Tags

Charlemagne, Child Ballads, Childeric III, Merovingian Kingdom, Pepin le Bref, Perry the Platypus, Pippin, pipping, Pope Zachary, The Bayeux Tapestry, Tolkien

Welcome, as always, dear readers.

When I was little, I heard a folksong, “I gave my love a cherry”, with these lines:

“I gave my love a cherry that has no stone

I gave my love a chicken that has no bone

I gave my love a ring that has no end

I gave my love a baby with no cryen

How can there be a cherry that has no stone?

How can there be a chicken that has no bone?

How can there be a ring that has no end?

How can there be a baby with no cryen?

A cherry, when it’s blooming, it has no stone

A chicken when it’s pipping, it has no bone

A ring when it’s rolling, it has no end

A baby when it’s sleeping, has no cryen.”

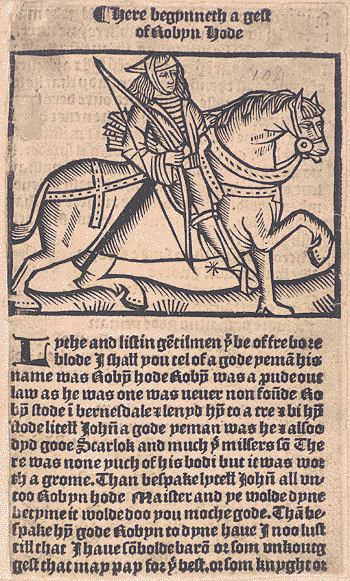

Now, I know that it belongs to a riddle song tradition seen in two Child Ballads: “Riddles Wisely Expounded” (#1) and “Captain Wedderburn’s Courtship” (#46), as well as in several supposedly-impossible task ballads, including “The Elfin Knight” (#2), but then it was just puzzling—especially that line about “A chicken when it’s pipping”.

Since then, I have seen two explanations:

1. “pipping” is the chick still developing in the egg

2. “pipping” is the act of the chick breaking out of the egg and its bones have not yet matured

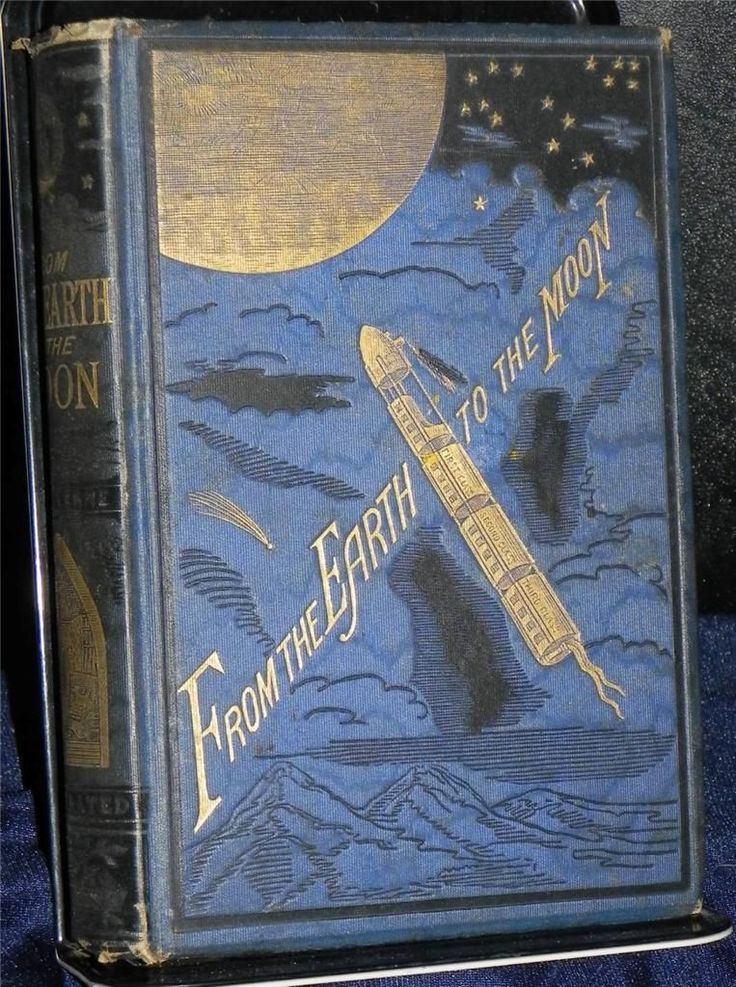

“Pipping” is characteristically sung “pippin’” and that was undoubtedly in my head when I first read The Lord of the Rings, and there was “Pippin”—Peregrine Took.

