Tags

Brutus, cassius, ears, Fantasy, Gandalf, Hamlet, henbane, Julius Caesar, lotr, Marcus Antonius, Orthanc, Palantir, poison, Saruman, Sauron, Shakespeare, Tolkien

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

In the closing of the second part of this little series, I quoted Marcus Antonius in his funeral oration upon Julius Caesar in Shakespeare’s play of the same name.

It is a masterpiece, both in its design and in its deception: saying one thing for the assassins, led by Brutus, to hear, and, on the other, poisoning the common people against the assassins, originally seen as liberators of the Republic. You probably remember its opening:

“Friends, Romans, Countrymen, lend me your ears:

I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him:

The euill that men do, liues after them,

The good is oft enterred with their bones,

So let it be with Caesar. The Noble Brutus,

Hath told you Caesar was Ambitious:

If it were so, it was a greeuous Fault,

And greeuously hath Caesar answer’d it.

Heere, vnder leaue of Brutus, and the rest

(For Brutus is an Honourable man,

So are they all; all Honourable men)

Come I to speake in Caesars Funerall.”

(Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene 2, from the First Folio, 1623, in the original spelling. You can see it at my favorite site for the plays: https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/JC_F1/scene/3.2/index.html )

Speech with a deceptive goal is a theme of this series, as, in the first part, were poison–and ears.

In the scene in Shakespeare’s play, Marcus Antonius plays a dangerous game. In order to be able to speak, he has made a deal with the assassins of Caesar not to say anything inflammatory against them, and so we see those words “Honourable men” repeated, as if Antonius is going to praise them—while only burying Caesar, as he says—just the sort of thing which we can imagine the assassins wanted to hear. And yet, as he continues, “Honourable men” gradually becomes ironic and, by the end of his speech, he controls the mob and it’s clear that the assassins are no longer considered liberators, but murderers, Antonius having successfully poisoned those lent ears against the very men who foolishly gave him leave to speak.

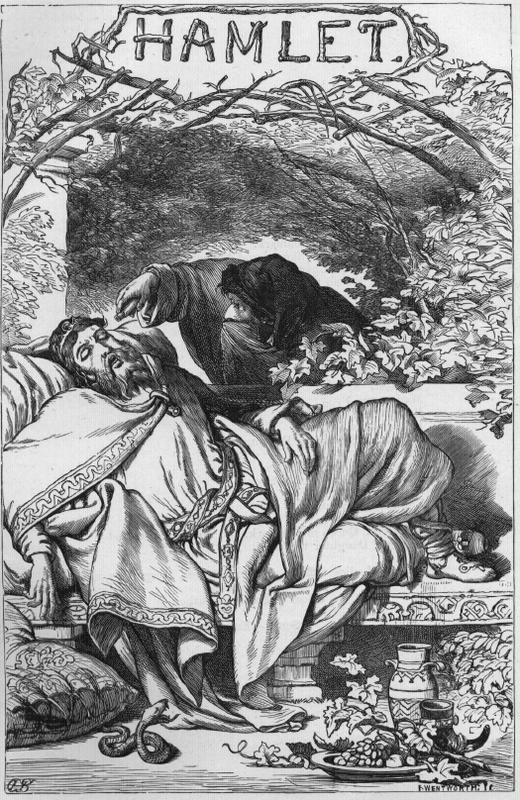

We began the series with poison—and Shakespeare: literal poison (possibly henbane)

which, as Hamlet’s ghostly father tells Hamlet, had been administered to him through his ear by his own brother, Claudius, while he was napping in his garden

But, as we progressed, we moved from that chemical murder to a different kind of destruction, spiritual, in the case of Saruman in the second installment, and now, in the third and final installment, we move to the instrument of that poisoning, include a second poisoning victim, and find the mind behind it all and that mind’s method of persuasion, which, I would suggest, must be very like Antonius’ initial remarks, seeming to praise the assassins, but, just like his, with another motive underneath.

