Welcome, as always, dear readers.

If you read this blog regularly, you know that one thing which always interests me is Tolkien’s sources, both direct and indirect. In my last, for example, you would have read about one which he directly acknowledged, S.R. Crockett’s 1899 historical novel, The Black Douglas.

(See “Wolfing”, 11 September, 2024 for more)

In this posting, however, I want to begin with a source which prompted my writing this.

It is a pair of stanzas from Theophile Gautier’s (1811-1872)

poem “L’Art”, which I read just the other day (my translation)–

“Toute passe—L’art robuste

Seul a l’eternite;

Le buste

Survit a la cite.

Et la medaille austere

Que trouve un laboureur

Sous terre

Revele un empereur.”

“Everything passes–only sturdy art

To eternity;

The bust survives the city

And the austere medallion

Which the workman finds

Under the ground

Reveals an emperor.”

Gautier belonged to the beginnings of a 19th-century movement which was called “Art for Art’s Sake” and this poem is a declaration, directed towards artists themselves, of his belief that art survives—and should survive—the ages.

What really caught my attention was the second of these two stanzas, first because the medallion reminded me of this medallion, which I use to teach the Germanification of the later western Roman Empire–

It was minted for the first Ostrogothic king, Theoderic (454-526), who controlled Italy and some areas to the east from 493-526AD, ruling as an ostensible agent of the eastern Roman Empire, but actually a kind of smaller version of the former western Roman emperors. I’ve always found this image useful because it suggests several things at once:

1. although it’s in Latin (“Theodericus Rex Pius Princi[p]s—for “Princeps”—originally “Headman”—primum caput—in Roman Republican terms, the speaker of the Senate—later an imperial honorific—now the basis of our word “prince”), “Theoderic, king, religious, prince”, underneath that name is the Gothic language which, along with Latin and Greek, Theoderic (or the older spelling, Theodoric) spoke, his Gothic name being something like “Thiudareiks”. The Greco-Roman name would mean “Gift of God (theo- god, originally Zeus, + dor- gift)”, whereas the Gothic name is a compound of thiuda, “people” and reiks, “ruler”, so “ruler of the people”. And the name, being in two languages at once, would seem to suggest, perhaps inadvertently, that Theoderic is the ruler of both the older Roman population and the newer Gothic.

2. this message is underlined by the portrait of the king himself–although he has the general look of a later Roman ruler—his lamellar armor (armor made of overlapping metal plates) and the little Nike (not sneaker, but the angelic figure in his left hand, symbolizing victory)—his haircut and the mustache are definitely not, being Germanic.

(For more on this medallion, see: https://pancoins.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Theorodoric-entire-article.pdf and https://cccrh.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/the-coins-of-theoderic-the-ostrogoth.pdf )

The second reason that stanza caught my attention was Gautier’s suggestion that the medallion, along with the bust, are archaeological finds which have survived as emblems of a previous age, itself long lost.

