Tags

Barrow-downs, Barrow-wight, Bilbo, Bree, bridge-of-strongbows, Fantasy, Frodo, Great East Road, Nazgul, Shire, The Bridge of Stonebows, The Lord of the Rings, The Prancing Pony, Tolkien, Tom Bombadil, travel

As always, welcome, dear readers.

In “To Bree (Part 1)”, we had followed Bilbo & Co.

(Hildebrandts)

(Hildebrandts)

eastwards,

but only as far as Bree, echoing the remark in The Lord of the Rings:

“It was not yet forgotten that there had been a time when there was much coming and going between the Shire and Bree.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 9, “At the Sign of the Prancing Pony”)

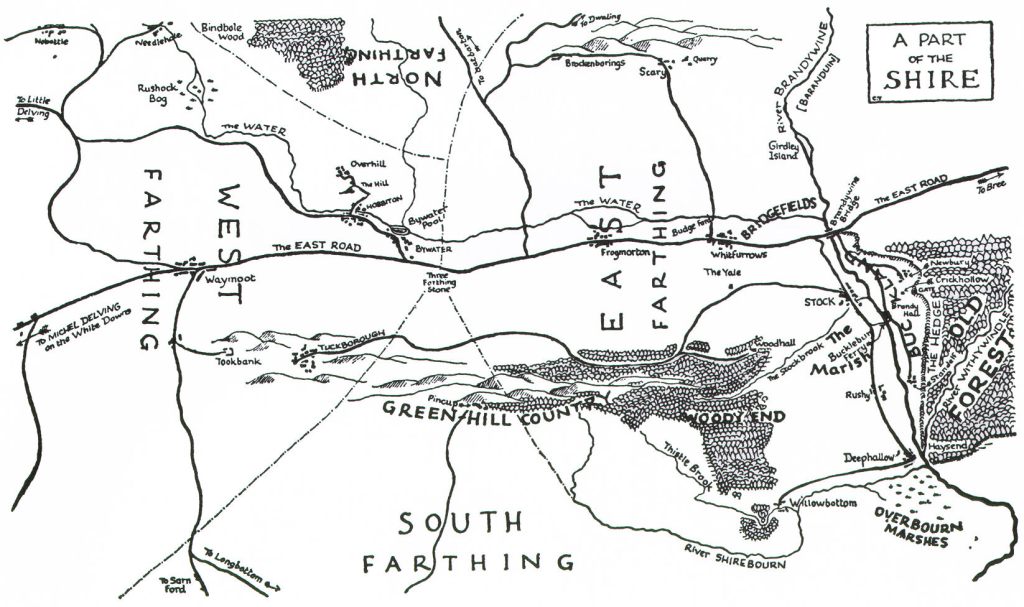

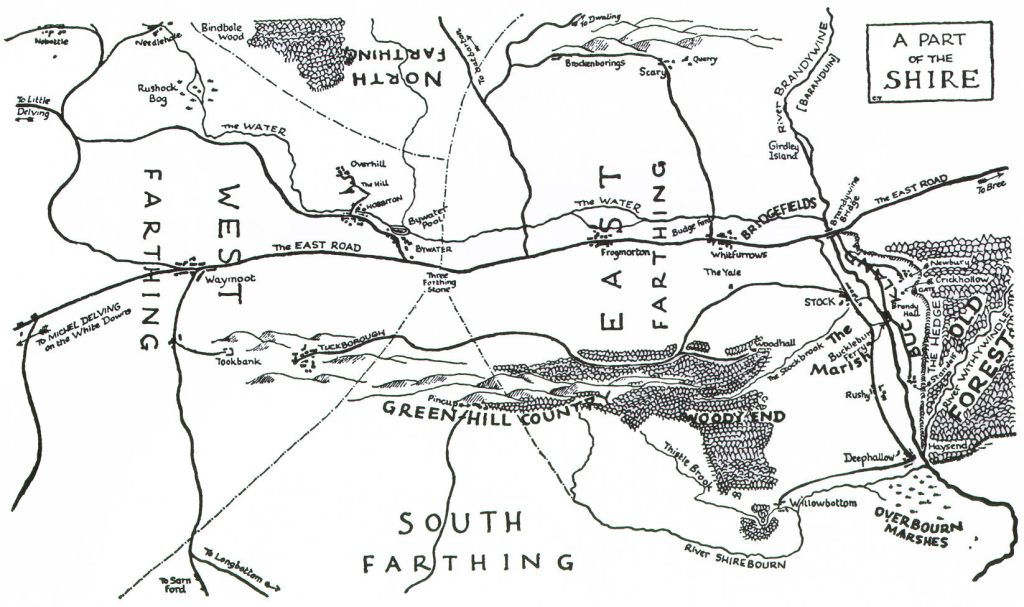

Oddly, however, although I supposed that we were traveling through the East Farthing

(Christopher Tolkien)

through Frogmorton and Whitfurrows,

to the Bridge of Strongbows,

(Stirling Bridge, actually—for more see: https://www.historicenvironment.scot/visit-a-place/places/stirling-old-bridge/ )

