Tags

Agincourt, anti-aircraft gun, Archery, Arthur Machen, Bard, Bilbo, black arrow, Crecy, Dwarves, Fafnir, Fantasy, Howard Pyle, James Fenimore Cooper, Le Cateau, NC Wyeth, Poitiers, Robert Louis Stevenson, Robin Hood, Sigurd, Smaug, The Bowmen, The Hobbit, Tolkien

Welcome, as ever, dear readers,

When Bilbo and the dwarves

(the Hildebrandts)

set out on their quest, they’re aware that, at its end, they must face the reason the dwarves’ forebears died or fled Erebor, the “Lonely Mountain”.

(JRRT)

And yet they go, suggesting an almost foolhardy shrug of an attitude, particularly as Gandalf has suggested that they need someone right out of myth to help them:

“ ‘That would be no good…not without a mighty Warrior, even a Hero.’ “

But:

“ ‘I tried to find one; but warriors are busy fighting one another in distant lands, and in this neighbourhood heroes are scarce, or simply not to be found.’ “ (The Hobbit, Chapter 1, “An Unexpected Party”)

Everything about this trip already seems haphazard, having no map of their destination, till Gandalf furnishes them with one,

(JRRT)

and even then they have no idea of another, secret entrance until Elrond spots the inscription which describes it—and how to open it. Clearly, then, this is a case of “we’ll cross that bridge when we come to it.”

Uh oh.

There’s also no clue in the text as to who or what may destroy the destroyer—until Bilbo, flattering Smaug, spots that fatal weak point:

“ ‘I’ve always understood…that dragons were softer underneath, especially in the region of the—er—chest…’ “

The dragon stopped short in his boasting. ‘Your information is antiquated,’ he snapped. ‘I am armoured above and below with iron scales and hard gems. No blade can pierce me.’ “

There’s a clue here, if not for Bilbo, for readers who are aware of something in Tolkien’s own past reading:

“Then Sigurd went down into that deep place, and dug many pits

in it, and in one of the pits he lay hidden with his sword drawn.

There he waited, and presently the earth began to shake with the

weight of the Dragon as he crawled to the water. And a cloud of

venom flew before him as he snorted and roared, so that it would

have been death to stand before him.

But Sigurd waited till half of him had crawled over the pit, and

then he thrust the sword Gram right into his very heart.” (Andrew Lang, ed., The Red Fairy Book, 1890, “The Story of Sigurd”, page 360)

And Bilbo persists, goading Smaug to turn over, where Bilbo sees—and says:

“ ‘Old fool! Why, there is a large patch in the hollow of his left breast as bare as a snail out of its shell!’ “ (The Hobbit, Chapter 12, “Inside Information”)

Still, although we might have a target now, who will make use of it and how and with what? Sigurd is just what Gandalf says is not locally available, a Hero, and it’s clear that neither Bilbo nor the dwarves are capable of taking on that role.

And here we can bring in another clue from Tolkien’s past.

In “On Fairy-Stories”, he writes:

“I had very little desire to look for buried treasure or to fight pirates, and Treasure Island left me cool. Red Indians were better: there were bows and arrows (I had and have a wholly unsatisfied desire to shoot well with a bow)…” (“On Fairy Stories”, 134)

