Welcome, as ever, dear readers.

Perhaps you’ve heard someone—often, I would say, an older person—who, confronted with something electronic, will say, “I’m not a Luddite, but…”

It’s taken to mean “I’m not against technology, but…”

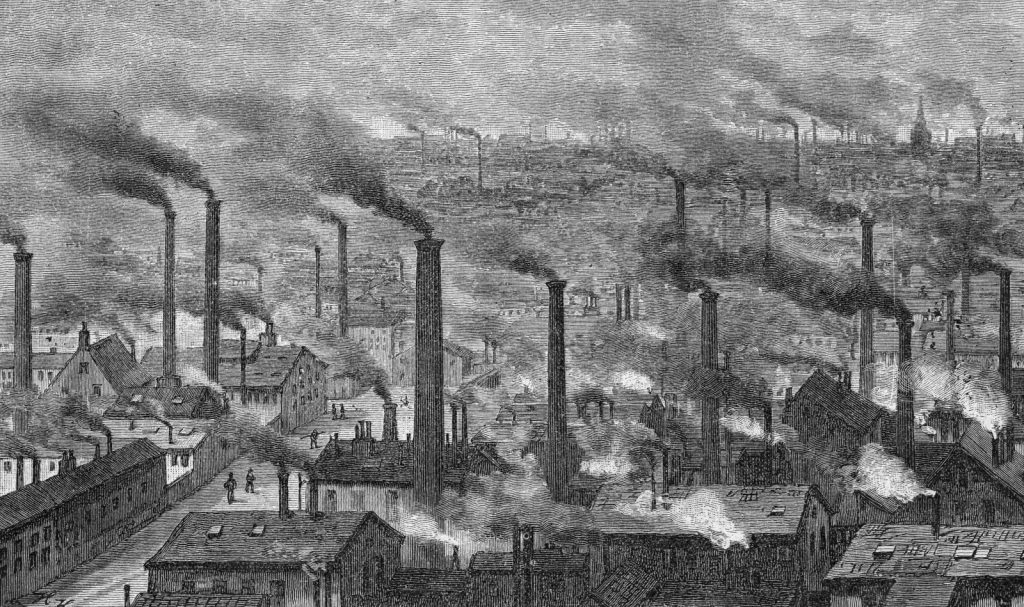

But the history of the word casts a shadow on that disclaimer, as the real Luddites were very much against technology—technology which put them out of work and set them and their families to starve—or to be worked to death in the new factories. (Charles Dickens captures a little of this in Hard Times, 1854: https://archive.org/details/hardtimes0000char_w0u2/page/n11/mode/2up )

It all began with wool.

Wool production had made certain elements of medieval England very rich.

