As always, welcome, dear readers.

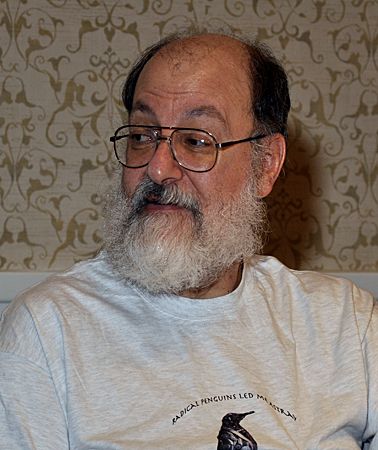

Currently, I’m rereading the invaluable Douglas Anderson’s Tales Before Tolkien.

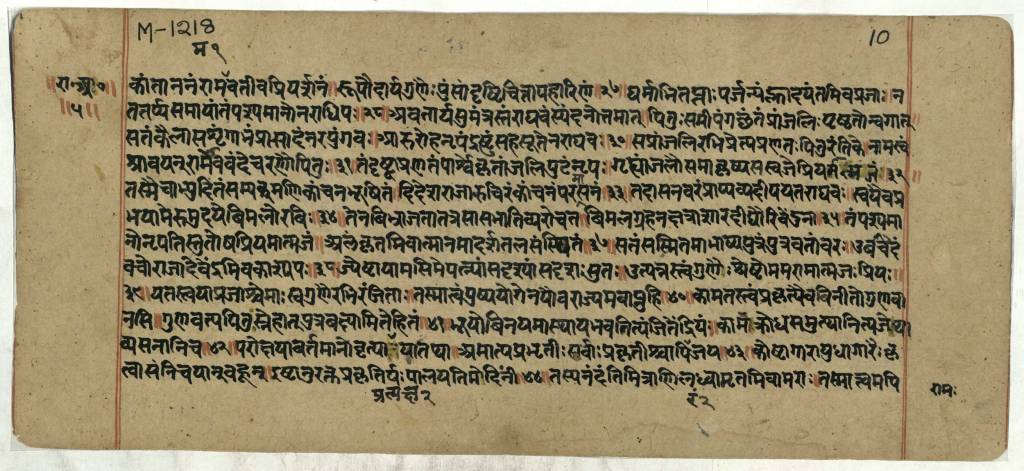

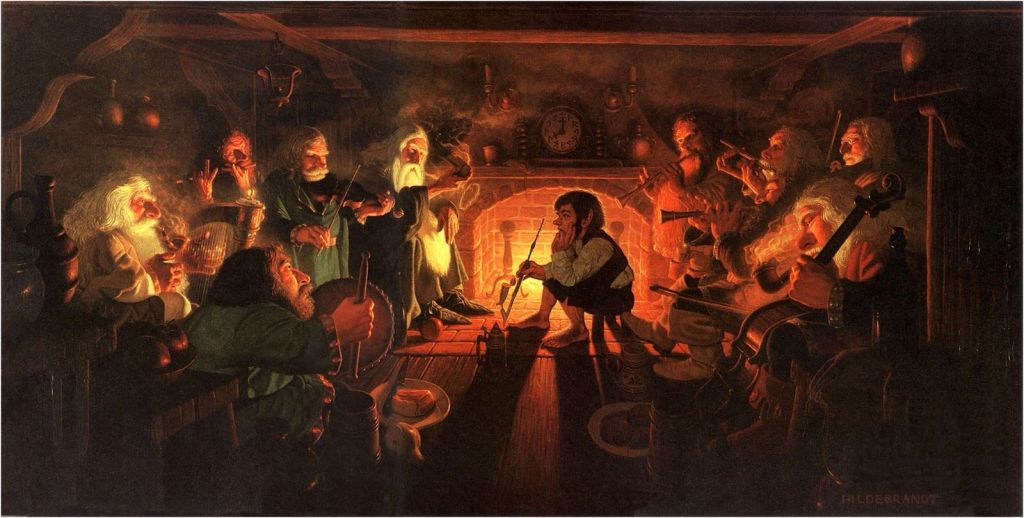

I had first known Anderson’s work through the reason I’ve called him “invaluable”—this—

which I recommend to anyone interested in deepening her/his knowledge of The Hobbit. In Tales, Anderson provides us with a selection of short stories (one, at least, H. Rider Haggard’s “Black Heart and White Heart: A Zulu Idyll” being so long as maybe even to be considered a novella) which JRRT might have read or had read to him, based upon his own or other’s testimony, as well as stories with themes which appear in his work and which, although we have no evidence for them, he might have known.

