Tags

Bishop Odo of Bayeux, club, Eowyn, Fantasy, lord-of-the-nazgul, lotr, Mace, Merry, Teddy Roosevelt, theodore-roosevelt, Tolkien

Welcome, as always, dear readers.

So many earlier events are tied to this scene:

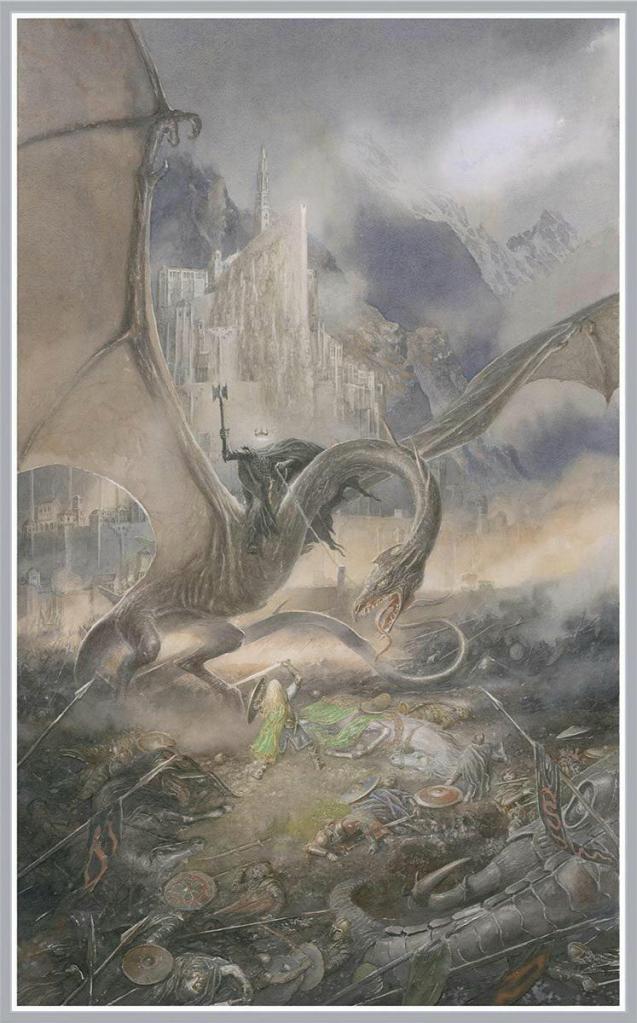

“The great shadow descended like a falling cloud…Upon it sat a shape, black-mantled, huge and threatening.”

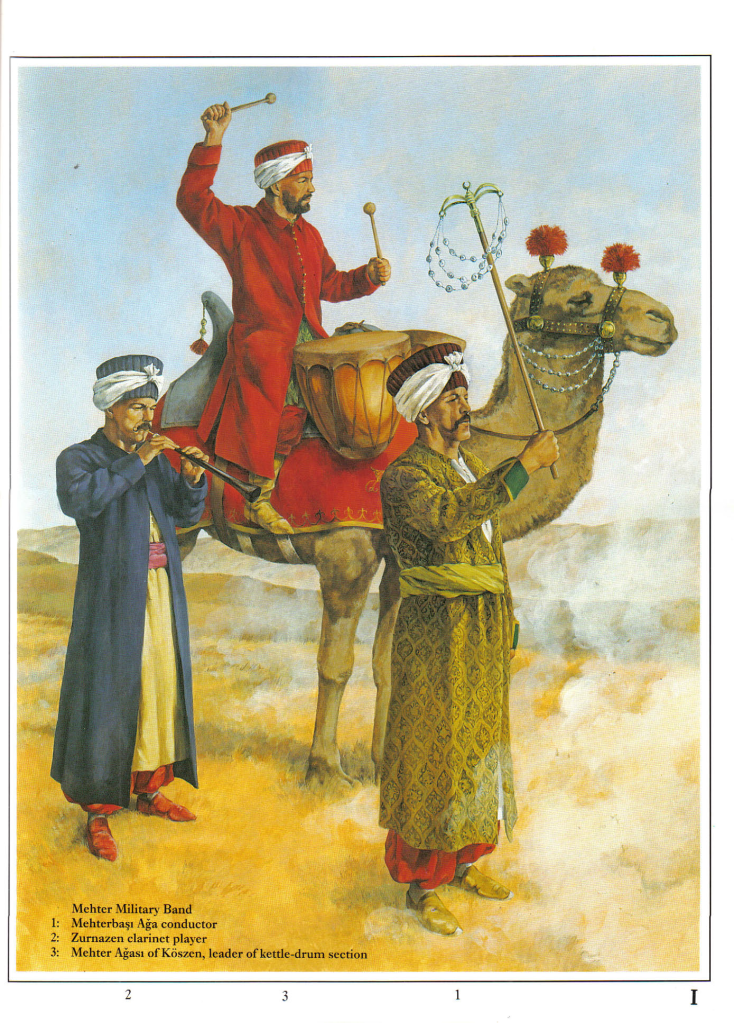

It’s Eowyn about to challenge the Witch King of Angmar, the chief of the Nazgul, mounted upon his really disgusting creature. Behind it lie:

1. the Black Riders

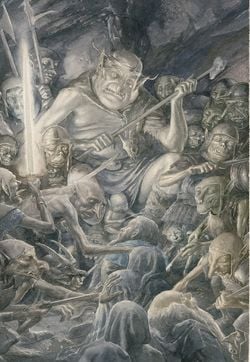

(the Gaffer and a Nazgul—perfectly captured by Denis Gordeev)

