Tags

Beowulf, Bilbo, Cirdan, Dorothy, Fantasy, Gandalf, Herakles, Kansas, King Arthur, lotr, Mulan, Narya, Rings of Power, Superman, The Grey Havens, The Hobbit, The Rings of Power, Tolkien, tornado, Valar

As always, dear readers, welcome.

In adventure stories, heroes—and heroines– seem to appear in all sorts of ways.

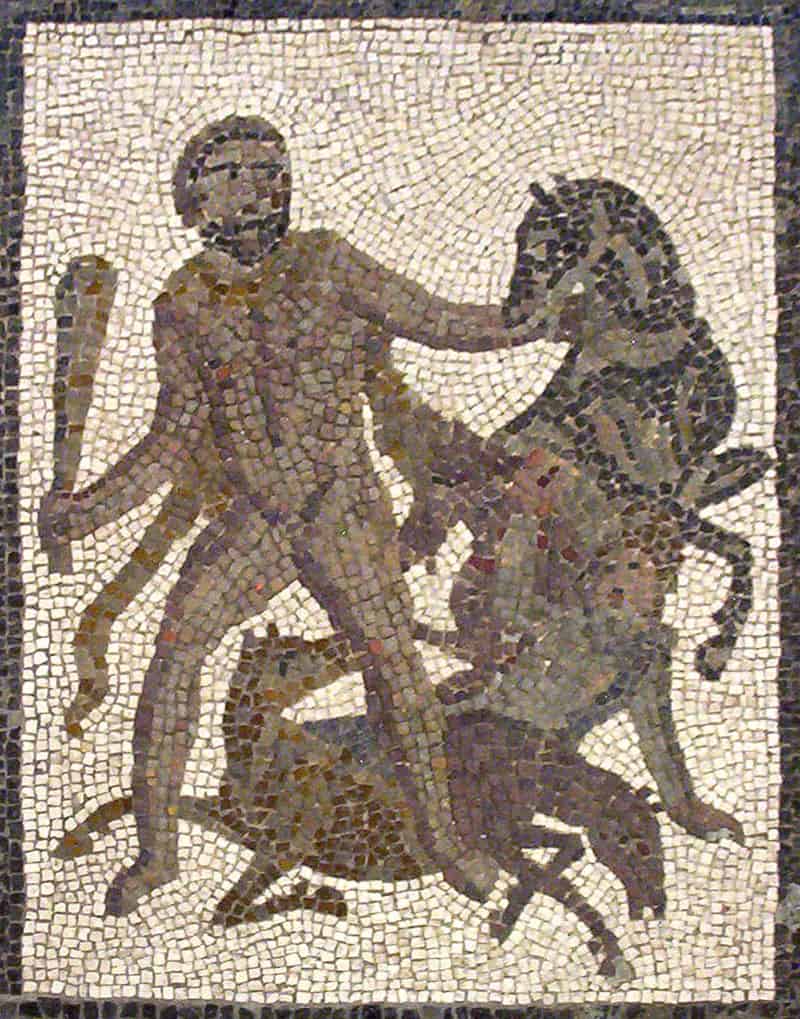

Sometimes, it seems that they are just born for adventure, like Herakles, who,

although apparently the offspring of two mortals, Alkmene and Amphitryon, was actually the son of Zeus.

Others belong to noble families, where heroism is expected of them, like Beowulf, nephew of the king of the Geats.

(Here, meeting the Danish coastguard—but we just can’t escape those Wagnerian winged helmets, can we?)

Then there is Mulan, who, pretending to be a man, replaces her father in the army and serves valiantly for twelve years.

(As you can see from the label, this comes from a site called “Chinese Posters.net”—and it’s quite a site: 5100 propaganda posters from the Chinese past. Here’s the address: https://chineseposters.net/ For more on the original but probably fictional Mulan, see: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1596/mulan-the-legend-through-history/ and https://mulanbook.com/pages/northern-wei/ballad-of-mulan/ and https://en.m.wikisource.org/wiki/Translation:Ballad_of_Mulan –two versions of the early “Ballad of Mulan)

A common motif is that of the apparent good-for-nothing—or at least for not much—who turns out to be of heroic material. I immediately think of King Arthur, who is, basically, a servant until he fetches that sword from the stone/anvil.