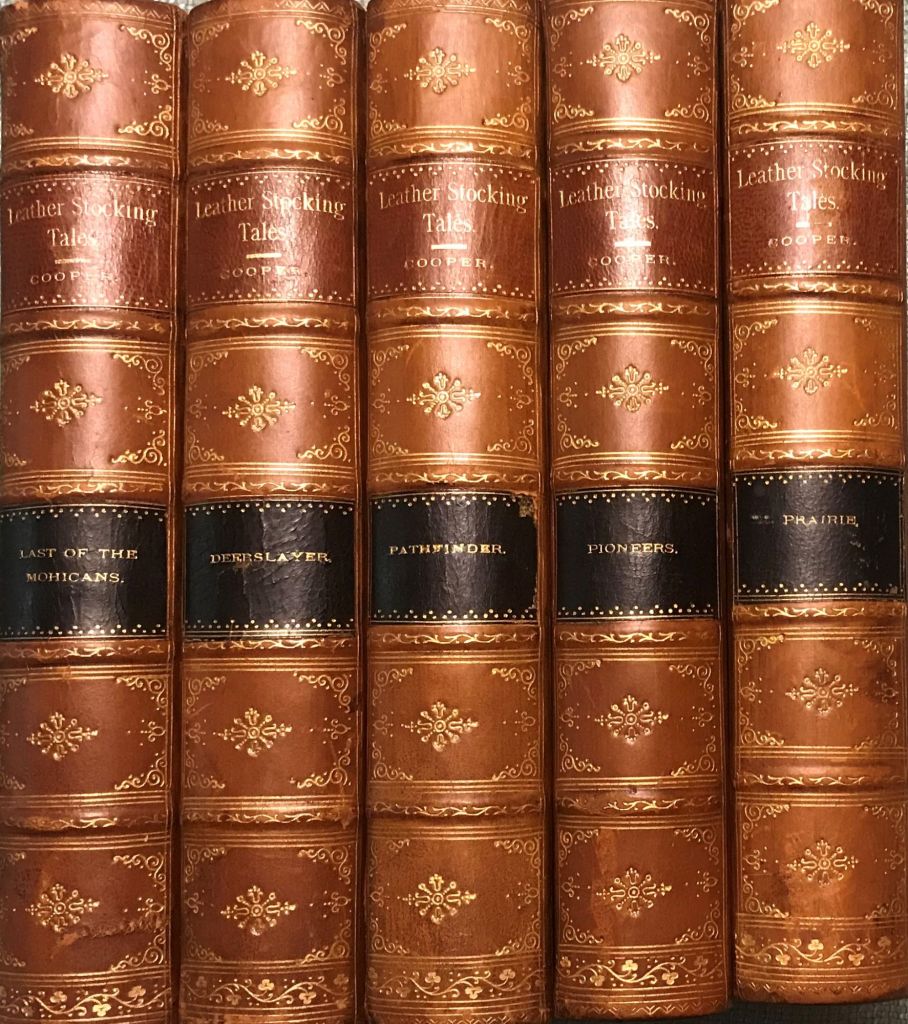

Took is a Norman-English family name, the first member in England being one of the invaders in 1066,