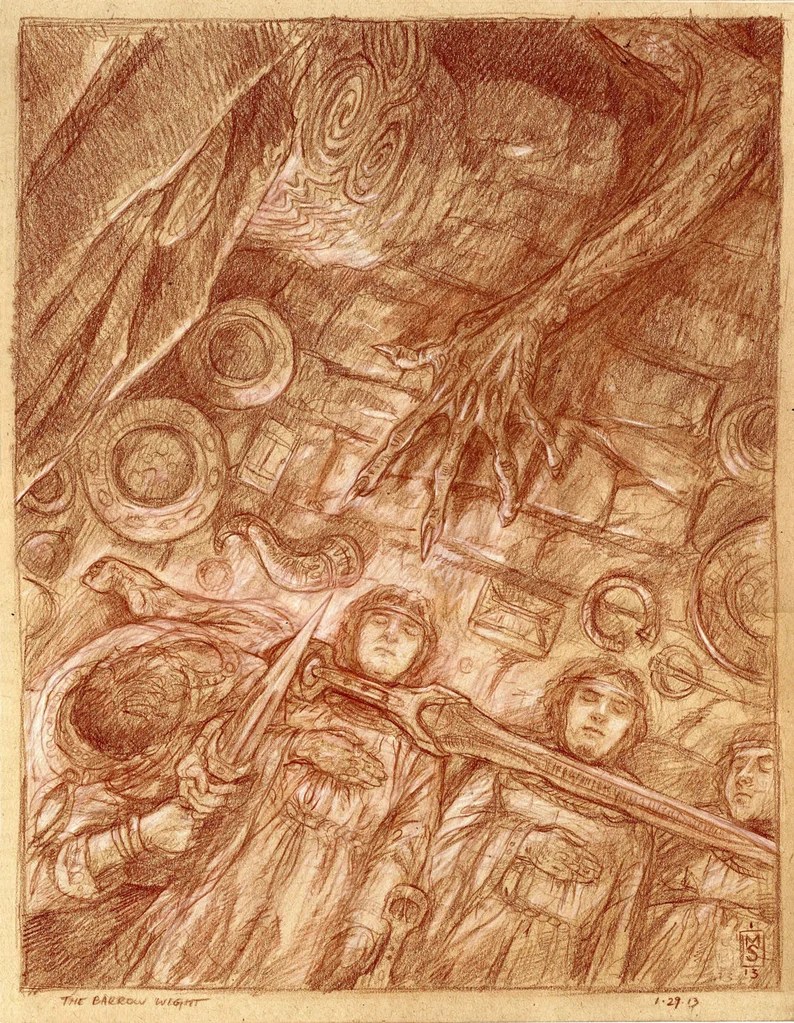

2. a sword taken from the barrow where the Barrow Wight almost makes an early end to the story

(a sketch for a painting by Matthew Stewart. You can see more of his work here: https://mattstewartartblog.blogspot.com/ )

3. Merry swearing fealty to Theoden

(a statue group from a Dutch site called “Odd World”: https://www.oddworld.be/the-lord-of-rings-merry-and-theoden-miniatuur-beeld-1_prod11508.html

4. Eowyn, in despair over her unrequited love for Aragorn, disguising herself as “Dernhelm”, and taking Merry with her to Minas Tirith

(another Matthew Stewart)

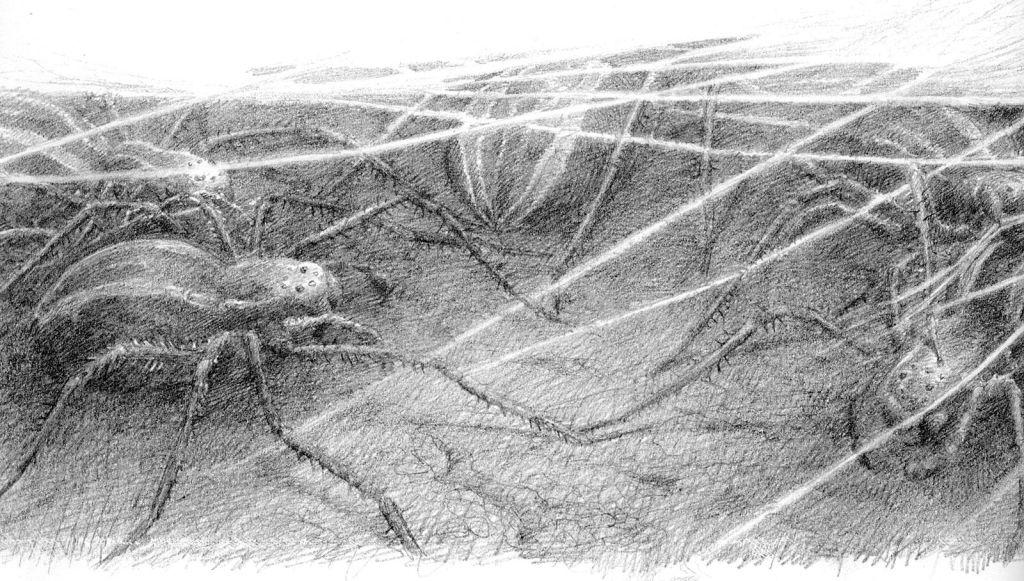

5. one of those disgusting creatures

(Alan Lee)

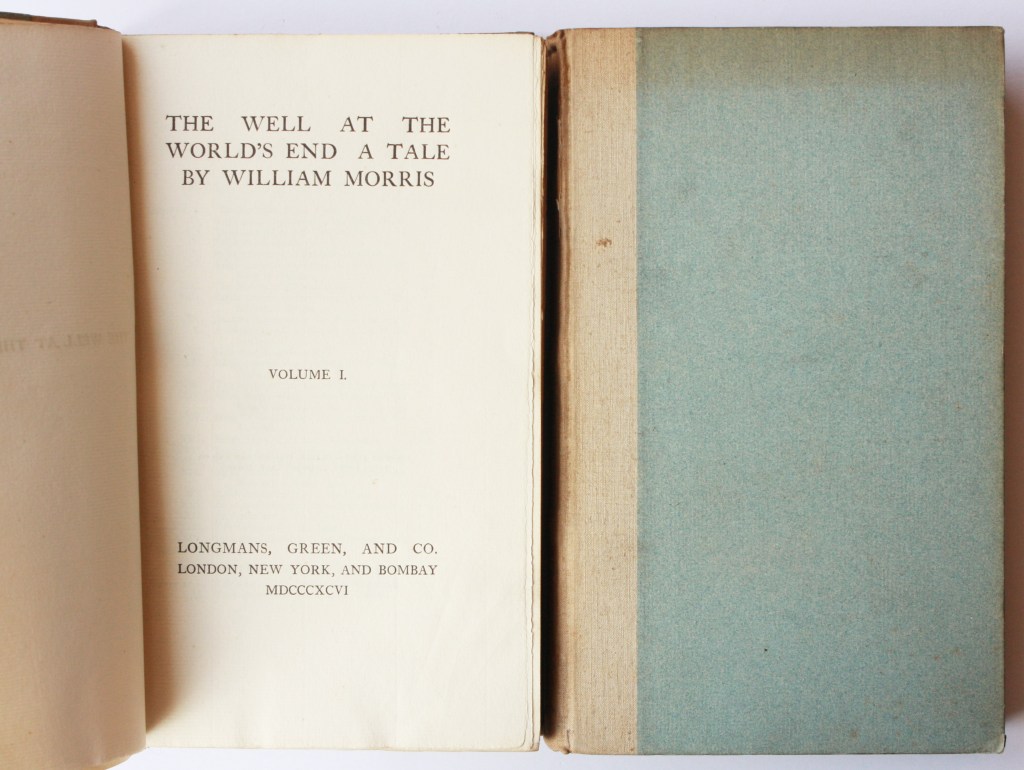

And I’m sure that you can think of more, as it’s a wonderfully rich dramatic scene, including Tolkien at his archaizing best (William Morris would be very pleased with him):

“Begone, foul dwimmerlaik, lord of carrion!”

