Welcome, dear readers, as always.

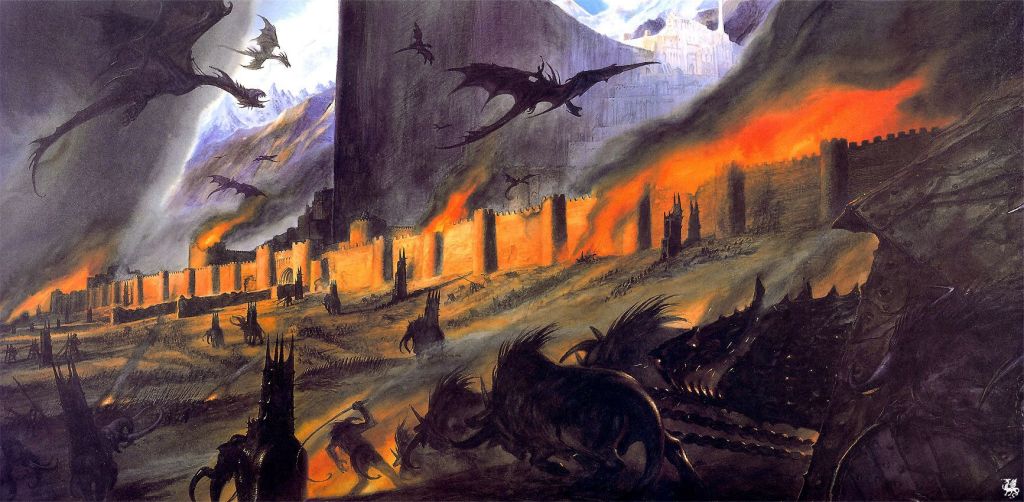

It’s a grim moment, late in The Lord of the Rings. Although Sauron’s forces have failed in their attempt to take Minas Tirith,

(John Howe)

they are still active and numerous, but concealed behind the barrier of the Ephel Duath, the “Mountains of Shadow”, to the east, in Mordor.

(a much-redrawn map, beginning with JRRT. For more details, see: https://tolkiengateway.net/w/index.php?title=Map_of_Rohan,_Gondor,_and_Mordor§ion=2 )

Gondor’s pretend embassy rides out, hoping to keep Sauron’s eye upon them.

(from the Jackson film)