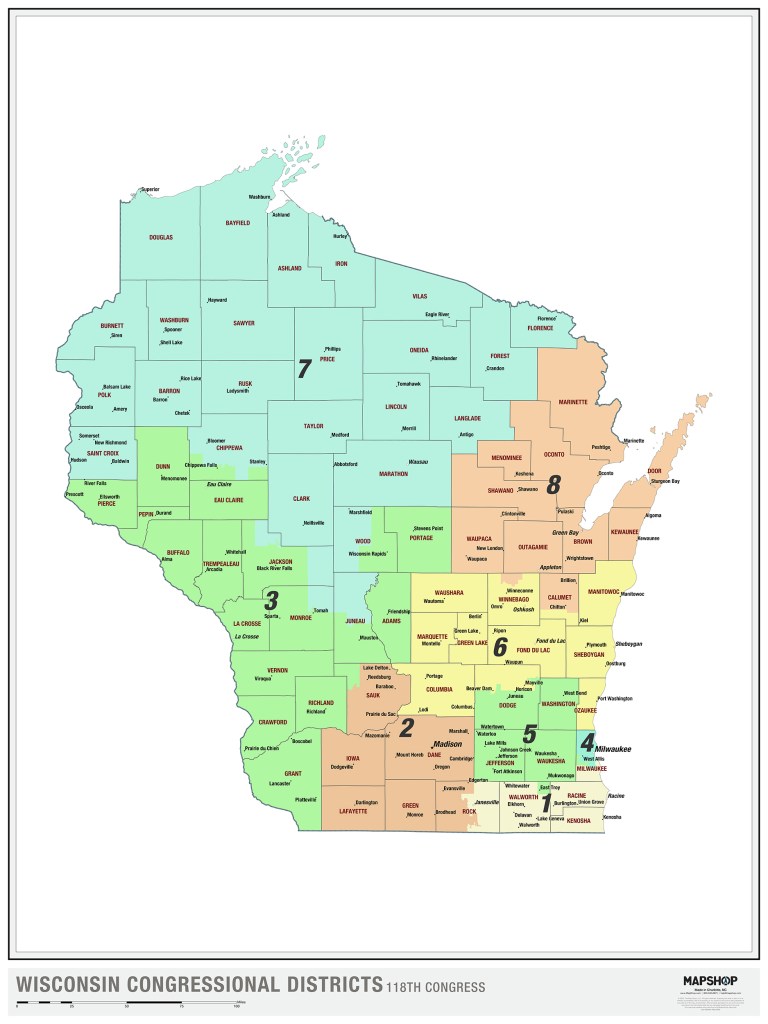

mentioned in (Robert? his first name is under discussion—sometimes he’s just called “Master”) Wace’s 12th century verse chronicle Roman de Rou (the “story of Rollo”—that is, of Hrolfr, a Viking colonizer of the western coast of France who became a vassal of the French king, Charles III (“ the Simple”), under the name “Rollo”, controlling what would become Normandy—“Norsemanland”—for more, see: https://vikingr.org/explorers/rollo )

(from his tomb in Rouen Cathedral—a medieval idea of his appearance–and they wouldn’t have had much to go on as the tomb has been despoiled more than once: report has it that only one femur remains inside)

which includes material about the conquest of England and where the sire “de Touques” (Touques is a town and river in Normandy—see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Touques,_Calvados ) appears (see Master Wace, his chronicle of the Norman Conquest from the Roman de Rou, translated and edited by Edgar Taylor, 1837, where you can see the name on page 212: https://archive.org/details/masterwacehischr00waceuoft/page/210/mode/2up )

“Peregrine” is Latin peregrinus, formed from peregre, literally “through the fields” (per agros), meaning “coming from somewhere else”, hence “foreign(er)/strang(er)/and, eventually, “pilgrim”. See for more: https://www.etymonline.com/word/pilgrim I suspect that the name was inspired by Tolkien’s religious background, where there are several saints with that name:

1. a 2nd-century AD martyr (you can read about him here: https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=5564 )

2. a 7th-century Celtic figure (you can read about him here: https://www.saintforaminute.com/saints/saint_peregrinus_of_modena )

3. a 13th-century Italian (you can read about him here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peregrine_Laziosi )

“Pippin”, however, appears to be a bit murkier. One would assume that the nickname for Peregrine would be “Perry” (as in Perry the Platypus from the wonderful animated series “Phineas and Ferb”—for more see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phineas_and_Ferb ).

So where does Pippin come from?

I go back to what so often I find helpful for JRRT: the Middle Ages.

And here I find Latin “Pipinus”, who could be this colorful character, Pepin (nicknamed “Shorty”—le Bref), c.714-768, the 8th-century Mayor of the Palace (chief officer under the king)

(to the right is Pepin’s father, Mayor of the Palace before him, Charles “Martel”–“the Hammer”)

in Merovingian Francia (for more on this, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merovingian_dynasty .

Pepin is known in history for two things:

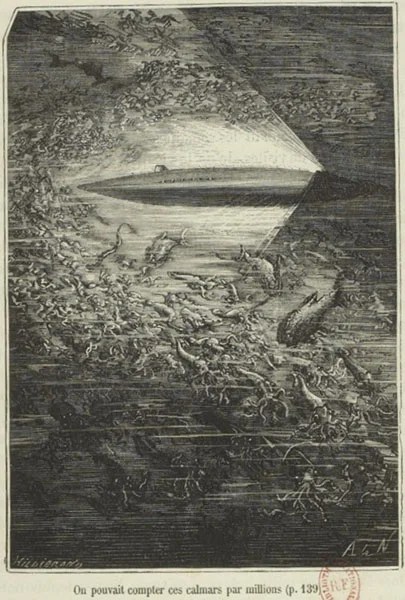

1. with the blessing of Pope Zachary, in 751, he overthrew the Merovingian king, Childeric III, ending the dynasty and making himself king

2. he was the father of Charlemagne, 747-814, creator of the short-lived Carolingian Empire (800-843)

(As always, coins have so much to tell us beyond their monetary significance. This is a good example of using a Roman model to suggest that, somehow, the person depicted is descended from earlier Roman rulers: it’s in Latin and uses Roman imperial titles—“IMP” = “Imperator”, once only “one holding the Senate’s authority outside Rome” but, from the time of Tiberius, 42BC-37AD, used as we use “emperor”; “AUG” = “Augustus”, a title originally given by a subservient Senate to Octavian, the heir to his greatuncle, Julius Caesar, and, after 30BC, owner of the whole Mediterranean basin. As well, Charlemagne is wearing just the suggesting of later Roman armor, covered by a Roman military cloak and, on his head, is the early—and modest—imperial crown—a victor’s wreath. Charlemagne’s ancestors were the Franks, Germanic invaders who would give France its name. Charlemagne’s name is the Latin form, “Carolus”, of a Germanic name, “Karl” and note how it’s spelled in the Latin inscription: “Karolus”. Latin doesn’t use the letter K—so, a Germanic practice?)

