Welcome, as always, dear readers.

Star Wars: the Phantom Menace

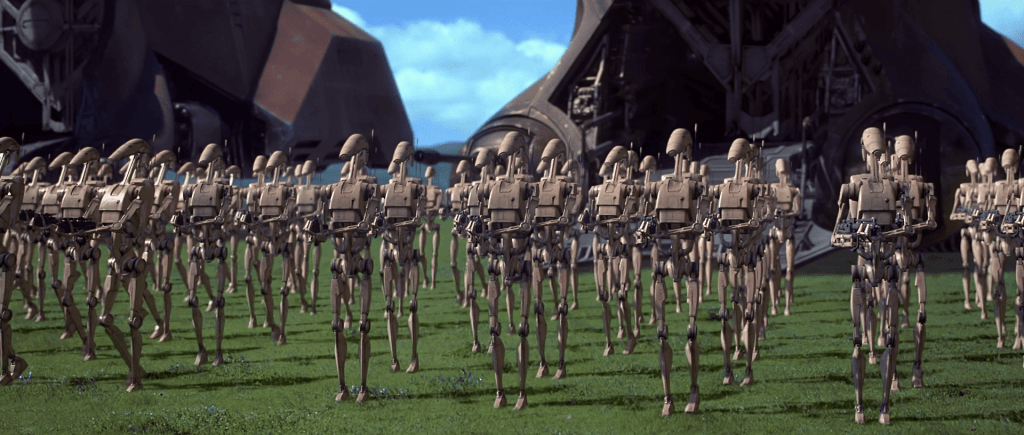

certainly begins with a bang: a Jedi and his padawan, sent on a peace mission to the planet Naboo, are attacked by poisoned gas and droids

(reminding me at once of those lines from Weird Al Jankovic’s song:

“But their response, it didn’t thrill us

They locked the doors and tried to kill us”

If you don’t know “The Saga Begins”, you can watch it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hEcjgJSqSRU )

but escape to the surface only to be almost squashed in an invasion of droid armor

before they rescue an unlikely helper (right out of Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk-Literature B350-B390, “Grateful Animals”),

who takes them to an underwater city where they come before Boss Nass, who blames upperworlders for the invasion

and responds to their warning that, after they finish with the upperworlders, the invaders will be coming for those below the water:

“Dos mackaneeks no comen here. Dey not know of usen.”

The Gungans (which is what these people call themselves) are sophisticated technologically enough to have an underwater city

and self-propelled transport,

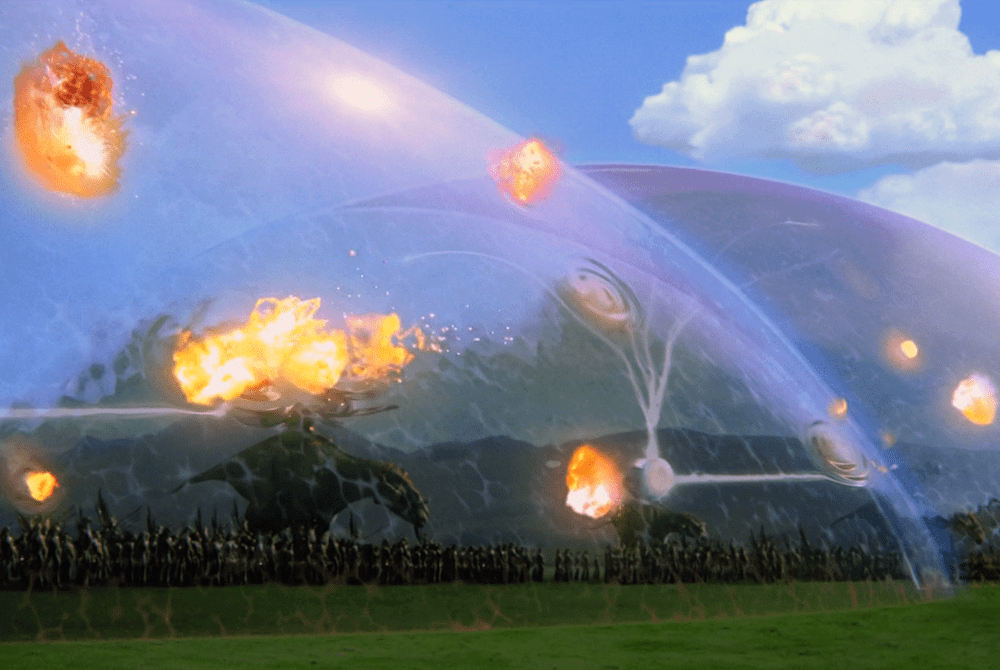

and they even can produce an energy shield,

but faced with the armament of the invading droid army—

and its hordes of infantry,

their use of energy balls (“boomas”)

and shields

which bear a faint resemblance to Celtic shields in some clear material

show them to be really no match for the droids and their technology. Only luck from the outside saves them.

