Welcome, as always, dear readers.

From his letters, it’s clear that Tolkien had very mixed feelings about Christmas.

To his son, Christopher, far away in the RAF, he writes:

“Today is the ‘last day for posting in time for Christmas’, and though I resent the way in which this feast of peace and joy is made into a labour (not to say a nightmare of shabby commercialism)…”

and continues:

“…The shops, by the way, pass belief here this year. There is stuff that a barbarian would be ashamed of, bits of shapeless wood and paper smeared with paint, and would certainly not be such fools as to purchase, selling for idiotic prices like 18/6 [18 shillings, 6 pence, when 1 shilling, 3 pence would buy a quart of milk—see: https://www.sunnyavenue.co.uk/insight/how-much-is-a-shilling-worth-today ). Surely this Xmas Gift business is a form of dementia, when it allows itself to be cheated so transparently.” (letter to Christopher Tolkien, 10 December, 1944, Letters, 149-150)

He has, however, already qualified this a bit by calling Christmas a “feast of peace and joy”, with a further proviso some years later in a letter to his son Michael:

“Well here comes Christmas! That astonishing thing that no ‘commercialism’ can in fact defile—unless you let it.” (letter to Michael Tolkien, 19 December, 1962, Letters, 457)

I have no idea what “bits of shapeless wood and paper smeared with paint” might actually be, but, as Tolkien has clearly been shopping and there are children in the family, I imagine that it was some crude, mass-produced toy, which might also suffer from wartime shortages of raw materials. Perhaps something like this?

Born in 1893, Tolkien had grown up in a world of increasingly-sophisticated children’s playthings, from Marklin’s beautifully-engineered toy trains

to William Britain’s popular toy soldiers

for boys and elaborate dolls,

elegant tea sets,

and doll houses for girls, among other toys.

As one of two sons of a mother barely scraping by,

it’s unlikely that he, or his younger brother, Hilary, could ever have more than glimpsed such things in a toy shop window,

and had to be contented with the lesser toys of the age—clay rather than stone marbles,

a wooden hoop, rather than a steel one,

or, in a moment of splurging on his mother’s part, perhaps a pop gun—one is mentioned in The Hobbit where, in Chapter 1, Gandalf refers to Bilbo opening his door like one—for more on that and other such weapons in fiction, see “Pop!” 13 December, 2017 here: https://doubtfulsea.com//?s=popgun&search=Go

In the Third Age of Middle-earth, we might expect to be surprised and puzzled by Gandalf’s remark, as there are no guns to be seen there and here we can’t use the plausible explanation for other anachronisms in the text, that it’s the narrator telling the story in the 1930s, as it’s Gandalf who says it, not the exterior—and much more modern—narrator.

But I would suggest another explanation—which also appears in The Hobbit. Speaking of the long-lost world of the dwarves’ Lonely Mountain and the town of Dale at its foot, Thorin says:

“Altogether those were good days for us, and the poorest of us had money to spend, and to lend, and leisure to make beautiful things just for the fun of it, not to speak of the most marvelous and magical toys, the like of which is not to be found in the world now-a-days. So my grandfather’s halls became full of armour and jewels and carvings and cups, and the toy market of Dale was the wonder of the North.” (The Hobbit, Chapter One, “An Unexpected Party”)

Perhaps, even before the appearance of gunpowder weapons (foreshadowed both by Saruman’s attack on Helm’s Deep and Sauron’s on the Causeway Forts in The Lord of the Rings), then, the dwarvish and human craftsmen of the region had created something which, in their time, used air to propel its missile, rather than this?

But what about other “most marvelous and magical” toys?