Heroes and heroines, then, can be anything from a demigod to a nobleman to a good girl who loves her father to a good-for-nothing who is more than he seems, and set out on adventures or, as in the case of Arthur, adventure finds them.

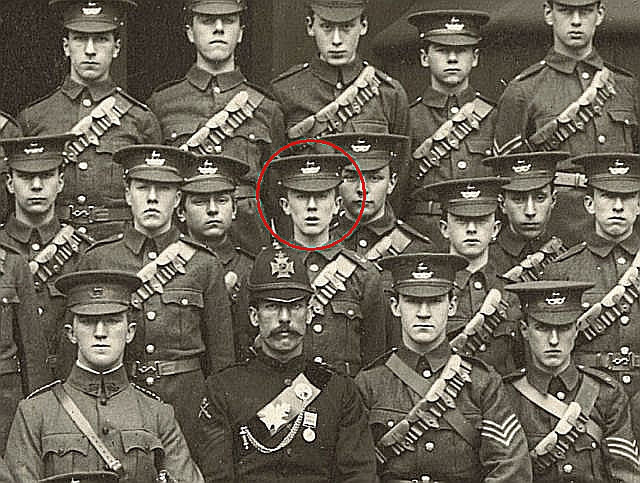

Ordinary—or seemingly ordinary—people can also be pulled into adventures, as Bilbo is.

(the Hildebrandts)

Then there are people who are literally dropped into adventures,

(WW Denslow)

sometimes beginning those adventures in a very dramatic—and ultimately decisive—way.

Dorothy, of course, has been whirled by a tornado from Kansas to Oz,

(from the 1939 film)

but, when she arrives in Oz in the film, Glinda, the Good Witch of the North

(also from the film)

sings:

“Come out, come out, wherever you are and meet the young lady

Who fell from a star.

She fell from the sky, she fell very far and Kansas, she says,

Is the name of that star.”

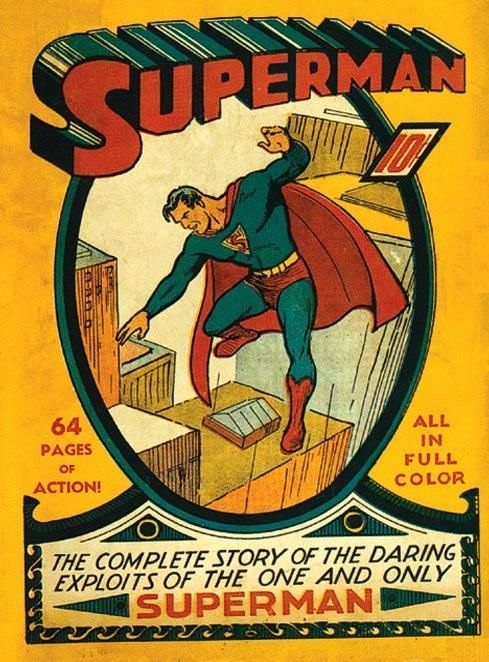

Not true, of course, of Dorothy, (although Kansas has its beauties, no doubt), but it is true of another hero, Superman,

who had been shipped in a rocket by his parents from the dying planet, Krypton, and discovered in a field by Ma and Pa Kent, who would become his foster parents.

If you read this blog regularly, you know that I don’t find negative reviews which are nothing but hatchet jobs

at all helpful and, in my own reviews, I try to understand what it is that the creators attempted to do and react to that, being aware, of course, that I do have my own perspective on things. I also buy DVDs of everything I can, so that I can watch things more than once before I review.