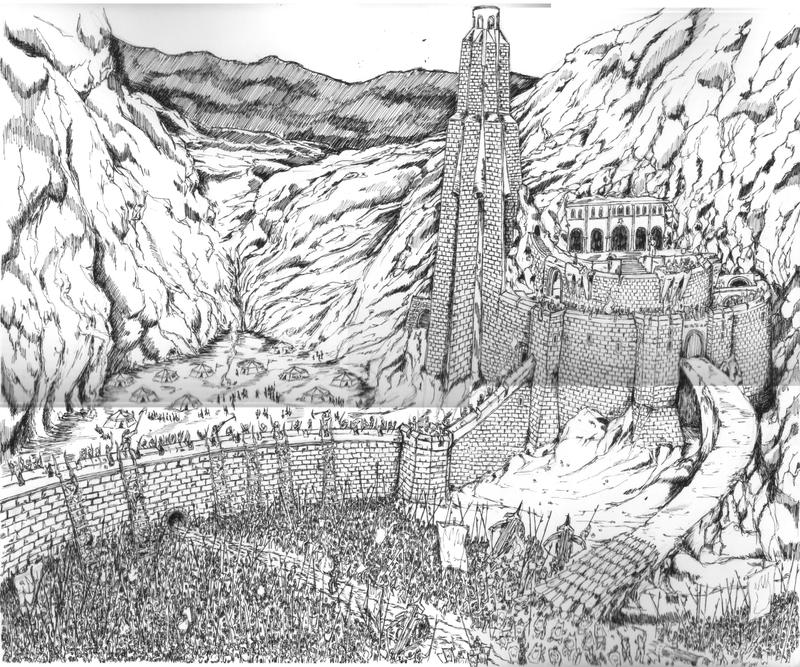

As they approach the Black Gate,

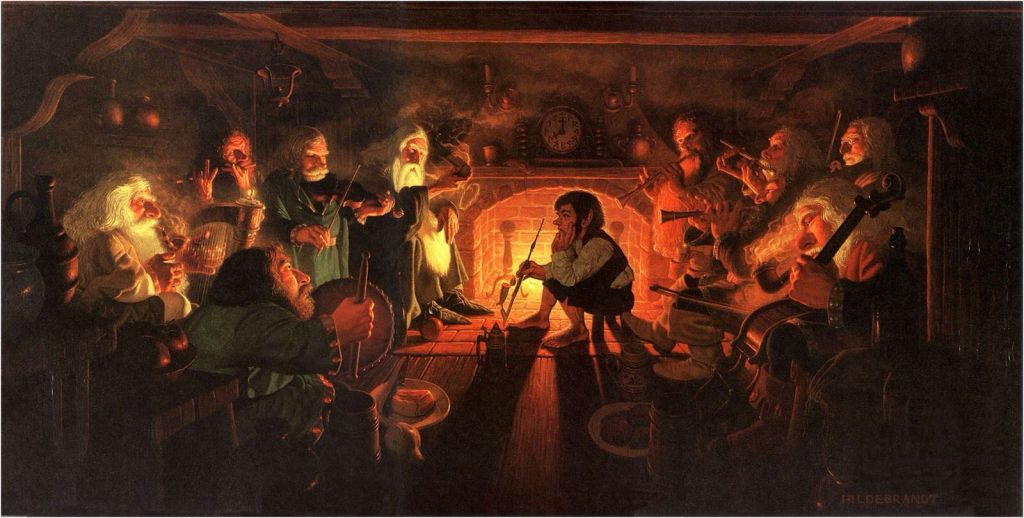

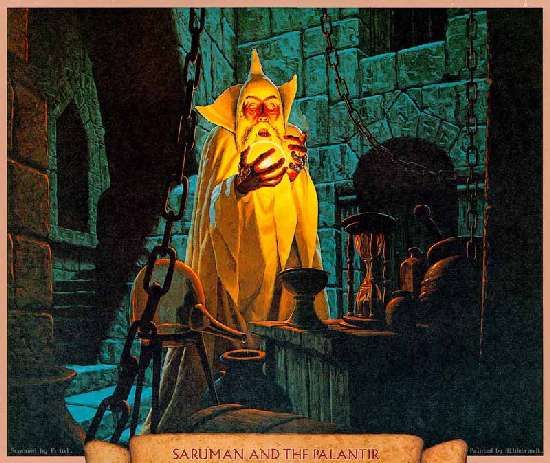

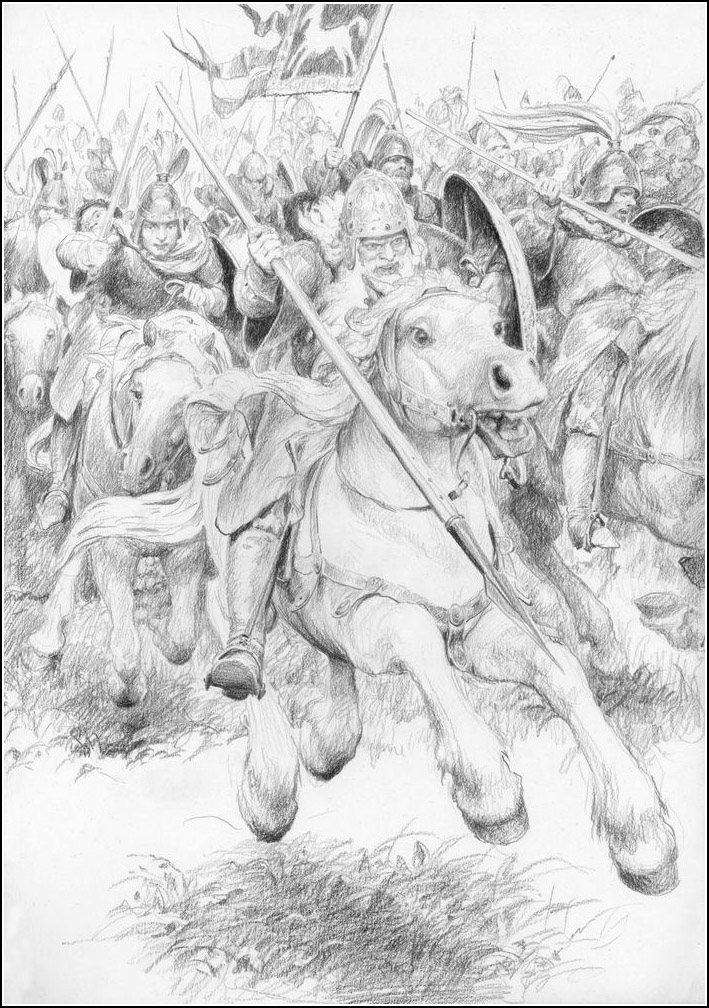

(the Hildebrandts)

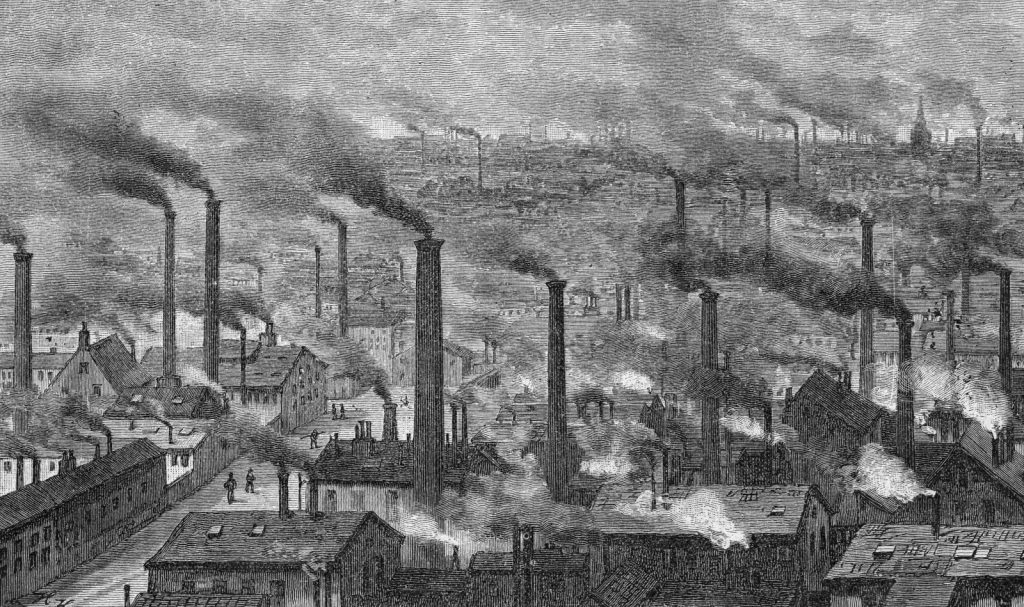

they ride through the effects of the Industrial Revolution which JRRT so disliked:

“North amid their noisome pits lay the first of the great heaps and hills of slag and broken rock and blasted earth, the vomit of the maggot-folk of Mordor…” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 10, “The Black Gate Opens”)

If we hadn’t known previously about Tolkien’s opinion of such, language choices like “vomit” and “maggot-folk”, would have told us all we needed to know and, in this posting, I want to talk a little about a particular form of language, that of diplomacy, in the scene which follows.