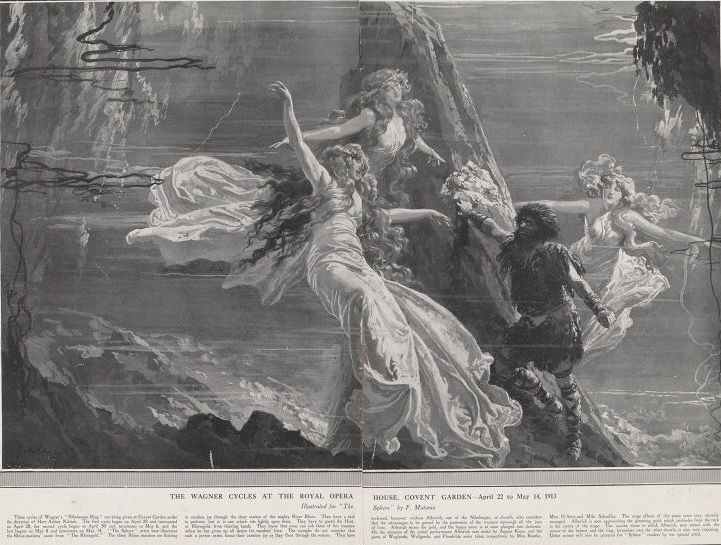

As you can imagine, there are numerous illustrations of it—from the Hildebrandts

to Alan Lee

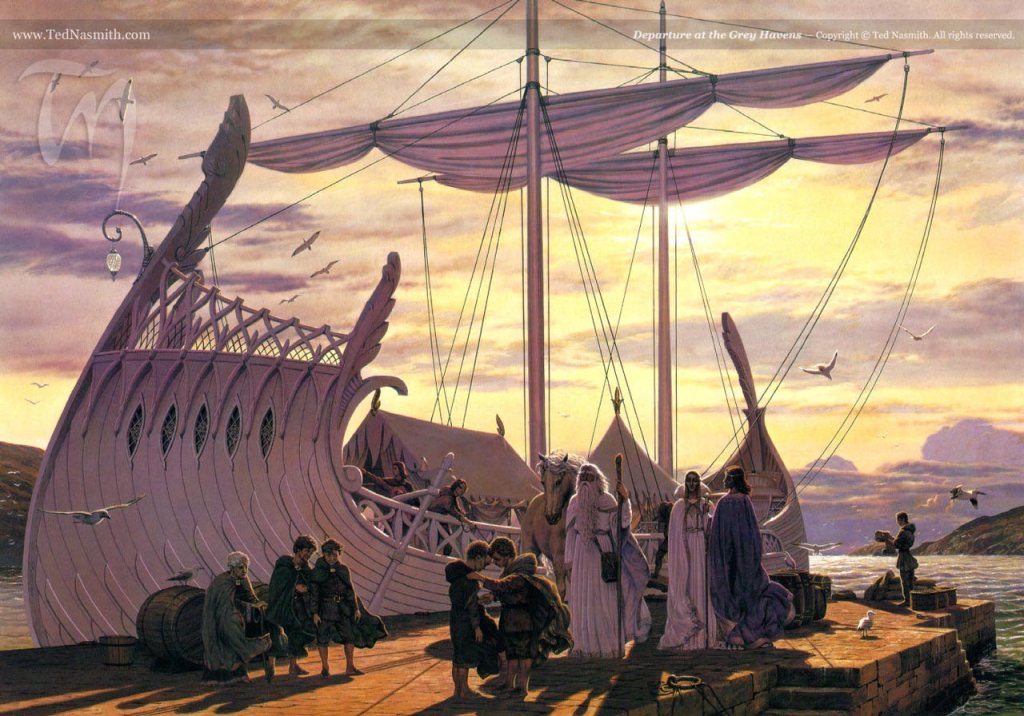

to Ted Nasmith

to Denis Gordeev—

In each case, it’s interesting to see what moment in the scene each artist has chosen. What caught my eye this time, however, wasn’t a person or creature or even the action, but an object:

“…the Lord of the Nazgul. To the air he had returned, summoning his steed ere the darkness failed, and now he was come again, bringing ruin, turning hope to despair, and victory to death. A great black mace he wielded.”

If you knew nothing about weaponry, you’d know that, at least, it’s a weapon, if, for no other reason,from its effect:

“With a cry of hatred that stung the very ears like venom he let fall his mace. Her shield was shivered in many pieces, and her arm was broken…” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 6, “The Battle of the Pelennor Fields”)

If you look up “mace” in Wikipedia, you find a wide variety of possibilities, however, everything from a spice

to a kind of tear gas

to a Star Wars character

(I’m afraid that I don’t have an artist for this, but how could I resist such a wonderful depiction?)

and more—which you can investigate here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mace –but it’s the weapon which I was interested in.

We have earlier seen Nazgul armed with swords:

“There were five tall figures: two standing on the lip of the dell, three advancing. In their white faces burned keen and merciless eyes; under their mantles were long grey robes; upon their grey hairs were helms of silver; in their haggard hands were swords of steel.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 11, “A Knife in the Dark”)

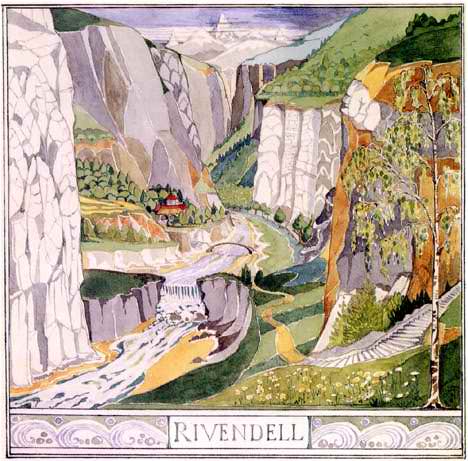

(Weathertop by Alan Lee)

And, of course, at least one dagger—the Morgul Knife which wounds Frodo.