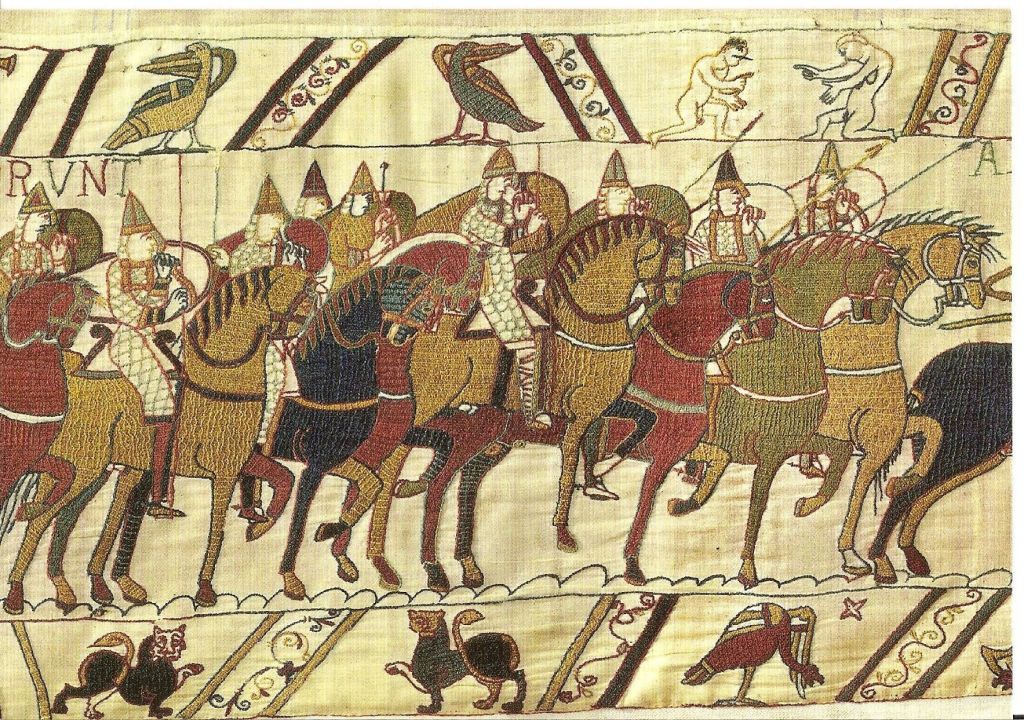

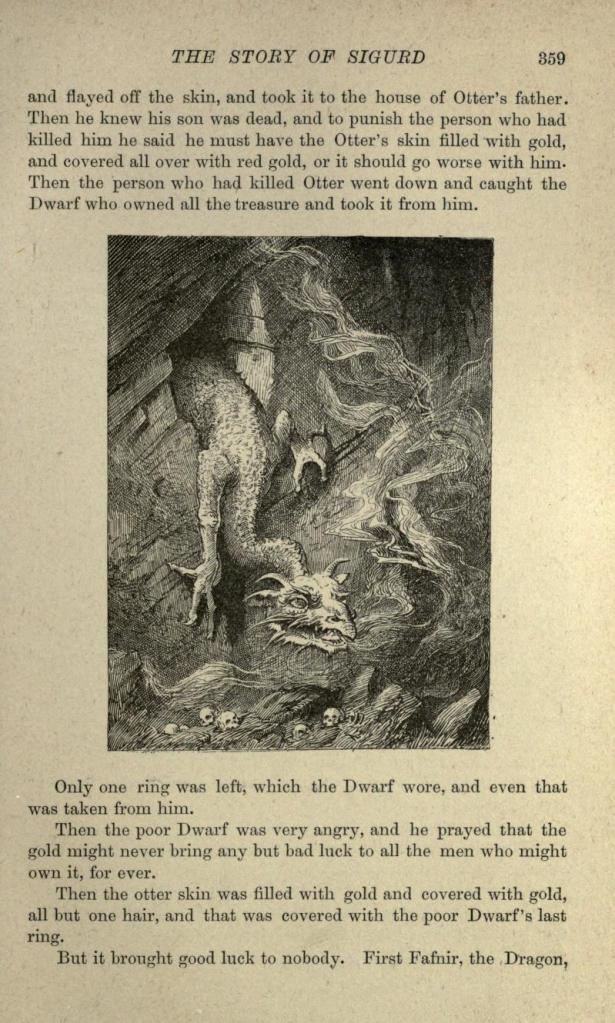

One story which fits the first category is from Andrew Lang’s The Red Fairy Book (1890),

