Tags

Barrow-wight, bog bodies, bog sacrifices, bogs, Danish National Museum, de-bello-gallico, Dr Seuss, Fionn mac Cumhaill, Frodo, heroic burials, human sacrifice, La Tene, sacrificial-objects, The Lord of the Rings, Thomas Pennant, Tolkien, Tom Bombadil, Vimose

As always, dear readers, welcome.

What’s going on here?

“He turned, and there in the cold glow he saw lying beside him Sam, Pippin, and Merry. They were on their backs, and their faces looked deadly pale; and they were clad in white. About them lay many treasures, of gold maybe, though in that light they looked cold and unlovely. On their heads were circlets, gold chains were about their waists, and on their fingers were many rings. Swords lay by their sides, and shields were at their feet. But across their three necks lay one long naked sword.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 8, “Fog on the Barrow Downs”)

(Matthew Stewart–you can see more of his impressive work here: https://www.matthew-stewart.com/ I like his dragons especially.)

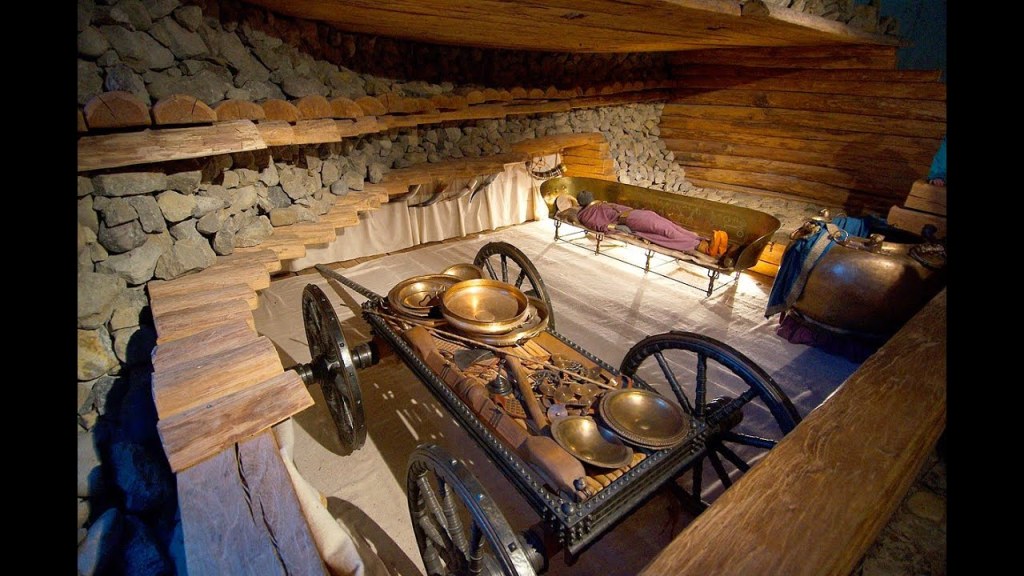

This might appear to look like an early heroic burial, with grave goods piled up,

like this chieftain’s grave from 530BC, found near Hochdorf an der Enz in Baden-Wuerttemberg, Germany—which even has this beautiful wagon (reconstructed—for more see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hochdorf_Chieftain%27s_Grave ).

There is a difficulty, however: none of the hobbits is dead—although that sword across three of their necks suggests that they soon will be.

And I would further suggest that what we’re looking at is the scene of a potential human sacrifice—especially if we add what the narrator calls an “incantation” on the part of the Barrow-wight:

“Cold be hand and heart and bone,

And cold be sleep under stone:

Never more to wake on stony bed,

Never, till the Sun fails and the Moon is dead.

In the black wind the stars shall die,

And still on gold here let them lie,

Till the dark lord lifts his hand

Over dead sea and withered land.”

Human sacrifice had certainly been practiced in Middle-earth. We know that Sauron, defeated temporarily, corrupts the king of Numenor, Tar-Calion (also known as Ar-Pharazon), preaching the worship of the fallen Vala, Morgoth:

“A new religion, and worship of the Dark, with its temple under Sauron arises. The faithful are persecuted and sacrificed. The Numenoreans carry their evil also to Middle-earth and there become cruel and wicked lords of necromancy, slaying and tormenting men… “ (letter to Milton Waldman, late 1951, Letters, 216-217—for more on this see “Melkor/Morgoth/Melqart” 29 June, 2022)

I suspect that Tolkien’s own first experience with such sacrifices may have come from a boyhood reading Julius Caear’s (100-44BC) De Bello Gallico, where he would have found:

“Natio est omnis Gallorum admodum dedita religionibus, atque ob eam causam, qui sunt adfecti gravioribus morbis quique in proeliis periculisque versantur, aut pro victimis homines immolant aut se immolaturos vovent administrisque ad ea sacrificia druidibus utuntur, quod, pro vita hominis nisi hominis vita reddatur, non posse deorum immortalium numen placari arbitrantur, publiceque eiusdem generis habent instituta sacrificia. Alii immani magnitudine simulacra habent, quorum contexta viminibus membra vivis hominibus complent; quibus succensis circumventi flamma exanimantur homines.”

