Tags

dialogue, Fantasy, lotr, Mouth of Sauron, Nazgul, Saruman, The Lord of the Rings, thou-vs-you, Tolkien, villain, Witch-King of Angmar

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

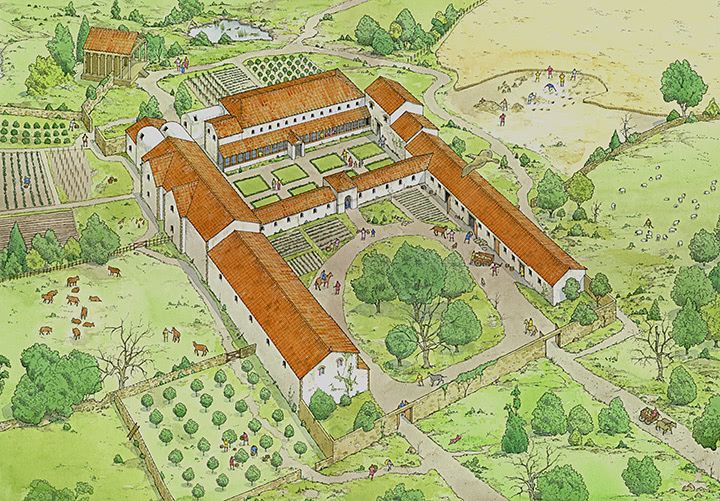

It is sometimes surprising to see how social class can influence vocabulary. For instance–

this is a Roman villa—

in Pompeii, where wealthy city people might live.

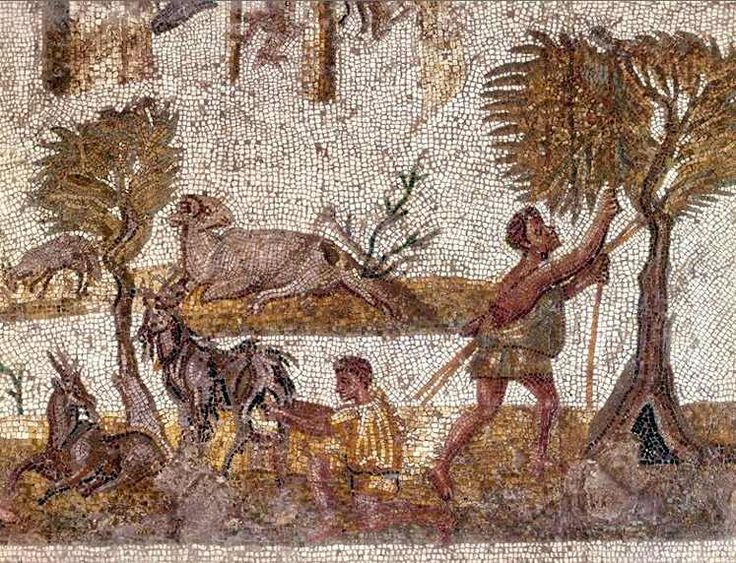

And this is a country villa—

(Billl Donohoe)

which, in its more elaborate form, might offer some of the comforts of a city dwelling, but would often also be a working farm and here are a couple

of Roman farm workers (probably slaves), each of whom, as someone attached to a villa, could be called a villanus—and I’m sure that you see where this is going: rural people could be uncultivated (no pun, there) and therefore crude and, by a snobbish leap of imagination from 12th-century Old French to mid-16th century English, people who could be expected to be involved in the worst antisocial behavior: crime. (For more on this, see: https://www.etymonline.com/word/villain )

In the previous posting, we began examining Tolkien’s villains in The Lord of the Rings, and how Tolkien, with his wonderful ear for language (and a great dramatic gift), used speech to depict their characters, as well as their behavior.