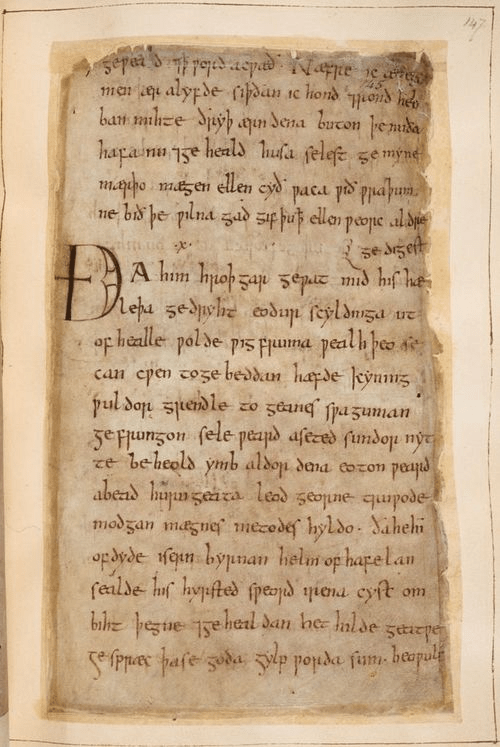

Lang’s retelling of “The Story of Sigurd”.

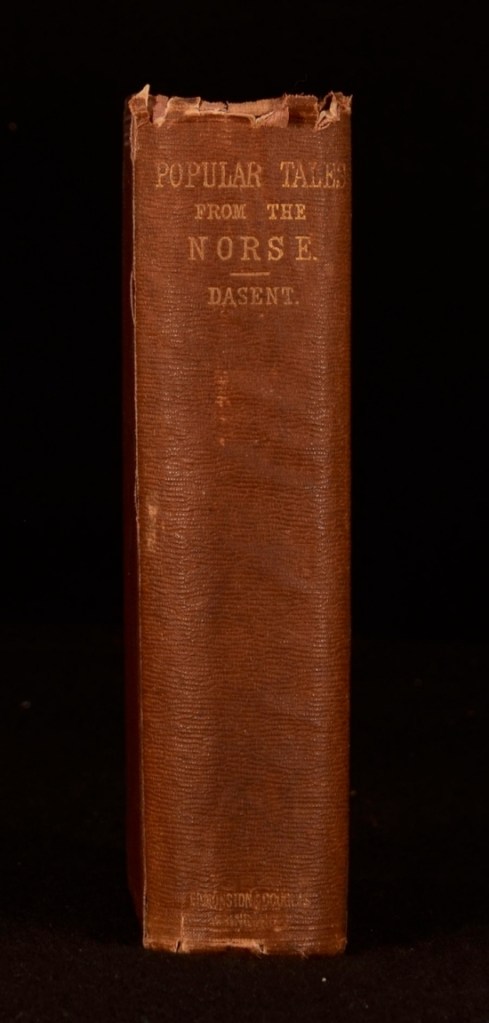

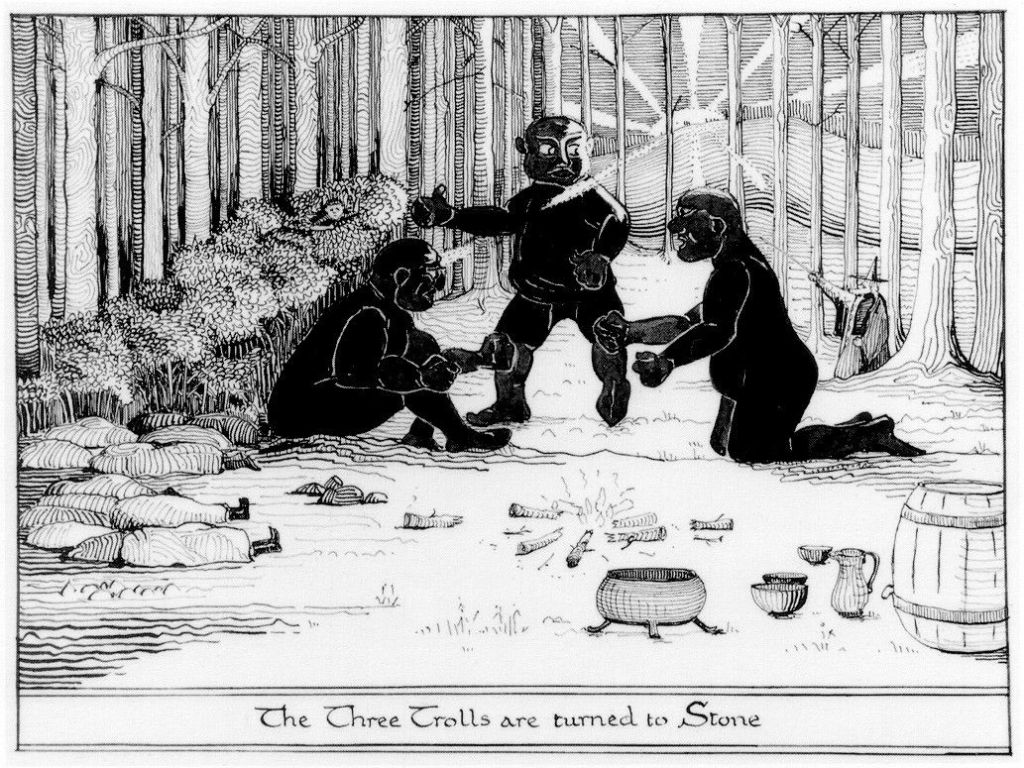

Initially, we might have a pretty good idea that Tolkien was acquainted with this book from the title of a previous story in it, “Soria Moria Castle”, which he mentions in a letter to “Mr. Rang” (“drafts for a letter to ‘Mr. Rang’, August, 1967, Letters, 541, although there he credits George Webb Dasent’s Popular Tales from the Norse, 1859, from which Lang reprinted and edited it, of which you can read the second edition here: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/8933/8933-h/8933-h.htm ) but the Sigurd story seems to me the real giveaway:

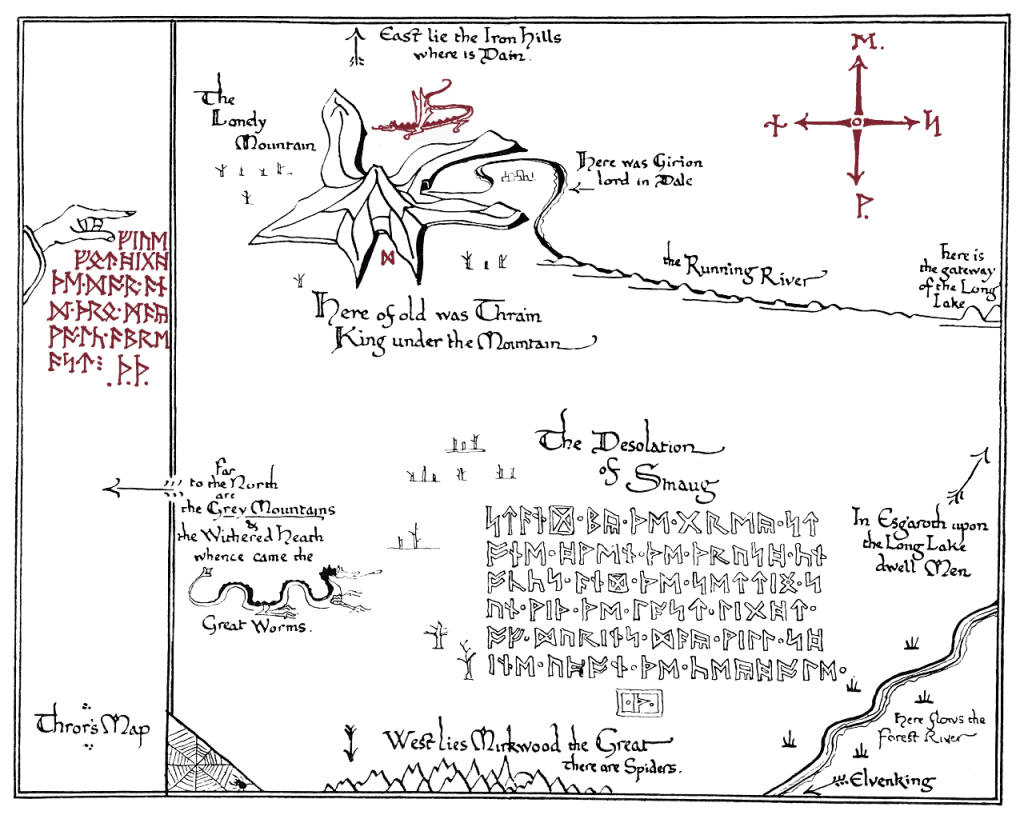

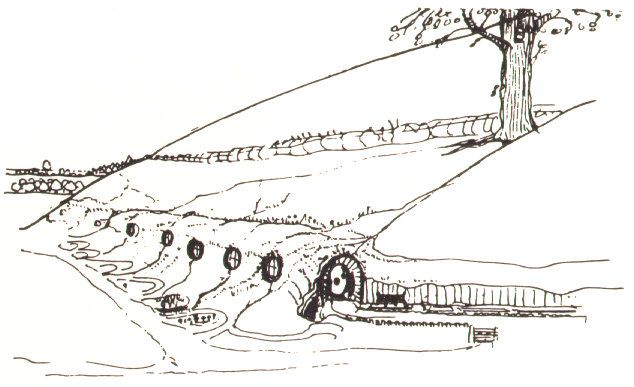

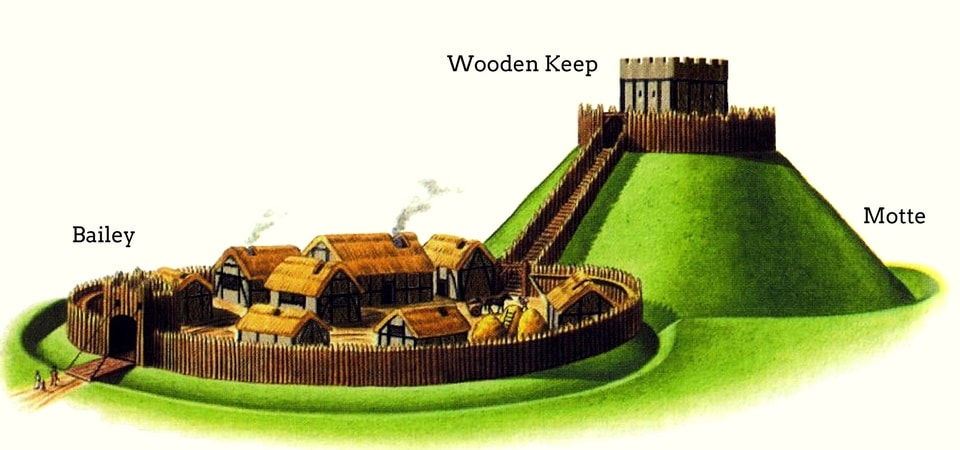

1. it has a talking dragon, Fafnir, who “wallows” on a mound of gold, as well as a horse with a noble pedigree

2. but perhaps even more convincing, it has a sword which, once broken, its sherds are carefully preserved and reforged and which then prove that dragon’s doom (The sword is called Gram, which, in the Old Norse form, “gramr”, means “wrath”, according to Cleasby and Vigfusson’s 1874 An Icelandic-English Dictionary—in modern German, “Gram” means “grief/sorrow”—clearly what happens when wrath takes action—as in the case of this dragon)

Was it this story which produced this anecdote?

“Somewhere about six years old I tried to write some verses on a dragon about which I now remember nothing except that it contained the expression a green great dragon…” (taken from notes attached to a letter of 30 June, 1955, written to Houghton Mifflin, Letters, 321—Tolkien adds a little to this in a letter to W.H. Auden, 7 June, 1955, Letters, 313)