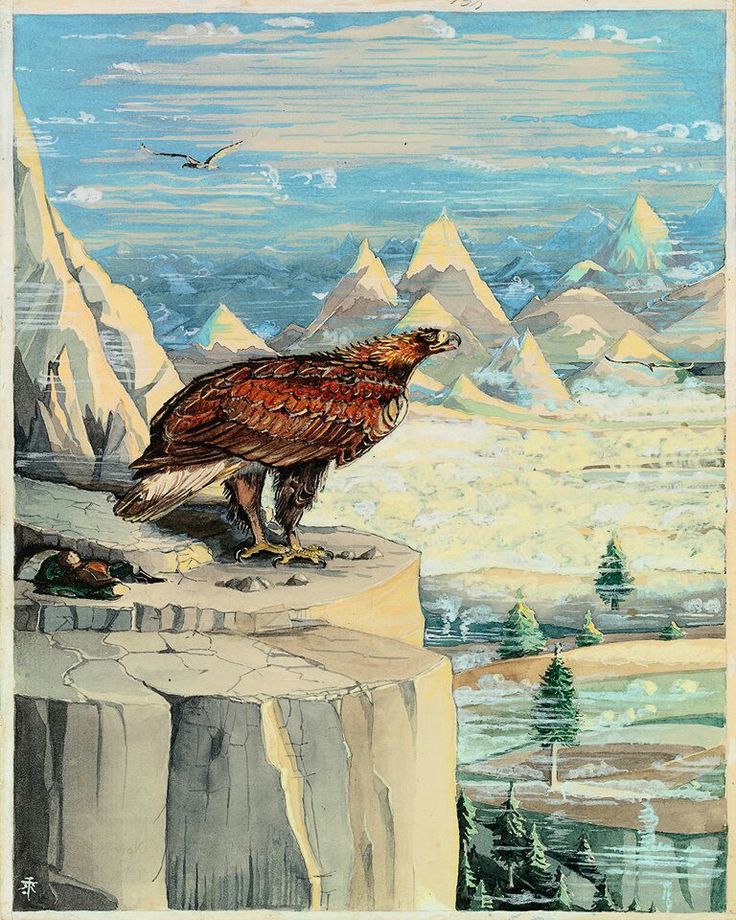

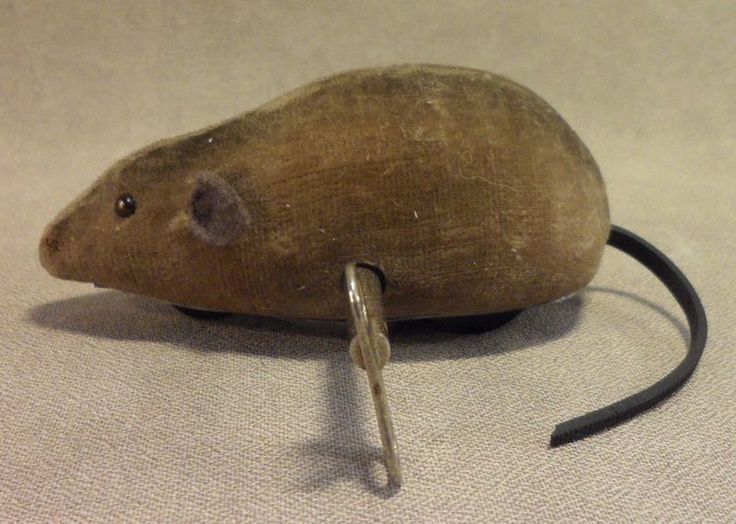

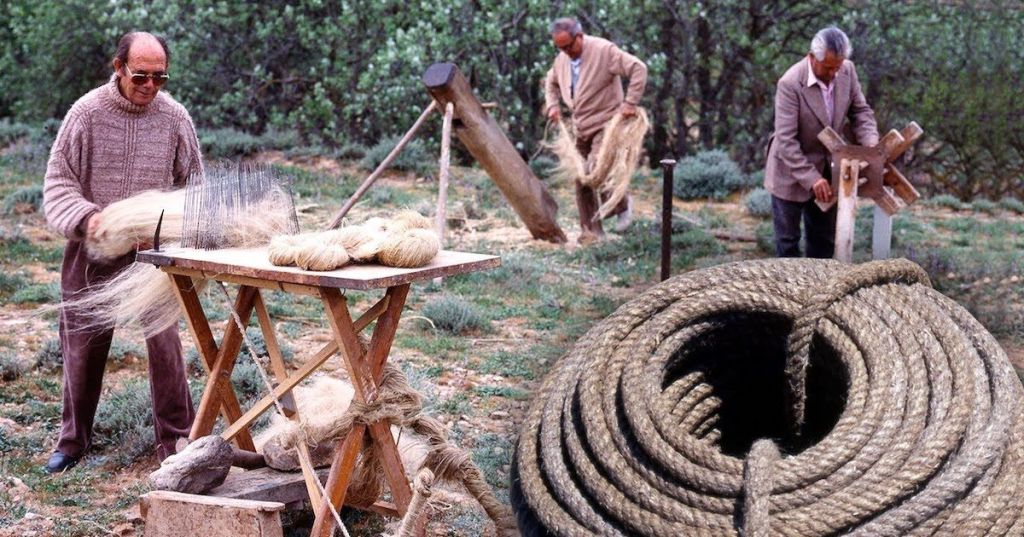

The mace, however, is new—but, in fact, very old. It’s a kind of club, originally probably nothing more than the sort of thing which Herakles carries.

(a rather sea-sick looking Herakles, sailing in the cup of Helios)

When it comes to violence, however, people are endlessly inventive and, by the time of the Egyptians, we find polished stone heads

which, when attached to a stick, became a favorite early bashing weapon.

(from the so-called “Narmer palette”—31st century BC—this is an interesting find from 1894 from the ancient Egyptian site of Nekhen—you can read more about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hierakonpolis )

