Tags

As always, dear readers, welcome.

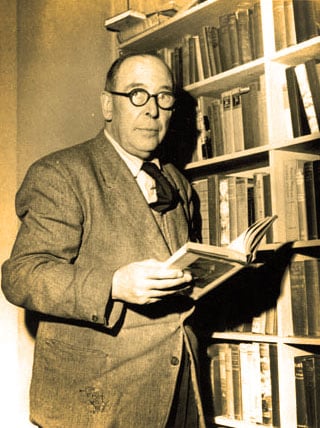

C.S. Lewis once remarked that, “You can’t get a cup of tea large enough or a book long enough to suit me.” (from a transcript of a lecture given by Lewis’ sometime editor and biographer, Walter Hooper—here’s the whole piece: https://www.historyspage.com/post/cs-lewis-inklings-memories-walter-hooper )

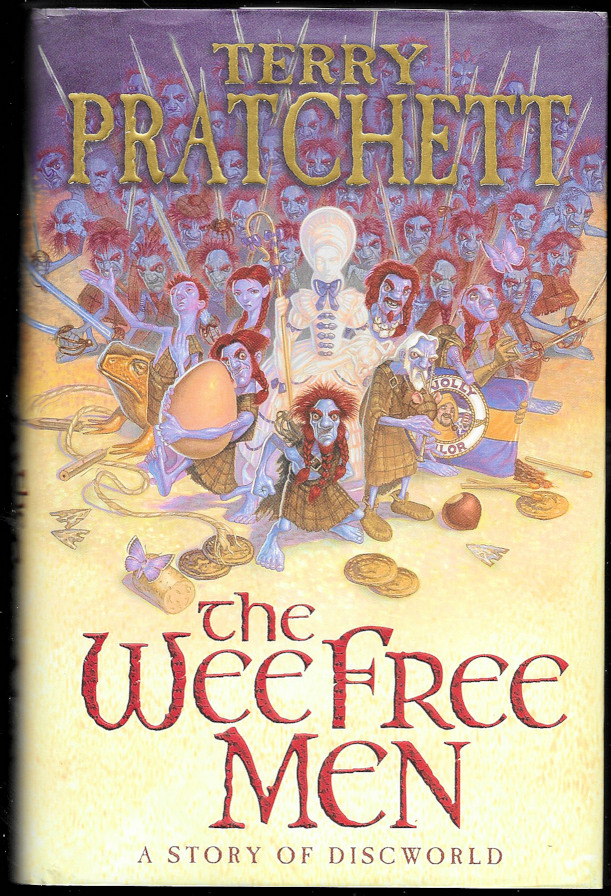

Considering my affection, not only for

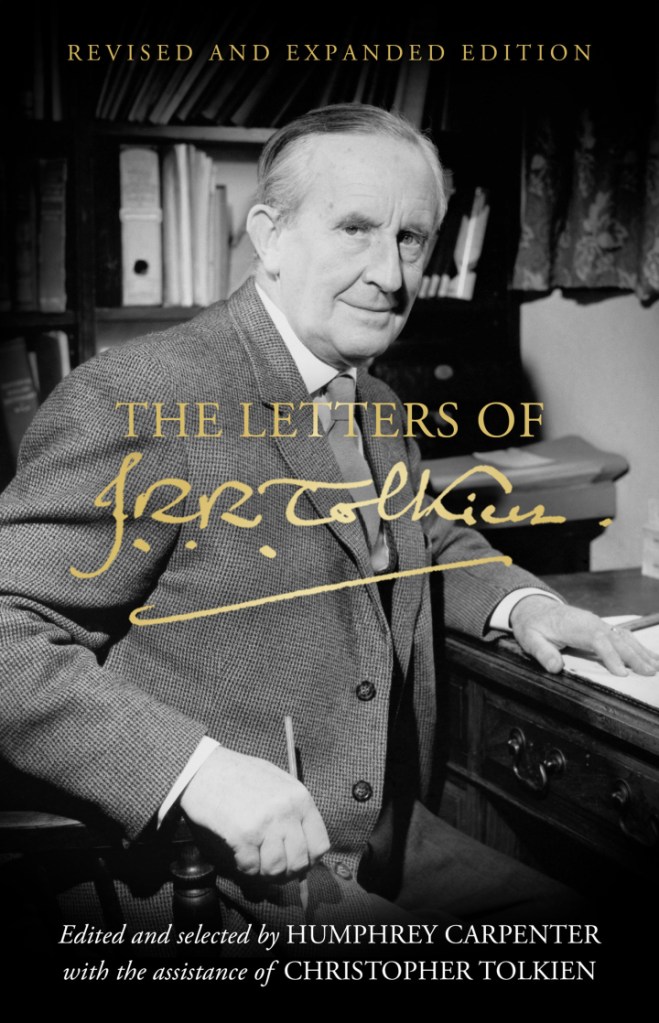

but

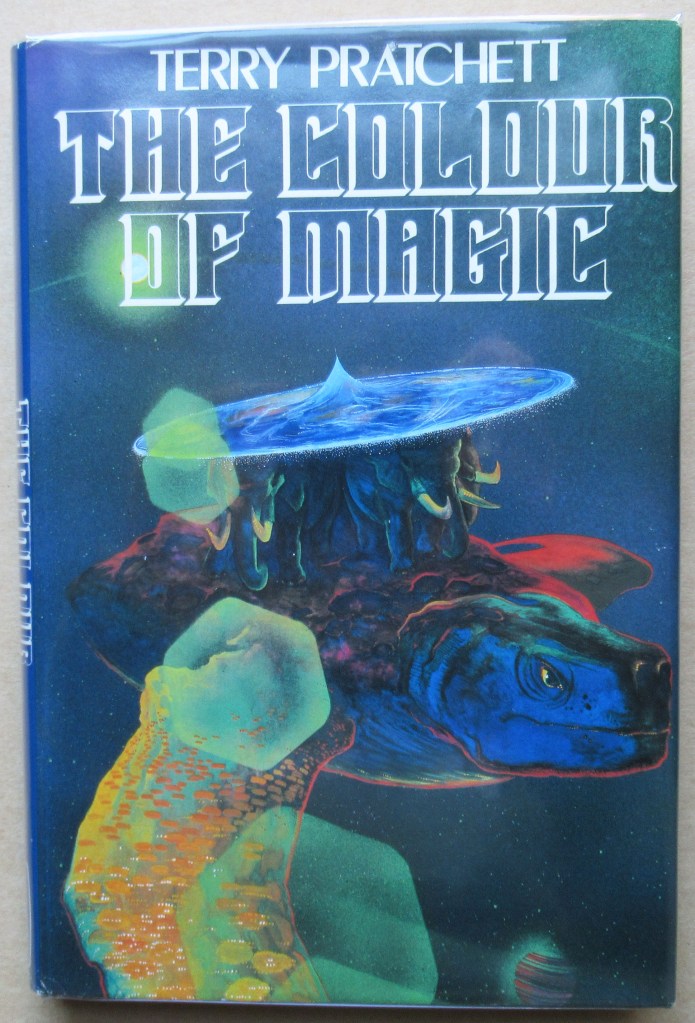

and such works as these,

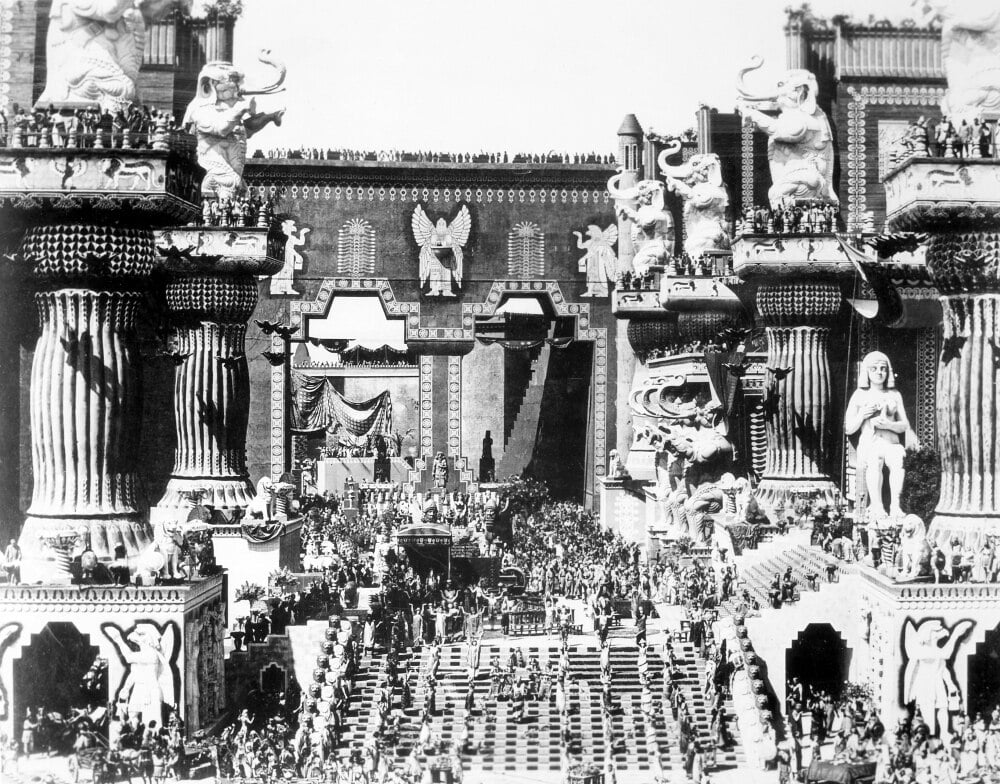

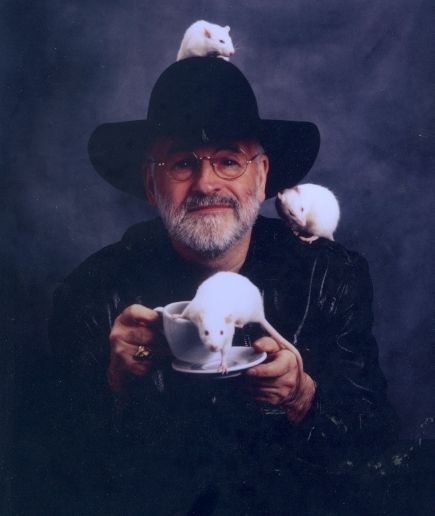

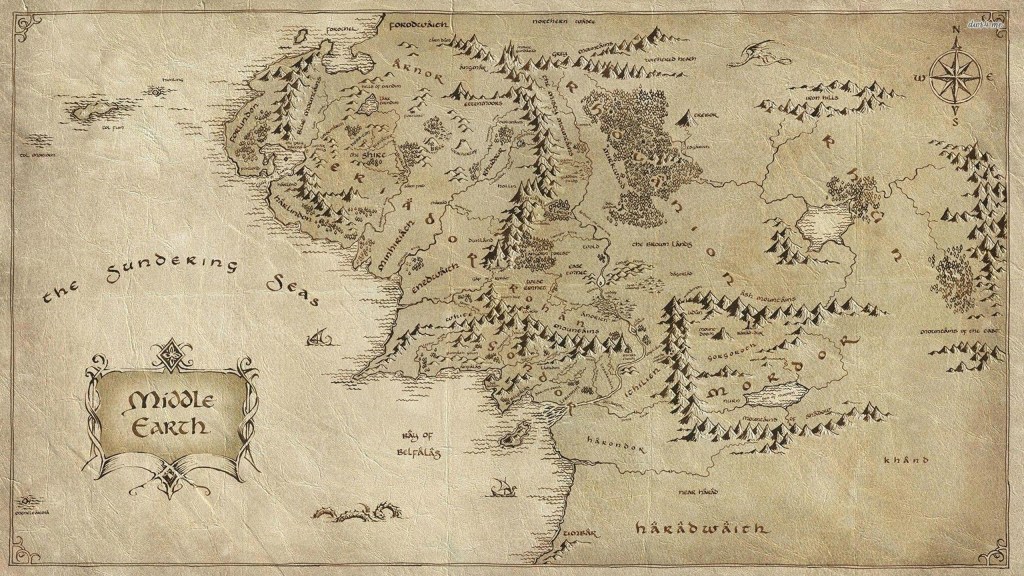

as well as a life-long love of

(but such a small cup!),

it’s clear that I’m in whole-hearted agreement with “Jack”, as his brother, “Warnie”, had named him in childhood.

In this spirit, during the early fall, I embarked upon a project I’ve long told myself I would do: read the whole of The Thousand Nights and One Night—in translation, unfortunately.