Wherever the influence came from, it was a strong one upon Tolkien—but there was a kind of realism attached, as well:

“I desired dragons with a profound desire. Of course, I in my timid body did not wish to have them in the neighbourhood, intruding into my relatively safe world, in which it was, for instance, possible to read stories in peace of mind, free from fear. But the world that contained even the imagination of Fafnir was richer and more beautiful, at whatever cost of peril.” (“On Fairy Stories”—in this edition—The Monsters and the Critics, Harper/Collins, 2006–135)

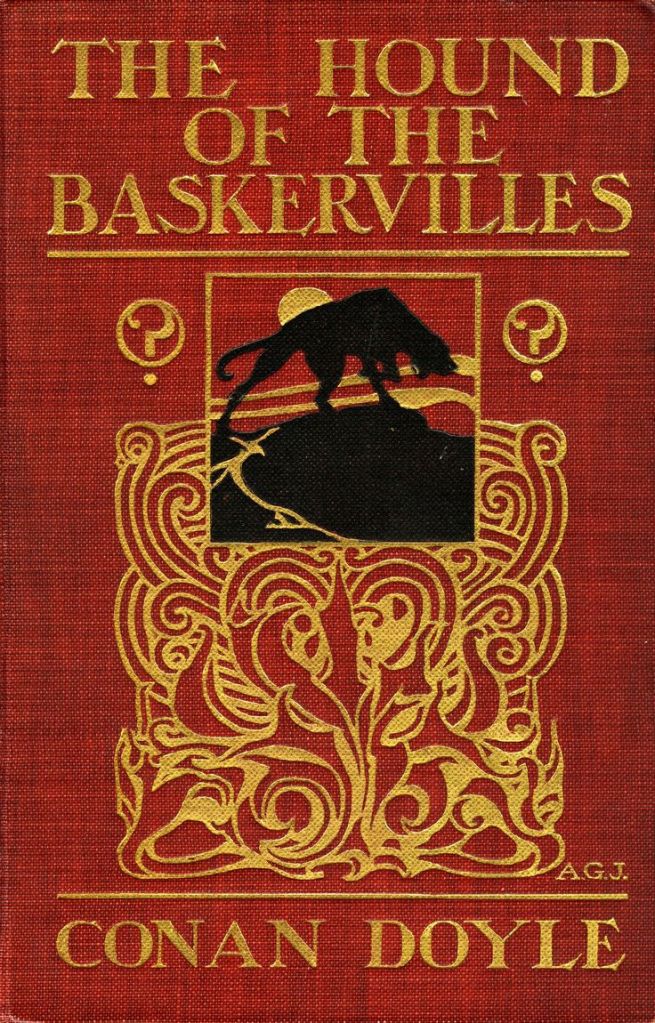

“Never laugh at live dragons, Bilbo you fool!” (The Hobbit, Chapter 12, “Inside Information”) might have been written by the young JRRT, but the second dragon story in Anderson’s collection is in sharp contrast to the tragedy of the life and death of Sigurd: E. Nesbit’s “The Dragon Tamers”. E(dith) Nesbit (1858-1924)