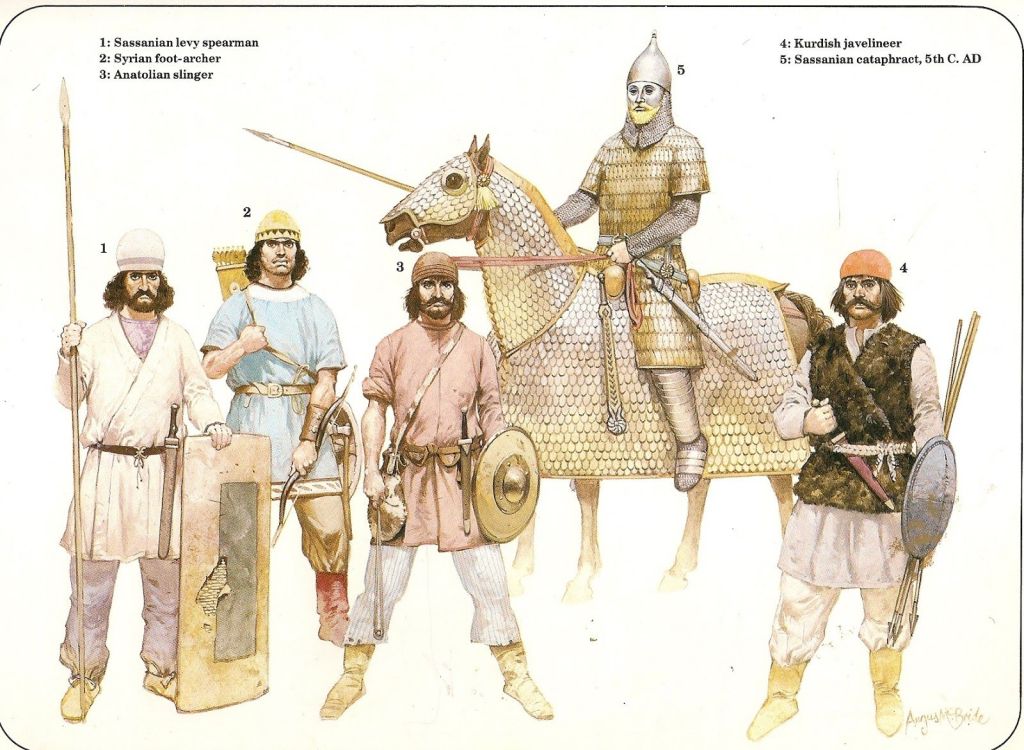

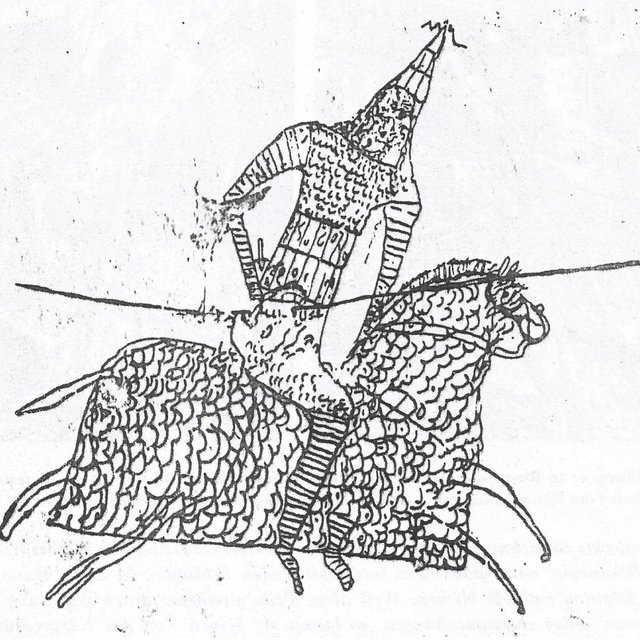

The Gungans are brave and their weapons can cause some damage, but it’s obvious that they’re outclassed technologically, which makes me think of the Aztecs, the center of whose capital, Tenochtitlan, built in the middle of a lake, was a series of sophisticated and elegant stone buildings (complete with an aqueduct),

but who, unfortunately for them, were a late Neolithic culture who, with no metal with which to work, made their weapons using volcanic glass, obsidian, which was sharp,

(this and the next by Angus McBride)

but no match for the conquistadores’ steel weapons, armor, and early firearms.

And this brings me to a “what if”.