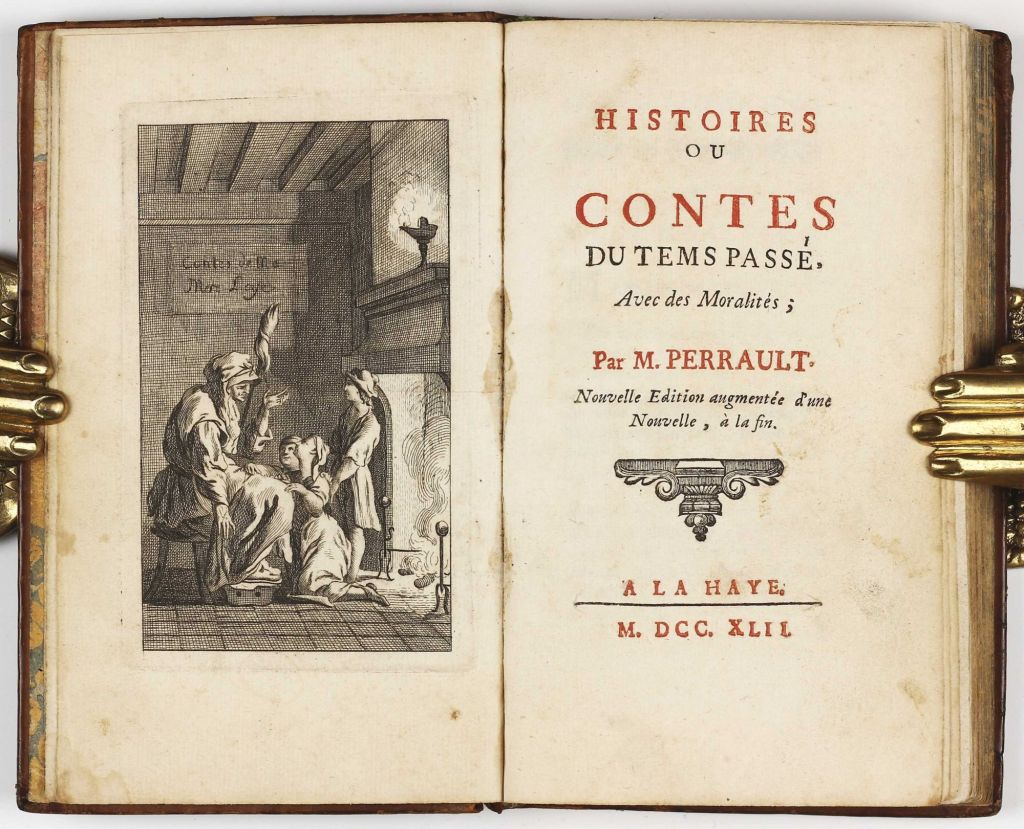

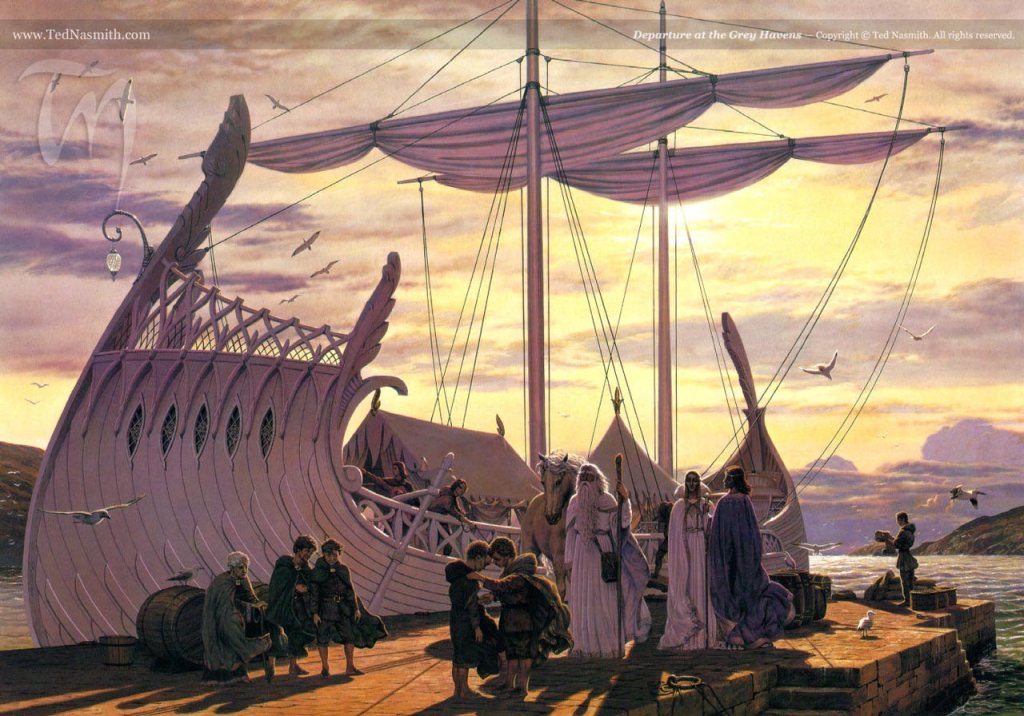

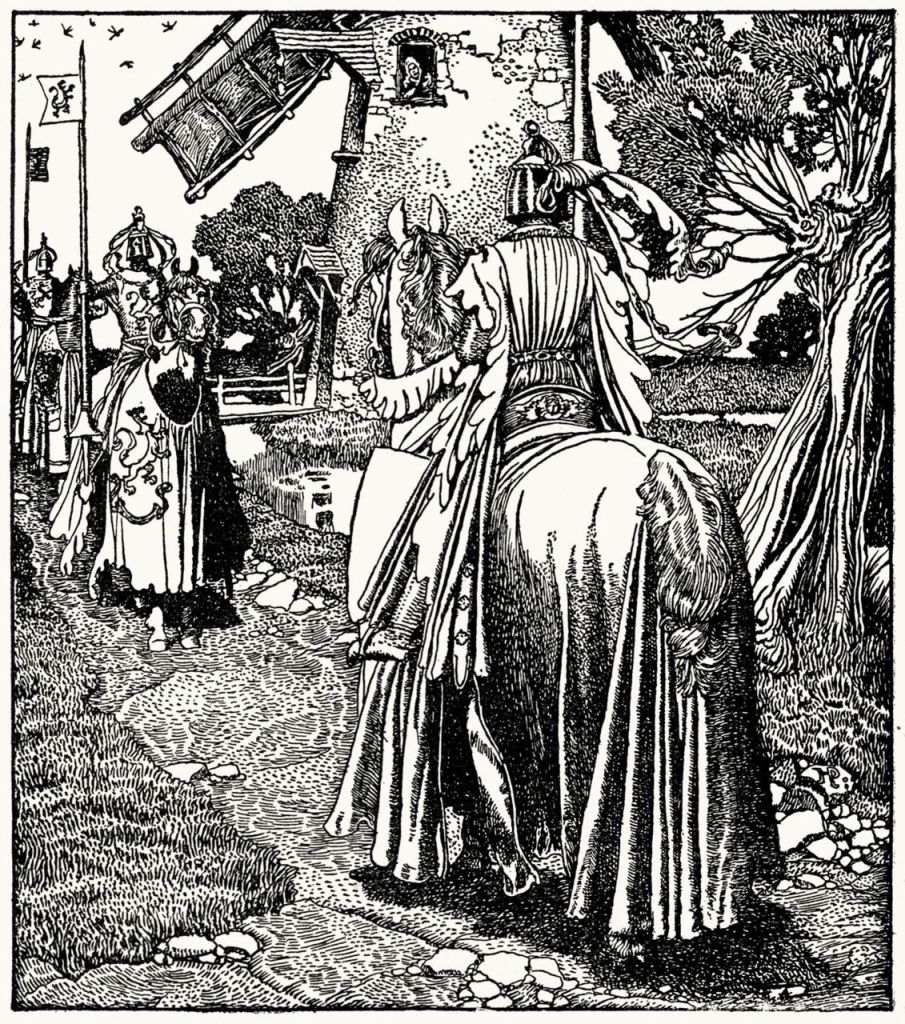

The Third Age in Middle-earth is, at base, a medieval world, the kind of place Tolkien, as a boy, would have seen through the eyes of illustrators like Howard Pyle (1853-1911)