Since Sauron provides such a small sample of speech, we began with Saruman,

(the Hildebrandts)

who, as reported by Gandalf in Book One, could be by turns, sarcastic, conspiratorial, falsely chummy, and coldly imperious, all the while, though only at first obliquely, attempting to persuade Gandalf to reveal to him the location of The Ring and, in doing so, revealing to Gandalf not only his corrupt ambition, but also his lack of awareness of how much that corruption came from his communication with Mordor.

(the Hildebrandts)

In this posting, I want to continue that examination by extending it down the social scale of villains, beginning with the Nazgul, who, as former kings, might be thought of as next after Saruman.

(Mark Ferrari—new to me, but I like the energy of this and you can see more at: https://www.markferrari.com/image-archives )

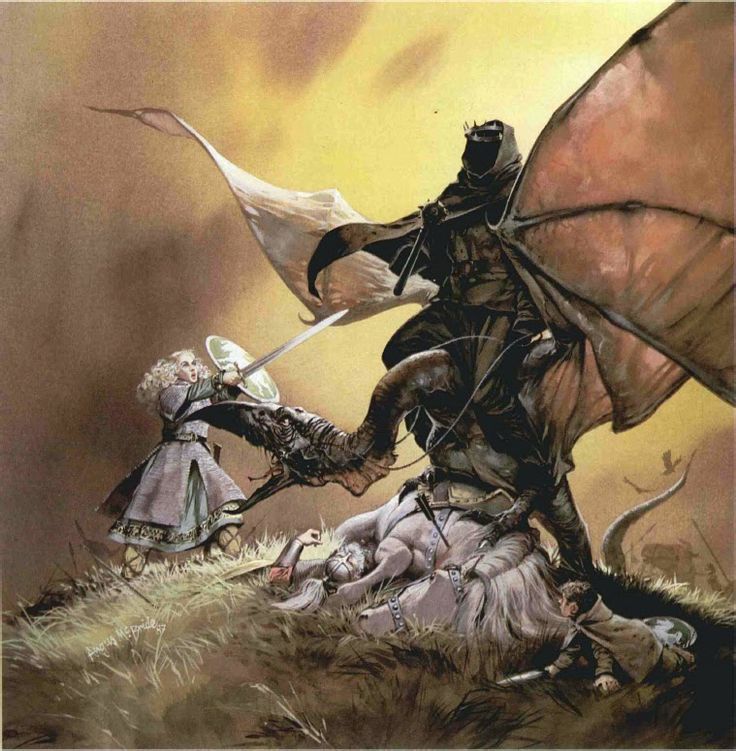

On the whole, unlike Saruman, who gives away so much in his speech, they don’t have much to say for themselves, but their leader, the Witch-king of Angmar,

(Angus McBride)