“The whole nation of the Gauls is completely devoted to religious practices and because of this, those who are afflicted with very serious illnesses and those who are involved in battles and dangers either sacrifice men in place of animal victims or pledge that they will sacrifice them and use the druids as the priests for those sacrifices because they think that, unless the life of a person is paid back for the life of a person, the divine will of the immortal gods can’t be appeased and they [even] have sacrifices set up of the same kind at public expense. Others have images of immense size of which the chambers, woven of willow withies, are filled with living people. [So that], when they are set alight, the people, surrounded by flame, are killed.” (De Bello Gallico, Book VI, Sec.16, my translation—you can read more at the invaluable Sacred Texts site here in a parallel Latin/English text: https://sacred-texts.com/cla/jcsr/index.htm )

(This is from Thomas Pennant’s, 1726-1798, A Tour of Wales, 1778. Pennant was a naturalist, antiquarian, traveler, etc etc and one of those wonderful 18th people seemingly interested in everything and eager to report what they discovered. You can read about him here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Pennant but don’t forget to read about his draftsman, Moses Griffith, an equally impressively-talented man: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moses_Griffith_(artist) There is even a Thomas Pennant Society: https://www.cymdeithasthomaspennant.com/eng/t-p.html And you can read the Tour itself here: https://archive.org/details/toursinwales00penngoog/page/n8/mode/2up For more on the idea of the “wicker man”, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wicker_man )

The Romans, with very rare (and early) exceptions, frowned upon human sacrifice, but northern people, before being overwhelmed by the Romans, or too far north for them to conquer effectively, could, as in the case of the Gauls mentioned above, have a different approach to their gods.

Unfortunately, as they were not, like the Romans, extremely literate, what little description we have comes from people like Caesar, curious (and probably horrified) outsiders—and perhaps also propagandists, who wanted to paint those outside the Mediterranean world as savages and therefore worthy of nothing more than conquest.

We do, however, have other and very vivid evidence in the form of archaeological discoveries.

One of these turned up in my last posting, the “Vimose comb” (see “Runing Things”, 13 August, 2025).

The “-mose” in Vimose means “bog/wetland/moorland” in modern Danish, descended from “mosi” in Old Norse and this immediately tells us about a different method of making a sacrifice—and not necessarily a human one—dropping it into water.

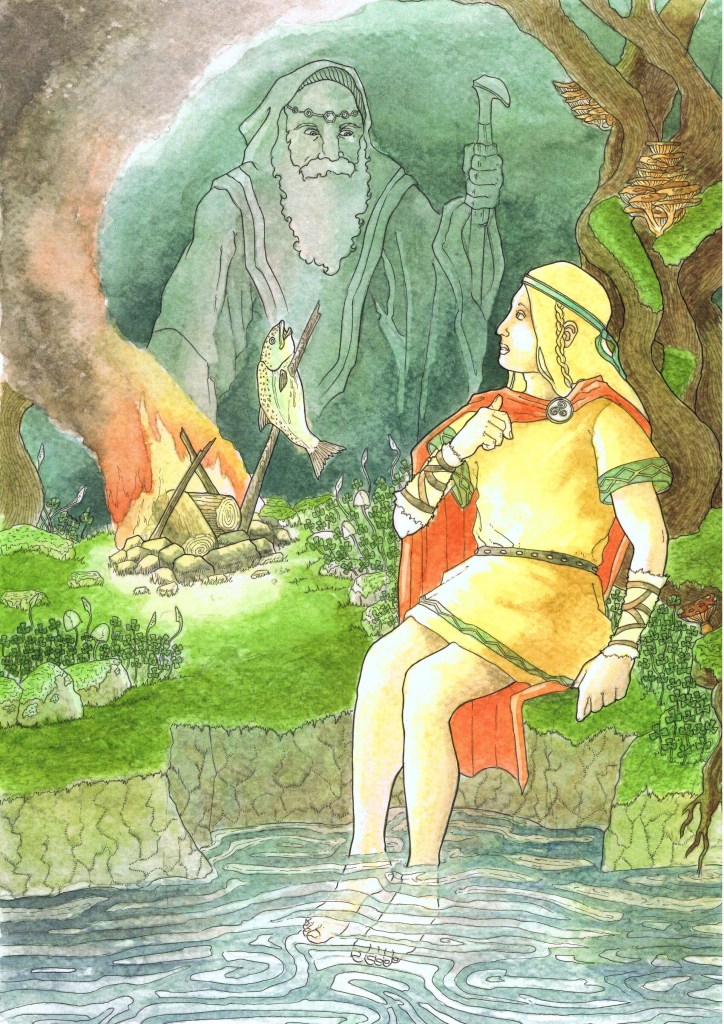

Without local explanation, we can only guess what was thought to happen when the object was deposited. For myself, I’ve always thought of the pool in the story of Fionn mac Cumhaill.