was a popular English children’s author of the late-Victorian/Edwardian era, both an imaginative and witty one (she also wrote for adults) and this story reflects that combination. As you can read it for yourself here in The Book of Dragons (1901): https://www.gutenberg.org/files/23661/23661-h/23661-h.htm , I’ll only say that it’s a story in which a dragon is outwitted by a blacksmith and which has writing like this:

“But the dragon was too quick for him—it put out a great claw and caught him by the leg, and as it moved it rattled like a great bunch of keys, or like the sheet-iron they make thunder out of in pantomimes.

‘No, you don’t,’ said the dragon, in a spluttering voice, like a damp squid. [firecracker]

‘Deary, deary me,’ said poor John, trembling more than ever in the clasp of the dragon; ‘here’s a nice end for a respectable blacksmith!’

The dragon seemed very much struck by this remark.

‘Do you mind saying that again?’ said he, quite politely.

So John said again, very distinctly: ‘Here-Is-A-Nice-End-For-A-Respectable-Blacksmith.’

‘I didn’t know,’ said the dragon. ‘Fancy now! You’re the very man I’ve wanted.’

“So I understood you to say before,’ said John, his teeth chattering.

‘Oh, I don’t mean what you mean,’ said the dragon, ‘but I should like you to do a job for me. One of my wings has got some of the rivets out of it just above the joint. Could you put that to rights?’ “

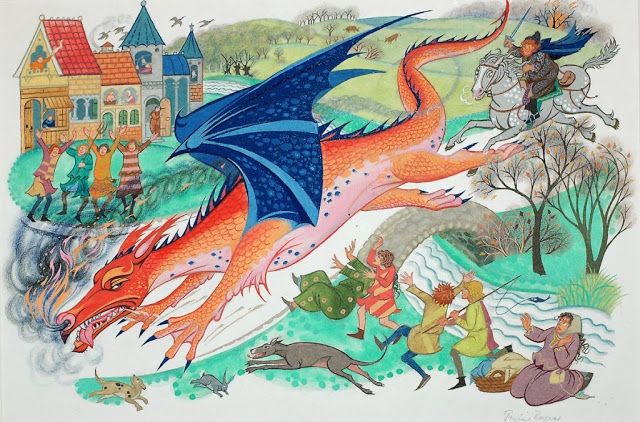

At first, I wasn’t sure how “The Dragon Tamers” fit into Anderson’s schema for his selections: dragon, yes, but a live dragon one might laugh at or at least about? But then I thought about Tolkien’s Farmer Giles of Ham (1949).

Besides a pesky giant, the title character has to deal with the splendidly-named “Chrysophylax Dives”—“Goldguard the Wealthy”

and not only do we have a talking dragon (and a blacksmith—although he’s rather a negative minor character), but we have comedy again. Giles has captured Chrysophylax and made him agree to pay a ransom—which the dragon reneges upon. Giles is then nominated by the king to track him—and the ransom—down. Giles does so and the haggling (at least on the dragon’s part) begins–

“ ‘You’re nigh on a month late,’ said Giles, ‘and payment is overdue. I’ve come to collect it. You should beg my pardon for all the bother I’ve been put to.’

‘I do indeed!’ said he. ‘I wish that you had not troubled to come.’

‘It’ll be every bit of your treasure this time, and no market-tricks,’ said Giles, ‘or dead you’ll be, and I shall hang your skin from our church steeple as a warning.’

‘It’s cruel hard!’ said the dragon.

‘A bargain’s a bargain,’ said Giles

‘Can’t I just keep a ring or two, and a mite of gold, in consideration of cash payment?’ said he.”

Imagine Smaug trying to make a deal!

And here—as I entitled this “Three Dragons… “ after all—I want to add to Anderson’s list one more comic dragon, an unnamed by very talkative one in a short story by Kenneth Grahame (1859-1932).

You may know him from his The Wind in the Willows (1908).