(from his The Story of King Arthur and his Knights, 1903, which you can read here: https://archive.org/details/storykingarthur02pylegoog/page/n15/mode/2up )

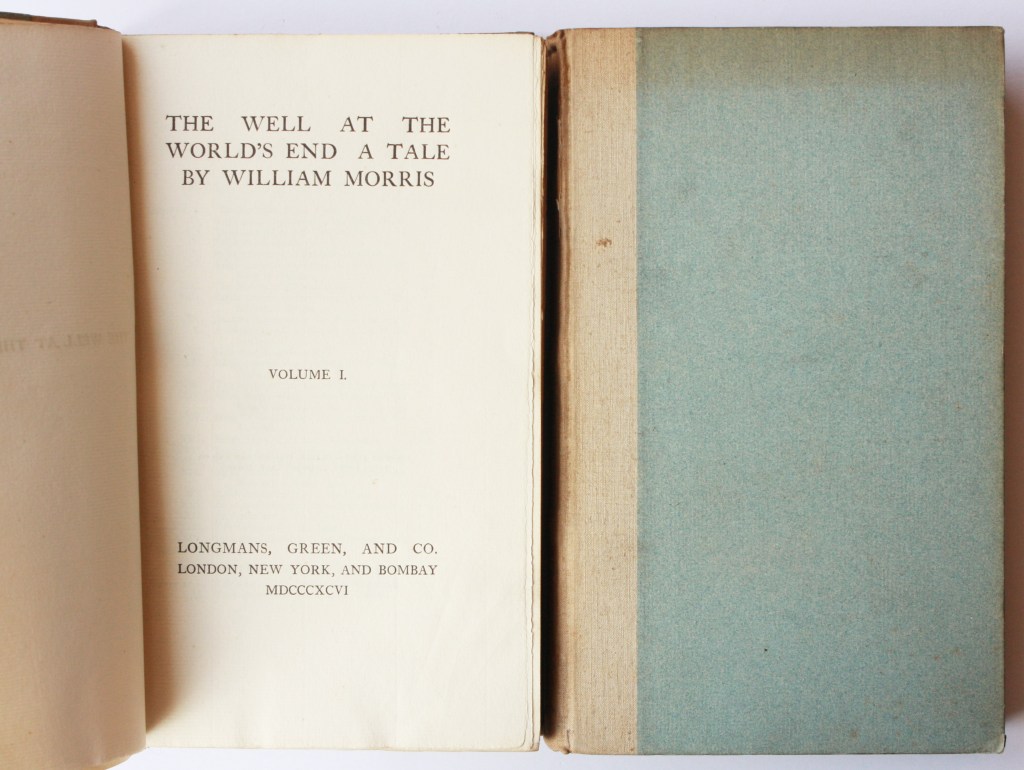

and the writings of authors like his favorite, William Morris (1834-1896).

