Welcome, dear readers, as always.

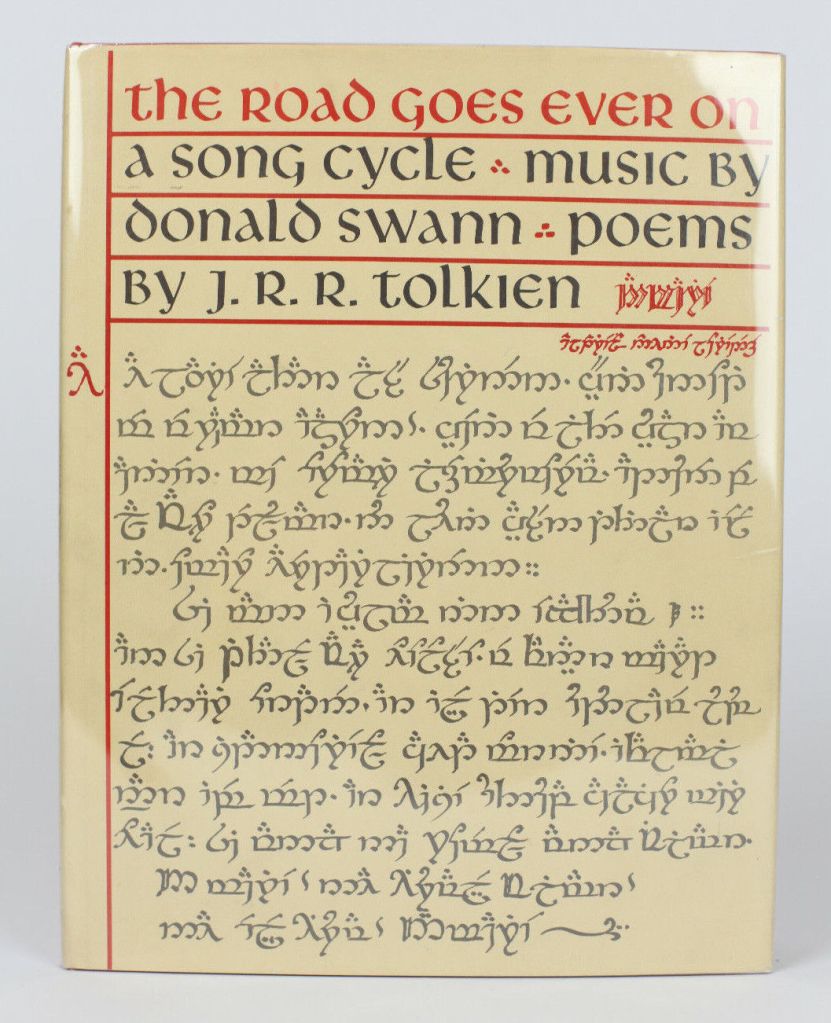

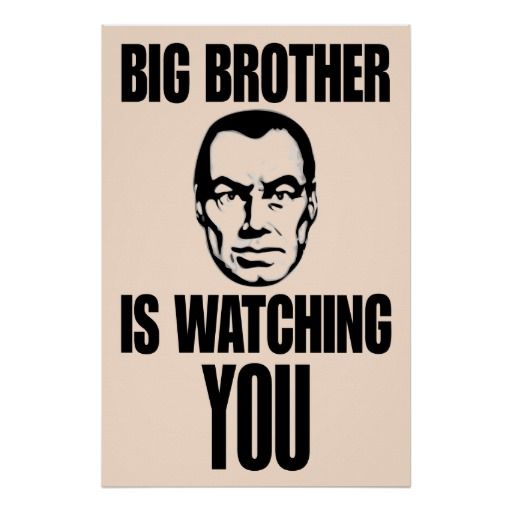

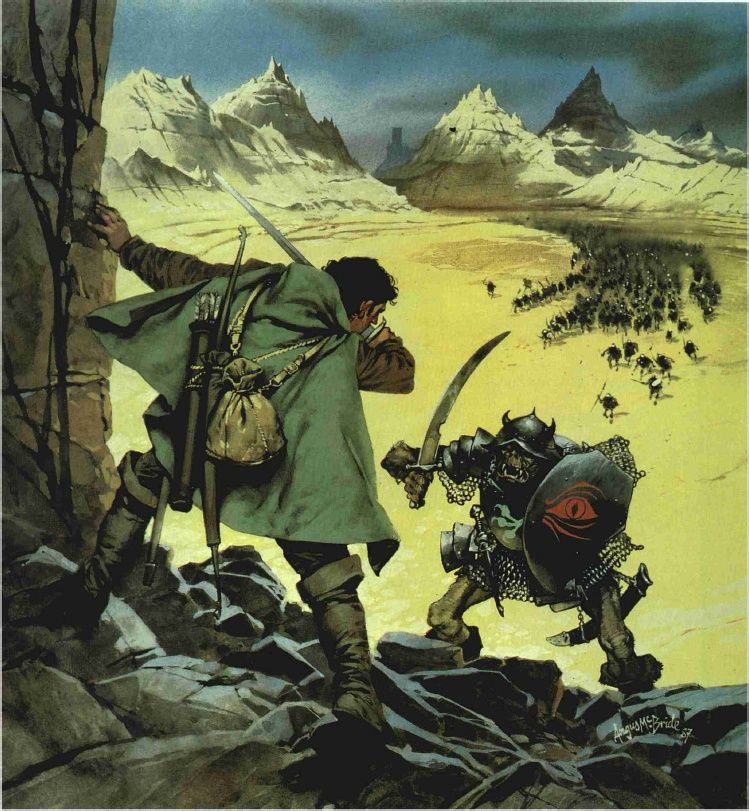

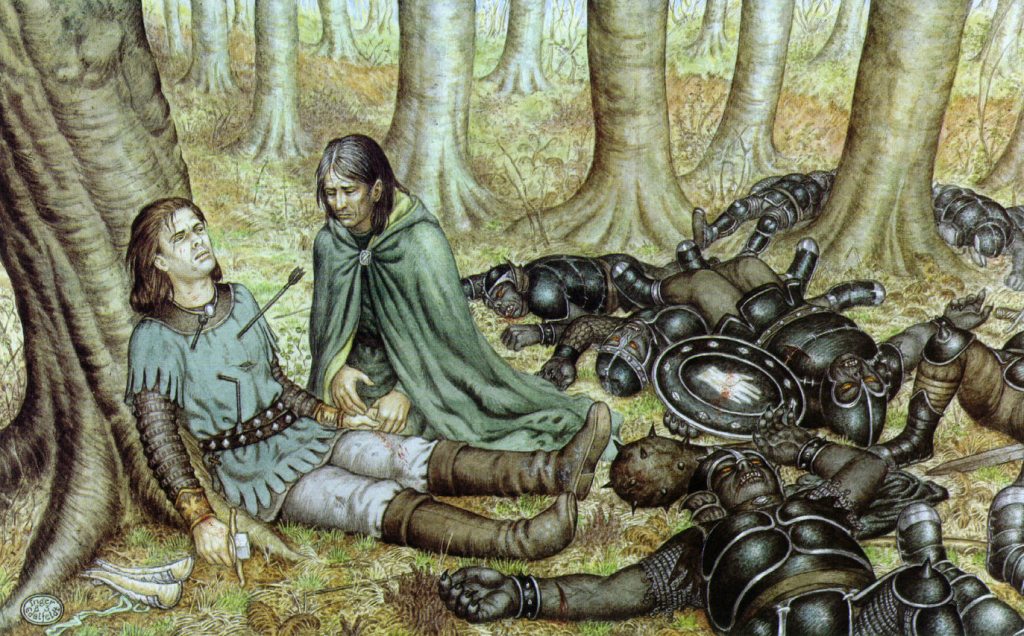

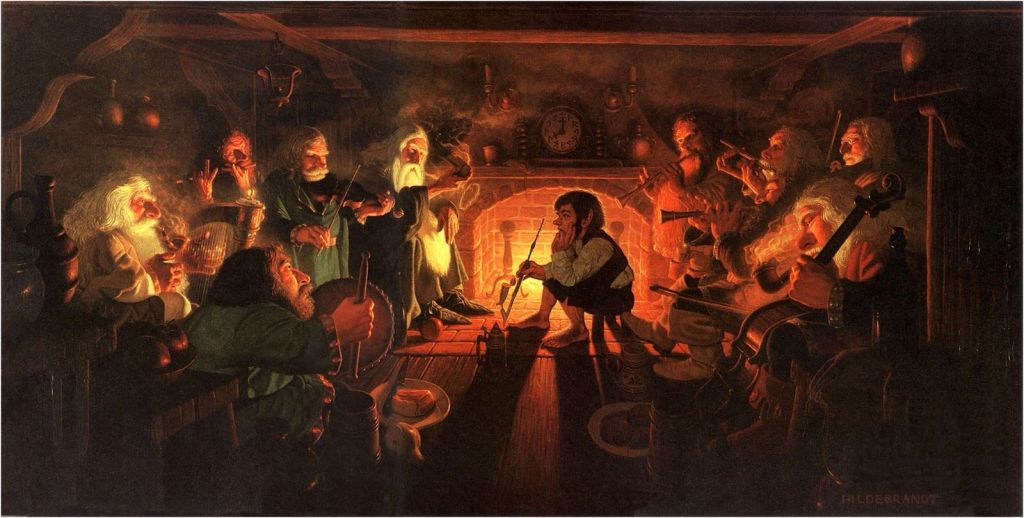

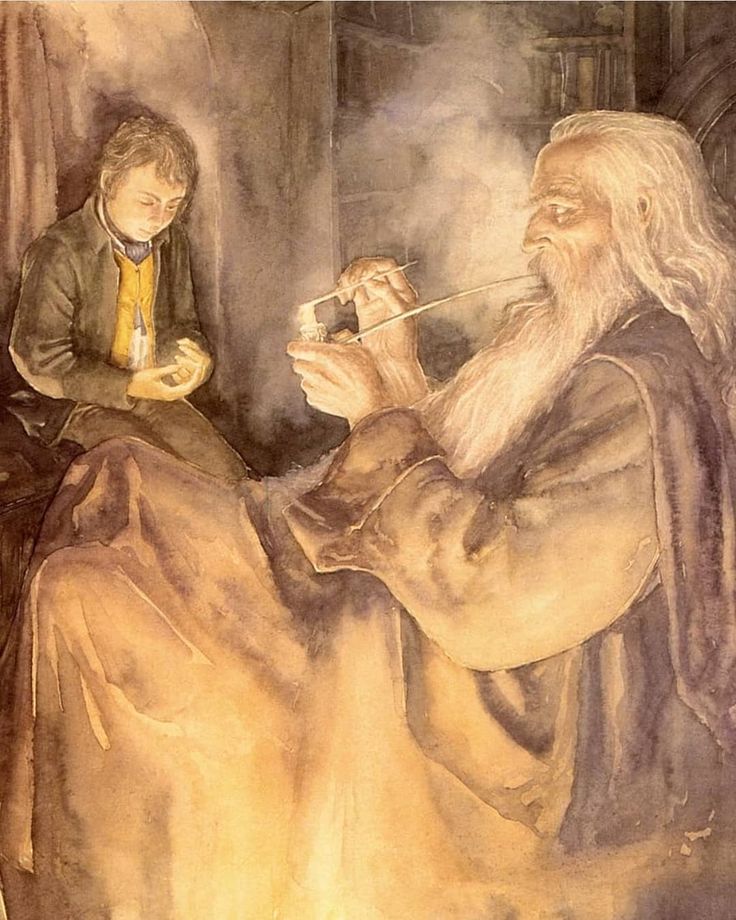

“ ‘I am sorry,’ said Frodo. ‘But I am frightened and I do not feel any pity for Gollum.’

‘You have not seen him,’ Gandalf broke in.

‘No, and I don’t want to,’ said Frodo. ‘I can’t understand you. Do you mean to say that you, and the Elves, have let him live on after all those horrible deeds? Now at any rate he is as bad as an Orc, and just an enemy. He deserves death.’

‘Deserves it! I daresay he does. Many that live deserve death. And some that die deserve life. Can you give it to them? Then do not be too eager to deal out death in judgement.’” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter Two, “The Shadow of the Past”)