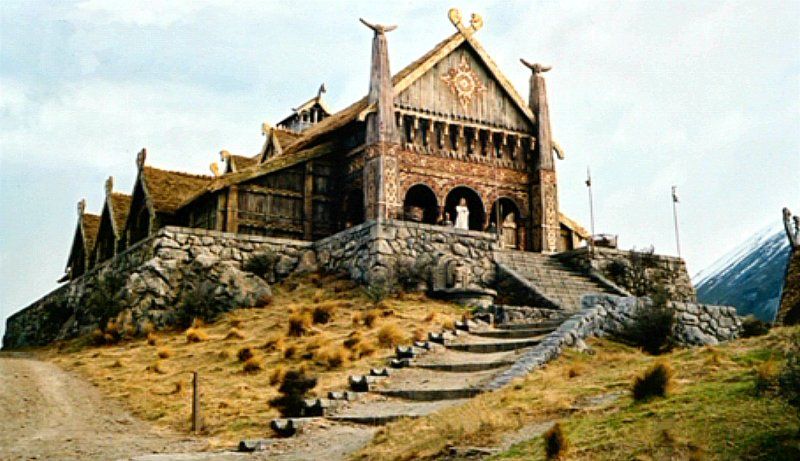

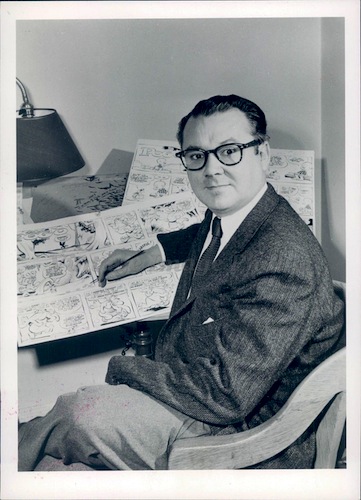

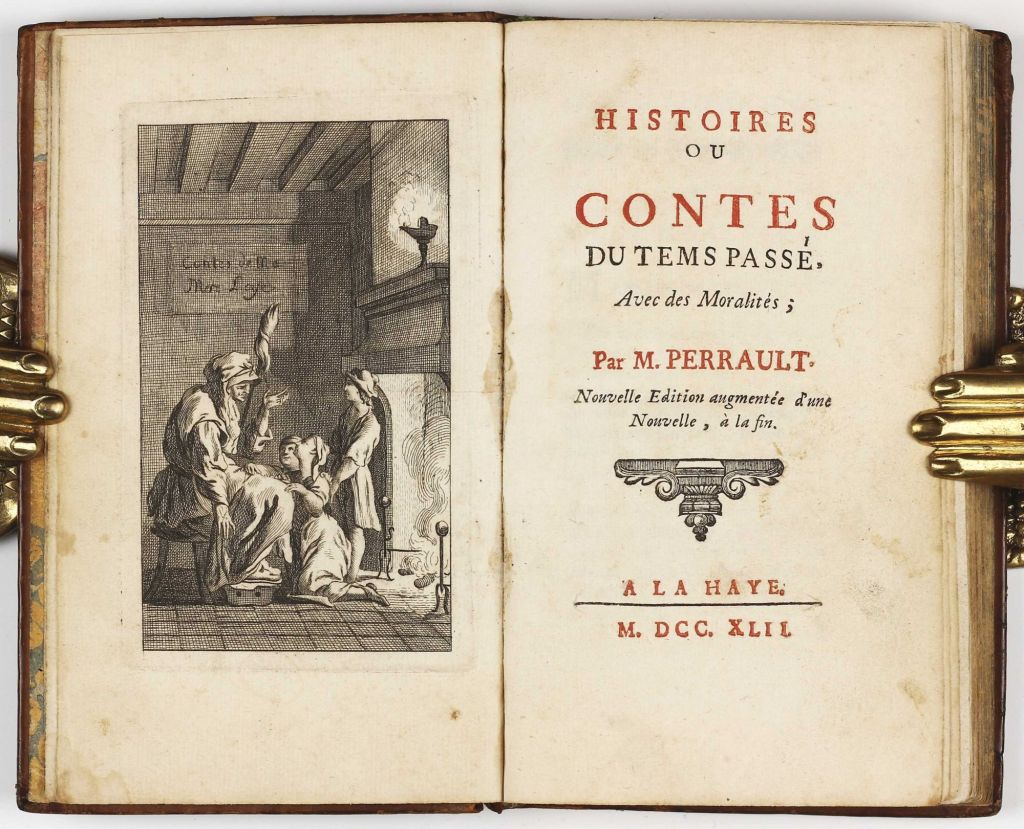

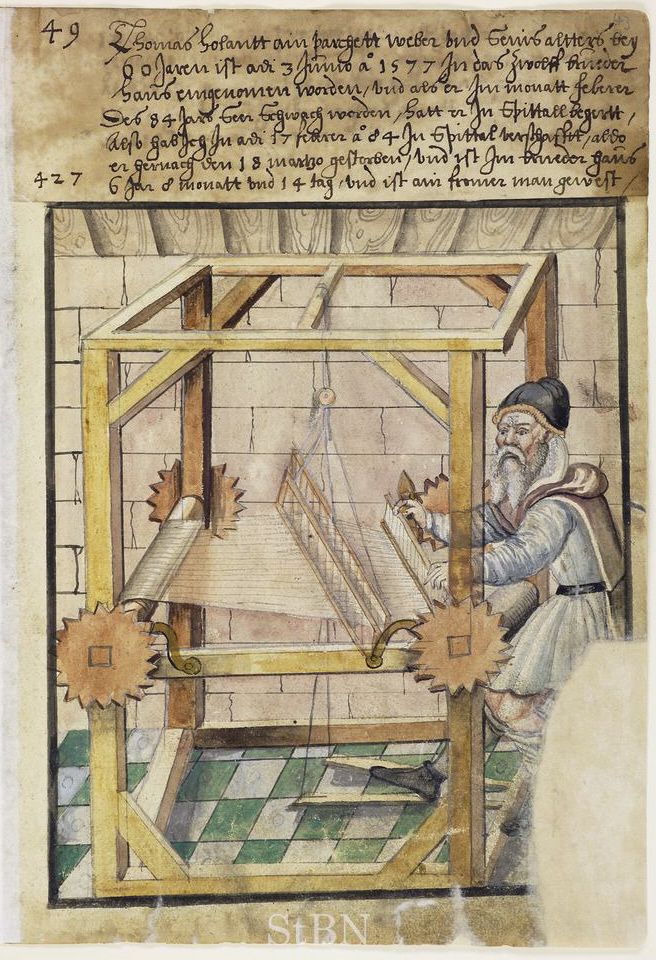

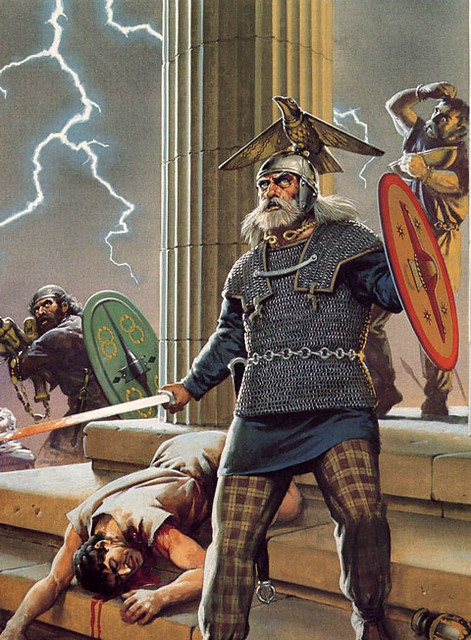

Tolkien’s model, however, would have come from a much later, probably medieval, period and the fact that it’s black might indicate that it’s made of iron. Of course there’s one medieval wooden club which JRRT would have known—