The embassy waits before the Black Gate in “a great mire of reeking mud and foul-smelling pools” until, in a carefully-prepared entry, Sauron’s emissary appears:

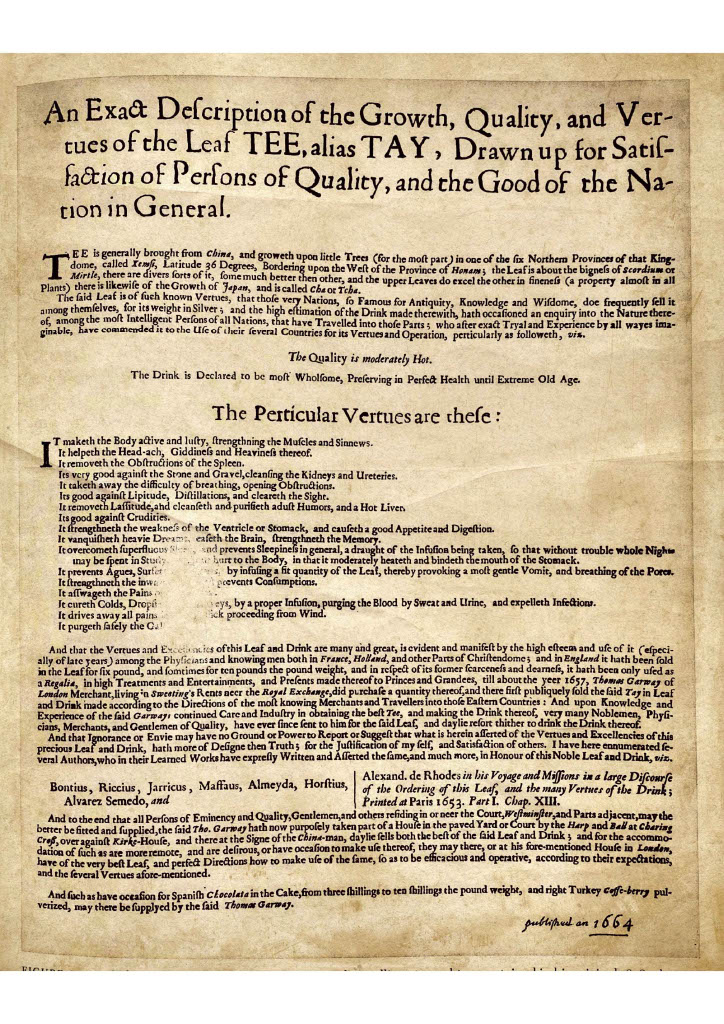

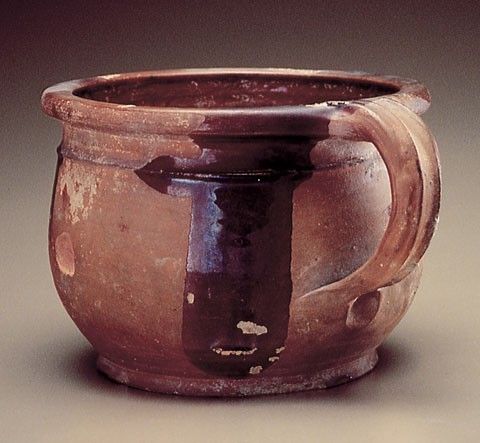

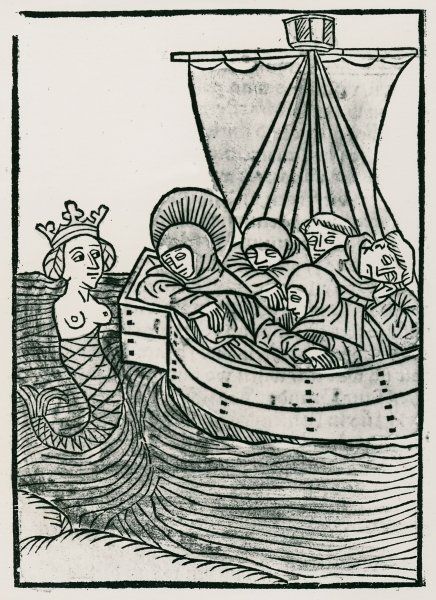

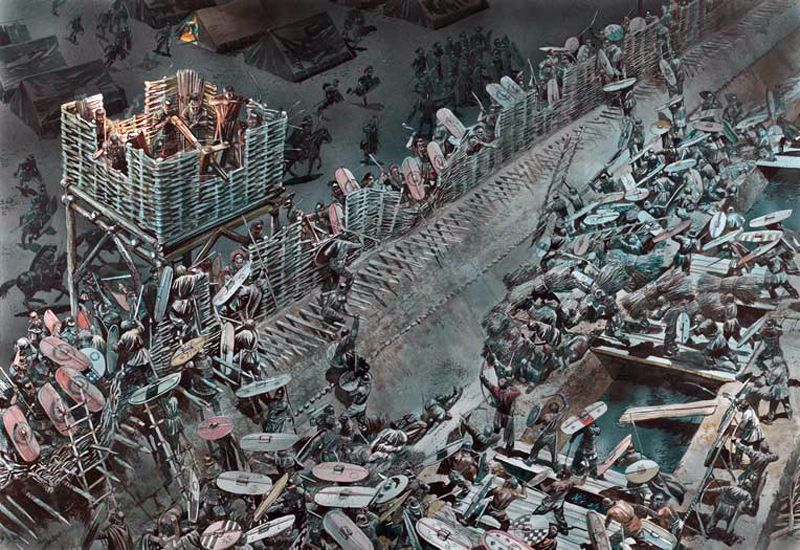

“There came a long rolling of great drums like thunder in the mountains, and then the braying of horns that shook the very stones and stunned men’s ears. And thereupon the door of the Black Gate [that is to say a wicket gate: a smaller gate within a larger one, like this—

although clearly larger than this one] was thrown open with a great clang, and out of it there came an embassy from the Dark Tower.

At its head there rode a tall and evil shape…”

(Douglas Beekman—you can read more about this extremely productive sf/fantasy illustrator here: https://www.askart.com/artist/Doug_L_Beekman/122294/Doug_L_Beekman.aspx )

The emissary—“the Mouth of Sauron”—speaks first and we see already the approach he takes:

“Is there anyone in this rout with authority to treat with me?”

Already he has turned representatives of Gondor into nothing more than an armed mob—a “rout”.

He continues:

“Or indeed with wit to understand me?”

Not only a mob, then, but a stupid one.

Then, turning to Aragorn—

“It needs more to make a king than a piece of Elvish glass, or a rabble such as this. Why, any brigand of the hills can show as good a following.”

And you can see the general idea—

1. this isn’t an army, but a collection of nobodies—and a small one, at that

2. they are nothing but oafs

3. their leader is nothing more than a bandit chief who has appointed himself king

Gandalf then upbraids him:

“It is also the custom for ambassadors to use less insolence. But no one has threatened you.”

To which the Mouth replies:

“So…Then thou arr the spokesman, old graybeard? Have we not heard of thee at whiles, and of thy wanderings, ever hatching plots and mischief at a safe distance?”

First, there’s the implication that Gandalf is a doddering old man, then that he’s a plotter and of no certain abode, and then that he’s a coward. It’s also important to notice the linguistic difference in his and Gandalf’s speech. Unlike certain other Indo-European languages, including German, French and Italian, Modern English has abandoned the second person singular of verbs—no “thou/thy/thee”. It’s “you” for everything. The use of the second person singular is still preserved in those other languages and, at least in traditional French, is reserved for speaking to children, pets, loved ones, and close friends, (and, in older days, servants), there even being verbs, tutoyer, “to use thou” and vouvoyer, “ to use you”, to indicate which you might employ. When uncertain, a person might ask, “On peut tutoyer?”—“Can we use thou?” The advantage it provides, as we can see here, is that, whereas Gandalf is being polite, or at least neutral, the Mouth of Sauron is being intentionally insulting—the old expression being “too familiar”—or at least downgrading Gandalf from an equal to someone of lower status, or even a child, which goes along with his earlier question as to whether anyone had the understanding (“wit”) to have a discussion with him.

The Mouth then shows Frodo’s gear, taken from him in Minas Morgul, and Pippin, recognizing it, “sprang forward with a cry of grief”, even as Gandalf tries to stop him, which gives the Mouth another opportunity:

“So you have yet another of these imps with you!…What use you find in them I cannot guess; but to send them as spies into Mordor is beyond even your accustomed folly. Still, I thank him, for it is plain that this brat at least has seen these tokens before, and it would be vain for you to deny them now.”

Not content with downgrading the Gondorians, Aragorn, and Gandalf, hobbits are now either “imps”—that is, small demons, as in “imps of Satan” in our Middle-earth, or children, “brats”. He then goes on to call the Shire “the little rat-land” as he builds what he claims the so-far successful resistance to Sauron actually is:

“Dwarf-coat, elf-cloak, blade of the downfallen West, and spy from the little rat-land of the Shire—nay, do not start! We know it well—here are the marks of a conspiracy.”

Now we see where all of this is leading: to Sauron’s terms—which are not about a cease-fire or a deal between equals, but simply a form of surrender:

“The rabble of Gondor and its deluded allies shall withdraw at once beyond the Anduin, first taking oaths never again to assail Sauron the Great in arms, open or secret.”

This repeats the Mouth’s earlier characterizing of the emissaries from Gondor as a mob—and the suggestion that they are nothing more than a group of plotters against Sauron’s (legitimate) authority.

“All lands east of the Anduin shall be Sauron’s for ever solely.”

His earlier struggles with the West had led to his defeat and loss of control of those lands, so here Sauron is attempting to guarantee that they stay in his hands this time.

“West of the Anduin as far as the Misty Mountains and the Gap of Rohan shall be tributaries to Mordor, and men there shall bear no weapons, but shall have leave to govern their affairs.”

Here we see the Rohirrim being:

a. disarmed

b. forced to pay tribute

“But they shall help to rebuild Isengard which they have wantonly destroyed…”

“wantonly” suggests, of course, that it was done without purpose—and, remembering what Saruman was actually up to, this is actually laughable, but it’s also a piece with the general tone: we are the legitimate authorities, you have plotted against us and rebelled and with no good reason.

And then we see what the Mouth has in mind for himself:

“…and that shall be Sauron’s and there his lieutenant shall dwell: not Saruman, but one more worthy of trust.”

(“Looking in the Messenger’s eyes they read his thought: He was to be that lieutenant, and gather all that remained of the West under his sway; he would be their tyrant and they his slaves.”)

So far, all of this has been demands on Sauron’s part, but what will he give in return?

“It seemed then to Gandalf, intent, watching him as a man engaged in fencing with a deadly foe, that for the taking of a breath, the Messenger was at a loss; yet swiftly he laughed again,

‘Do not bandy words in your insolence with the Mouth of Sauron!…Surety you crave! Sauron gives none. If you sue for his clemency, you must first do his bidding. These are his terms. Take them or leave them.’ “

Putting all of this together, we see that, unlike the “custom of ambassadors” of Gandalf, this is a carefully-planned verbal attack, first denigrating the other side’s position for negotiating, then suggesting that, unlike an opposing state, the Gondorians are nothing more than illegimate plotters, then making a series of demands for which they are offered nothing in return except possible “clemency”.

This, then, is not a treaty—none is offered—but the treatment of rebellious slaves and well deserves Gandalf’s rebuke which, you’ll notice, returns some of the Mouth’s medicine to him, even if not using “thou”:

“But as for your terms, we reject them utterly. Get you gone, for your embassy is over and death is near to you. We did not come here to waste words in treating with Sauron, faithless and accursed; still less with one of his slaves. Begone!”

Is the Mouth’s reaction surprising, then?

“Then the Messenger of Mordor laughed no more. His face was twisted with amazement and anger to the likeness of some wild beast that, as it crouches on its prey, is smitten on the muzzle with a stinging rod. [How appropriate for the Mouth!] Rage filled him and his mouth slavered, and shapeless sounds of fury came strangling from his throat. But he looked at the fell faces of the Captains and their deadly eyes, and fear overcame his wrath. He gave a great cry, and turned, leaped upon his steed, and with his company galloped madly back to Cirith Gorgor.”

A fitting end—wordless, he flees—undoubtedly with Gandlaf’s last words in his ears: “…slave. Begone!”

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

Avoid evil emissaries with their own agendas,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O