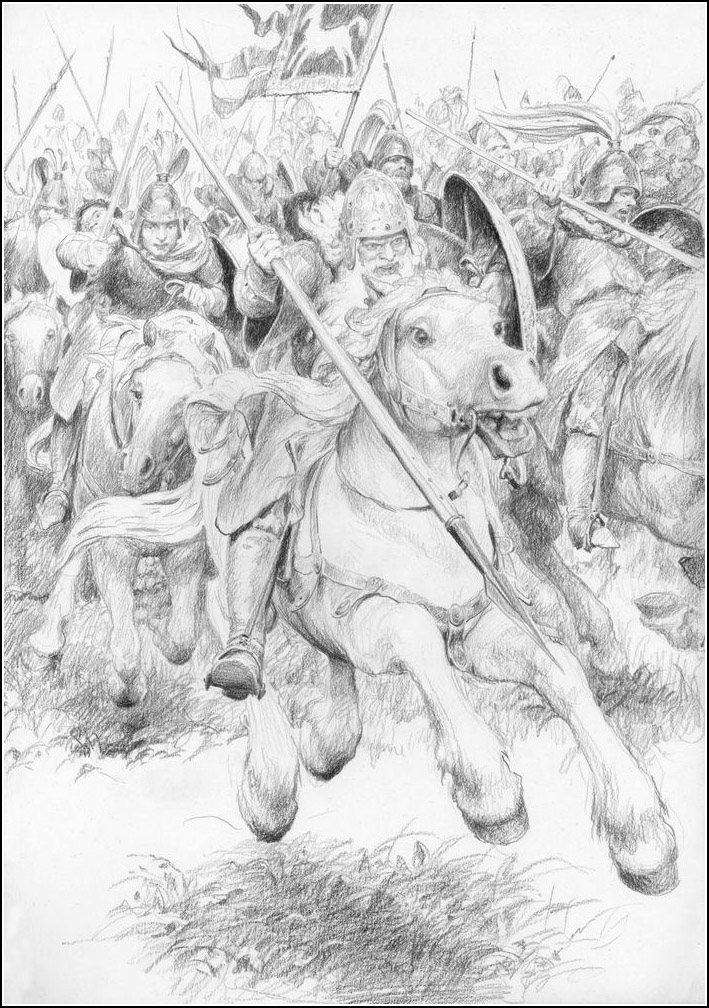

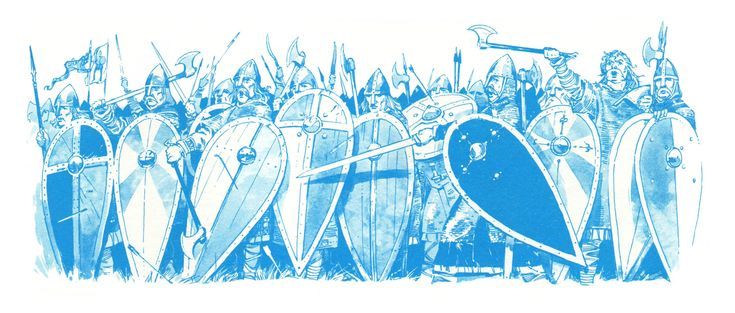

At the same time, because it was such a labor-intensive industry, it kept many ordinary people employed in everything from raising sheep to sheering, washing, carding, spinning, and weaving, almost all of which you can see in this illustration.

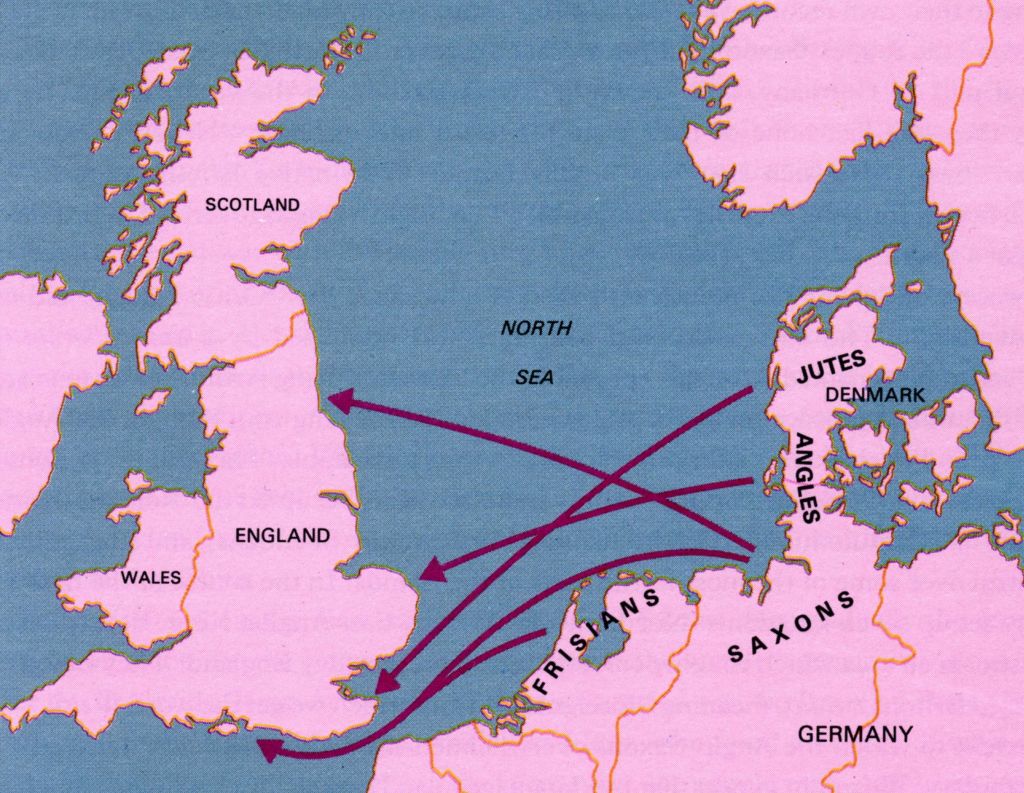

The demand for more and more wool and wool products in the later 18th century brought about the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, when clever men began to invent devices which sped up the originally slow process of wool production, creating machines and then factories.