(And I can’t resist adding that you can acquire your own copy of E.H. Shepard’s illustrated edition—my favorite—here: https://archive.org/details/the-wind-in-the-willows-grahame-kenneth-1859-1932-sh/mode/2up )

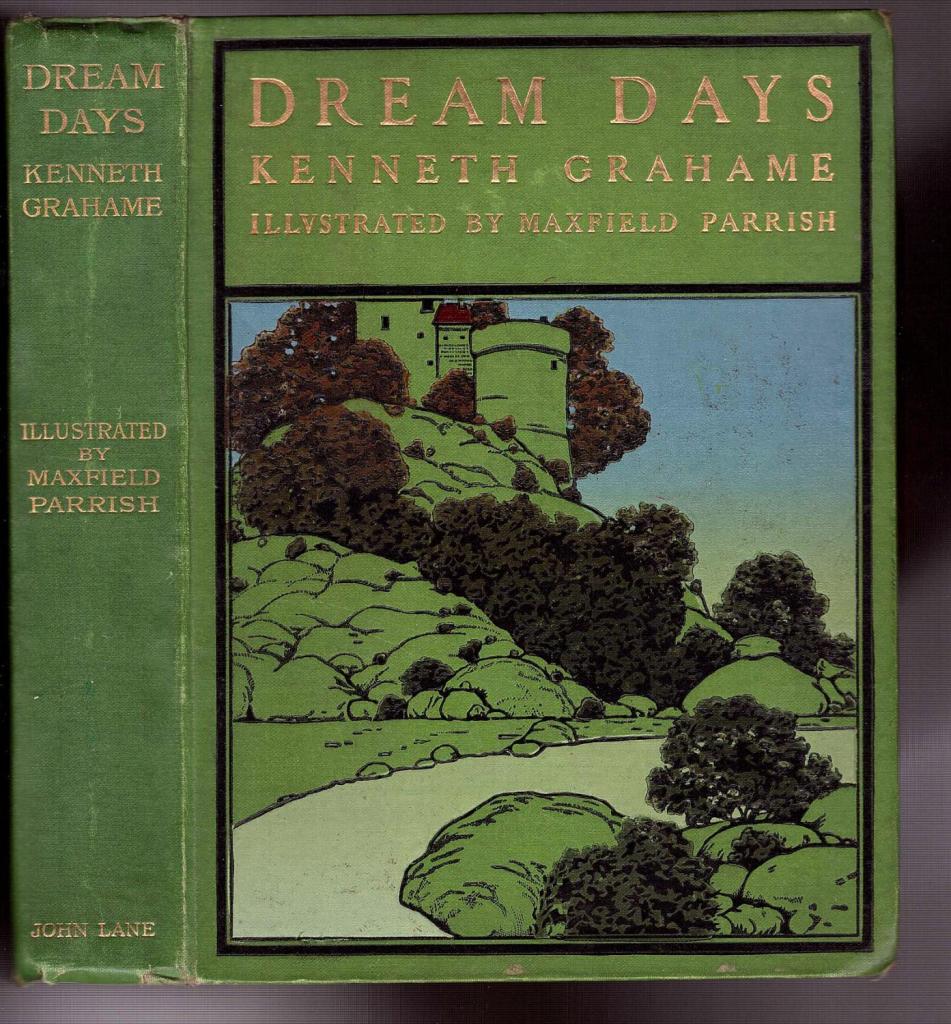

This story, “The Reluctant Dragon”, was published in Grahame’s 1898 collection Dream Days

and I think that the title alone gives you an idea that this is not going to be a Fafnir/Sigurd tragedy any more than “The Dragon Tamers” or “Farmer Giles”. This is, in fact, a poetry-loving creature who, when accosted by Saint George, absolutely declines to fight—until he collaborates on fixing the match, which the dragon enjoys immensely:

“The dragon was employing the interval in giving a ramping-performance for the benefit of the crowd. Ramping, it should be explained, consists in running round and round in a wide circle, and sending waves and ripples of movement along the whole length of your spine, from your pointed ears right down to the spike at the end of your long tail. When you are covered with blue scales, the effect is particularly pleasing; and the Boy recollected the dragon’s recently expressed wish to become a social success.”

Once the match is over and the dragon has “died”, he is revived and Saint George makes a speech to the villagers (some of whom had actually bet on the dragon) about how the dragon is now a repentant beast and promises to be good ever afterwards and there’s a banquet. Again, a far cry from Fafnir/Sigurd, but certainly in line with “The Dragon Tamers” and Farmer Giles. (And you can read it here: https://archive.org/details/dreamdays00grahuoft/page/176/mode/2up )