the description in The Hobbit was wildly different:

“Then they came to lands where people spoke strangely, and sang songs Bilbo had never heard before. Now they had gone on far into the Lone-lands, where there were no people left, no inns, and the roads grew steadily worse. Not far ahead were dreary hills, rising higher and higher, dark with trees. On some of them were old castles with an evil look, as if they had been built by wicked people.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 2, “Roast Mutton”)

with, eventually, a surprise for us Bree-bound folk: no Bree.

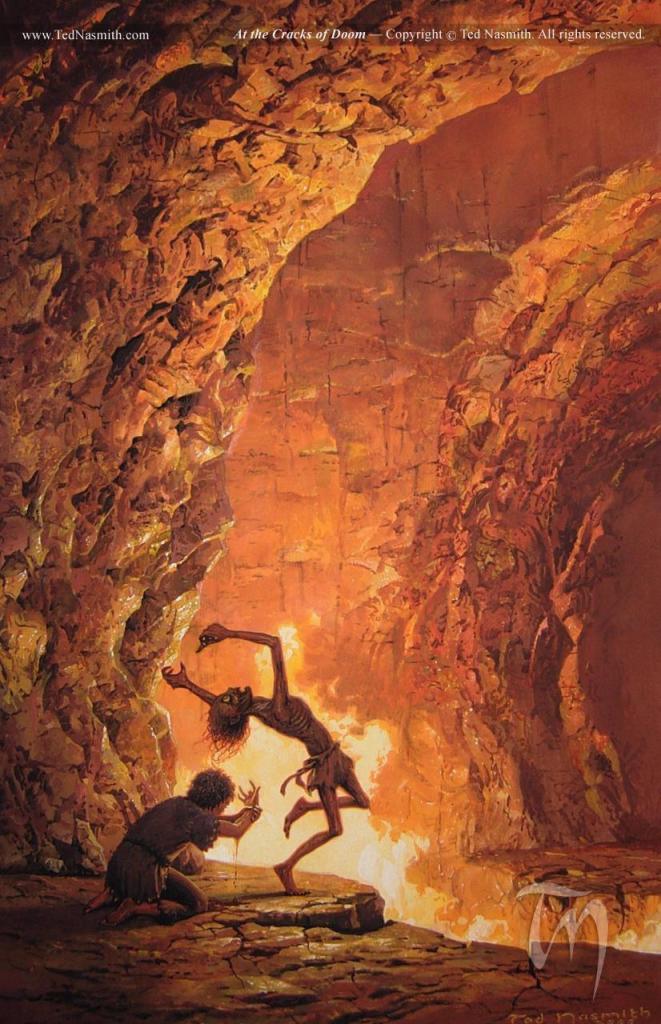

So, back we went to the Green Dragon, in Bywater, where Bilbo started and now we begin again, with Frodo. Times have changed, however, and unlike the innocent Bilbo, we are in a different world, where Mordor isn’t just a distant place name and its servants are looking for Baggins.