(Marga Gomila—you can see drafts of this work at: https://margagomila.artstation.com/projects/OmEwgv )

This was connected with the otherworld and nuts from hazel trees would fall into the pool from that otherworld, to be consumed by a salmon in our world. Cooking the salmon (caught in this world), Fionn, then a boy, burned his thumb and, putting it into his mouth, gained supernatural knowledge thereby. (See for more: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fionn_mac_Cumhaill and: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wells_in_the_Irish_Dindsenchas There is a similar story attached to the Germanic hero, Sigurd, which you can read in the form Tolkien probably first read it: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/540/pg540-images.html )

So, were these earlier sacrificers dropping in their treasures in hopes of sending them out of this world, presumably to the place where their gods lived?

Certainly the person who dropped the comb into the Vimose must have had some such hope and that person was hardly alone as, to date, about 2500 objects have been recovered from the site. (For more on Vimose, check out this very interesting site: https://ageofarthur.substack.com/p/the-homeland-of-the-angles-and-the See, as well, the Danish National Museum site, with all sorts of short articles on Vimose and other places: https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-early-iron-age/the-weapon-deposit-from-vimose/the-offerings-in-vimose/ )

And it’s not the only site. From Ireland eastwards through much of Germany, there are sites, some more specific, like La Tene, in Switzerland, where there was a huge cache of swords,

(no citation, but it looks like a Peter Connolly)

and Hjortspring, in Denmark, where there was a boat,

and Dejbjerg, also in Denmark, where there was a wagon.

There are animal sacrifices,

(Miroslaw Kuzma–as a sometime horseman, I hesitated to include this illustration.)

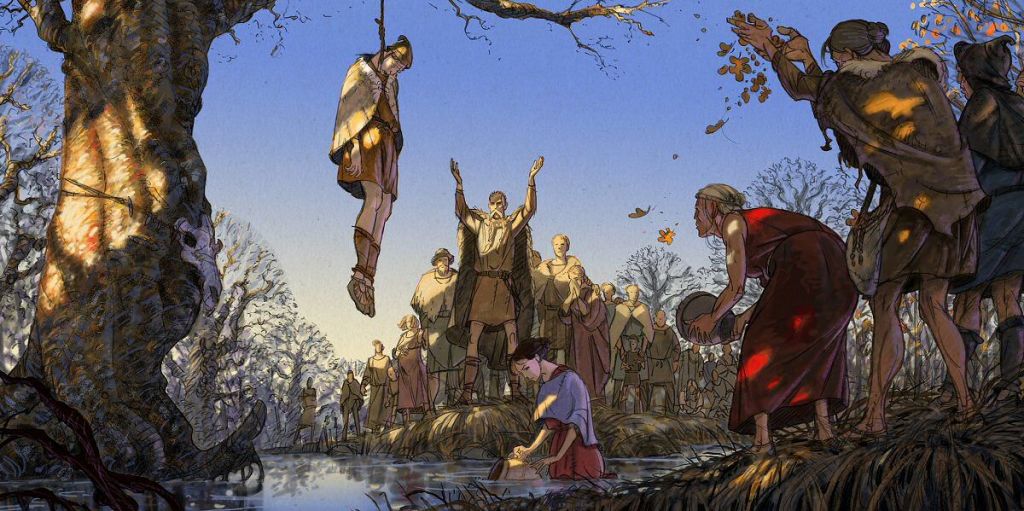

but the most sinister deposits are human ones,

some of whose well-preserved remains would probably have worried those who believed that, once the victim had been dealt with, and sunk in the water, the sacrifice would have been accepted and then the next step would be a god’s. (For more on so-called “bog bodies”, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bog_body )

Although Frodo was responsible for halting what may have been about to be a sacrifice—

“But the courage that had been awakened in him was now too strong: he could not leave his friends so easily. He wavered, groping in his pocket, and then fought with himself again; and as he did so the arm crept nearer. Suddenly resolve hardened in him, and he seized a short sword that lay beside him, and kneeling, he stooped low over the bodies of his companions. With what strength he had he hewed at the crawling arm near the wrist, and the hand broke off; but at the same moment the sword splintered up to the hilt. There was a shriek and the light vanished. In the dark there was a snarling noise.”

It was the appearance of Tom Bombadil, summoned by Frodo, who rescued them all—

“There was a loud rumbling sound, as of stones rolling and falling, and suddenly light streamed in, real light, the plain light of day. A low door-like opening appeared at the end of the chamber beyond Frodo’s feet; and there was Tom’s head (hat, feather, and all) framed against the light of the sun rising red behind him.”

And there was Tom’s incantation—

“Get out, you old Wight! Vanish in the sunlight!

Shrivel like the cold mist, like the winds go wailing,

Out into the barren lands far beyond the mountains!

Come never here again! Leave your barrow empty!

Lost and forgotten be, darker than the darkness,

Where gates stand for ever shut, till the world is mended.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 8, “Fog on the Barrow-downs”)

I wonder whether, about to be consecrated to a god we no longer know of, a victim might have called upon his/her gods, hoping for a similar rescue?

Thanks for reading, as ever.

Stay well,

Avoid barrows—unless they’re wheeled,

(Is this by a medieval Dr. Seuss?)

Definitely stay out of bogs,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

If you’re interested in a scientific explanation for the surprising preservation of some bodies, see: