).

And such a manner of speaking might be adapted to other “strange languages, and glimpses of an archaic mode of life”–

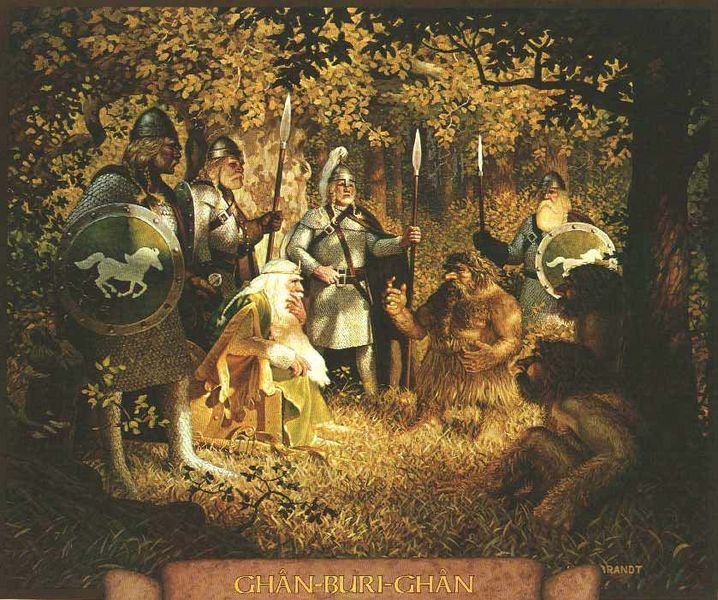

“ ‘Let Ghan-buri-Ghan finish!…More than one road he knows. He will lead you by road where no pits are, no gorgun walk, only Wild Men and beasts. Many paths were made when Stonehouse-folk were stronger. They carved hills as hunters carve beast-flesh. Wild Men think they ate stone for food. They went through Druadan to Rimmon with great wains. They go no longer. Road is forgotten, but not by Wild Men. Over hill and behind hill it lies still under grass and tree, there behind Rimmon and down to Din, and back at the end to Horse-men’s road. Wild Men will show you that road. Then you will kill gorgun and drive away bad dark with bright iron, and Wild Men can go back to sleep in the wild woods.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 5, “The Ride of the Rohirrim”)

(the Hildebrandts)

This is, in fact, the chief of the Woses, an early people of Middle-earth now confined to a forest area not far from Minas Tirith. His home language (of which JRRT tells us very little) is clearly not the Common Speech and so his address to Theoden and his lieutenants follows that of Ugluk and, in fact, of Chingachgook, suggesting, once more by the use of the model provided long before by James Fenimore Cooper, that Tolkien has earned his own place “among the Indians”.

As ever, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

If someone from many centuries before the time of The Lord of the Rings, the chief Nazgul, speaks in what is meant to be an archaic dialect, what would Sauron, older yet, sound like?

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O