Now what about that griffon? It’s in “The Griffon and the Minor Canon” and

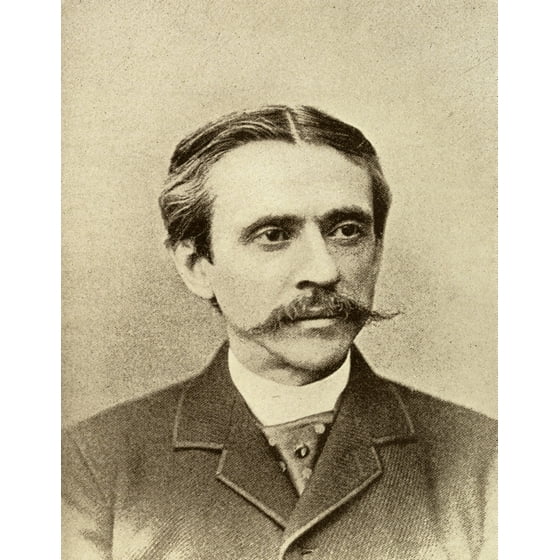

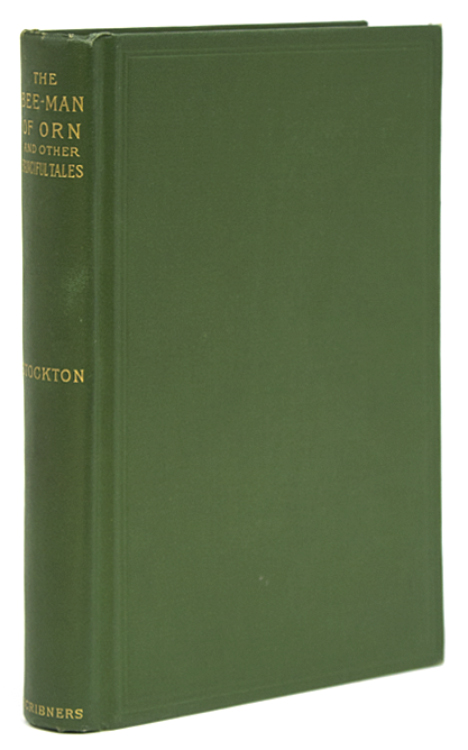

Anderson includes it from Frank Stockton’s (1834-1902)

1887 collection, The Beeman of Orn and Other Fanciful Tales, which you’ll find here: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/12067/12067-h/12067-h.htm

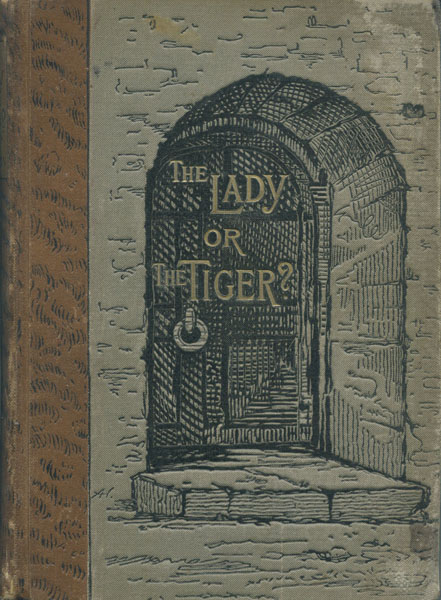

If you recognize the name “Frank Stockton”, you’ve probably read another of his stories “The Lady, Or the Tiger?” from the 1884 The Lady, Or the Tiger? And Other Stories—available here: https://archive.org/details/ladyortigerando01stocgoog/page/n4/mode/2up

As in the case of “Tamers”, Giles, and “Reluctant”, the monster of the title comes to a small village, but, instead of planning a feast, he is there to view a carving of a griffon over the local church door, which makes him sound more like the unnamed reluctant dragon than the others.

The villagers are terrified when he makes inquiries and it’s only the minor canon (a kind of junior clergyman) who, even nervous, is willing to talk with the griffon. The griffon stays in the village and bonds with the canon and even rescues him at one point from a kind of martyrdom in the wilderness, but it’s rather a sad little tale, well told, but this is the one story which I have difficulty in understanding its possible connection with JRRT. As it’s in the collection for which I’ve posted an address above, read it for yourself and see what you think.

And, as you read, think about what Tolkien had written, and which I cited earlier:

“I desired dragons with a profound desire. Of course, I in my timid body did not wish to have them in the neighbourhood, intruding into my relatively safe world, in which it was, for instance, possible to read stories in peace of mind, free from fear. But the world that contained even the imagination of Fafnir was richer and more beautiful, at whatever cost of peril.” (“On Fairy Stories”—in this edition—The Monsters and the Critics, Harper/Collins, 2006–135)

As ever, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

Remember that, with some dragons, it can be a laughing matter,

And remember, as well, that there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

With this—posting #521—we begin our eleventh year together, dear readers. Thank you, as always, for your support. Together, may we have just as many years of reading and writing about adventure and fantasy—at least—in the future.