(JRRT)

When Saruman, failing to succeed with Theoden, has turned to Gandalf, Gandalf has alluded to his previous visit with Saruman, saying:

“What have you to say that you did not say at our last meeting?…Or, perhaps, you have things to unsay?” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 10, “The Voice of Saruman”)

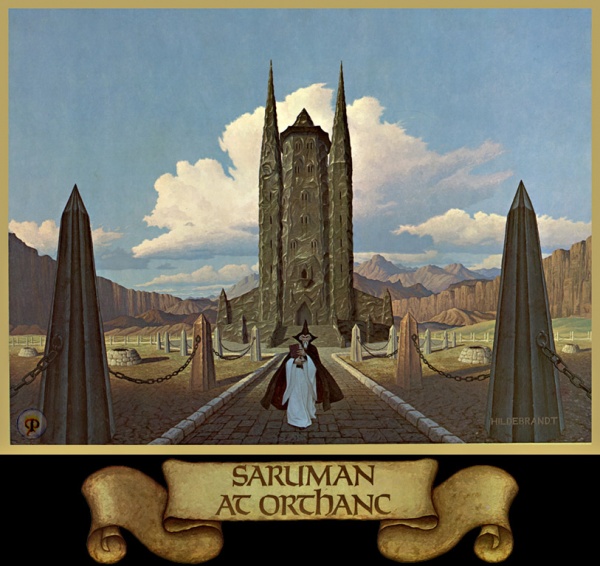

That last meeting had ended with Gandalf’s imprisonment in the tower of Orthanc,

(the Hildebrandts)

but, before that, Saruman had tried to persuade Gandalf to become an ally, and not only of Saruman, but of someone else, his speech including these words:

“We can bide our time, we can keep our thoughts in our hearts, deploring evils done by the way, but approving the high and ultimate purpose: Knowledge, Rule, Order; all the things we have so far striven in vain to accomplish…” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 2, “The Council of Elrond”)

Gandalf’s reply then suggests that what Saruman is saying is not really his own argument:

“ ‘I have heard speeches of this kind before, but only in the mouths of emissaries sent from Mordor to deceive the ignorant.’ “

What is it in those words which betrays their original authorship?

In the draft of a letter to Peter Hastings, Tolkien wrote:

“Sauron was of course not ‘evil’ in origin. He was a ‘spirit’ corrupted by the Prime Dark Lord…Morgoth. …at the beginning of the Second Age he was still beautiful to look at, or could still assume a beautiful visible shape—and was not indeed wholly evil, not unless all ‘reformers’ who want to hurry up with ‘reconstruction’ and ‘reorganization’ are wholly evil, even before pride and the lust to exert their will eat them up.” (draft of a letter to Peter Hastings, September, 1954, Letters, 284)

What Gandalf is actually hearing then is the thinking of Sauron and his “high and ultimate purpose”, but wrapped in words which will sound familiar to Saruman and appeal to his increasing arrogance—those words “high and ultimate purpose” echo Saruman’s depiction later in the story of just who the Istari are:

“Are we not both members of a high and ancient order, most excellent in Middle-earth?” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 10, “The Voice of Saruman”)

That “order” was not sent to Middle-earth for “Knowledge, Rule, Order”, however, as this entry in the Appendices to The Lord of the Rings tells us:

“When maybe a thousand years had passed, and the first shadow had fallen on Greenwood the Great, the Istari, or Wizards appeared in Middle-earth. It was afterwards said that they came out of the Far West and were messengers sent to contest the power of Sauron, and to unite all those who had the will to resist him; but they were forbidden to match his power with power, or to seek to dominate Elves or Men by force and fear.” (The Lord of the Rings, Appendix B: “The Third Age”)

Marcus Antonius has spoken indirectly to the assassins and directly to the mob, both through their ears, but Sauron’s words have reached Saruman through this—

(the Hildebrandts)

which we know that Saruman has had as it is flung through the doorway of Orthanc by Grima and almost brains Gandalf—

“With a cry Saruman fell back and crawled away. At that moment a heavy shining thing came hurtling down from above. It glanced off the iron rail, even as Saruman left it, passing close to Gandalf’s head, it smote the stair on which he stood.”

I never think of a palantir without thinking of another device used for conning unsuspecting victims—

Staring into the ball might have a kind of hypnotic effect, but it clearly also has the effect of focusing the will of another upon the victim—as Pippin found out to his grief:

“In a low hesitating voice Pippin began again, and his words grew clearer and stronger. ‘I saw a dark sky, and tall battlements…And tiny stars. It seemed very far away and long ago, yet hard and clear…Then he came. He did not speak so that I could hear words. He just looked and I understood…He said: “Who are you?’ I still did not answer, but it hurt me horribly; and he pressed me, so I said: ‘A hobbit.’ Then suddenly he seemed to see me, and he laughed at me. It was cruel. It was like being stabbed with knives…Then he gloated over me. I felt I was falling to pieces.’ “ (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 11, “The Palantir”)

This isn’t Sauron’s only use of such a device for his poisoning—another palantir lies in Minas Tirith and it’s clear from its possessor, Denethor’s, speech how Sauron has reached him:

“Do I not know thee, Mithrandir? Thy hope is to rule in my stead, to stand behind every throne, north, south, or west. I have read thy mind and its policies…So! With the left hand thou wouldst use me for a little while as a shield against Mordor, and with the right bring up this Ranger of the North to supplant me.”