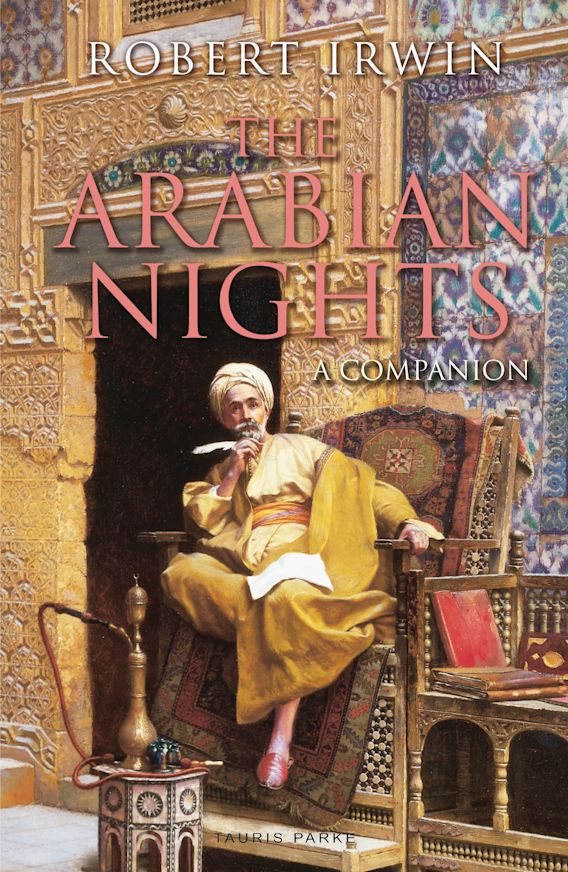

I began with this introduction—

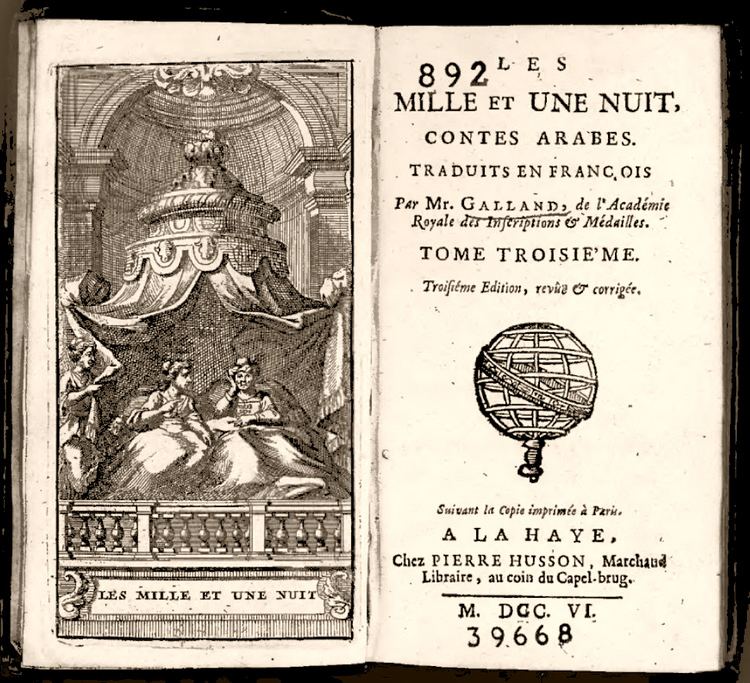

From earlier work (and postings) on the origins of “contes des fees”, as early French authors—the creators of our literary stories, like “La Belle et La Bete”, originally written by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve in 1740, but better known by the revised 1756 version of Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont–called them—I knew something of the story of how English-speakers first encountered The Arabian Nights in the so-called “Grub Street” edition of 1706, itself an anonymous translation of Antoine Galland’s (1646-1715)

Les Mille et Une Nuits of 1704-1717.

I soon discovered, however, just how much more there was to know. In chapters with intriguing titles like “Beautiful Infidels” and “Oceans of Story”, the author, Robert Irwin, laid out the complex history of this vast collection, which most of us know from tales which aren’t even in the main collection, “orphan stories” like “Aladdin”

(Albert Robida, 1848-1926)