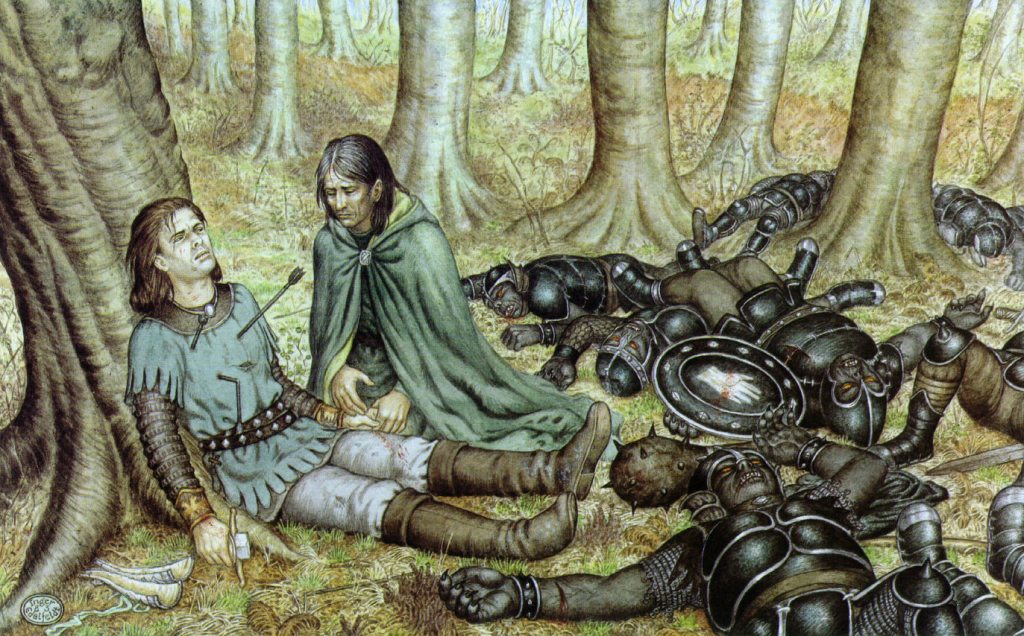

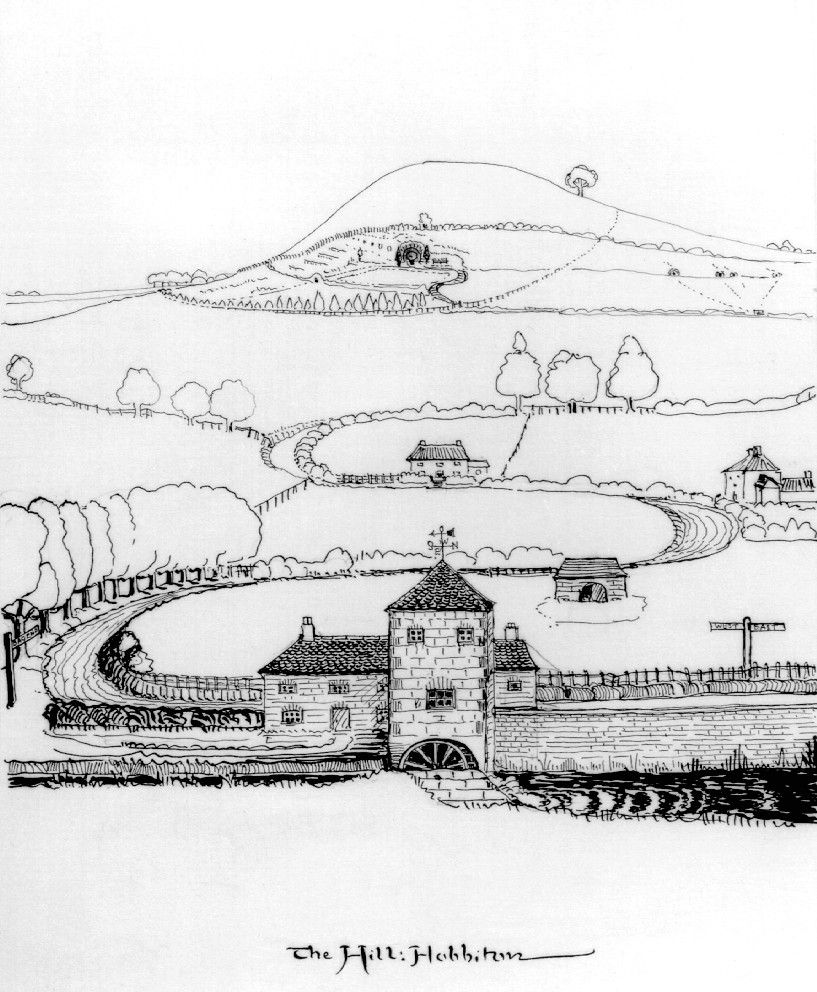

(Alan Lee)

I’ve always thought that this was one of the most striking passages early in The Lord of the Rings. Gandalf has been telling Frodo about his meeting with Gollum, including the unwelcome thought that Sauron, who has found out from Gollum that the Ring wasn’t lost and, in fact, was in the hands of someone called “Baggins” and may even be aware that “Baggins” and “Shire” are linked. Frodo’s natural reaction is to panic and to blame Gollum, turning vindictive in his fear. In contrast, Gandalf, whose more humane reaction was probably a product of his Maia nature and his long experience of events and people in Middle-earth (having arrived there in TA 1000, 2000 years before the joint birthday party which sets The Lord of the Rings in motion—TA 3001—see Christopher Tolkien, Unfinished Tales, 405, “The Istari”), opposes Frodo’s sentence of death with one of compassion, so, when Frodo says, “What a pity that Bilbo did not stab that vile creature when he had a chance!” Gandalf replies, “Pity? It was Pity that stayed his hand. Pity, and Mercy: not to strike without need.”

I’ve also wondered where such a humane sentiment came from in Gandalf’s creator. His deep Christian faith must have played a part, but I think another element was his experience in 1916,

when, as he writes to his son, Michael:

“Bolted into the army: July 1915. I found the situation intolerable and married on March 22, 1916. May found me crossing the Channel…for the carnage of the Somme.” (from a letter to Michael Tolkien, 6-8 March, 1941, Letters, 73)