And here we see how Sauron has distorted the original Istari goals, which Tolkien had described to Naomi Mitchison:

“They were thought to be Emissaries (in the terms of this tale from the Far West beyond the Sea), and their proper function, maintained by Gandalf and perverted by Saruman, was to encourage and bring out the native powers of the Enemies of Sauron.” (letter to Naomi Mitchison, 25 April, 1954, Letters 269-270)

Denethor is correct in understanding that Gandalf—and supposedly all of the Istari—are meant to stand behind thrones—but to encourage their possessors to oppose Sauron, not to gain power for themselves, as Saruman deceived himself into thinking. Denethor has not read Gandalf’s mind, but Sauron has definitely read Denethor’s—when Gandalf asks him what he wants, he replies:

“ ‘I would have things as they were in all the days of my life…and in the days of my longfathers before me: to be the Lord of this City in peace, and leave my chair to a son after me, who would be his own master and no wizard’s pupil.”

The Stewards are not the kings of Gondor. Although they have ruled for centuries, they are merely the lieutenants of the Numenorean kings, holding Gondor until a rightful king should appear, but it’s clear that Denethor has forgotten that, seeming to assume that he is the king—something surely in which Sauron has encouraged him . And we see here another sore point: Faramir.

In the midst of a complex scene in which Faramir reports that he had met Frodo, Denethor turns to him sharply:

“Your bearing is lowly in my presence, yet it is long since you turned from your own way at my counsel. See, you have spoken skillfully, as ever; but I, have I not seen your eyes fixed on Mithrandir, seeking whether you said well or too much? He has long had your heart in his keeping.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 4, “The Siege of Gondor”)

So Sauron has spotted two weak points in Denethor: a mistaken idea about his role in the governing of Gondor and his jealous attitude towards his younger son. This almost leads to Faramir’s death by burning and certainly does his father’s.

(Robert Chronister—about whom I have so far found nothing, although it’s clear that he’s illustrated more than one scene from The Lord of the Rings.)

Marcus Antonius, one of Julius Caesar’s right-hand men, has tricked Caesar’s assassins into letting him speak,

initially using language which they want to hear, but, just below the surface, and increasingly, as he proceeds, his word choice turns the mob listening to those same words into a force which will help to drive the assassins from Rome and, eventually, in the case of two of the main assassins, Brutus,

(This is a very famous coin pattern. On the obverse—the “heads”—we see what we presume is an image of Brutus, with the caption “Brut[us]” and his assertion that he has the state’s authority: “Imp[erator]”, along with the name of the mint master, “L[ucius] Plaet[orius] Cest[ianus]”. On the reverse—the “tails”—we see a shorthand version of the claim of the assassins: “Eid[ibus] Mar[tis]”—“on the ides of March”, plus two Roman “pugiones”—military daggers—bracketing a “liberty cap”—used in the ceremony of freeing a slave—hence: “On the Ides of March, I/we, by the use of these daggers, freed Rome from its slavery (to Caesar)” )

and Cassius,

(Unfortunately, we have no definite image of Cassius—this is a coin minted on his authority by his deputy, Marcus Servilius. The obverse has an image of “Libertas”, along with an abbreviated form of his name, “C[aius] Cassi[us]”, and that claim to have the authority of the state: “Imp[erator]”. The reverse has the name of his lieutenant, “M[arcus] Servilius”, his deputy rank “Leg[atus]” and what’s called an “aplustre”, which is the decorative stern of a Roman warship, thought to commemorate Cassius’ defeat of the navy of Rhodes.)

to defeat and suicide—Marcus Antonius’ ear-poison working very effectively.

For Middle-earth, there is a happier ending. The real goal of sending the Istari succeeds, even with the treachery of Saruman, brought about through the poison introduced and spread by Sauron through the palantiri, which affects Denethor, as well, teaching us that toxicity is just as deadly in word as it is in deed.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

Lend no one your ears unless you’re clear what he/she wants,

And remember that, as ever, there’s

MTCIDC

O