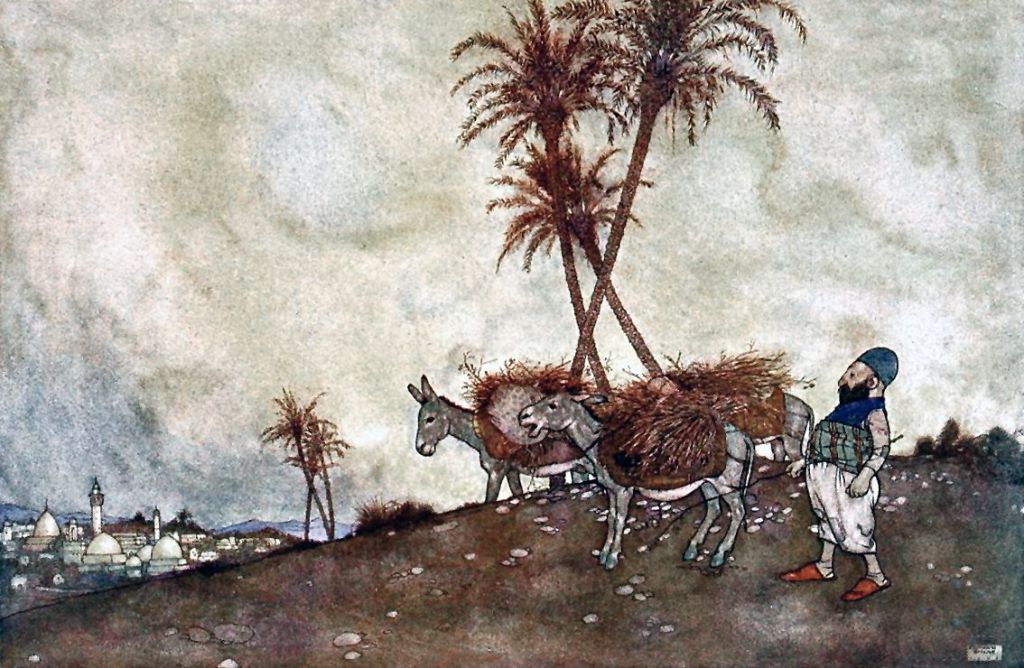

and “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.”

(Edmond Dulac, 1882-1953)

(For more on translations, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Les_mille_et_une_nuits and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Translations_of_One_Thousand_and_One_Nights )

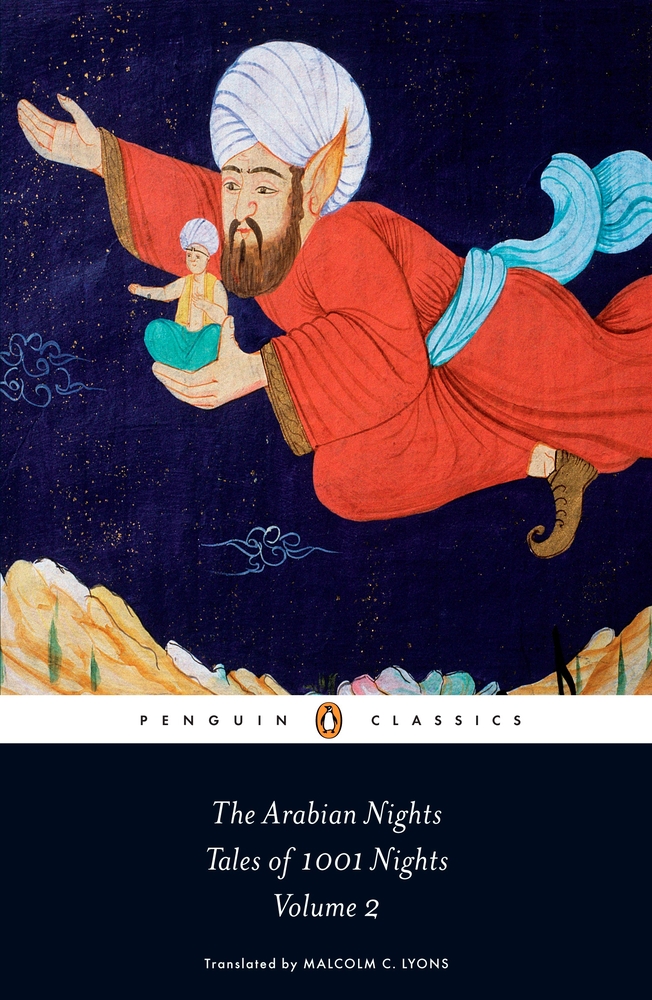

Armed with the knowledge Irwin provided, it was time to begin reading. I chose what seemed the best translation in English, by Malcolm C. Lyons, in a set of four Penguin volumes and launched into the first.