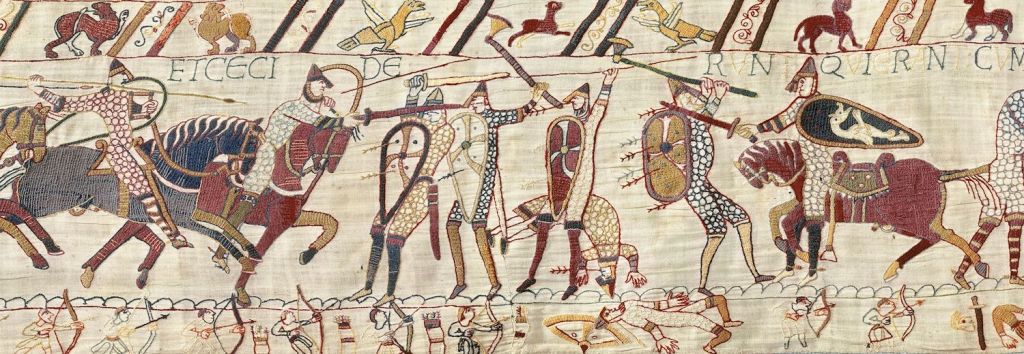

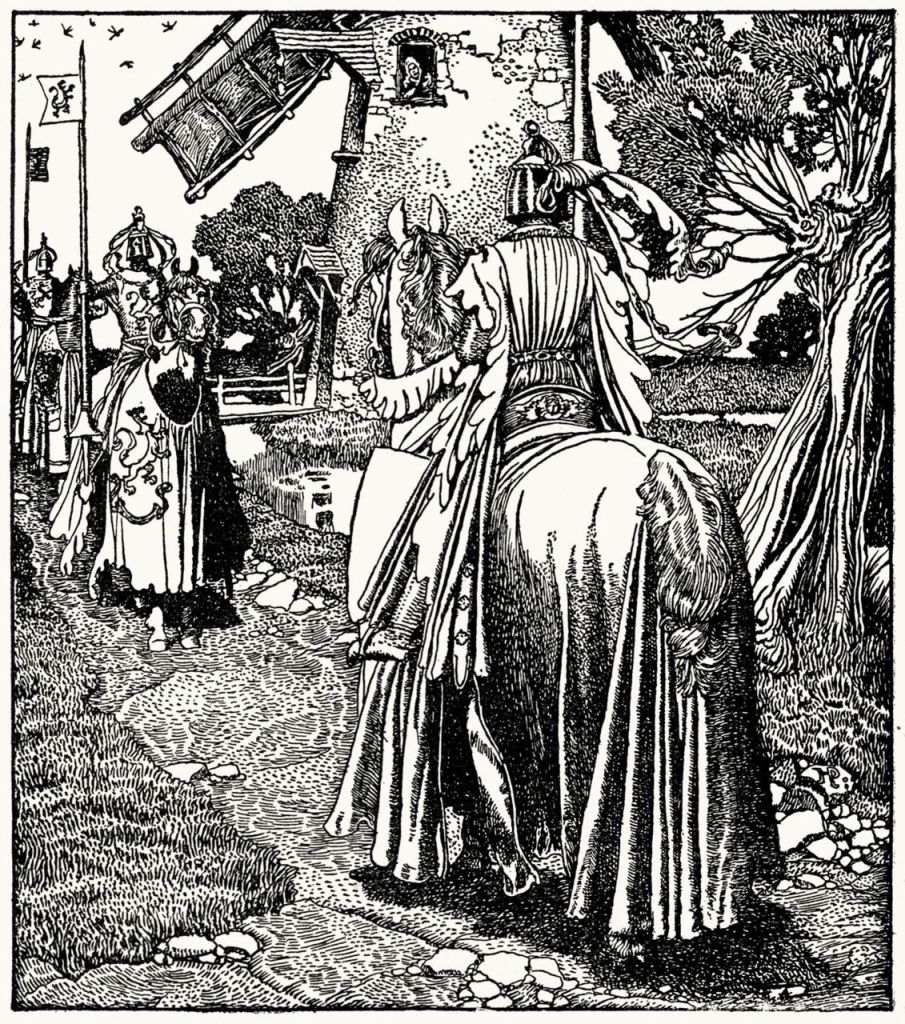

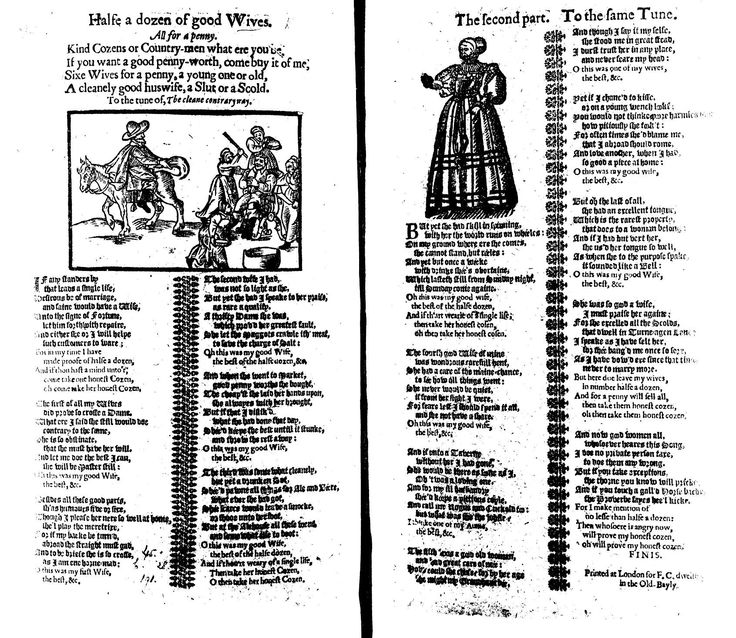

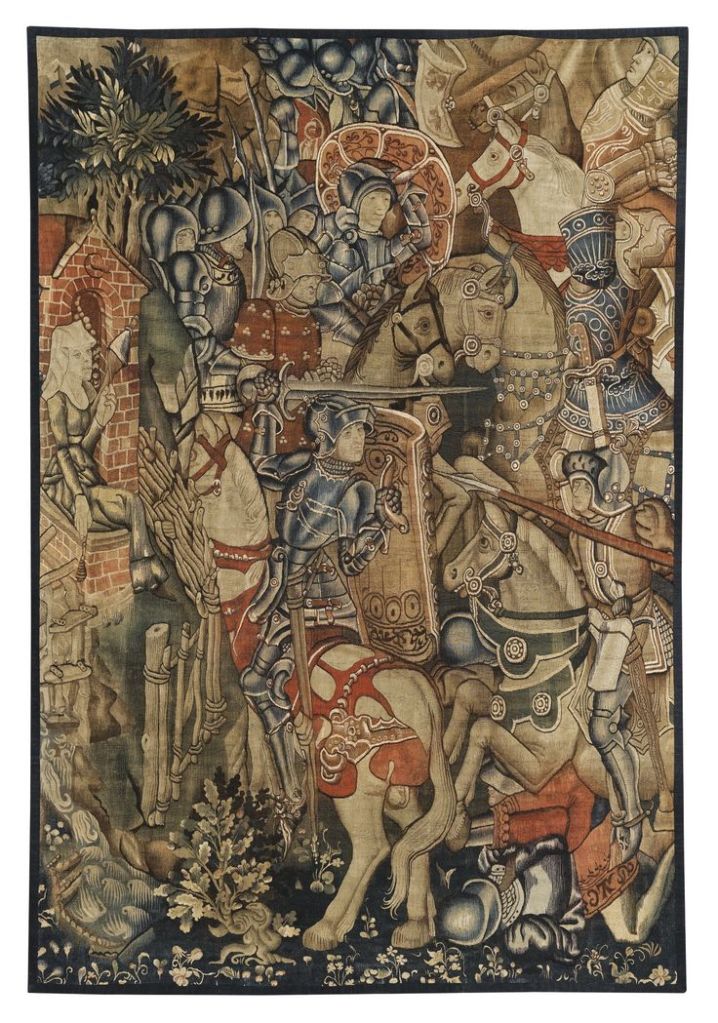

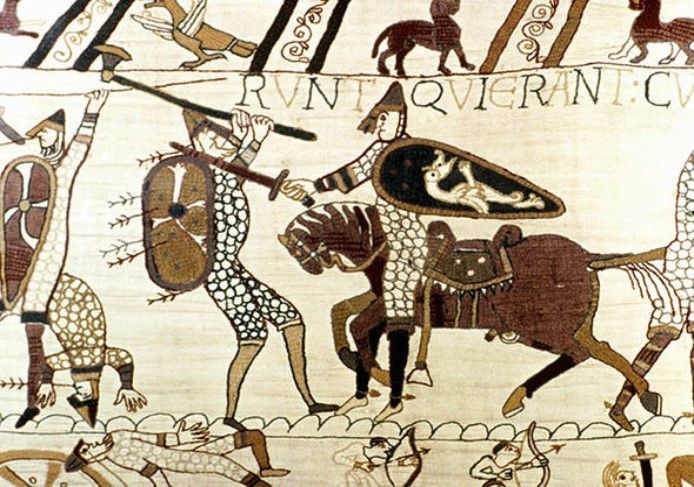

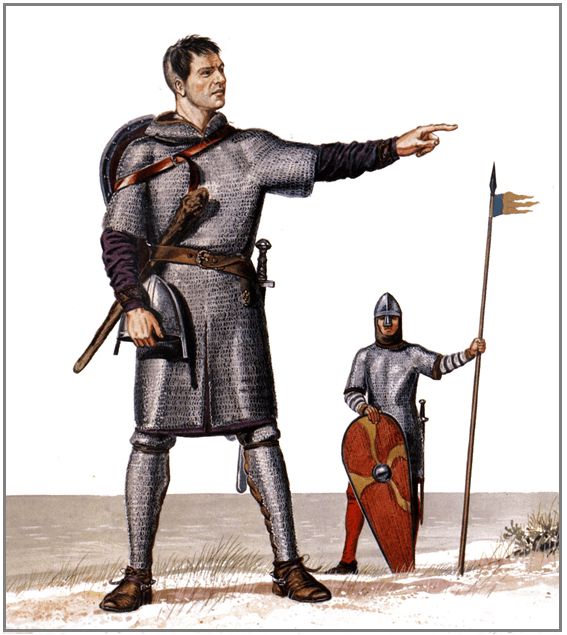

This is Odo, the bishop of Bayeux, in Normandy, the half-brother of Duke William, at the battle of Hastings. Apparently, as an ecclesiastic, he felt unable to wield a sword or spear, like other