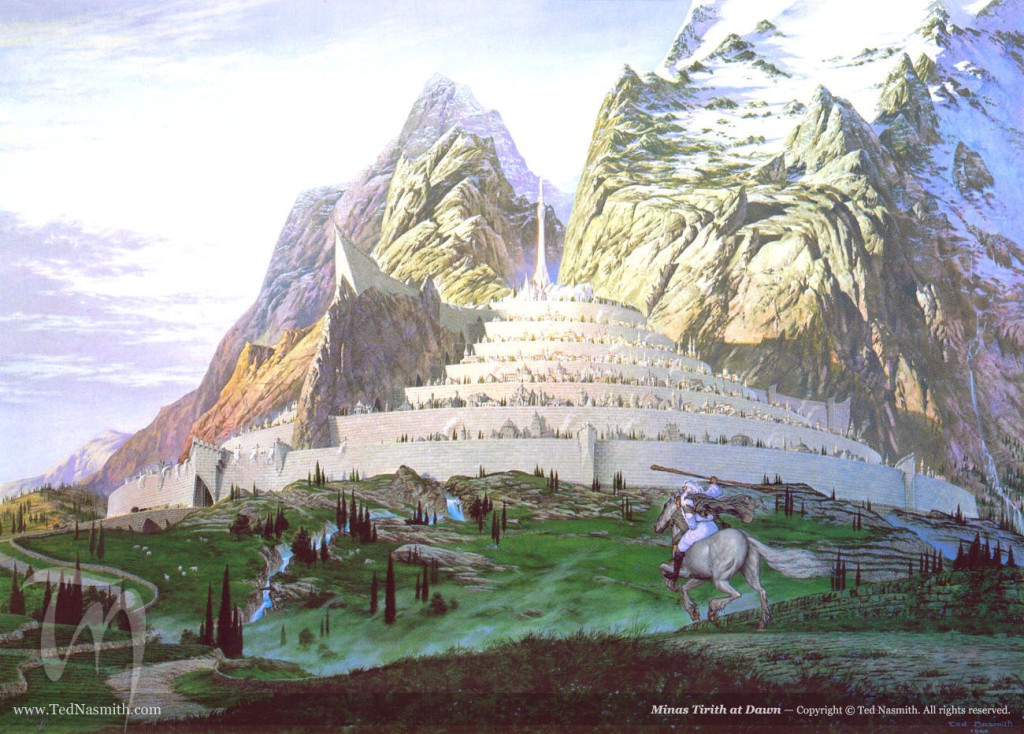

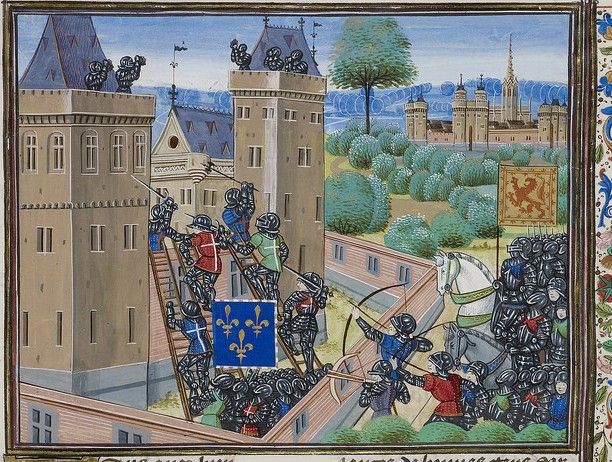

When Helm’s Deep is attacked,

(JRRT)

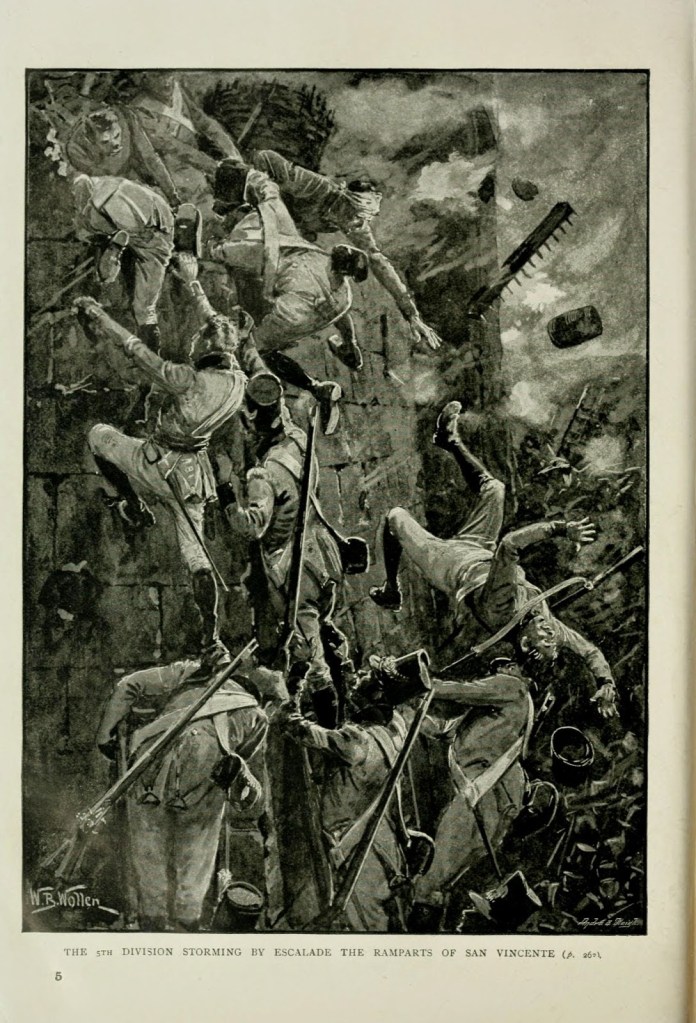

the orcs’ original method is perhaps the worst in the repertoire: escalade—that is, putting ladders up against a wall, then climbing up them. You can imagine why I call it the worst—

the attackers are visible all the way up the ladders and:

1. they can be pushed off

2. the ladders can be pushed off

3. people can whack you when you reach the top

4. people can shoot you on the way up

5. people can drop things on you on the way up

(In several historical assaults, ladders were found to be too short, adding an extra difficulty.)