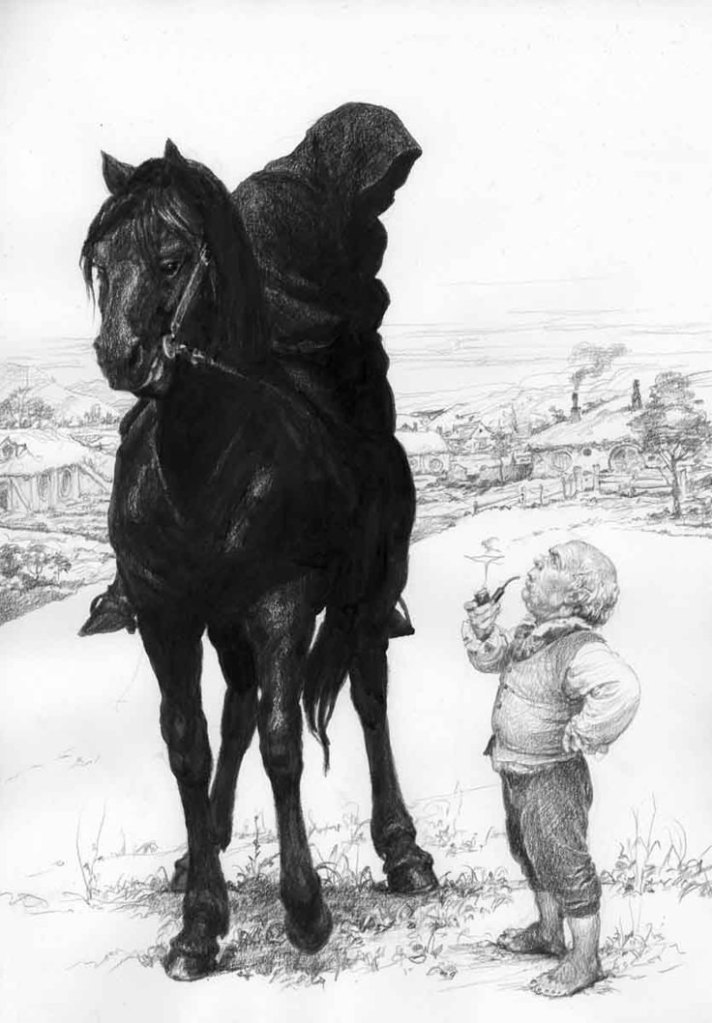

(Denis Gordeev)

Frodo doesn’t take the Great East Road,

(Christopher Tolkien)