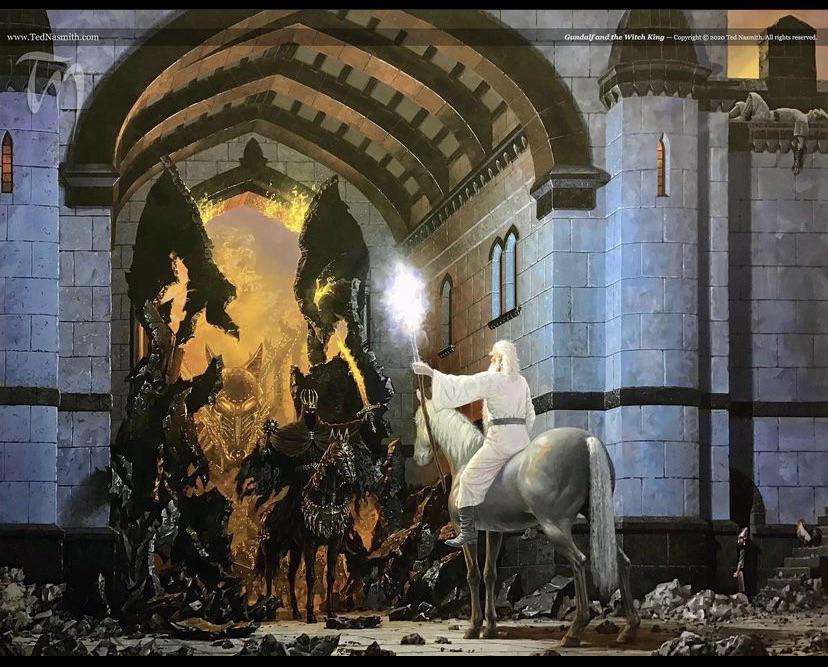

has two bits of dialogue: first, when he encounters Gandalf at the broken gate of Minas Tirith,

(Ted Nasmith)

where he speaks briefly in a threat:

“ ‘Old fool!’ he said. ‘Old fool! This is my hour. Do you not know Death when you see it? Die now and curse in vain!’” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 4, “The Siege of Gondor”)

This only shows his (misplaced) contempt for Gandalf, but he addresses Gandalf as an equal in using “you”, rather than as an inferior, as when he confronts Eowyn:

“ ‘Come not between the Nazgul and his prey!’ “

The Witch-king is ancient—being from the Second Age of Middle-earth—and therefore we might expect his speech to sound archaic, even if here he uses the Common Speech of everyone else we see in The Lord of the Rings, and we see it here with this inverted construction. If it were a person from the present, we might expect “Don’t come” or perhaps “Don’t you come”, but “Come not” immediately suggests a speaker from an earlier time.

He continues:

“ ‘Or he will not slay thee in thy turn.’ “

And note here the archaic “thee” (the accusative/dative/ablative of “thou”), which serves a double purpose: on the one hand, suggesting the Witch-king’s great age and, on the other, this is how a superior would speak to an inferior (as in the case of the Romance languages—where French even has verbs for using “you” vs “thou”—vouvoyer vs tutoyer).

And continues:

“He will bear thee away to the houses of lamentation, beyond all darkness, where thy flesh shall be devoured, and thy shrivelled mind be left naked to the Lidless Eye.’ “ (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 6, “The Battle of the Pelennor Fields”)

The Witch-king persists in his use of “thou”, but then becomes what I feel is quite Biblical in “the houses of lamentation”—where is this place? My immediate thought was that it was the same place where Gollum was tortured (we get a hint of this in Gandalf’s long explanation in The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 2, “The Shadow of the Past”) and where the Mouth of Sauron suggests that Frodo was taken (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 10, “The Black Gate Opens”). As to its name, I was reminded of “The Book of Lamentations” in the Judeo-Christian Bible, a collection of laments over the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians in 587/6BC.

(James Tissot, 1836-1902—actually Jacques Joseph Tissot, a very interesting late-Victorian French artist who did much of his later work in England, where he—or his name, at least—became Anglicized. You can read about him and his art here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Tissot )

Sections of “Lamentations” are read during Lent, in Christian services, and we can assume that JRRT, as a practicing Catholic, was well aware of the book. (You can read more about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_Lamentations )

Wherever the idea came from, the Witch-king continues it in an extremely graphic manner, repeating his use of “thou” to the end of his threat, at the same time.

We see this use of “thou” once more from another on that social scale, the Mouth of Sauron.

(Douglas Beekman—you can read a little more about him here: https://www.askart.com/bio/Doug_L_Beekman/122294/Doug_L_Beekman )

This is, again, an ancient figure, as we’re told that “…he was a renegade, who came of the race of those that are named the Black Numenoreans”—that is, followers of Sauron in the Second Age—and he begins as Saruman began, with contempt—

“ ‘Is there anyone in this rout with authority to treat with me?’ “

“Rout” is an archaic word for “rabble”, so the Mouth is already suggesting that, in comparison with him, there is no one of stature with whom he could speak. And he goes on—

“ ‘Or indeed with wit to understand me?’ “

He’s establishing his bargaining position here: he’s of higher social standing and smarter than anyone he faces and he continues, addressing Aragorn:

“ ‘It needs more to make a king than a piece of Elvish glass, or a rabble such as this, Why, another brigand of the hills can show as good a following!’ “

So far, then, the Mouth shows arrogance—but his next behavior shows that, underneath that arrogance is cowardice—

“Aragorn said naught in answer, but he took the other’s eye and held it, and for a moment they strove thus; but soon, though Aragorn did not stir or move hand to weapon, the other quailed and gave back as if menaced by a blow. ‘I am a herald and ambassador, and may not be assailed!’ he cried.”

