Welcome, dear readers, as always.

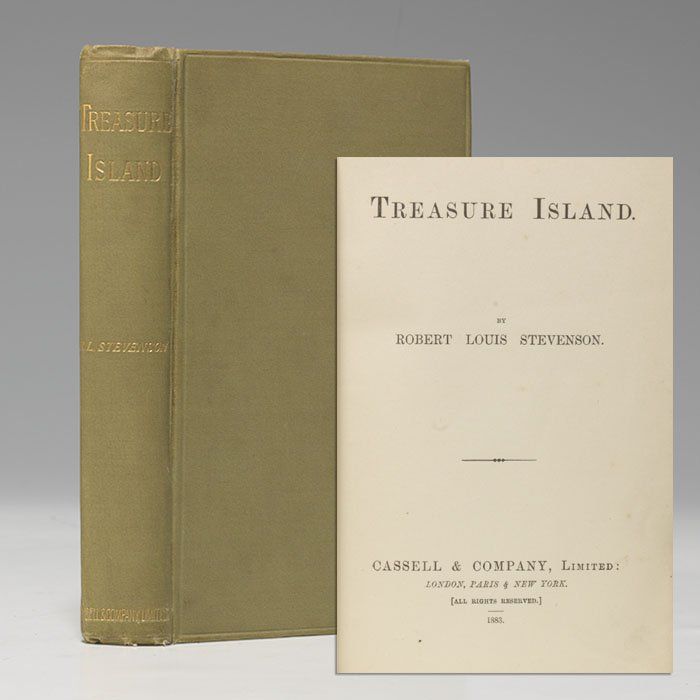

Although the hero of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, 1883,

is the young narrator, Jim Hawkins, the other major character is a rascal, Long John Silver.

If you haven’t read the book, it’s a story about buried treasure (surprised?), a map,

and a voyage to find that treasure—with a crew the half of which are, unknown at first to the protagonists, (temporarily) retired pirates, led by the cook, Silver, of the pirate captain who buried the treasure, Flint.

It’s easy to see why Silver is the other major character: charming and cold-blooded by turns, he dominates those pirates and yet clearly has a soft spot in his heart for Jim Hawkins. At the book’s end, while the other pirates are defeated and killed or marooned on the island, we hear that:

“Silver was gone…But that was not all. The sea-cook had not gone empty-handed. He had cut through a bulkhead unobserved, and had removed one of the sacks of coin, worth, perhaps, three or four hundred guineas, to help him on his further wanderings.

I think we were all pleased to be so cheaply quit of him.”

The other protagonists, like Squire Trelawney and Doctor Livesey,

are sympathetic, but pale in comparison with Silver, one moment genial, the next, treacherous. (Treasure Island, Chapter XXXIV “And Last”)

And so at least I, as a reader, have always been pleased as well. (If you want to read the story in my favorite edition, from 1911, illustrated by N.C. Wyeth, here it is: https://archive.org/details/treasureisland00stev/page/n5/mode/2up )

There is a tradition of having, at worst, a sneaking affection for a villain which dates in English literature at least as far back as the Romantics, when the Satan of Milton’s Paradise Lost, 1667/1674, is seen as other than the destroyer of Paradise. Shelley, in his introduction to his Prometheus Unbound, 1820, almost casually refers to Satan as “the Hero of Paradise Lost” and Blake, in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 1790-1793, says of Milton that

“The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels and God, and at liberty when of Devils and Hell, is because he was a true poet, and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.” (“The Voice of the Devil” 3. “Energy is Eternal Delight”—But I hasten to point out that there has been an enormous amount of scholarly ink spilled over what Blake may actually have meant by this—for my purpose, however, we’ll leave it as a kind of “sympathy for the Devil”.)

Both of these Romantics found Satan more interesting than Adam and angels—in his adversarial relationship to Heaven, he’s simply more developed, and therefore not only more realistic, but, in his way, more dangerous—and tempting.