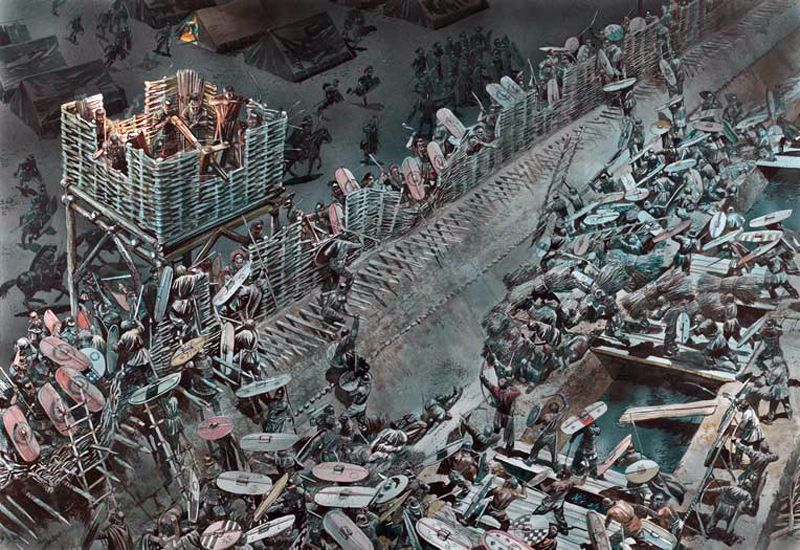

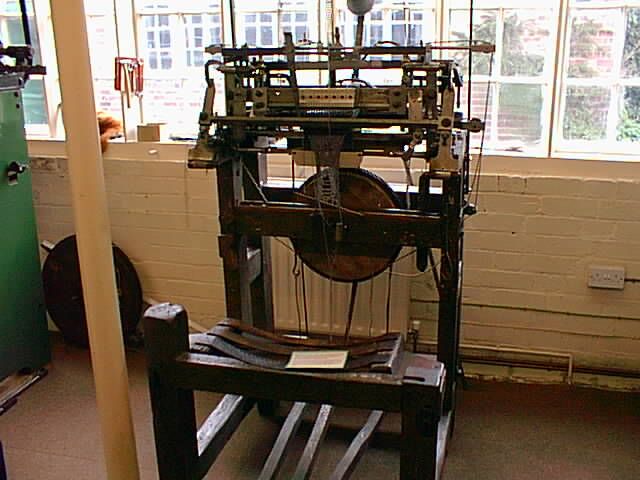

(This is a room in Quarry Bank, a wool mill complex in Cheshire, just a few miles from where Tolkien grew up, in Manchester. It is held by the National Trust and, if like me, you’re interested in the history of the Industrial Revolution, you’ll want to learn more at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quarry_Bank_Mill )

Such places not only sped up production, but also cut down on the number of people needed to process the wool, which soon began to trouble the many who once lived by the old methods.

As early as 1768, there had been attacks on machines and the name “Ludd” had originally been attached to an apprentice, “Ned Ludd”, who had supposedly smashed two knitting machines, called “stocking frames” in 1779.

In 1811, things had reached a stage where organized violence against machines, factories, and even factory-owners, increased and “King Ludd” or “General Ludd” became a kind of meme for the anti-industrial movement. (You can read more here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luddite )

This imaginary Ludd is, however, only one of a number of figures under that name. There is, for instance, the Biblical Lud, the son of Shem, the son of Noah.

(from the wonderful mosaics of Monreale, in Sicily—Noah, we’re told, got drunk and his embarrassed sons are covering him up—see Genesis 9.20-23 for details)

There is Lud, son of Heli, and king of Britain, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth’s 12th century Historia Regum Britanniae, the founder of London, and buried at Ludgate, of course. (You can read, in a 1904 translation, about Lud in Historia 3.20 here: https://archive.org/details/geoffreyofmonmou00geofuoft/geoffreyofmonmou00geofuoft/page/80/mode/2up

(as reconstructed in 1895—you can read more about the site here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ludgate including the actual etymology of the name)

And then there’s Lud-in-the-Mist, a 1926 fantasy novel

by Hope Mirrlees (1887-1978),

where Lud is the name of a town in the imaginary country of Dorimare.