(And this is where Jackson’s portrayal in the film version of the scene fails completely, as Aragorn then cuts him down, which no respectable king—or even knight—would do, as the Mouth is correct in that heralds and ambassadors, traditionally, could claim immunity.)

Gandalf reassures him, although he also cautions him that that immunity might not last forever, before the Mouth continues:

“ ‘So!’ said the Messenger. ‘Then thou art the spokesman, old grey-beard?’ “

This is insulting in several ways: first, that use of “thou”, as though to an inferior; second, as the Mouth clearly recognizes Aragorn, so he would recognize Gandalf, and calling him “old grey-beard” has the same effect as when the Witch-king earlier called him “old fool”.

He then indirectly admits that he does, indeed, recognize Gandalf:

“ ‘Have we not heard of thee at whiles, and of thy wanderings, ever hatching plots and mischief at a safe distance? But this time thou hast stuck out thy nose too far, Master Gandalf, and thou shalt see what comes to him who sets his foolish webs before the feet of Sauron the Great.’ “

Vocabulary is key here: “wanderings”, “hatching plots and mischief”, sticking out “thy nose”, “foolish webs”, all suggest denigration, keeping with the Mouth’s original address, which painted the Gondorians and their allies as a mob of bandits, with no legitimacy to address the Messenger of Sauron, or even the IQ to do so.

Pippin recognizing Frodo’s mithril coat gives the Mouth the chance to continue that denigration, calling Pippin “imp” and “brat” and calling the Shire “little rat-land”, before going on to name the conditions Sauron demands, both for the return of Frodo and for “peace” between him and the allies, conditions which are simply surrender in other terms.

So far, by his very language, the Mouth has attempted to dictate the scenario, using “we” as if it were Sauron himself speaking, attempting to suggest that Sauron is the master of the situation and that he, as Sauron’s spokesman, is in sole charge of the parley, but it’s interesting to see how he responds when spoken to in the same way by Gandalf, who has revealed his own power, pulling the mithril coat and others of Frodo’s possessions from the Mouth’s hands.

“ ‘…Get you gone, for your embassy is over and death is near to you. We did not come here to waste words in treating with Sauron, faithless and accursed; still less with one of his slaves. Begone!’ “

The Mouth’s reaction is the very opposite of his original self-depiction at the beginning of the parley: instead of mocking and presenting himself as above the level of those on the other side, he is literally speechless—and more than mute, being likened to a beast with no ability to communicate at all:

“Then the Messenger laughed no more. His face was twisted with amazement and anger to the likeness of some wild beast that, as it crouches on its prey, is smitten on the muzzle with a stinging rod. Rage filled him and his mouth slavered, and shapeless sounds of fury came strangling from his throat.” (The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 10, “The Black Gate Opens”)

So, the Mouth is dropped into the Animal Kingdom by Gandalf’s words (and notice that archaic “Get you gone!”—the archaism we hear from the Witch-king seems to be catching) and, in the third part of the posting, we’ll drop lower in the social scale, as well.

Stay well,

Imagine how useful “thou” and “thee” might be in English today,

And remember that, as ever, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS I recently happened upon a very useful article on illustrating Tolkien which I want to pass on to you here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illustrating_Middle-earth I love looking at all of the different ways in which artists, all the way back to the 1960s, imagine Tolkien’s work.