Tags

Finnish, Gothic, Greek, Joseph Wright, Landscape, languages, Latin, Middle English, Old English, Old Norse, seascape, soundscape, Tolkien, Welsh

As ever, welcome, dear readers.

Everyone knows the term “seascape”—as in this painting by Eugene Boudin (1824-1898)–

(You can learn a little more about him and see a small gallery of his work here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eug%C3%A8ne_Boudin and see a lot more of his work here: https://www.wikiart.org/en/eugene-boudin There is also a much longer and detailed biography—in French—here: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eug%C3%A8ne_Boudin As you view his work, you can see why Monet claimed him as an early influence, as well as a dear friend.)

and “landscape”—as in this painting by John Constable (1776-1837)—

(And you can learn a bit more about Constable and see a small gallery of his works here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Constable )

but, in this posting, I want to talk about another –scape: soundscape, and, in particular, the soundscape I imagine inside the head of J.R.R. Tolkien.

We might begin where he began, with the tutoring of his mother, Mabel.

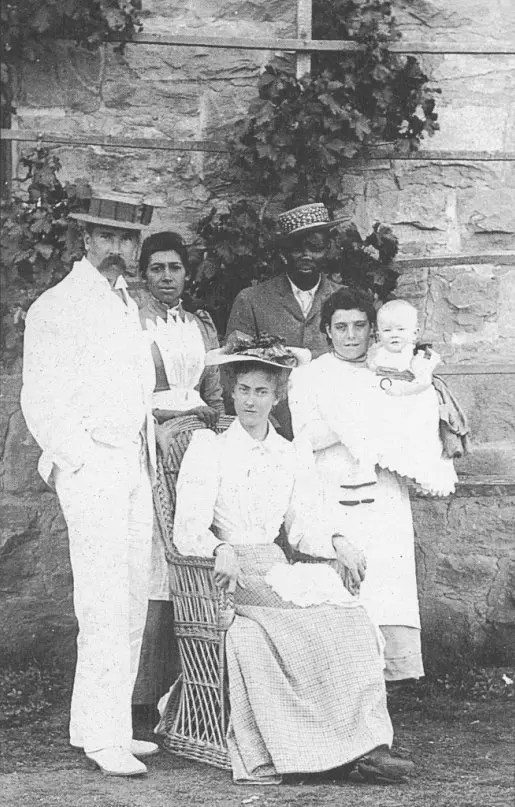

(Taken in Blomfontein, with Tolkien’s father on the left and a very tiny Tolkien on the right)

Carpenter’s biography tells us that Mabel

“…knew Latin…’

so we can imagine something like this in Tolkien’s ears:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BbcRm5EbGxg “Scorpio Martianus”

To which I’ll add:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mPuEO0VAh04 This is an attempt at Latin conversation and fun to listen to, but the subtitles don’t always mirror what is said and the use of “ius” instead of “lex” might be questioned for “law” in the script.

NativLang: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_enn7NIo-S0&t=44s This is a favorite language site of mine and this is entitled “What Latin Sounded Like and How We Know”.

“…French…”

Try this slowed-down version with subtitles—in both French and English—as I imagine that any French Mabel would have tried out would have been in talking to JRRT, then a small child, and would have been slow: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aMx0d42wzBs Unfortunately, in later life Tolkien would write: “For instance I dislike French..”—and he also rejected French cooking—see “From a letter to Deborah Webster”, 25 October, 1958, Letters, 411.

“…and German…” (Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien. 35)

This is actually German words/phrases at the children’s level (with German/English subtitles): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PSu7RN1IP5Q

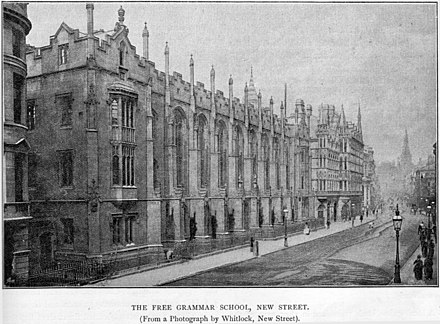

From Mabel, we can pass to more formal education, first at King Edward’s School in Birmingham.

Here, according to Carpenter, he was exposed to Greek:

“On his return to King Edward’s, Ronald was placed in the Sixth Class, about half way up the school. He was now learning Greek. Of his first contact with this language he later wrote: ‘The fluidity of Greek, punctuated by hardness, and with its surface glitter captivated me. But part of the attraction was antiquity and alien remoteness (from me): it did not touch home.’ “ (Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien. 35)

For ancient Greek, try: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NOJsnFz4Um0

This is closer to what we understand Greek to have sounded like, including turning Greek theta into the sound T + a tiny explosion of breath afterwards (as Greek phi would sound like P + that same explosion). There are a number of recitations on-line, but often strongly influenced by modern Greek, including the distinctive modern Greek pronunciation of sigma, which is a kind of hissy under-the-breath sound, which I like, but seems more modern than classical.

Even as he was increasing his knowledge of Latin and adding Greek to it through school instruction, Tolkien was making his own additions to what went on in his head.

Because his guardian, Father Francis Morgan (1857-1935)

spoke Spanish fluently and had a collection of books in Spanish, Tolkien was drawn to the language, later writing:

“…my guardian was half Spanish and in my early teens I used to pinch his books and try to learn it: the only Romance language that gives me the particular pleasure of which I am speaking…” (letter to W.H. Auden, 7 June, 1955, Letters, 312)

Here’s a little fun Spanish—this is Castilian, which is what I imagine Father Francis spoke, his family being from Andalusia: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ybfyLfI5Ml0 You can read more about Father Francis here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Xavier_Morgan )

We can add to this Anglo-Saxon (now commonly called Old English) at this time—and here’s a sample for you:

Beowulf: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CH-_GwoO4xI

and likewise Middle English, which you can hear here:

Chaucer, General Prologue: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qWM1Yk_BXMw

both thanks to an assistant master at King Edward’s, George Brewerton, who loaned Tolkien an Anglo-Saxon primer –my guess being Sweet’s—

(You can see what Brewerton’s loan looked like here: https://archive.org/details/anglosaxonprimer00sweerich )

and who:

“…encouraged his students to read Chaucer , and he recited the Canterbury Tales to them in the original Middle English.” (Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien, 35)

(Here, by the way, is an interesting comparison in the changing sounds of English over centuries: Old/Middle/Early Modern “The Lord’s Prayer”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nhgXnEGSn4A )

This isn’t all, however.

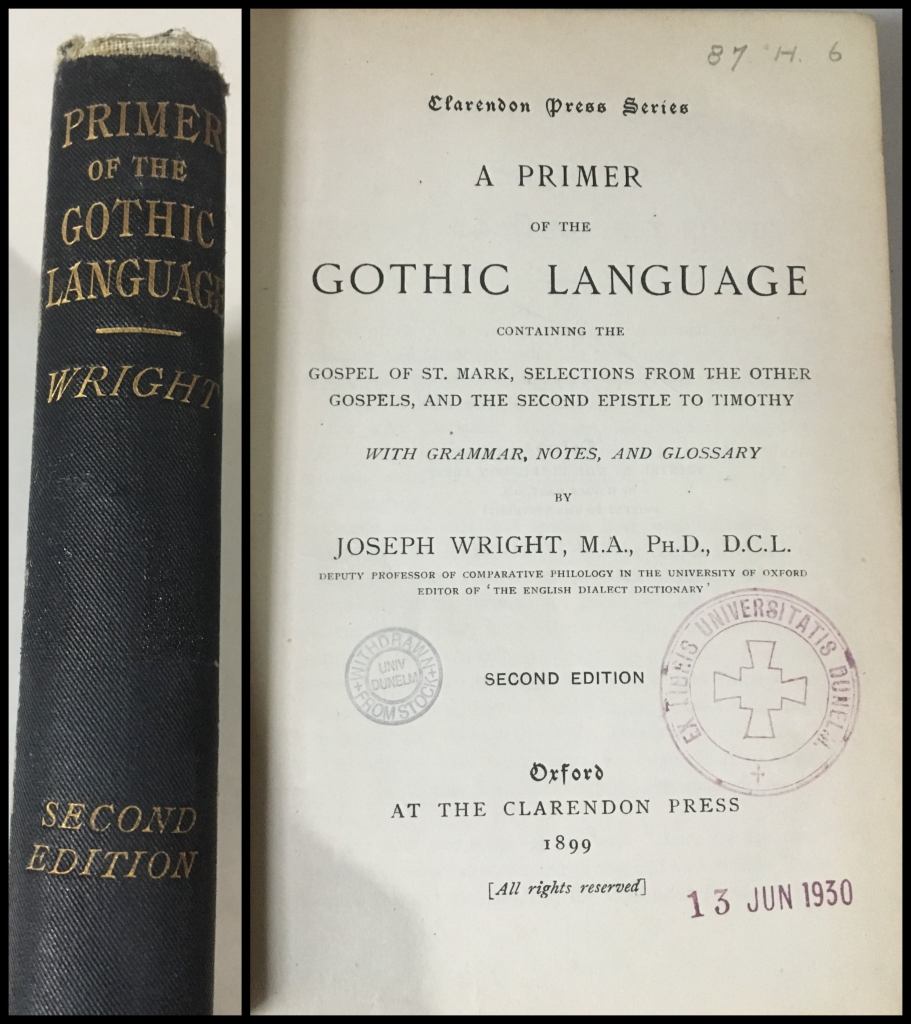

“One of his school-friends had bought a book at a missionary sale, but found that he had no use for it and sold it to Tolkien. It was Joseph Wright’s Primer of the Gothic Language. Tolkien opened it and immediately experienced ‘a sensation at least as full of delight as first looking into Chapman’s Homer. ‘ “ (Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien, 45)

(If you’d like to see what so pleased JRRT, see: https://archive.org/details/aprimergothicla00wriggoog )

Here’s a short possible reconstruction of what Gothic sounded like: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/GORwFe5TL5c

And more about Gothic here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l-pmudxHUfQ

To which we should add Old Norse:

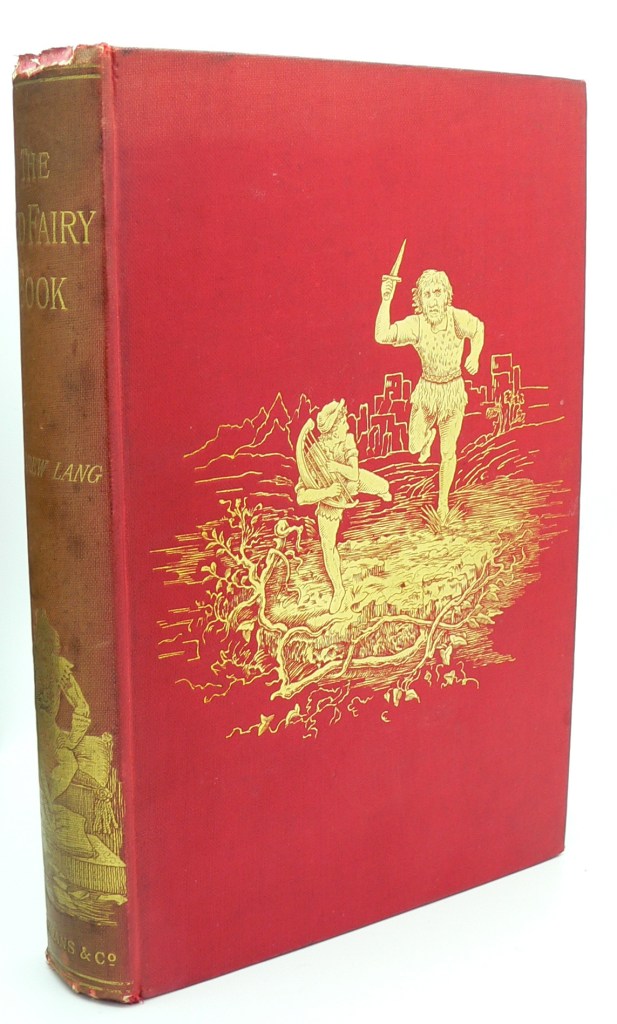

“Then he turned to a different language and took a few hesitant steps in Old Norse, reading line by line in the original words the story of Sigurd and the dragon Fafnir that had fascinated him in Andrew Lang’s Red Fairy Book when he was a small child.” (Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien, 43)

Here’s a brief selection : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ASsCH17cbA ( This is from Jackson Crawford’s very interesting Norse website. And you can read the Sigurd story which fascinated Tolkien here: https://archive.org/details/redfairybook00langiala/redfairybook00langiala/ Tolkien formalized and extended his study of Old Norse at Oxford—see Carpenter, 71-72. Old Norse is the ancestor of Icelandic and JRRT was particularly pleased when he was informed that The Hobbit was being translated into Icelandic. See “from a letter ot Ungfru Adalsteinsdottir”, 5 June, 1973, Letters, 603)

With all of this behind him, Tolkien went off to Oxford, to Exeter College,

intending to continue his classical studies, but then:

“I did not learn any Welsh till I was an undergraduate, and found in it an abiding linguistic-aesthetic satisfaction…”

and here you can hear some Welsh: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fvtbdq3WiyU

As a child, Tolkien’s eye had been caught by hopper cars labeled in Welsh full of coal from Welsh mines (Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien, 33-34),

but it was only at Exeter , encouraged by the man who had written the Gothic text which had been such a revelation, Joseph Wright (1855-1930), that

“He managed to find books of medieval Welsh, and he began to read the language that had fascinated him on coal-trucks. He was not disappointed; indeed he was confirmed in all his expectations of beauty.” (Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien, 64)

and then:

“ ‘Most important, perhaps, after Gothic was the discovery in Exeter College library, when I was supposed to be reading for Honour Mods, of a Finnish Grammar. It was like discovering a complete wine-cellar filled with bottles of an amazing wine of a kind and flavour never tasted before. It quite intoxicated me…’ ” (letter to W.H. Auden, 7 June, 1955, Letters, 312)

Here’s what Finnish sounds like: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r6xt8HZy1-k

(I have no current evidence for what Tolkien’s actual discovery might have been, but here’s an 1890 Finnish grammar that, being an Oxford University Press publication, might be a good possibility: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/59795/59795-h/59795-h.htm )

So, what might Tolkien have had echoing through his capacious head? German, French, Latin, Greek, Old and Middle English, Gothic, Spanish, Old Norse, Welsh, and Finnish—which I thought covered them all until I discovered:

“In hospital, besides working on his mythology and the elvish languages, he was teaching himself a little Russian and improving his Spanish and Italian.” (Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien, 106)

and:

“The Dutch edition and translation are going well. I have had to swot at Dutch; but it is not a really nice language. Actually I am at present immersed in Hebrew. If you want a beautiful but idiotic alphabet, and a language so difficult that it makes Latin (and even Greek) seem footling—but also glimpses into a past that makes Homer seem recent—then that is the stuff!” (letter to Michael George Tolkien, 24 April, 1957, Letters, 370)

As if German, French, Latin, Greek, Old and Middle English, Gothic ,Old Norse, Spanish, Italian, and a little Russian, Welsh, and Finnish—not to mention creating Sindarin, Quenya, a little of the language of the Dwarves, a bit of the tongue of the Ents, Rohirric, and even a fragment of the Black Speech–were not enough.

Thanks, as ever for reading.

Stay well,

Remember that: “To learn a language is to have one more window from which to look at the world.” (a Chinese proverb)

And remember, as well, that there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

As a contrast, here’s the sound of a language Tolkien didn’t care for (besides French)–see “From a letter to Deborah Webster”, 25 October, 1958, Letters, 412–https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vfXBjv-uMZM