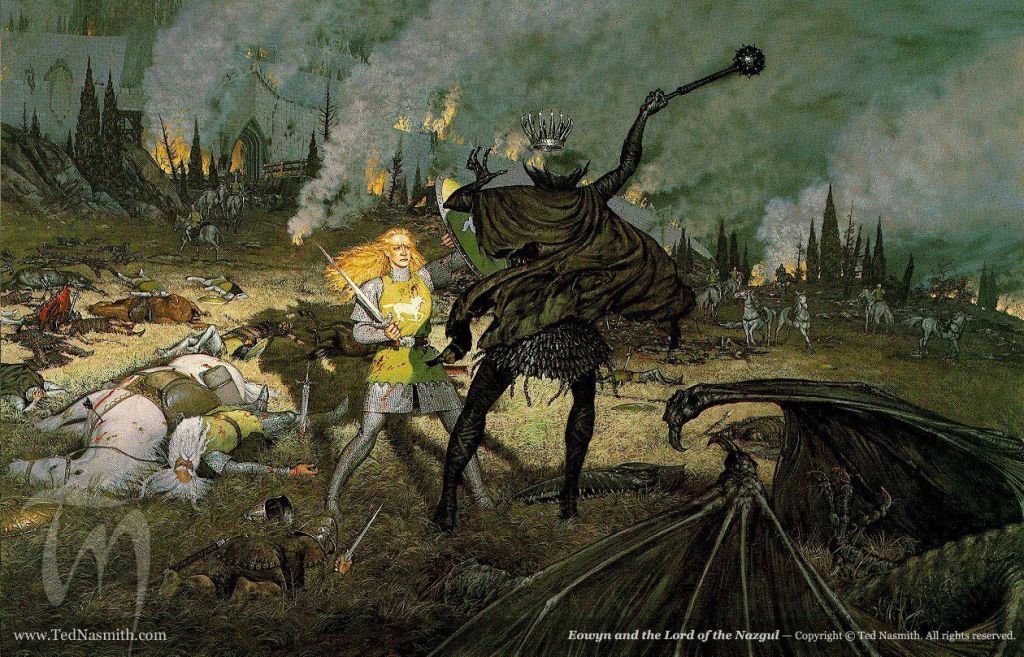

but cuts across country, narrowly avoiding one of the searchers,

(Angus McBride)

taking shelter with a local farmer, and finally reaching the ferry across the Brandywine just ahead of his pursuers.

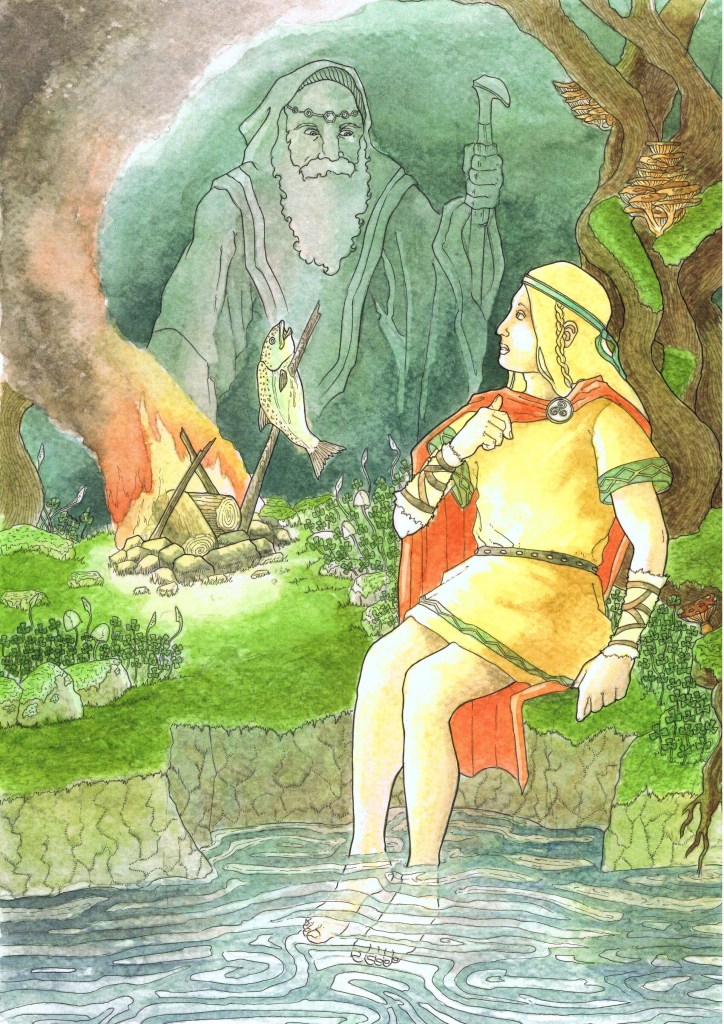

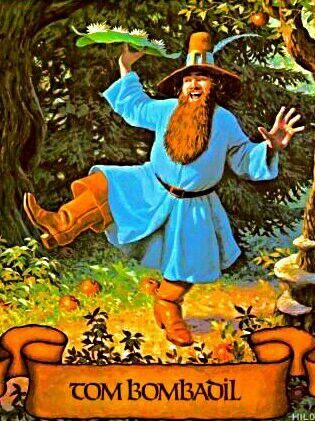

Although this is a very indirect route, Frodo and his companions eventually reach Bree, but even though I would love to meet Tom Bombadil,

(the Hildebrandts)

I prefer a direct route, so we’ll continue on the Great East Road, cross the Bridge of Strongbows, and head eastwards.

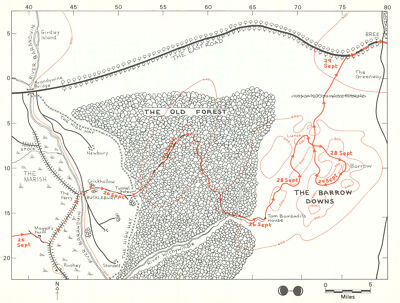

(from Barbara Strachey, The Journeys of Frodo, a much-recommended book, if you don’t have a copy)

So what do we see?

Over the bridge—and here’s another possibility for it, the Clopton Bridge at Stratford-upon-Avon—

(you can see more of Stratford and the shire—Warwickshire, that is—here: https://www.ourwarwickshire.org.uk/content/catalogue_wow/stratford-upon-avon-clopton-bridge-2 )

the road runs, not surprisingly, due eastwards and here, consulting our map,

is the Old Forest to our right,

described, by our narrator, as Frodo and his friends see it on their detour away from the Great East Road:

“Looking ahead they could see only tree-trunks of innumerable sizes and shapes: straight or bent, twisted, leaning, squat or slender, smooth or gnarled and branched; and all the stems were green or grey with moss and slimy, shaggy growths.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 6, “The Old Forest”)

Keep in mind, however, that we’re seeing it through a long line of trees planted alongside the road, probably as a windbreak.

We know that they’re there because Merry says:

“ ‘That is a line of trees,’ said Merry, ‘and that must mark the Road. All along it for many leagues east of the Bridge there are trees growing. Some say they were planted in the old days.’ “ (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 8, “Fog on the Barrow-downs”)

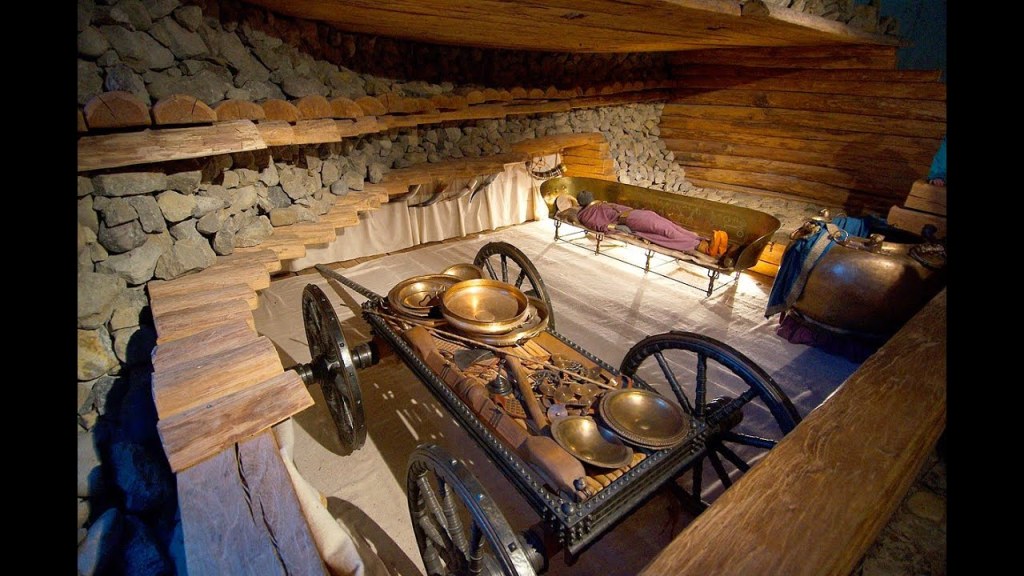

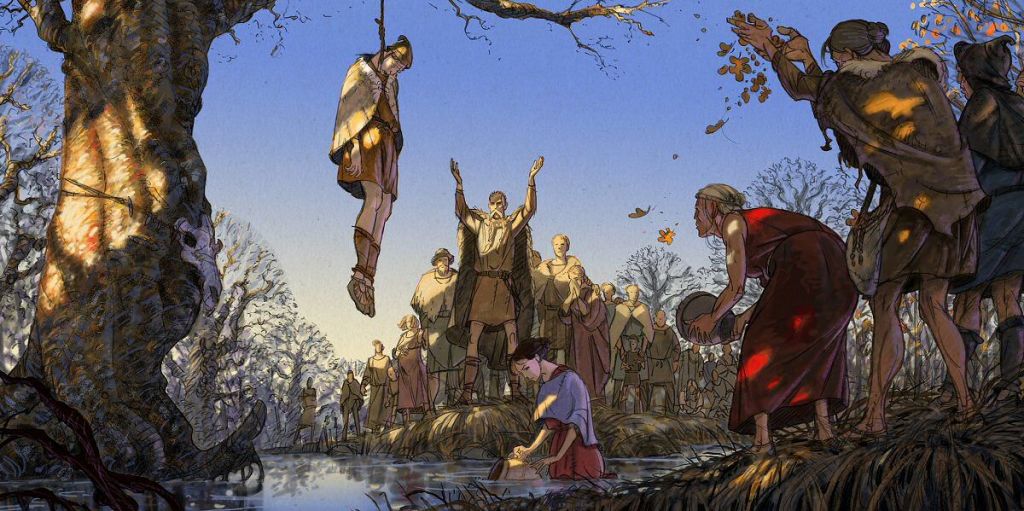

As we travel farther along the road, if we look to our right, through the trees, we then come to the edge of the Barrow-downs,

with their ancient standing stones

and tumuli—

where Frodo and his friends almost end their trip.

(Matthew Stewart)

But we haven’t strayed, as they did, and, passing the Downs, we see, again on our right:

“The dark line they had seen was not a line of trees but a line of bushes growing on the edge of a deep dike, with a steep wall on the further side.”

A dike is a ditch, usually with an earthen embankment made from the spoil of the ditch. There are several of these in England, like Offa’s Dyke—

The narrator adds:

“…with a steep wall on the further side”

and I’m presuming that that is the earthen embankment, with:

“…a gap in the wall” through which Frodo and friends rode and

…when at last they saw a line of tall trees ahead…they knew that they had come back to the Road.”

If you’re read the first part of this posting, you will know that I’ve been assuming that that Road, laid in ancient times to a stone bridge and beyond, would be like a Roman road, and be paved,

if a bit weedy, but now we find:

“…the Road, now dim as evening drew on, wound away below them. At this point it ran nearly from South-west to North-east, and on their right it fell quickly down into a wide hollow. It was rutted and bore many signs of the recent heavy rain; there were pools and pot-holes full of water.”

Does this suggest that it was, at best and in the past, simply a dirt road, through well-kept? Or is it a very run-down road, worn and covered over with leaves and dirt, the ancient blocks gradually becoming separated under the weight of centuries, allowing for pot-holes?

In any event, we now continue our journey with Frodo and his compantions until–

“…they saw lights twinkling some distance ahead.

Before them rose Bree-hill barring the way, a dark mass against misty stars; and under its western flank nestled a large village. Towards it they [and we] now hurried desiring only to find a fire, and a door between them and the night.”

We’re not in Bree yet, however, as:

“The village of Bree had some hundred stone houses of the Big Folk, mostly above the Road, nestling on the hillside with windows looking west. On that side, running in more than half a circle from the hill and back to it, there was a deep dike with a thick hedge on the inner side. Over this the Road crossed by a causeway; but where it pierced the hedge it was barred by a great gate. There was another gate in the southern corner where the Road ran out of the village. The gates were closed at nightfall; but just inside them were small lodges for the gatekeepers.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 9, “At the Sign of the Prancing Pony”)

We’ve seen a dike just now, at the Great East Road, but now we have to add a hedge

and a gate.

Once inside, however, lies the Prancing Pony

(Ted Nasmith)

and one more pint before bed.

As always, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

Read road signs carefully,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O