Such attacks usually only succeed if:

1. they are a surprise (this happened at the terrible siege of Badajoz in 1812—the French garrison was too focused in one direction and some of the British attackers climbed up the back of the fortress–)

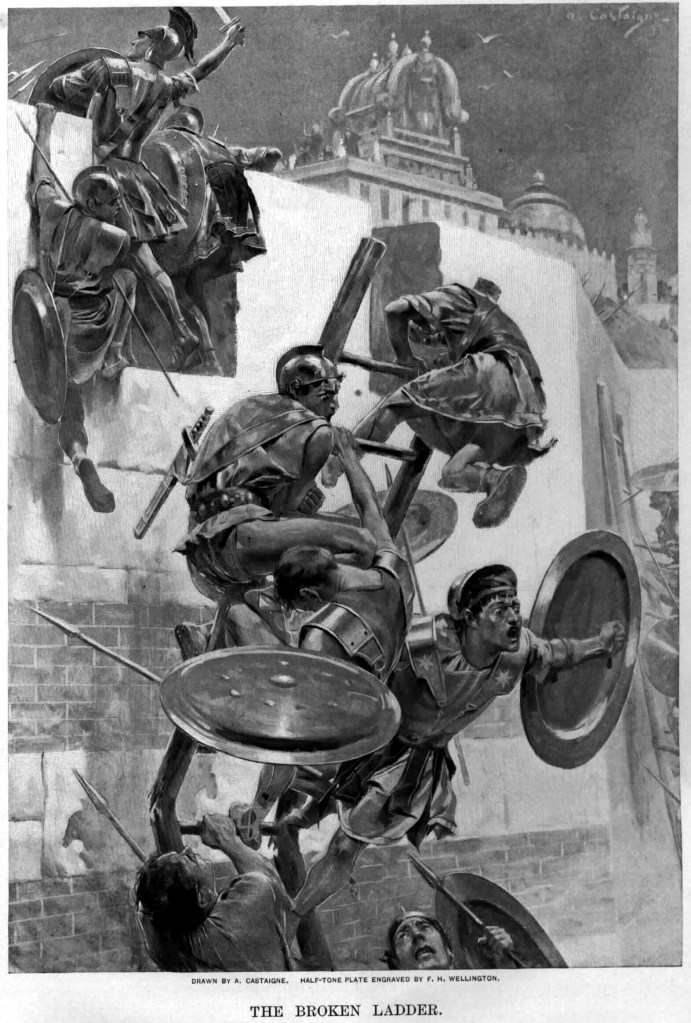

2. the attackers can pin down enough of the defenders with archery/gunfire to allow the climbers to reach the top—and an attack can still fail if those at the top aren’t supported by others coming up behind them—Alexander the Great almost died when he was isolated after scaling an enemy wall (reinforcements overburdened the ladders and they broke—see Arrian The Anabasis of Alexander, Book VI, Sections 9-10—which you can read in translation here: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/46976/pg46976-images.html#Page_329 )

The orcs, however, are concealing a secret weapon—

“Even as they spoke there came a blare of trumpets. Then there was a crash and a flash of flame and smoke. The waters of the Deeping-stream poured out hissing and foaming: they were choked no longer, a gaping hole was blasted in the wall. A host of dark shapes poured in.

‘Devilry of Saruman!’ cried Aragorn. ‘They have crept in the culvert again, while we talked, and they have lit the fire of Orthanc beneath our feet.’ “ (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 7, “Helm’s Deep”)

And it’s not just Saruman’s “Devilry”—

“The bells of day had scarcely rung out again, a mockery in the unlightened dark, when far away he saw fires spring up, across in the dim spaces where the walls of the Pelennor stood. The watchmen cried aloud, and all men in the City stood to arms. Now ever and anon there was a red flash, and slowly through the heavy air dull rumbles could be heard.

‘They have taken the wall!’ men cried. ‘They are blasting breaches in it. They are coming!’ “ (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 4, “The Siege of Gondor”)

I think that we can assume that “the fire of Orthanc” is, in fact, gunpowder.

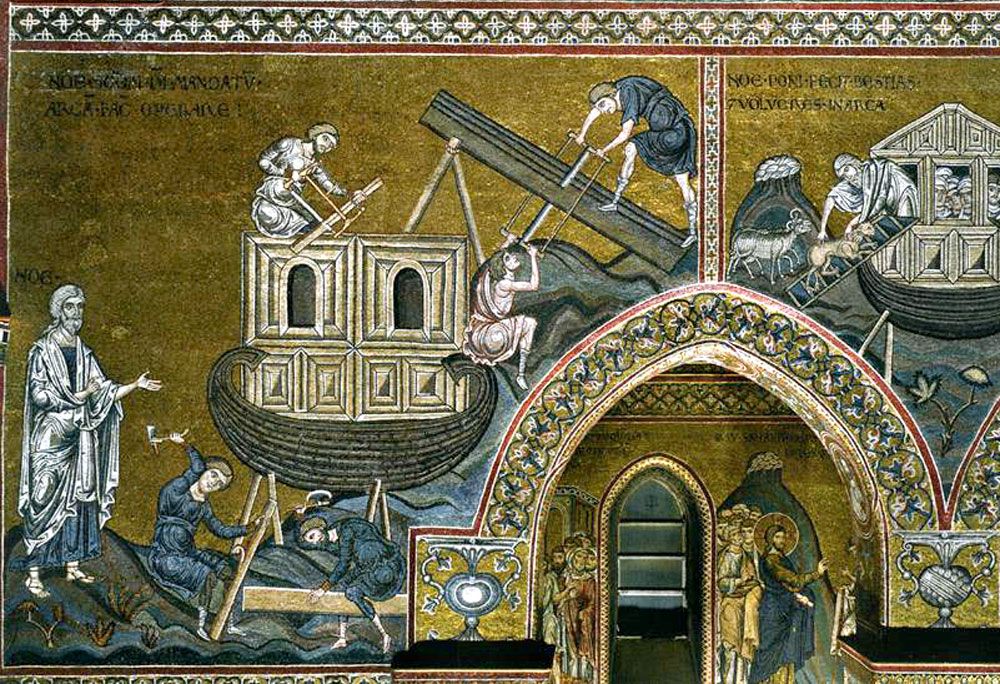

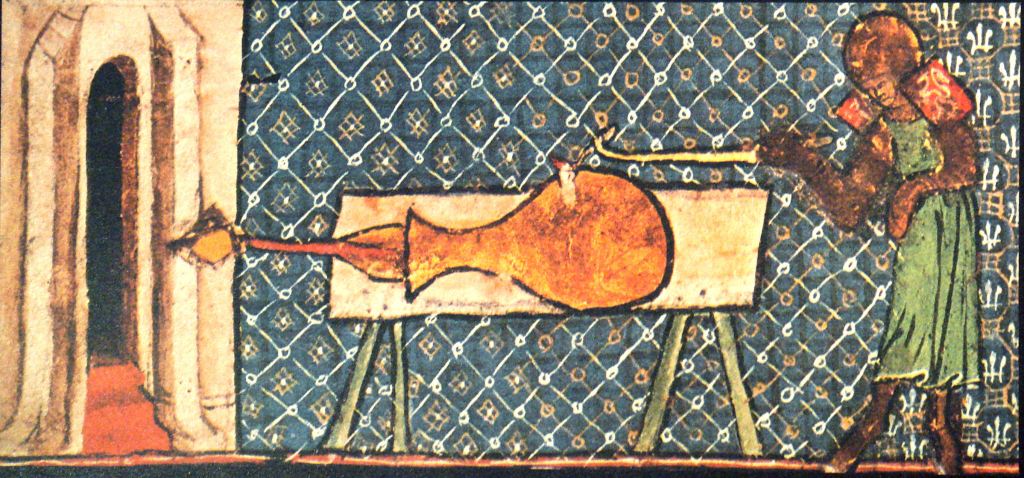

In our Western world, the first known mention of it was by Friar Roger Bacon in the mid-13th century,

and the first known depiction of a gunpowder weapon dates from the early 14th century.

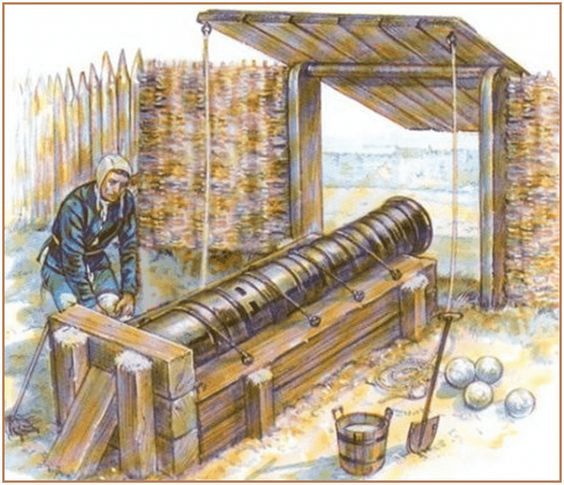

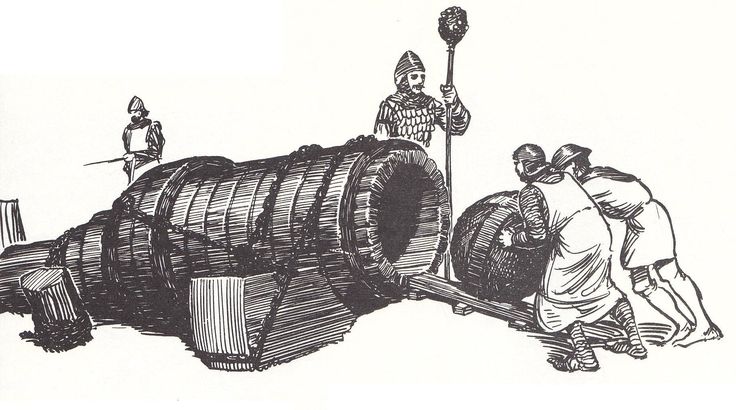

The only uses in The Lord of the Rings are for what would be called, in later times, “mines”. In our Middle-earth, medieval technology further developed the use of gunpowder into bigger, deadlier forms—early cannon, called “bombards”

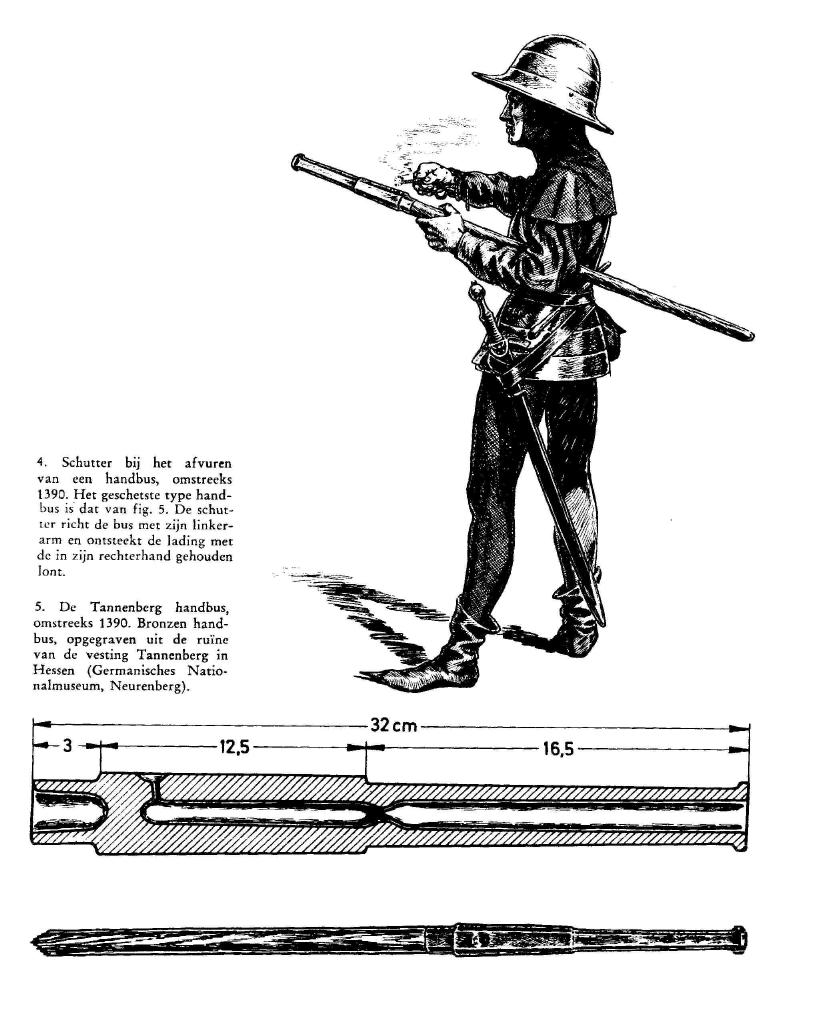

and miniaturized them as “handgonnes”.

(Liliane and Fred Funcken)

What if Saruman—and Sauron—had had time to develop their “fire of Orthanc”?

This is how we usually see orcs and their armament—all medieval—spears, swords, bows.

(Alan Lee)

Suppose, however, that there had been further armament. Imagine orcs with handgonnes, for example.