I’ve now seen “Rings of Power”, both seasons,

only once, so I’m not going to attempt to review the whole two seasons here. Certainly there have been some very impressive visuals and some very good acting. I’m not sure how I feel about the two as a whole—some of the plot I found rather confusing and I’m not sure how I feel about proto-hobbits with Irish accents, although the idea of using proto-hobbits was, I thought, pretty ingenious—but I want to end this posting by talking about Gandalf.

He first appears—like Dorothy in Oz, but even more so like the baby Superman, in a dramatic fashion, having been conveyed in which appears to be a kind of meteor which roars across the sky and slams into the earth, leaving a fiery crater.

(Thank goodness that, whoever sent him, dressed him in underpants so that he wouldn’t embarrass himself or us when he stood up.)

At first, he seems stricken and quite clueless, not even really having language at first, although certainly having great powers, and it takes two seasons for him to begin to understand himself and what he’s been sent to do and I suspect that this stricken quality comes from a hint in Christopher/JRR Tolkien’s Unfinished Tales, where, under “The Istari” we find:

“For it is said indeed that being embodied the Istari had need to learn much anew by slow experience…” (Unfinished Tales, 407)

I understand that the creators of the series were somewhat hampered in their work—should they want to be as faithful as possible to Tolkien—because they were restricted in their sources, being confined, in this case, to The Lord of the Rings and its appendices. And, at first glance, the appearance in Middle-earth of the Istari does seem rather vague.

In Appendix B, “The Third Age”, of The Lord of the Rings, we read:

“When maybe a thousand years had passed, and the first shadow had fallen on Greenwood the Great, the Istari or Wizards appeared in Middle-earth. It was afterwards said that they came out of the Far West and were messengers sent to contest the power of Sauron, and to unite all those who had the will to resist him…”

No meteors are mentioned, but no other means of transport, either, yet turn the page and we then read:

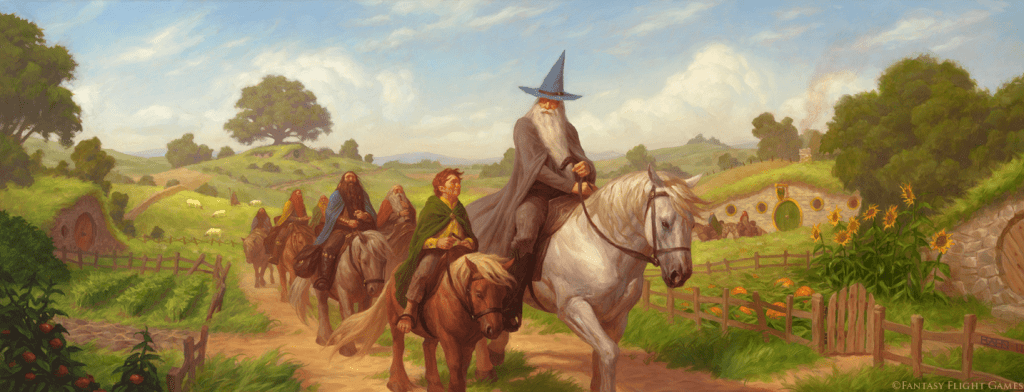

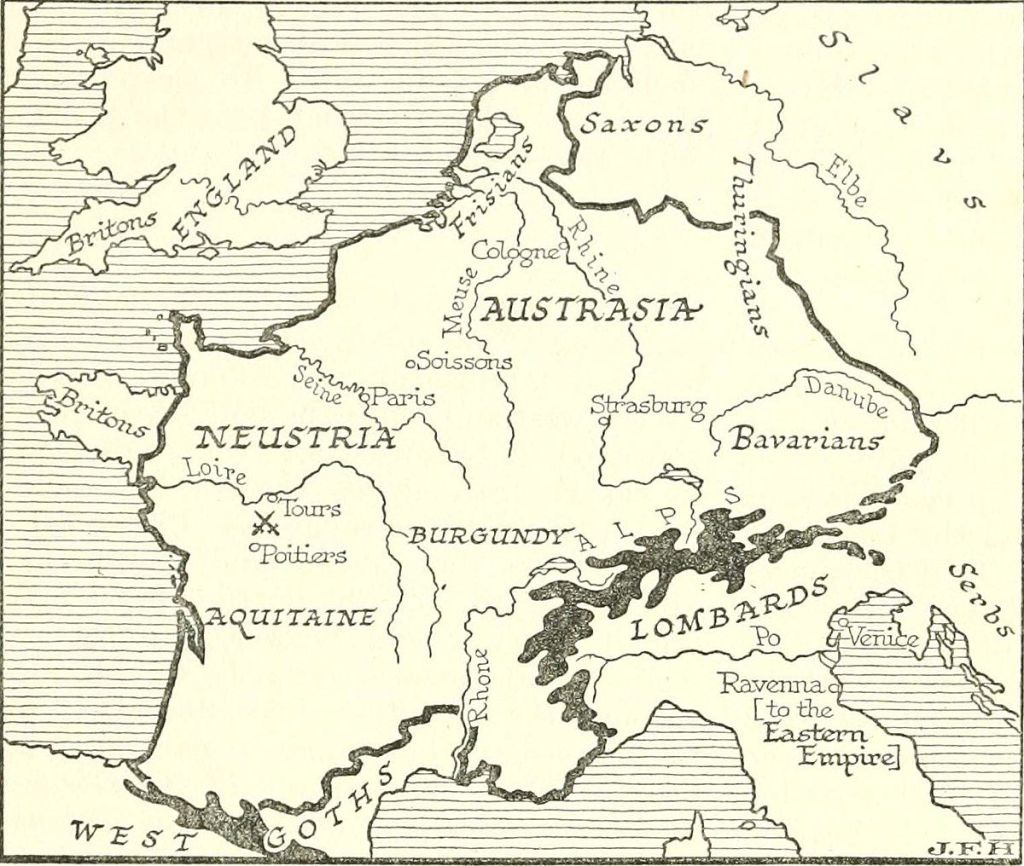

“Gil-galad before he died gave his ring to Elrond; Cirdan later surrendered his to Mithrandir (aka Gandalf). For Cirdan saw further and deeper than any other in Middle-earth, and he welcomed Mithrandir at the Grey Havens, knowing whence he came and wither he would return.”

If you know The Lord of the Rings, you know that the Grey Havens is a seaport on the west coast of Middle-earth: it’s where Gandalf and others, including Frodo, depart for the Uttermost West—that is, Valinor.

(Ted Nasmith and a gorgeous view)

In fact, it was the Valar who had sent the Istari in the first place, as we know from Unfinished Tales, 406:

“For with the consent of Eru they sent members of their own high order, but clad in bodies as of Men, real and not feigned…”

And thus, from the source to which I’m informed the creators were confined, they would have learned that the Istari had sailed to Middle-earth, not been shot across the sky like Dorothy or Superman. Why make such a change, especially as, because Cirdan recognizes Gandalf’s worth, he gives him one of the original Elvish rings, Narya, which turns up on his hand in the subsequent The Lord of the Rings?

The title of this posting is a quotation from Shakespeare, from the prologue to “An EXCELLENT conceited Tragedie OF Romeo and Juliet” (as the First Quarto title page reads) in which the Prologue says of the protagonists: “A paire of starre-crost Louers tooke their life”.

The creators of The Rings of Power, even with evidence available to them, have veered away from that evidence with no explanation as to why they have made such a choice. What else may they have chosen to change and how might that affect JRRT’s view of the earlier history of Middle-earth, as well as ours?

As I begin my second viewing of The Rings of Power, then, I’ll be curious to see if another Shakespeare quotation, this from “The Tragedie of Julius Caesar”, Act 1, Scene 1, when Cassius, the leader of the plot against Julius Caesar, is trying to persuade Brutus to join him, may apply to the creators and their work:

“The fault (deere Brutus) is not in our Starres,

But in our Selues…”

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

Think about what Cassius is telling us about horoscopes,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O