Normans, and so he has armed himself with what might be thought of (although not by its victims) as a more “peaceable” weapon.

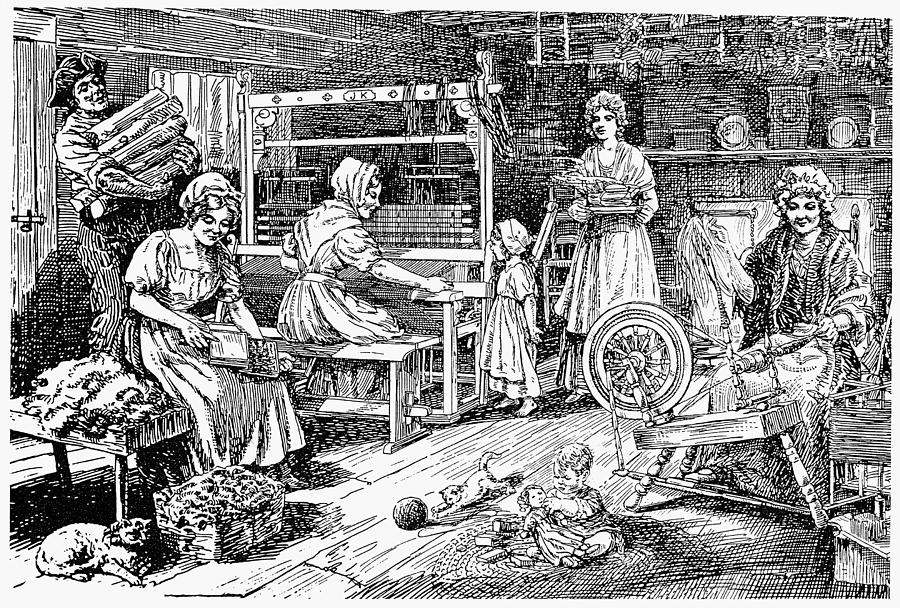

But this is, shall we say, unusual, and there were a wide variety of types to choose from—here’s a selection, along with other medieval weapons–

(by the Funckens, Liliane and Fred, from a very lively 3-volume set on medieval and Renaissance clothing, armor, and weaponry)