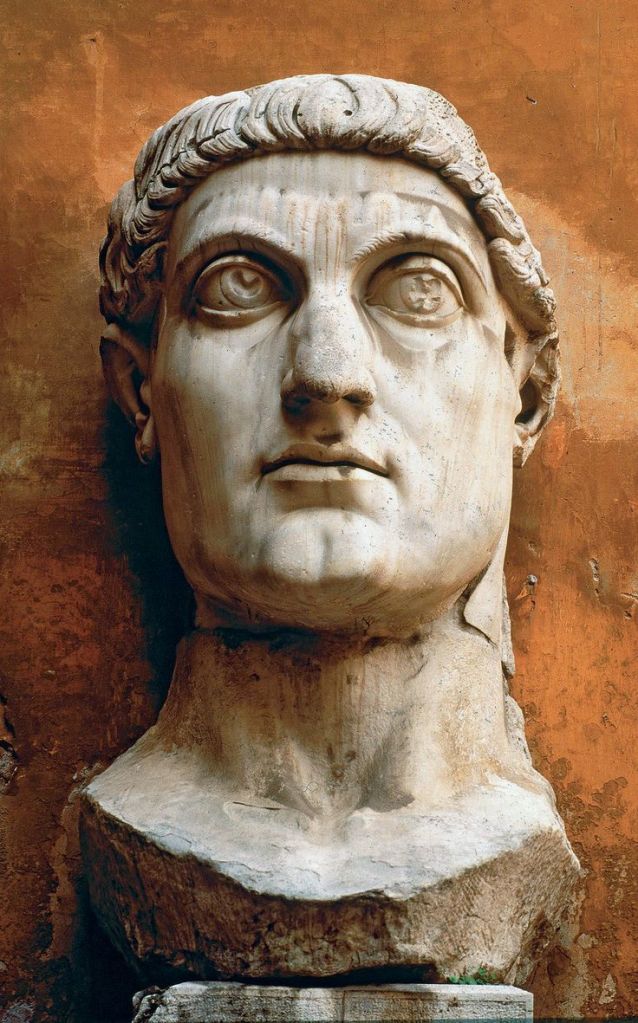

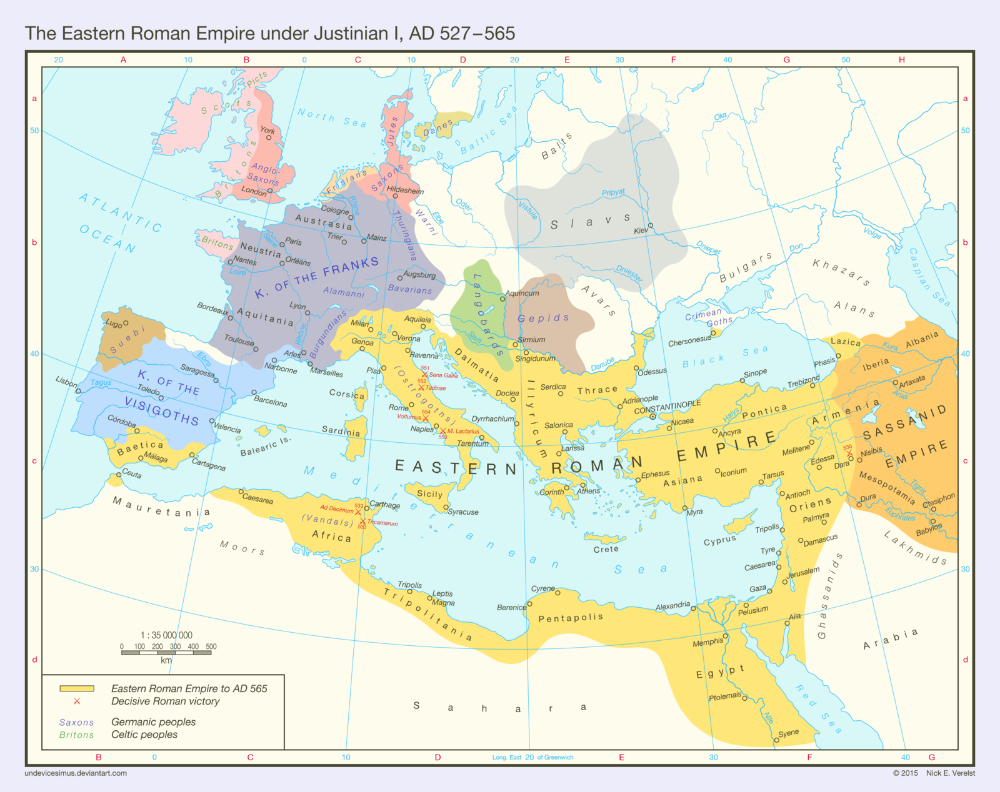

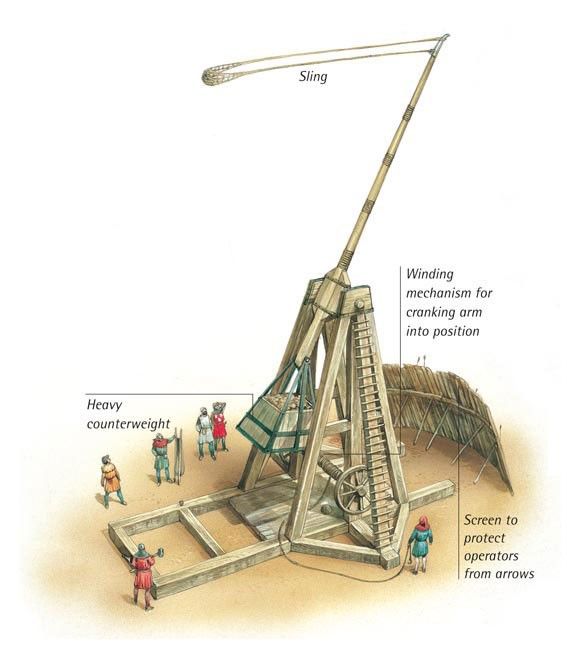

And, instead of massive stone-throwers employed to break down the walls of Minas Tirith—also a medieval weapon—

giant bombards.

It was weapons like these, in 1453, which broke holes in the ancient walls of Constantinople,

allowing the Turkish besiegers to enter a place which only once before, in its 1000 year plus history, had been broken into.

And why stop there?