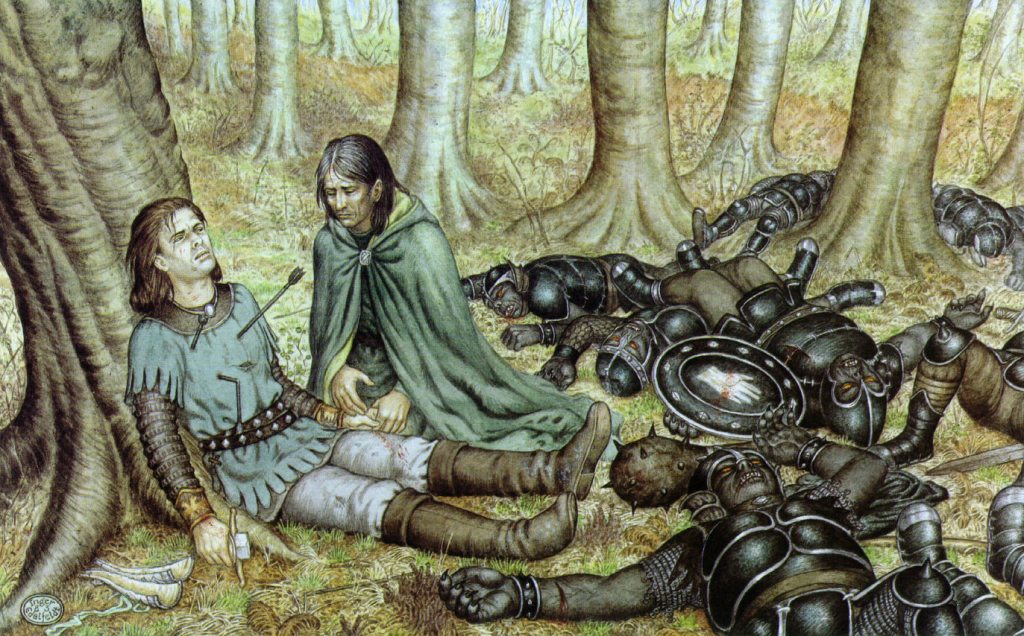

And this is why I have a soft spot for Orcs. It’s not that I admire their behavior, from murdering Boromir

(Inger Edelfeldt)

to murdering each other,

(Alan Lee—this is the pre-murder stage—very soon the archer will shoot an arrow into the other’s eye—see The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 2, “The Land of Shadow”)

but that Tolkien has brought them to life through his use of dialogue: these are real foot soldiers in a real war and vivid because of it, even if they’re villains.

In the draft of a letter from 1956, he had written:

“My ‘Sam Gamgee’ is indeed, as you say, a reflexion of the English Soldier, of the privates and batmen I knew in the 1914 war, and recognized as so far superior to myself.” (draft of a letter to H. Cotton Minchin, not dated, although JRRT noted that some version was sent 16 April, 1956, Letters, 358)

Although I would worry if Tolkien thought that the Orcs were superior to anyone, starting with himself, I would suggest that they are also modeled on the soldiers he knew in the Great War (note, by the way: “batmen” here means “officers’ servants” not Bruce Wayne and descendants).

Consider, in comparison, the dialogue of the two Gondorian soldiers, Mablung and Damrod, we overhear when they are keeping an eye on Frodo and Sam—it seems more like an ancient history lesson than the talk of men in the trenches:

“ ‘Aye, curse the Southrons!’ said Damrod. ‘ ‘Tis said that there were dealings of old between Gondor and the kingdoms of the Harad in the Far South; there was never friendship. In those days our bounds were away south beyond the mouths of Anduin, and Umbar, the nearest of their realms, acknowledged our sway.’ “ (The Two Towers,Book Three, Chapter 4, “Of Herbs and Stewed Rabbit”—I might add that “acknowledged our sway” sounds more like William Morris, 1834-1896, a strong influence on Tolkien, and one who revived archaic language in his writings, than the speech of ordinary infantry of any age.)

Now here are two Orcs, Grishnak and Ugluk, who sound more like Great War sergeants than historians:

“At that moment Pippin saw why some of the troop had been pointing eastward. From that direction there now came hoarse cries, and there was Grishnakh again, and at his back a couple of score of others like him: long-armed crook-legged Orcs. They had a red eye painted on their shields. Ugluk stepped forward to meet them.

‘So you’ve come back?’ he said. ‘Thought better of it, eh?’

‘I’ve returned to see that Orders are carried out and the prisoners safe,’ answered Grishnakh.

‘Indeed!’ said Ugluk. ‘Waste of effort. I’ll see that orders are carried out in my command. And what else did you come back for? Did you leave anything behind?’

‘I left a fool,’ snarled Grishnakh. ‘But there were some stout fellows with him that are too good to lose. I knew that you’d lead them into a mess. I’ve come to help them.’ “ (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 3, “The Uruk-hai”)

And what about this bit of reminiscence and wary conversation between Gorbag and Shagrat:

“…What d’you say?—if we get a chance, you and me’ll slip off and set up somewhere on our own with a few trusty lads, somewhere where there’s good loot nice and handy, and no big bosses.’

‘Ah!’ said Shagrat. ‘Like old times!’

‘Yes,’ said Gorbag. ‘But don’t count on it. I’m not easy in my mind. As I said, the Big Bosses, ay,’ his voice sank almost to a whisper, ‘ay, even the Biggest, can make mistakes. Something nearly slipped, you say. I say, something has slipped. And we’ve got to look out. Always the poor Uruks to put slips right, and small thanks. But don’t forget: the enemies don’t love us any more than they love Him, and if they get topsides on Him, we’re done too…’ “ (The Two Towers, Book Four, Chapter 10, “The Choices of Master Samwise”)

You won’t love them, considering their behavior towards Merry and Pippin, Frodo and Sam, you’ll probably be glad that at least 3 out of 4 are killed (Shagrat, though wounded by Snaga, escapes to report to the Barad-dur—see The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 1, “The Tower of Cirith Ungol”), but, perhaps, like me, you might remember Tolkien’s description of the Orcs to Peter Hastings:

“…fundamentally a race of ‘rational incarnate’ creatures, though horribly corrupted, if no more so than many Men to be met today.” (draft of letter to Peter Hastings, September, 1954, Letters, 285)

and find that, like “many Men to be met today”—and even for fictional men, like Long John Silver—you can have, as JRRT seems to, a brief moment of sympathy for them in their corruption as well as admitting that they can often be a lot more engaging than their virtuous Gondorian and Rohirric opponents.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

Beware the temptation of the Dark Side, even if it makes you want to turn the page and read on,

And remember that there’s always

MTCIDC

O