I imagine that you know the general frame: King Shahryar learns that his wife is unfaithful. To keep himself from being cuckolded again, he marries a new bride every night and has her beheaded the next morning. His Vizier’s daughter Shahrazad, decides to stop this by marrying the Sultan but then, telling one story after another, to keep him so interested night after night by stopping a story at the night’s end without finishing, to force him to suspend his murderous habit to find out what happened next.

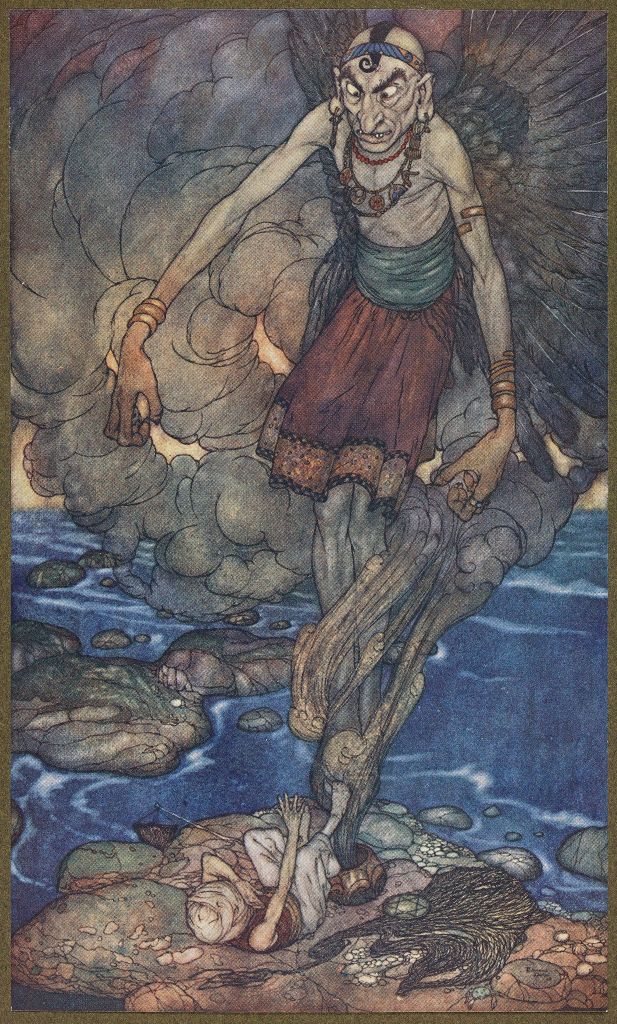

(Another Dulac. If you’d like to see more of his gorgeous illustrations, look here: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/51432/pg51432-images.html )

Finally, after 1001 stories (or perhaps a few more), he decides not to continue murdering brides, Shahrazad is saved, and, presumably, lives happily ever after (really? Could you ever trust this man not to change his mind?).

I’ve just finished Volume 1 and set off into Volume 2

and it’s been an extremely interesting experience. Unlike a long novel, like War and Peace, where we follow the adventures of a few main characters—Natasha, Pierre, and Andrei—even when surrounded by a host of other characters (and Tolstoy’s book has a flood of them), in The Arabian Nights, except for the shell characters—the king, the story-teller, and the story-teller’s sister, who can act as a prompter–the main characters can change often, sometimes making it difficult to remember who is doing what with or to whom. More than once, I had to turn back a page, scan paragraphs, asking myself, “Who is Ali ibn Ishaq again?” or “Is this the brother—or is it brother-in-law? And is this the same slave who…?” As well, this unexpurgated text is filled with poetry, some of which is reflective of something going on in the story, some—maybe more than some—is simply poetry which has been inserted into the text. Because it might be part of the story, I continued to read it, but often it was just what it appeared to be: poetry inserted for some reason I didn’t understand into the text.

At the same time, as story spawned story, stories were interwoven, stories linked themselves here and there into complex narratives, there was a certain hypnotic quality to it which kept me reading, not so much because the characters had looped me in as that the method of telling itself had. I might not care about why X was beheaded, but I was certainly interested to understand how the story had turned in that direction and he was. In other words, just as Shahrazad had seduced the king with her telling into wanting more and more, so she had seduced me into reading on, always wondering, “Where is this going and how will it end?” And—just as interesting—“How will we move to the next story?”

At over 950 pages on average for each of 4 volumes, each of these would surely have (at least temporarily) satisfied C.S. Lewis—but where would we ever find a tea cup large enough to keep him—and me—going?

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

Uncork no bottle unless you’ve already planned how to deal with the djinn inside,

And know that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O