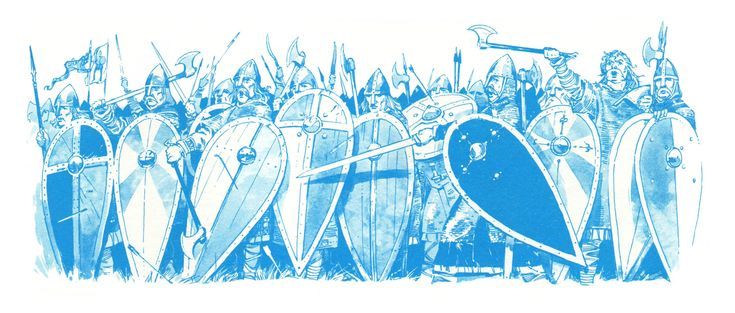

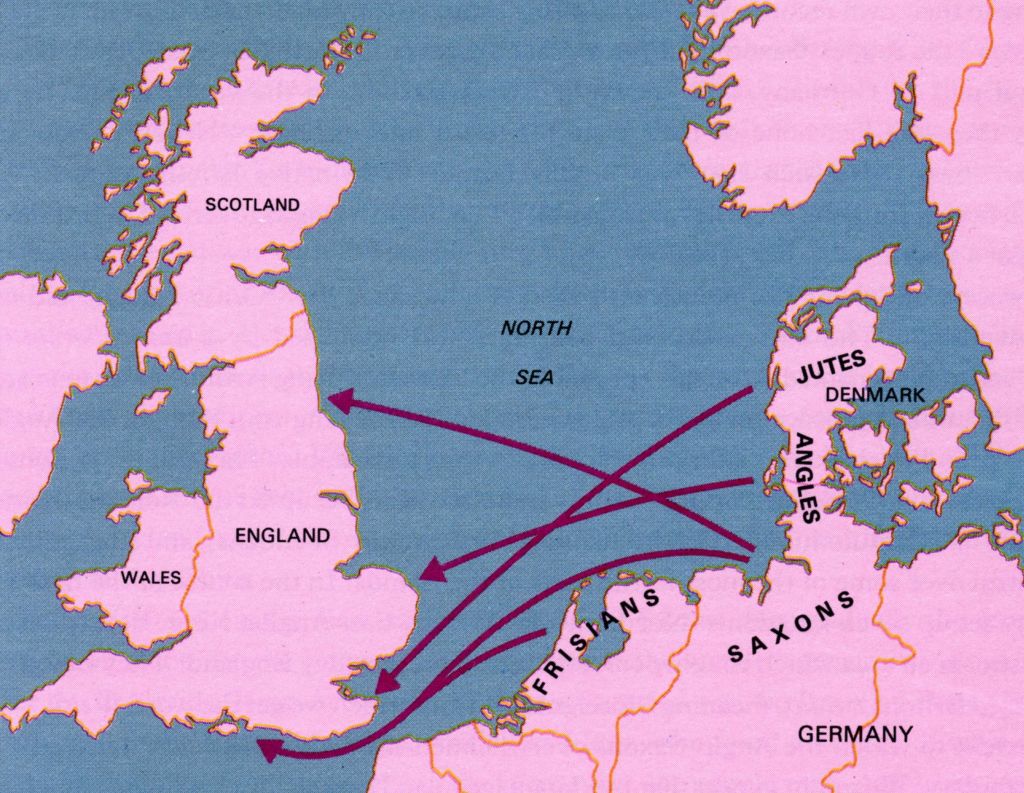

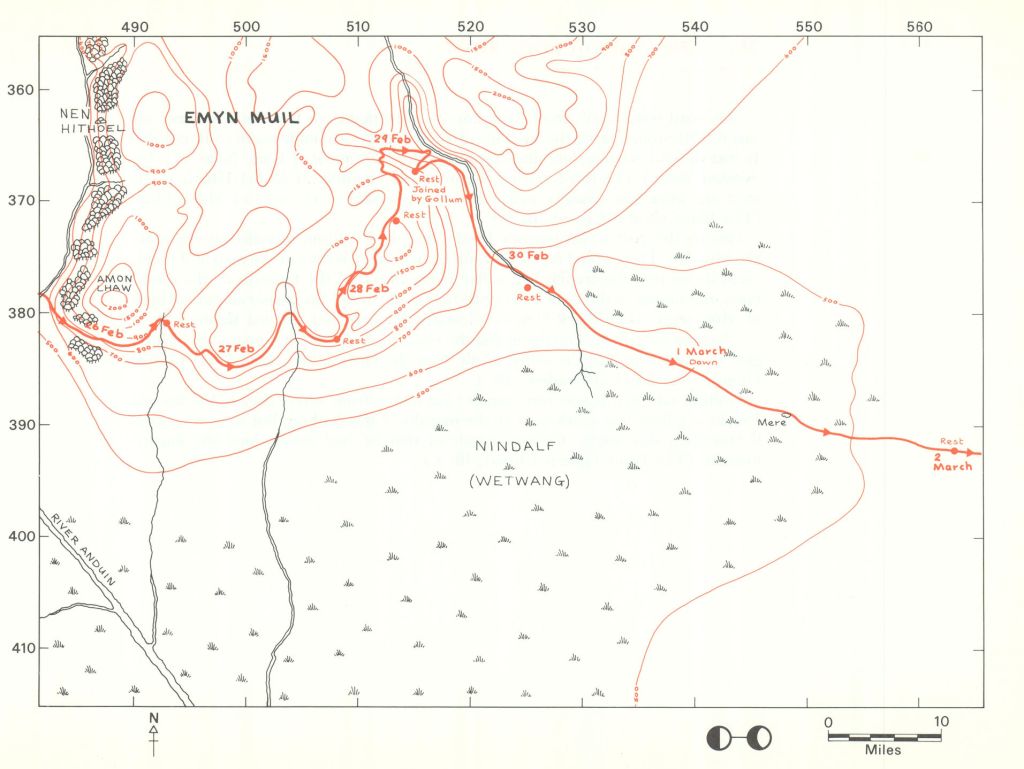

Various artists have made different choices, modeling their work on actual maces, or spinning off into fantasy, but perhaps we can do what Tolkien did with the Rohirrim, when he suggested that their armor would look like the mail of the Normans in the Bayeux Tapestry. (see letter to Rhona Beare, 14 October, 1958, Letters, 401). I haven’t spotted a Norman actually using a mace, but there appears to be an image of one here, between the charging Normans and the defending Anglo-Saxons, on the left (thrown by one of the latter?)–

It’s a bit small for Tolkien’s description, but, blow it up a bit for scale (after all, the Nazgul towers over Eowyn) and perhaps the one labeled “German 16” below would be a rough match?

Ironically, it’s Merry’s ancient sword which saves Eowyn, but, before that, that mace, combined with the force of the Nazgul’s swing, smashes Eowyn’s shield (probably made of overlapping layers of wood, perhaps with a metal covering?) and would have smashed her as well, reminding me of a remark supposedly made by the early 20th-century US President, Theodore Roosevelt, “Speak softly—and carry a big stick”!

Thanks, for reading, as always.

Stay well,

Dare I say stick around

Because, as always, there’s

MTCIDC?

O