(You can read this here: https://gutenberg.org/cache/epub/169/pg169-images.html )

Toys like that Marklin train above, therefore, wouldn’t have been available,

but, as Tolkien shows us a clock on the right-hand wall of the entryway at Bag End,

and, as mechanical toys were certainly for sale in the later Victorian world,

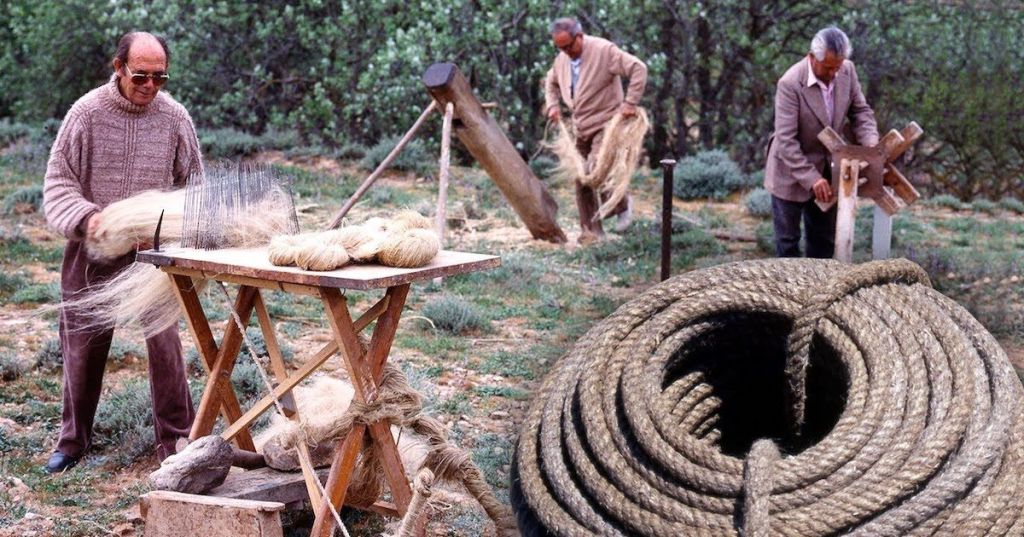

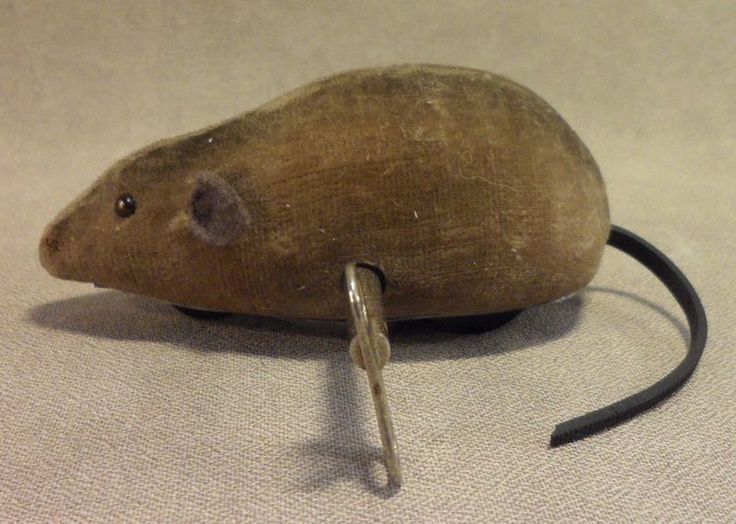

perhaps we can imagine something like this on sale in the Dale toy market?

or this?

always remembering that, although these might seem crude to us, they are antiques and worn from being once much-loved and much-played with, and, in medieval Middle-earth, anything which moved without being pushed or pulled would be magical!

Thanks for reading, as always.

Stay well,

Remember what JRRT said about keeping Christmas magical,

And remember, as well, that there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

There are many sites for early mechanical toys, some informational, some for collectors, and some both at once. Here’s one which is fun to read and has a practical side: https://www.unclealstoys.com/origin-of-wind-up-toys-discovering-the-fascinating-history/