(Ryuk-Duck, but, when I’ve gone to DeviantArt, I’ve been unable to locate anything more.)

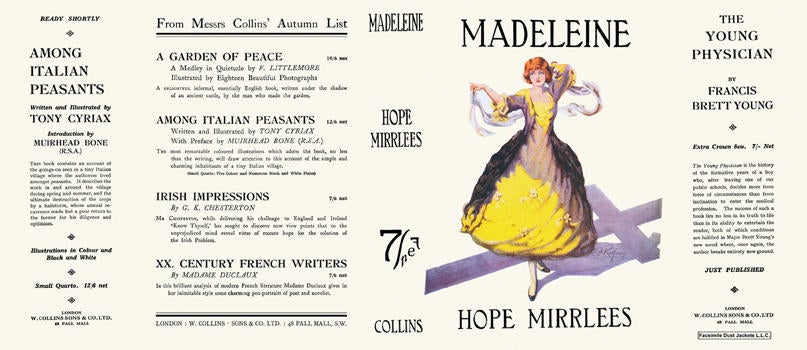

Mirrlees had published two previous novels, Madeleine: One of Love’s Jansenists (1919)

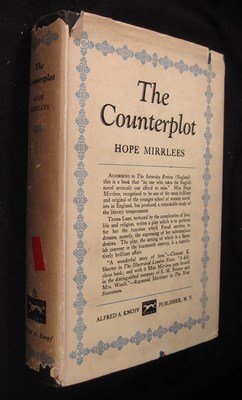

and The Counterplot (1924),

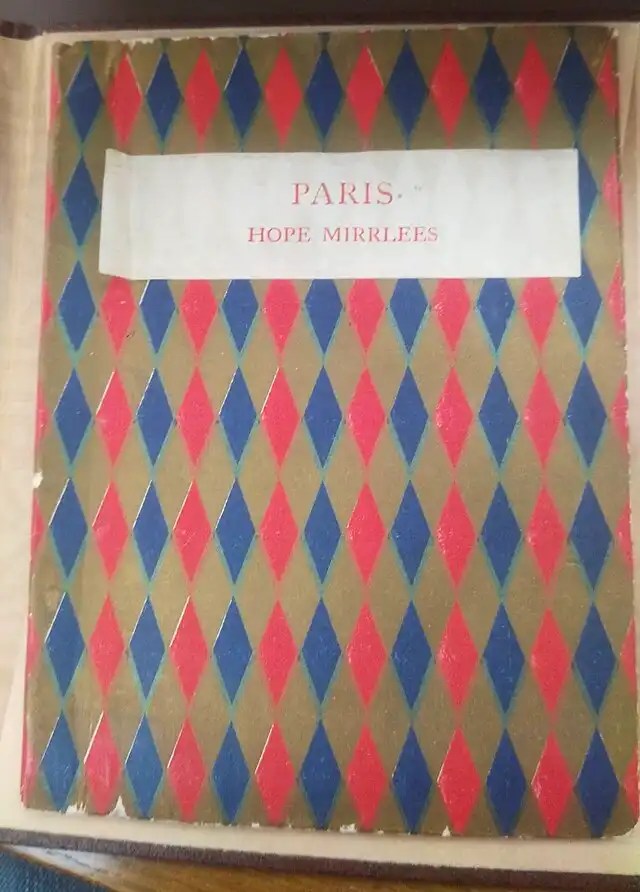

as well as a rather complex “modernist” poem, Paris (1920),

but this was her only fantasy novel.

(You can read all four of these four works here: Madeleine https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/65926/pg65926-images.html Paris https://www.paris-a-poem.com/ —this is, by the way, a real work of scholarship and a very useful way to approach this poem—The Counterplot https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/63935/pg63935-images.html and Lud-in-the-Mist https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/68061/pg68061-images.html You can read more about the author here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hope_Mirrlees )

I’ve just finished Lud-in-the-Mist, which, after disappearing for about 50 years, resurfaced in a first reprint in 1970, and several more, in 2000, 2005, and 2013. The 2005 reprint had very distinguished opening matter: a foreward by Neil Gaiman and an introduction by Douglas Anderson, of The Annotated Hobbit. Gaiman has said of Lud-in-the-Mist that it’s “My favourite fairy tale/detective novel/history/fantasy” (quoted from: https://radicalreads.com/neil-gaiman-favorite-books/ ) and I would agree that it’s a combination at least of fairy tale and fantasy and there is a sort of detective story mixed in, but I’m not so sure that this all comes together for me as it clearly has for him.