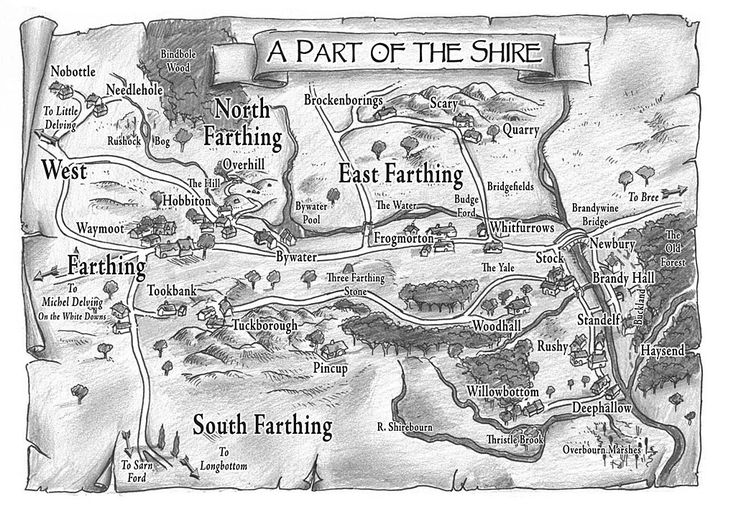

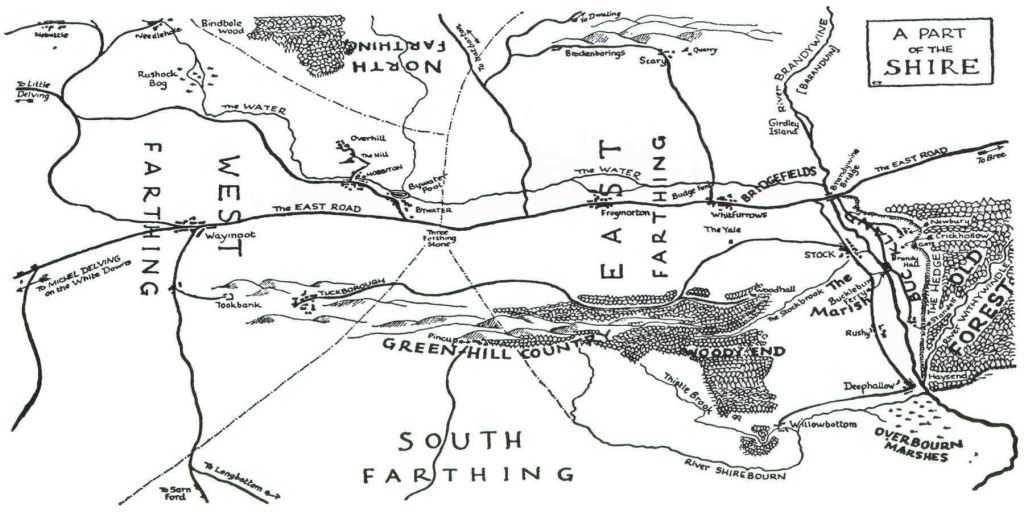

As Drogo and Freddie are out of the medieval Germanic past, I would suggest that, whereas Took is Anglo-Norman and Peregrine is Latin, Pippin may have gotten his nickname from a similar source, a fittingly distinguished name for someone who, after the War of the Ring, would become Thain of the Shire, Knight of Gondor, and Counsellor of the North Kingdom.

Thanks for reading, as always.

Stay well,

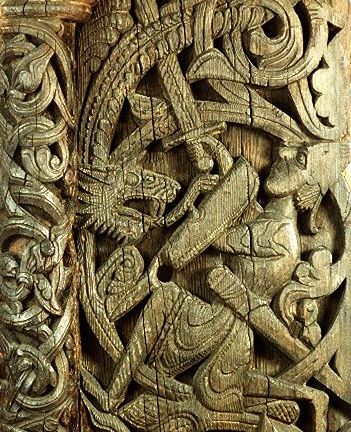

Dark Ages? What Dark Ages? You just have to know where to look—Tolkien did,

And remember that there’s always

MTCIDC

O