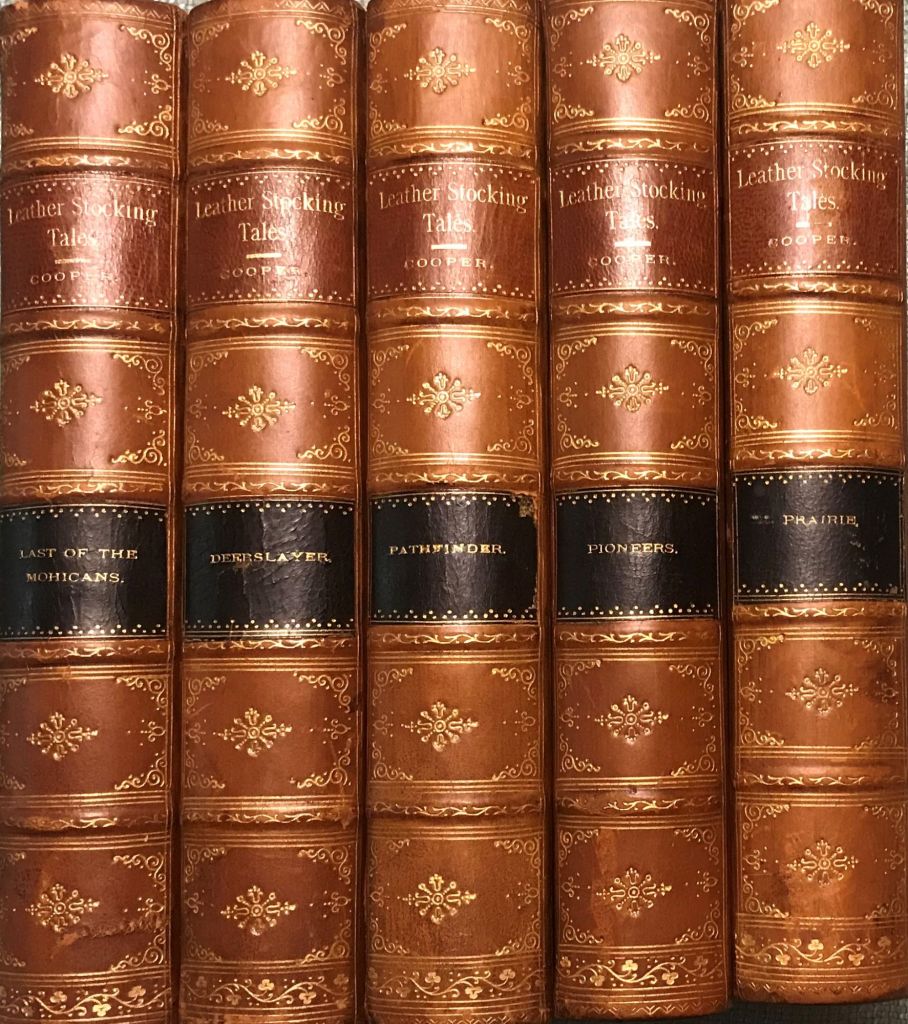

This suggests that Tolkien may have been exposed to the works of James Fenimore Cooper, 1789-1851, who, beginning with The Pioneers, 1823, wrote a series of novels set on the 18th-century western Frontier (much of it what is now central and eastern New York State), called the “Leatherstocking Tales”,

the best known, even now, being The Last of the Mohegans, 1826.

These books were filled with battles between the British and French, with Native Americans on both sides and I wonder if it’s from the adventures depicted there that JRRT was inspired with his passion for bows and arrows?

(artist? A handsome depiction and I wish I could identify the painter.)

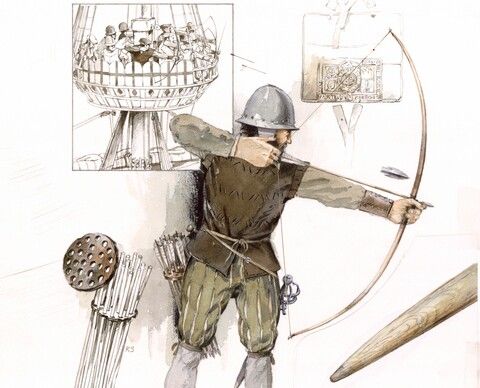

Another clue might lie in British history. During the medieval struggle for English control of France, the so-called “Hundred Years War” (1337-1453), the English enjoyed three great victories, at Crecy (1346), Poitiers (1356), and Agincourt (1415), where companies of English longbowmen shot their French opponents to pieces.

(Angus McBride)

Tolkien would have read about this as a schoolboy, but, in an odd way, he might have had his knowledge of these long-ago events refreshed in 1914.

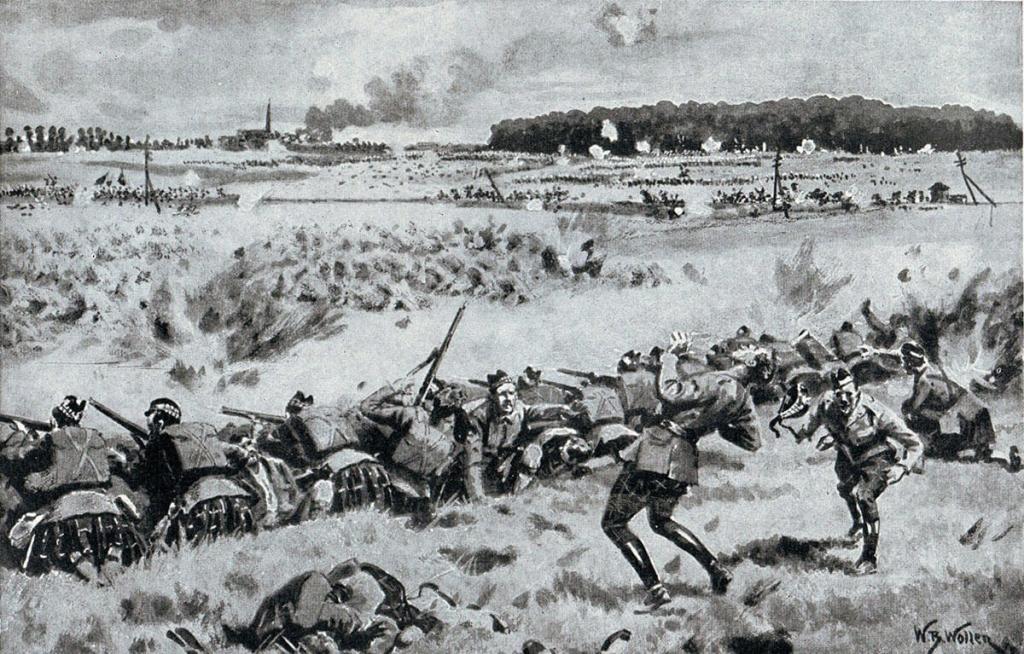

Outnumbered and in danger of being outflanked by massive German columns, the small BEF (British Expeditionary Force), in the early fall of 1914, retreated, one unit (2nd Corps) fighting a desperate battle to slow the Germans at Le Cateau.

The British managed to fend off the enveloping Germans and, considering the odds against them, some might have believed their escape miraculous.

Enter the fantasist Arthur Machen, 1863-1947.

In the September 29th, 1914, issue of The Evening News, Machen published a short story which he entitled “The Bowmen”. This was a supposed first-hand account of a British soldier who had seen a line of ghostly British longbowmen shooting down German pursuers, just as they had shot down the French, centuries before.

Machen subsequently republished it with other stories in 1915—

but was astonished when his fiction was believed to have been true, and widely circulated as such. We don’t have any evidence that JRRT actually read this story, but it was extremely widespread at the time and, once more, we see men with bows. (For more on this, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angels_of_Mons And you can read the stories in Machen’s volume here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angels_of_Mons )

I think we can add to this the legends of Robin Hood, which could appear in any number of sources—our first known reference being in William Langland’s (c.1330-c.1386) late 14th-century Piers Plowman, where Sloth—a priest deserving of his name, doesn’t seem to have any religious knowledge, but says,

“Ich can rymes of Robyn Hode” (that is, “I know rhymes/songs about Robin Hood”—see the citation at: https://robinhoodlegend.com/piers-plowman/ at the impressively rich Robin Hood site: https://robinhoodlegend.com/ )

Then there is the collection of poems/songs from about 1500, A Gest of Robyn Hode,

which JRRT might have encountered in F.J. Child’s (1825-1896) The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, 1882-1898,

where it appears as #117. (If you don’t know the so-called “Child Ballads”, here’s a beginning: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Child_Ballads And, for a massive one-volume edition: https://archive.org/details/englishscottishp1904chil/page/n11/mode/2up The texts are interesting in themselves, but, for me, they’re even better as songs. To hear one, you might try one of my favorite folk singers, Ewan McColl’s version of “The Dowie Dens o’ Yarrow here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vfsv8zUdqKM&list=RDVfsv8zUdqKM&start_radio=1 For more on Yarrow, see “Yarrow”, 10 April, 2024.

For lots more on Robin Hood, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robin_Hood )

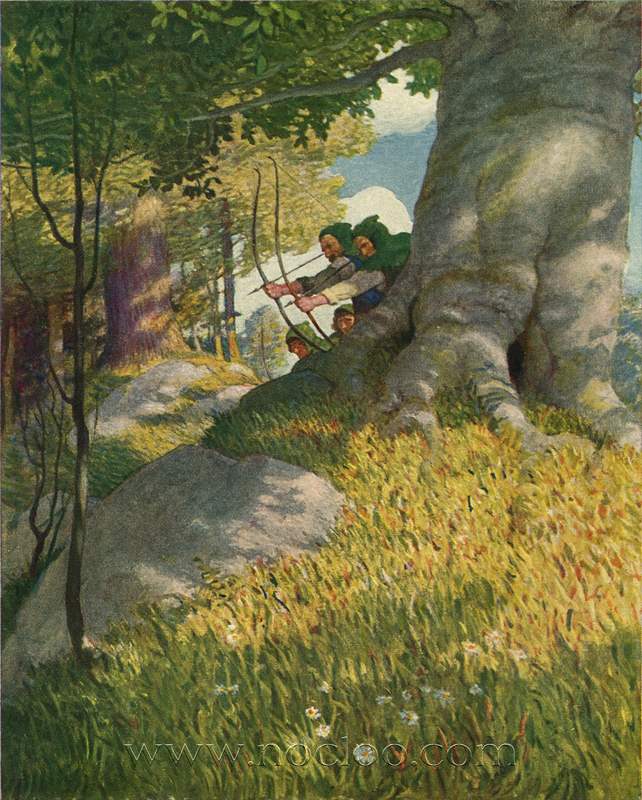

In more recent times, perhaps Tolkien had seen Howard Pyle’s (1853-1911) The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, 1883,

or Paul Creswick’s (1866-1947) 1917 Robin Hood,

with its wonderful illustrations by N.C.Wyeth (1882-1945).

(If the Tolkien journal Amon Hen, is available to you–but, alas, not to me–you might also have a look at Alex Voglino’s “Middle-earth and the Legend of Robin Hood” in issue 284.)

And, although Tolkien may not have liked Treasure Island, we might add to this possible influence Robert Louis Stevenson’s (1850-1894) The Black Arrow (serialized 1883, published as a book in 1888).

An adventure story set during the Wars of the Roses, you can read it here: https://archive.org/details/blackarrowatale02stevgoog/page/n1/mode/2up

Although there are more possibilities (Tolkien might have read Sir Walter Scott’s (1771-1832) Ivanhoe, 1819, where Robin Hood makes an appearance, for instance—and here’s the book: https://archive.org/details/ivanhoe-sir-walter-scott/page/n7/mode/2up )

that title suggests something else:

“ ‘Arrow!’ said the bowman. ‘Black arrow! I have saved you to the last. You have never failed me and always I have recovered you. I had you from my father and he from of old. If ever you came from the forges of the true king under the Mountain, go now and speed well!’ “ (The Hobbit, Chapter 14, “Fire and Water”)

(Michael Hague, one of my favorite Hobbit illustrators)

So, we’re about to see that the Hero to kill Smaug is a Lake-town local, Bard, and his weapon of choice is Tolkien’s special favorite, the bow. But how to attack?

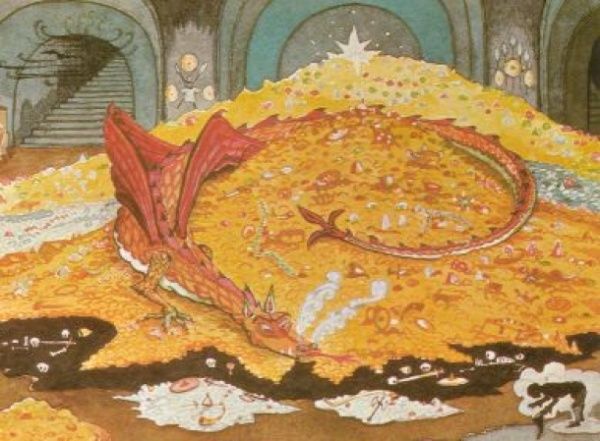

We first see Smaug on the ground, lying on his hoard.

(JRRT)

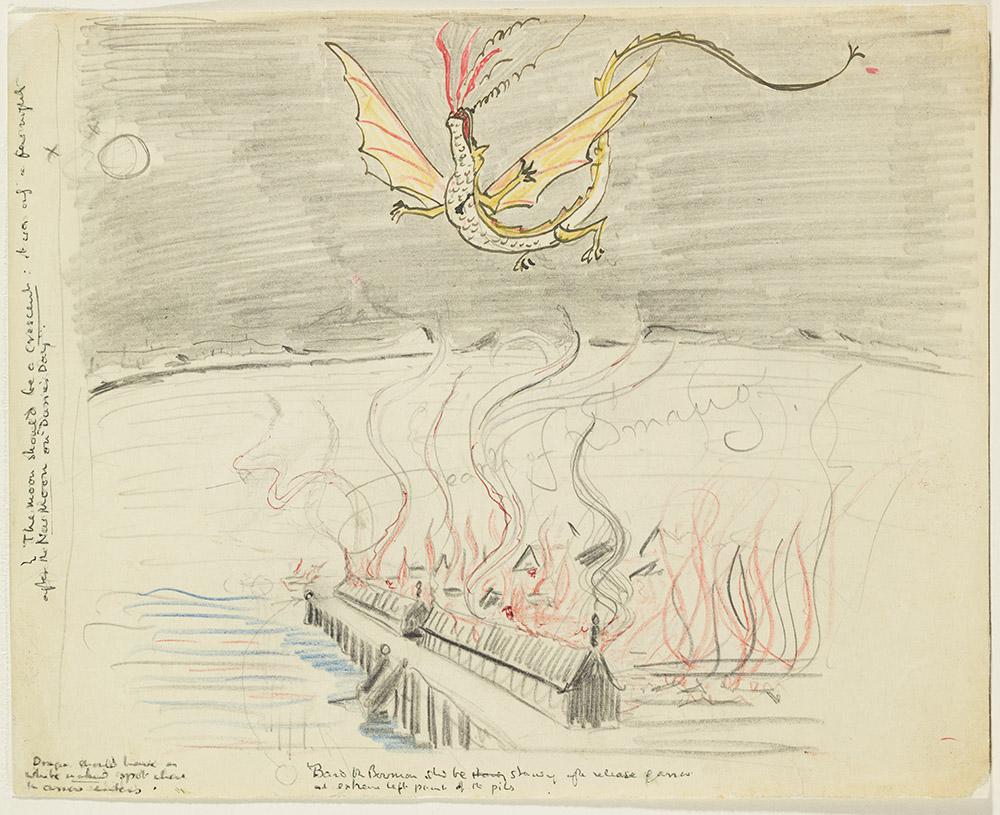

Angered at Bilbo’s teasing, he gets up long enough to attempt to flame him, but his real method of destruction is to take to the air.

(Ted Nasmith)

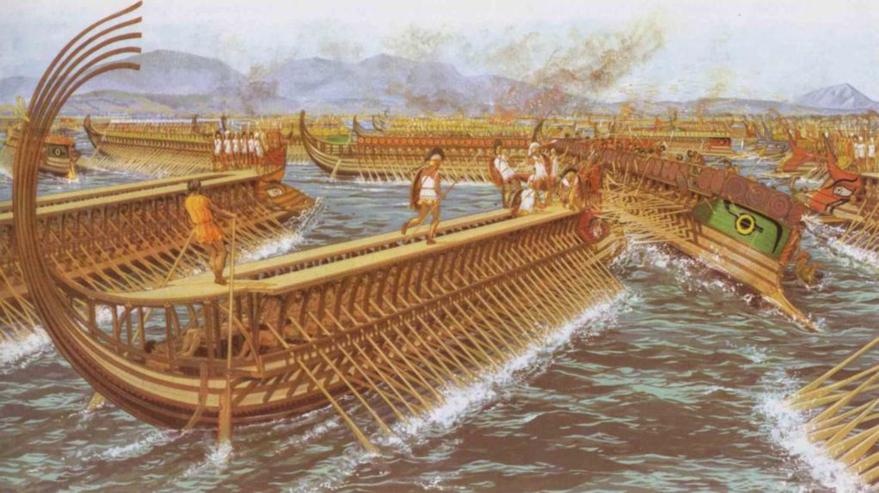

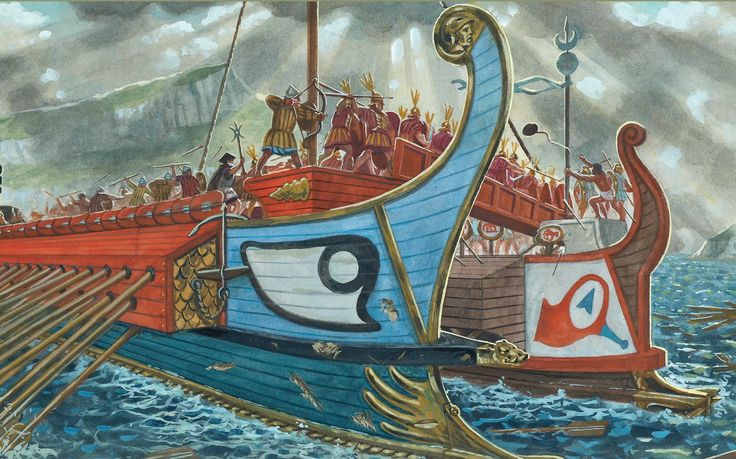

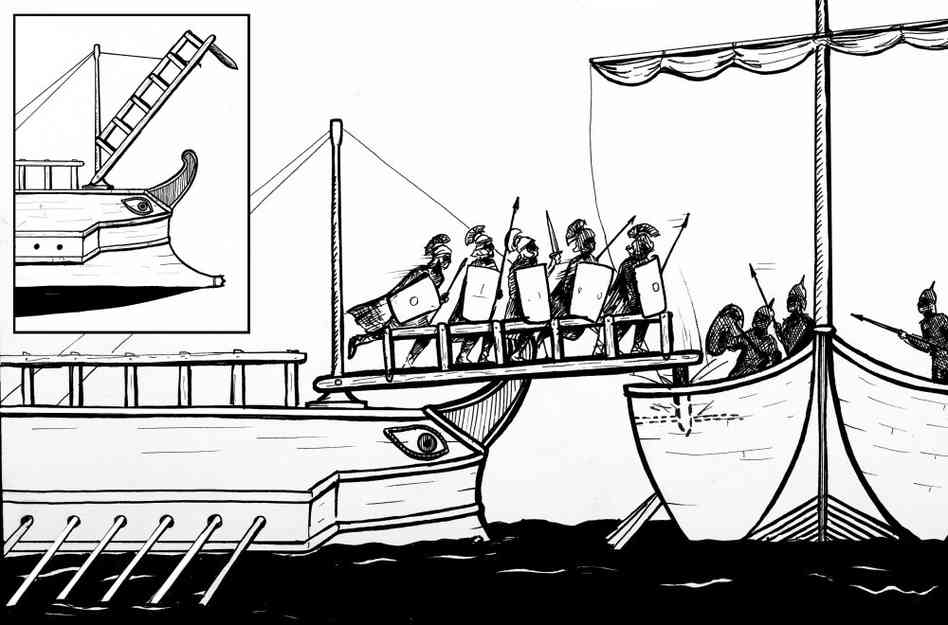

Fafnir was never airborne, dragging himself along the ground. Sigurd solved the problem of his scaly protection by digging a pit and attacking him from below with his sword. It makes good sense, then, with all of the possible bowman influences upon him, that Tolkien would imagine that the way to deal with a flying dragon would be an arrow from below.

(JRRT)

To which we might add one more potential influence from JRRT’s own experience.

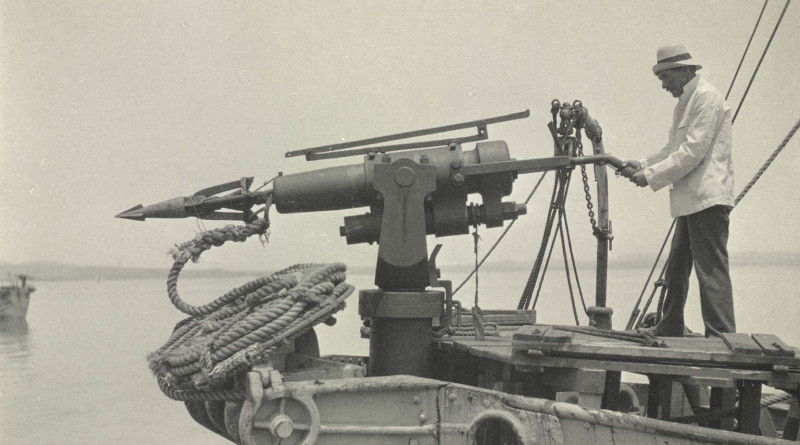

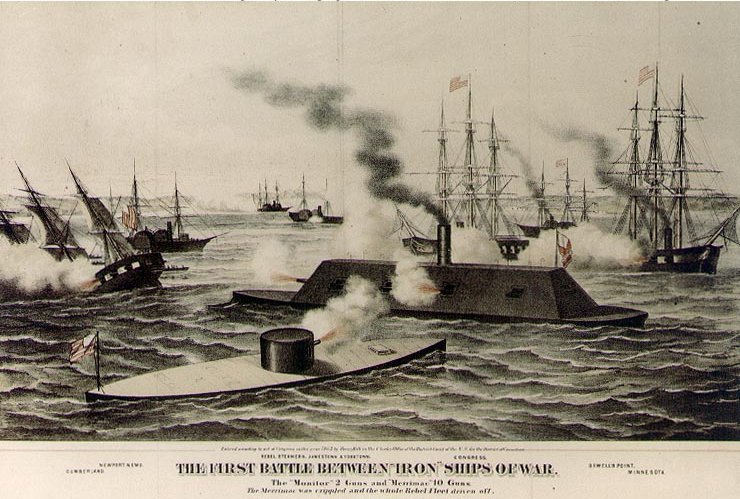

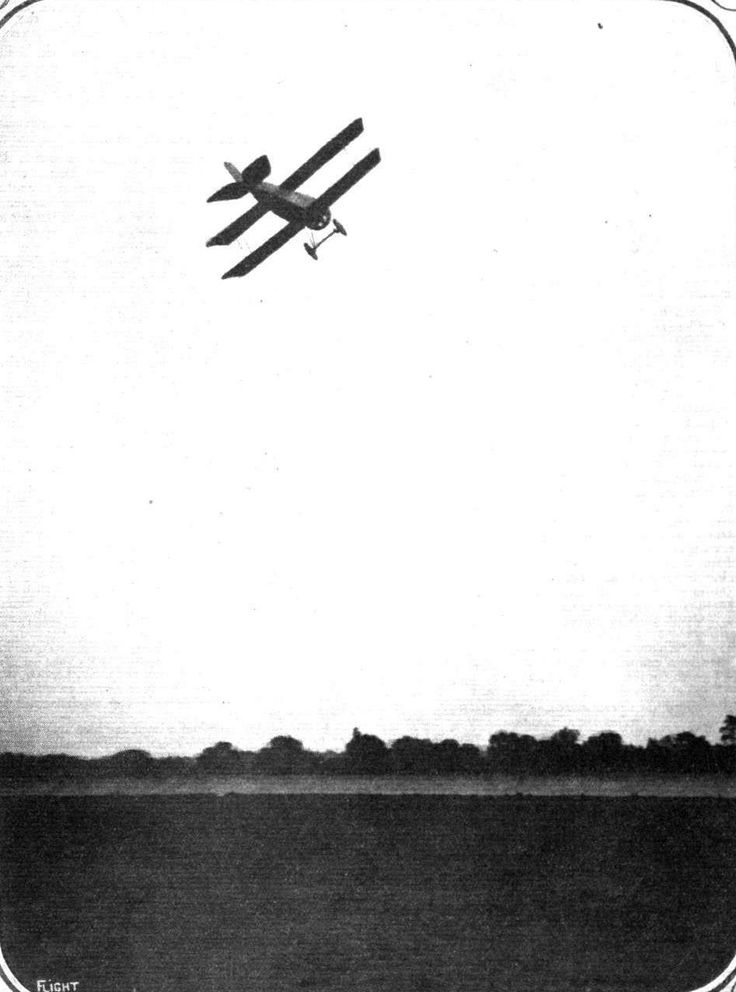

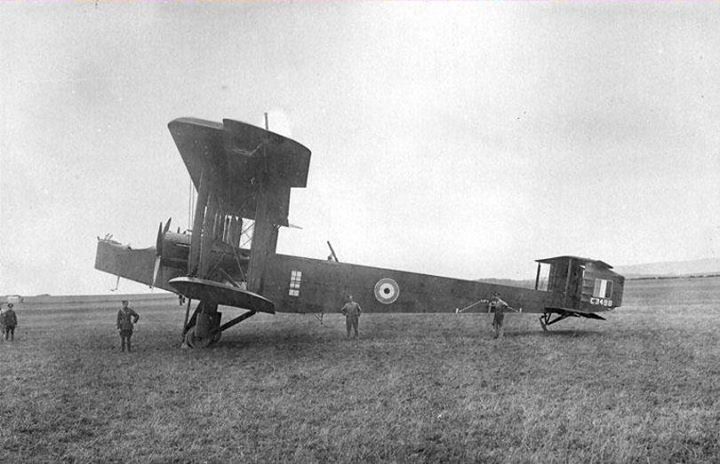

In 1914, there were few military aircraft and their main task was reconnaissance.

By 1918, there were many different models, with different tasks, including heavy bombers.

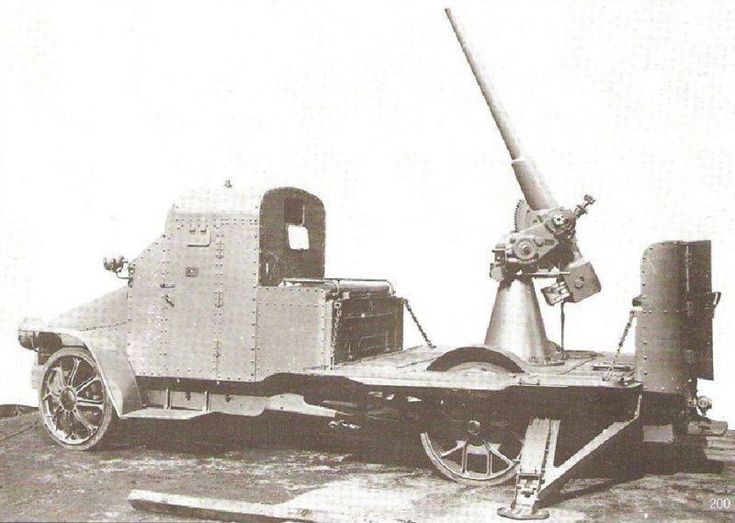

To protect their troops on the ground, all of the warring nations developed the first artillery defenses: anti-aircraft guns, designed to shoot down threats from above.

JRRT would certainly have seen such guns and possibly even in action, attempting to knock flying danger out of the sky.

Some of those guns were rapid-firing, spraying the air with metal, hoping to guarantee the success of their defense. Bard, in turn, has his black arrow—and not just any black arrow, but one seemingly created perfectly for revenge: “ ‘I had you from my father and he from of old. If ever you came from the forges of the true king under the Mountain, go now and speed well.’ “

That is, this is an arrow created by the dwarves, whom Smaug had driven out or killed—or eaten—and it’s also an heirloom from the days before Smaug destroyed Dale: what better weapon to deal vengeance to the wicked creature who had ruined so much? To take out such a flying danger, but with a glaring vulnerability below, what means of propulsion, especially one known to have defeated whole medieval armies? And, as the seemingly last descendant of the last lord of Dale, Girion, who better to take that revenge?

As ever, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

Always monitor the skies—who knows what’s watching from above?

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

For more on birds, Bard, and Smaug, see “Why a Dragon?” 28 May, 2025.

PPS

While looking for just the right Smaug images, I came upon this, entitled, “Dante aka Smaug on his hoard” and couldn’t resist.