The fantasy/fairy tale lies in the basic setting that: Dorimare is an imaginary country and Lud-in-the-Mist is its capital, sitting at the meeting of two rivers: Dapple and Dawl. The Dawl seems to be the usual, expected kind of river, flowing southwards to the sea from somewhere inland, but the Dapple

“…had its source in Fairyland (from a salt inland sea, the geographers held) and flowed subterraneously under the Debatable Hills, was a humble little stream, and played no part in the commercial life of the town. But an old maxim of Dorimare bade one never forget that ‘The Dapple flows into the Dawl.’ It had come to be employed when one wanted to show the inadvisability of despising the services of humble agents; but, possibly, it had originally another application.”

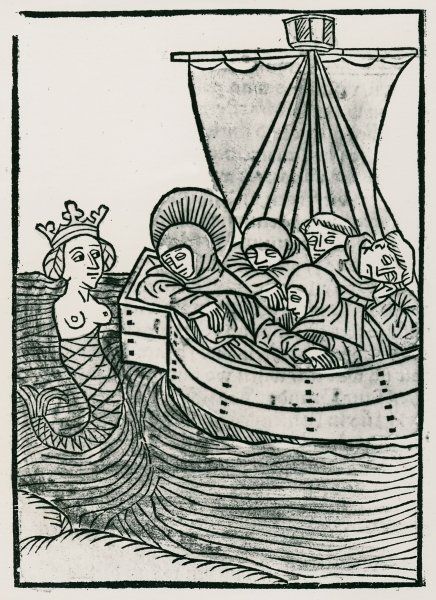

This is at the very beginning of the second chapter, and already sets the tone: Dorimare may be a picturesque little country on a river so broad that the town is also a seaport, although 20 miles from the actual sea, but that broad river is fed, in part, by a second stream, one which comes from the west (and the West, of course, is always a place perhaps to be dreaded, as it is often the direction to which the dead go in many folk traditions, as well as being the home of weird, otherworldly folk, the sort of people and creatures that voyagers west, like St Brendan

and Oisin, of the Irish Fenian Cycle, and Yeats’ early The Wanderings of Usheen, 1889, which you can read here: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/38877/38877-h/38877-h.htm#THE_WANDERINGS_OF_USHEEN encounter. ) The river’s beginning lies, as well, in a place not visited by the Dorimarites for hundreds of years, Fairyland, and much of the book is taken up with “fairy fruit”, which is banned in Dorimare, along with any dealings or even mentions of fairies, but somehow keeps appearing and seriously disturbing the minds of those who consume it—as if the Dapple, under its pretty name, is actually underflowing and perhaps undercutting all of Dorimare.

The detective story seems almost a by-blow of the plot, although it involves a major character, Endymion Leer, who is a physician in Lud-in-the-Mist and, as the plot develops, much more, although I find that his role in the mystery somewhat trivializes the greater role he claims for himself near the end of the book at his trial for murder.

I won’t summarize the complicated plot—you can read a brief and, I fear, inadequate précis here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lud-in-the-Mist and there are longer summaries to be had at various fantasy sites, although I find the ones I read, for me, too intent upon constructing complex, deeper meanings than I think the book really holds.

Instead, as I always do with reviews—films and books—I would encourage you to read it for yourself and come to your own conclusion.

There’s dry, quirky humor on the part of the narrator, some lush nature writing, a vivid depiction of what Fairyland might be like (unpleasant to nightmarish, I found it), and an appealing character in the protagonist, Nathaniel Chanticleer, who begins conventionally as a comfortable petit bourgeois (although he does have something haunting him), but grows into a feeling being through the fate of his son, Ranulph, all of which are at least enough to lure you in and perhaps keep you reading, as they did me.

So, as always, thanks for reading,

Wonder what fairy fruit might do to you,

And remember that, as ever, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

If going west myself, I should meet Hope Mirrlees, I would request that, should she, in some spiritual form, ever do a revised edition, she might include a map—a nice end paper one would do—as it would definitely help to keep one oriented in the characters’ travels around Dorimare.

PPS

For a powerful speech by Neil Gaiman on writing and reading and fantasy see: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/oct/15/neil-gaiman-future-libraries-reading-daydreaming