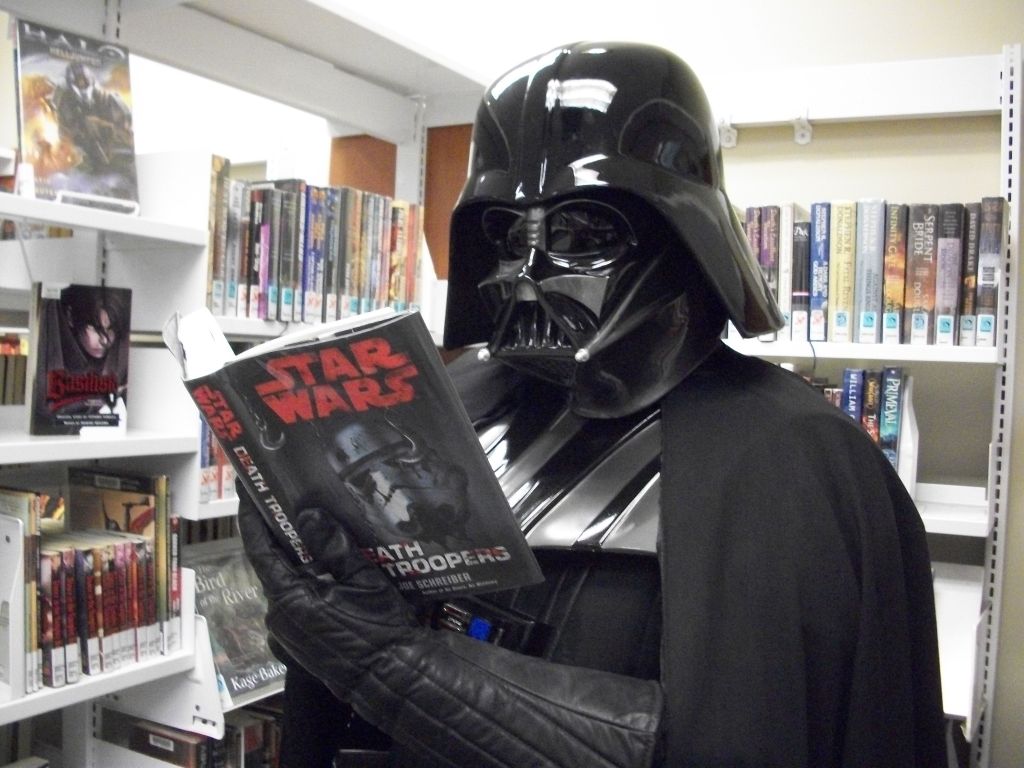

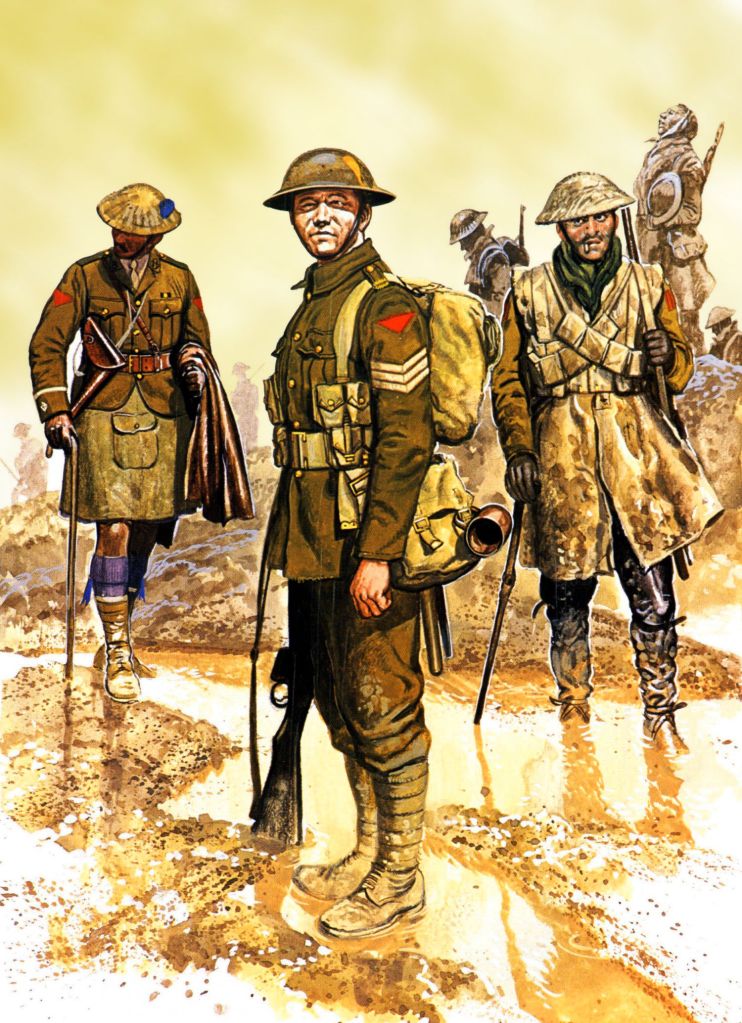

This was the beginning of Tolkien’s short experience of actual combat in what was called, at the time, The Great War—meaning “the Big War” in British English, as it was the biggest war in any contemporary’s experience and, without World War II, it obviously couldn’t be called “World War I”. At the same time, I think that JRRT’s time at the front, although really only measured in a few months (June to November, 1916—see Carpenter, Tolkien, 90-96 for details) might have made him find that other meaning of “great” ironic and I suspect that he would have agreed with Yoda’s reply to Luke’s “I’m looking for a great warrior.”—“Ahhh! A great warrior…Wars not make one great.” in Star Wars V . (You can read the script for this scene, pages 55-58, at: https://assets.scriptslug.com/live/pdf/scripts/star-wars-episode-v-the-empire-strikes-back-1980.pdf )

The new second lieutenant

belonged to one of the battalions (sub-units) of the Lancashire Fusiliers,

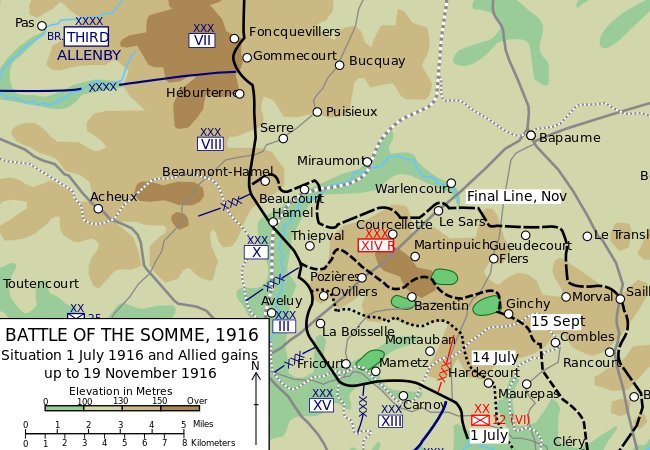

one of the oldest infantry regiments in the British Army (begun as “Peyton’s Regiment” in 1688—you can read more about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lancashire_Fusiliers ). It was only one of the many units designated to be part of what would become known as “The Somme”, a battle which lasted from 1 July to 18 November, 1916—and which would cost the British alone 57,470 casualties on the first day and a total of 415,690 by 18 November. (You can read a very detailed article about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Somme )

The battlefield was huge—

and Tolkien would have seen only a tiny portion of it, but what he saw should have terrified any sensible person.

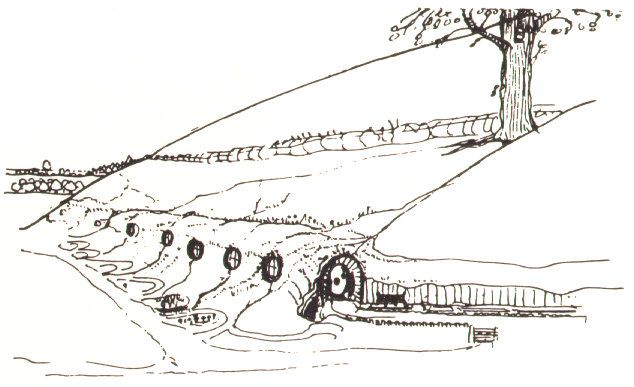

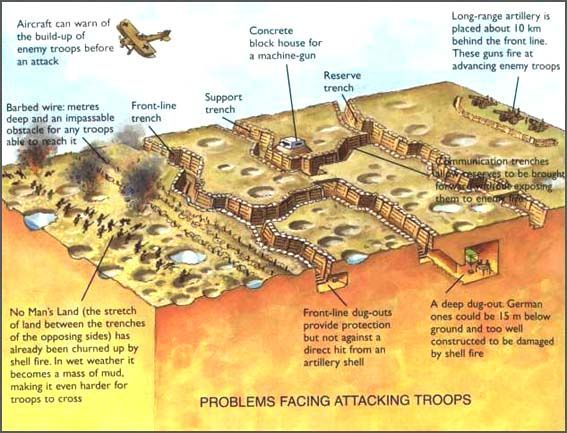

We begin with the trench he would have crouched in, waiting for the order to attack (going “over the top”, which means climbing up over the forward lip of the trench).

In front of the trench was a long stretch of barbed wire, which had to be negotiated before any further forward motion was to be made.

Ahead lay the wilderness called “no man’s land”.

This varied, depending upon what had been there before the War, but, since it was often pounded by one side or the other’s artillery, whatever had been there before—farms, villages, forests—had been turned into a beaten-down desert of ruins.

Beyond there, lay the enemy’s wire entanglements.

And, beyond there were the enemy’s trenches—as many as three lines of them.

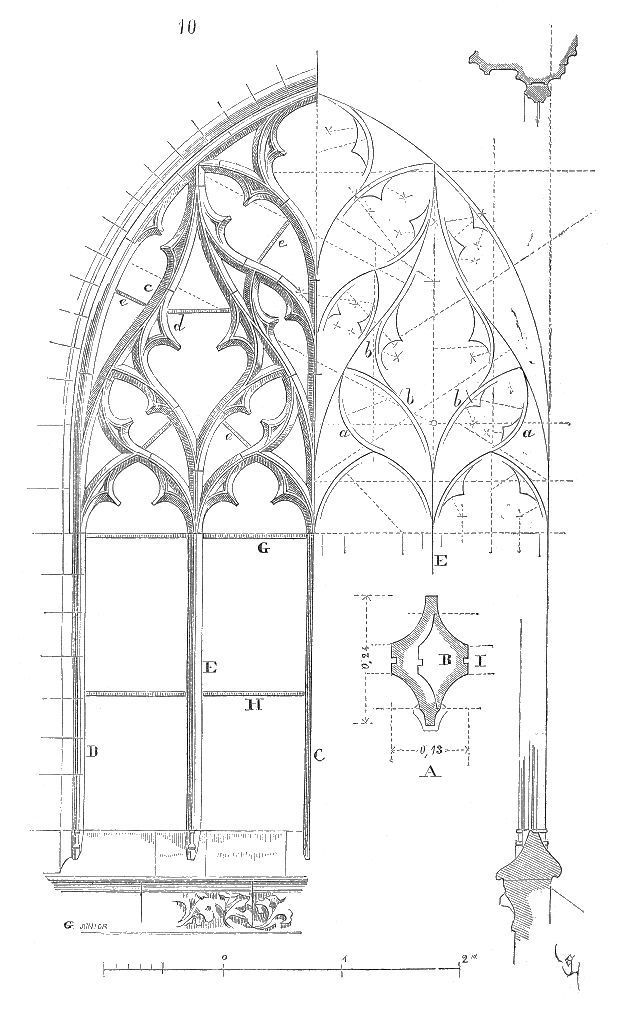

These could look like the trench Tolkien had crawled out of, but they could also be much more elaborate, with pillboxes made of concrete, reinforced with steel girders, and buried under a layer of soil both to conceal them and to help to protect them from the shells which the enemy would attempt to drop on them.

(This is the rear entry of a German pillbox.)

In those trenches would be multiple machine guns, placed to sweep the wire which lay before them.

Each of these guns could fire 600 rounds per minute, to which would be added the rifle fire of the infantry who were the trenches’ garrison.

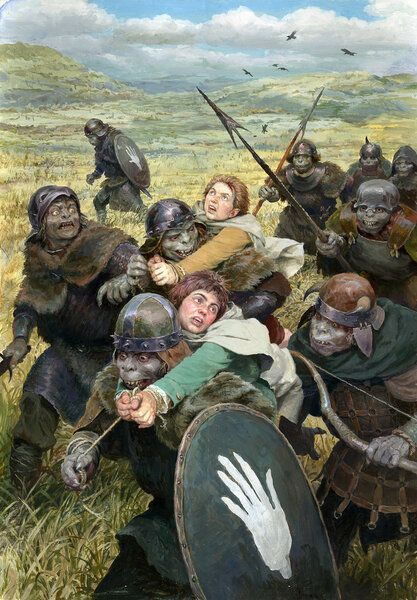

(Peter Dennis)

Behind the trenches would be artillery, whose job was, when an attack began, to fire as many shells as possible into the enemy trenches and into no man’s land, to slow down, if not stop, the enemy attack, forcing the attackers back with heavy casualties.

Before the attack on 1 July, the British had used their heavy artillery

to destroy enemy entrenchments and, hopefully, to cut apart those deep fields of barbed wire in front of them.

Unfortunately, on 1 July, the artillery—even after a massive bombardment—failed to disrupt the wire and soldiers were simply pinned to it, perfect targets for machine gunners and the casualties mounted—and mounted

so that one can easily see why Tolkien would refer to his experience in 1916 as “the carnage of the Somme” with its British 57,470 casualties on its first day and 415,690 by its final one.

In later years, he might have a somewhat ambivalent view of what he had gone through, writing to his son Michael that

“War is a grim hard ugly business. But it is as good a master as Oxford, or better.” (letter to Michael Tolkien, 12 July, 1940, Letters, 61)

and yet could also write this about the end of the second war:

“The appalling destruction and misery of this war mount hourly, destruction of what should be (indeed is) the common wealth of Europe, and the world, if mankind were not so besotted, wealth the loss of which will affect us all, victors or not. Yet people gloat to hear of the endless lines, 40 miles long, of miserable refugees, women and children pouring West, dying on the way. There seem no bowels of mercy or compassion, no imagination, left in this dark diabolic hour.” (letter to Christopher Tolkien, 20 January, 1945, Letters, 160)

Having experienced one of the bloodiest periods in the Great War, it is no wonder, then, that JRRT could sound like Gandalf, speaking of mercy, on the one hand, and, on the other, like a changed Frodo near the end of his adventures:

“ ‘Fight?’ said Frodo. ‘Well, I suppose it may come to that. But remember: there is to be no slaying of hobbits, not even if they have gone over to the other side. Really gone over, I mean; not just obeying ruffians’ orders because they are frightened. No hobbit has ever killed another on purpose in the Shire, and it is not to begin now. And nobody is to be killed at all, if it can be helped. Keep your tempers and hold your hands to the last possible moment.’ “ (The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 8, “The Scouring of the Shire”)

As always, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

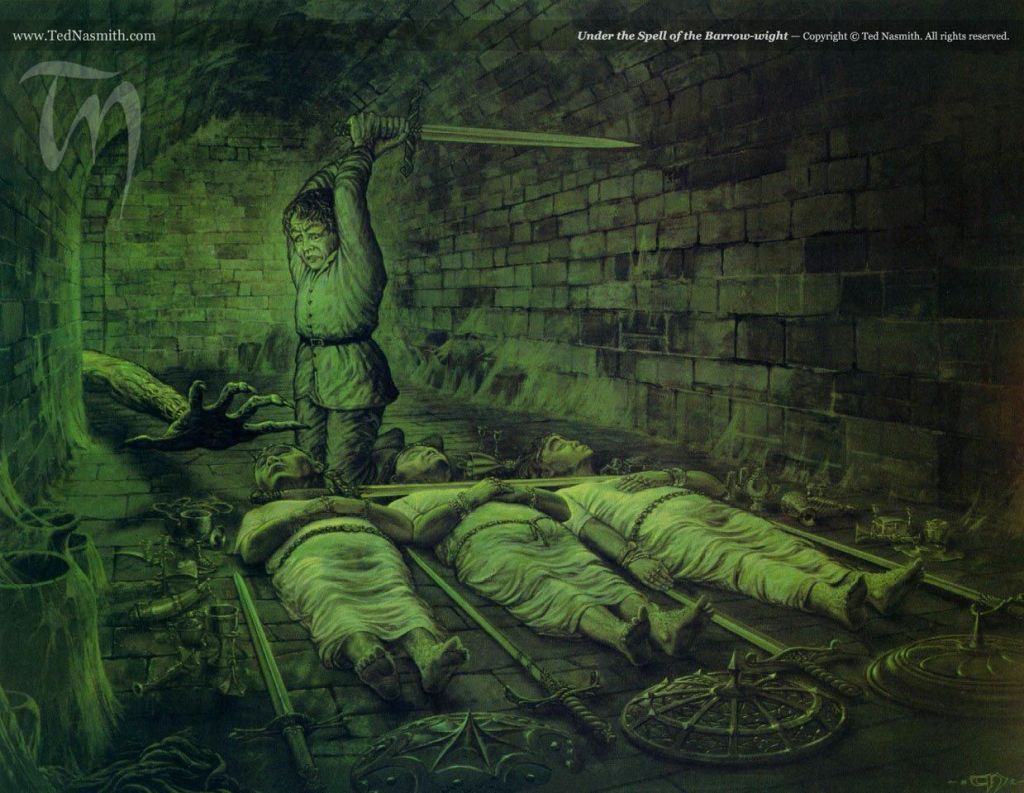

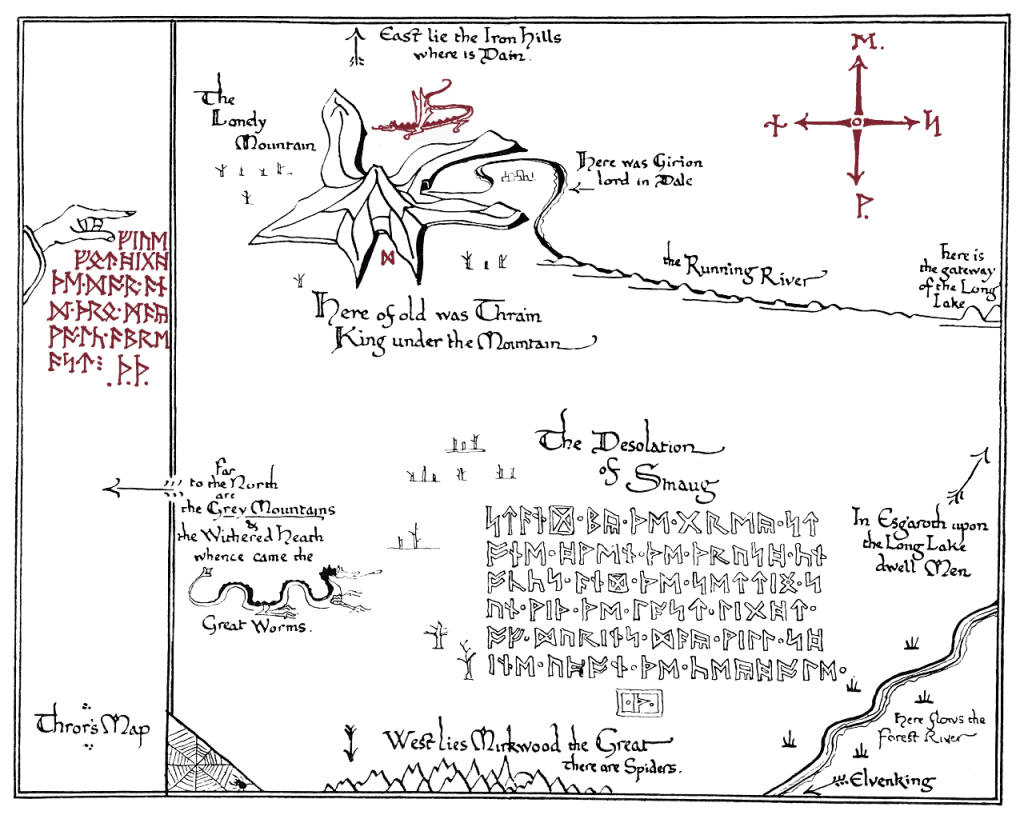

Consider what, had Bilbo done what Frodo wished, might have been Frodo’s fate—and Middle-earth’s,

(Ted Nasmith)

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O