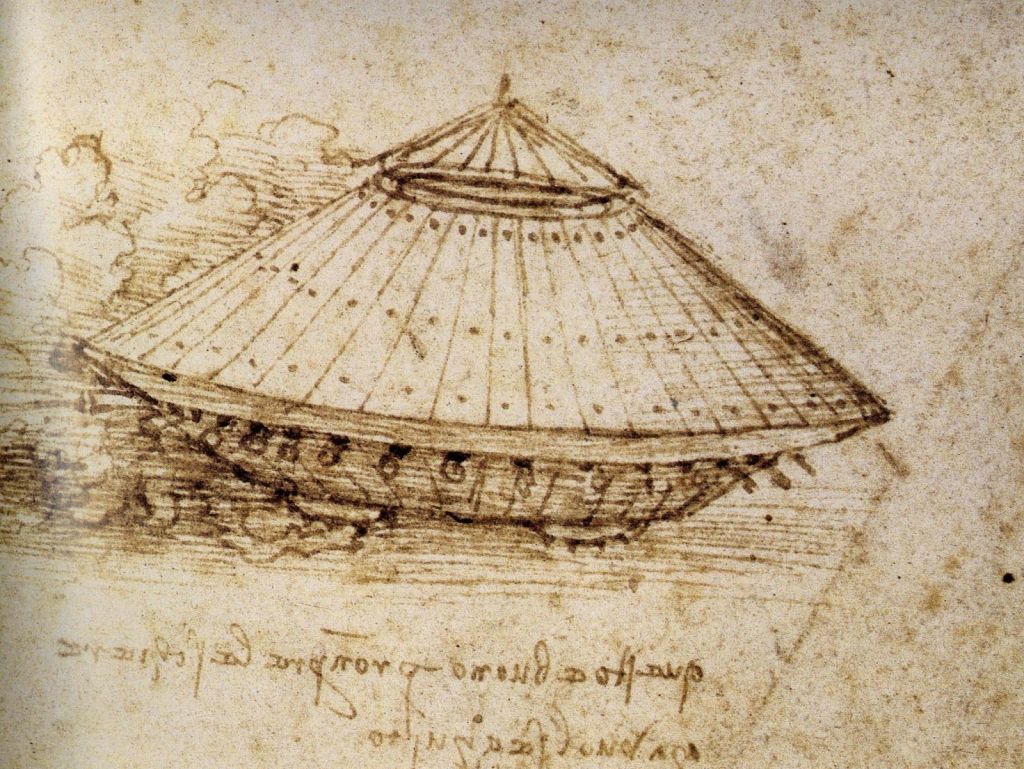

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

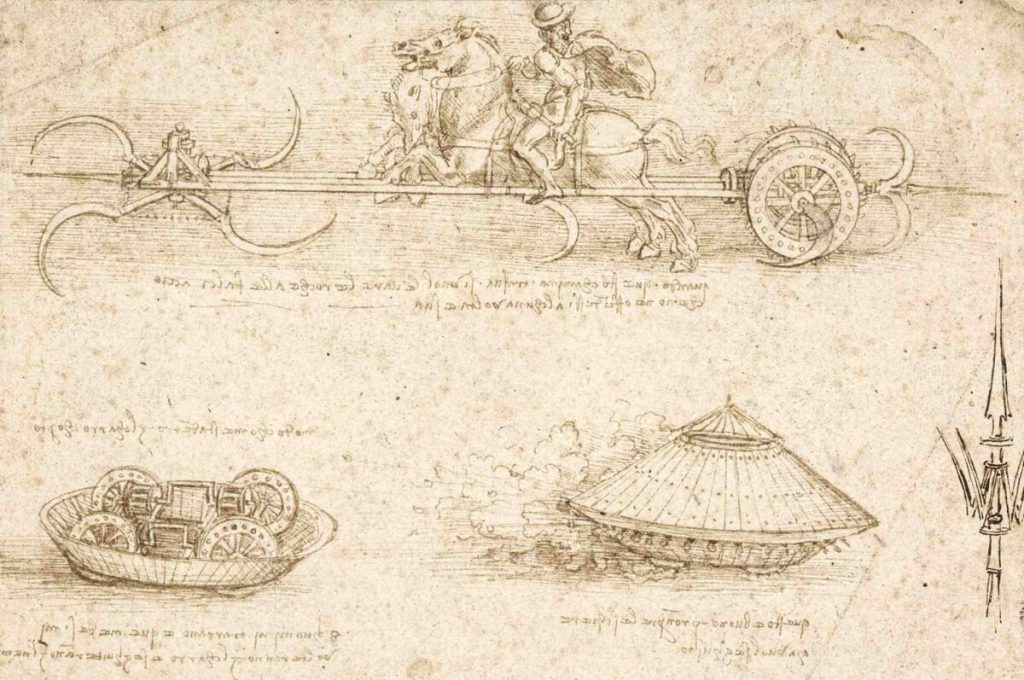

was born only the year before the fall of Constantinople, just at the very end of the Western Middle Ages. In 1487, he sketched this—

which, in terms of much of its technology, was possible in 1487, although it would have been more than a little crowded inside with all of those guns, especially when they jerked backwards in the recoil which would have come with firing them. Fortunately for the West, da Vinci doesn’t appear to have figured out a useful way of propelling his invention

and it was only in the early 20th century that the internal combustion engine could be employed to move such a metal monster.

Consider, however, if the opponents of the West in the later Third Age had developed what clearly they had begun. Seeing such approaching, on foot or, worse, in an armored vehicle, what could Rohirrim or Gondorians have done beyond believing what Qui Gon had tried to warn Boss Nass about:

Dos Mackaneeks!

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

Remember the places where tanks are vulnerable,

and remember, as well, that there’s always

MTCIDC

O