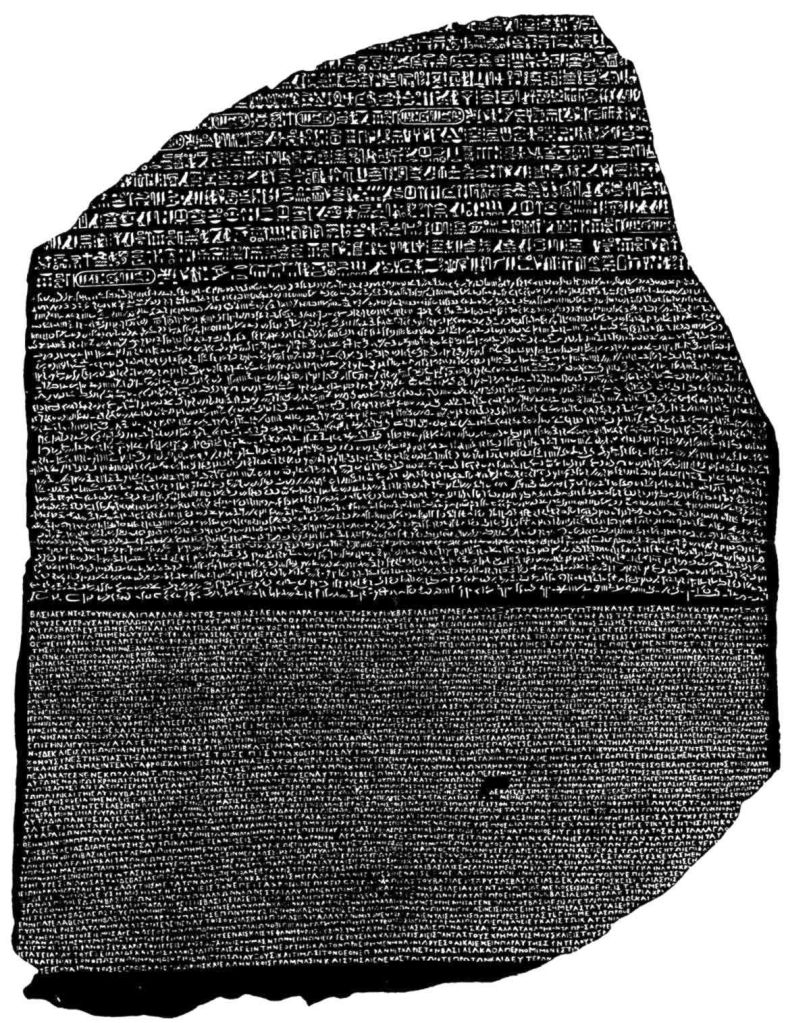

Sometimes, as in the case of Gautier’s workman, finds are simply stumbled upon. The famous Rosetta Stone, for example,

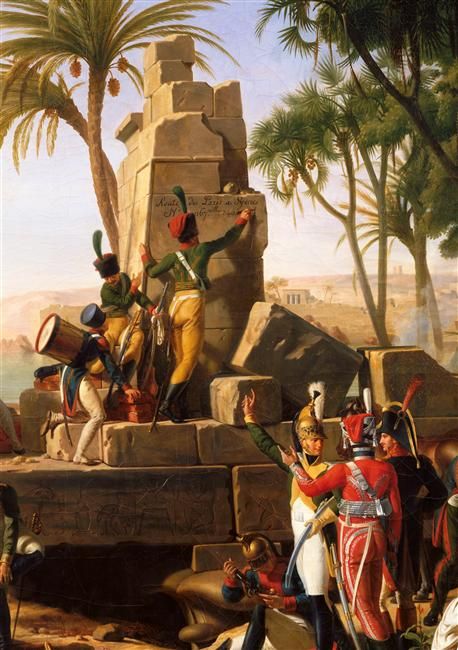

was found built into a wall by French engineers from Napoleon’s 1798 invasion of Egypt,

who were, in fact, not looking for antiquities (although Napoleon’s expeditionary force actually had a scientific element attached—here’s an image of one of the volumes which, eventually, they published),

but were improving some fortifications at the time.

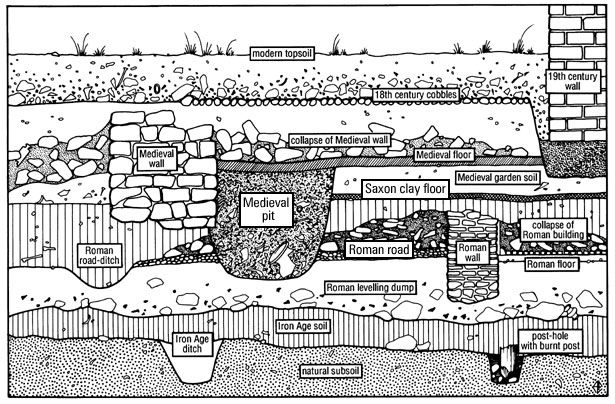

As time went on, however, scientific archaeology developed and began very carefully recording discoveries brought from the ground layer by layer, which is called stratigraphy, and is used by geologists and paleontologists, as well.

The thinking behind this is simply logical: that which you find below something else is older (unless the ground is disturbed, which can and does happen), that which you find above is newer.

Something I’ve always loved about Tolkien’s work (and Tolkien himself) is the careful, patient way he’s built up Middle-earth, which is, in fact, stratigraphically designed. For an easy example, look at Appendix A of The Lord of the Rings:

“Annals of the Kings and Rulers”,

which is then divided into:

“I The Numenorean Kings”

which is then subdivided in turn into:

“(i) Numenor

(ii) The Realms in Exile

(iii) Eriador, Arnor, and the Heirs of Isildur

(iv) Gondor and the Heirs of Anarion

The Stewards”

to which is added

(v) Here Follows a Part of the Tale of Aragorn and Arwen”

before we move on to

“II. The House of Eorl”

Layer by layer, JRRT piles on time and its events—and this isn’t just in annalistic form—that is, a date is provided, then an event is briefly recorded (although we see this form at the beginning of Appendix B in“The Tale of Years”)—instead, we find whole short stories, like that of King Arvedui, which occupies about 2 full pages in the 50th anniversary edition which I use in these postings (1041-1043).

The consequence of this is always a sense that Middle-earth is extremely old, inhabited, colonized, with stratum after stratum of human/elvish/dwarfish activity laid on top of each other—and sometimes standing long after those originally involved are long gone. Consider, for example, the “Pukel-men”:

“At each turn of the road there were great standing stones that had been carved in the likeness of men, huge and clumsy-limbed, squatting cross-legged with their stumpy arms folded on fat bellies. Some in the wearing of the years had lost all features save the dark holes of their eyes that still stared sadly at the passers-by…

Such was the dark Dunharrow, the work of long-forgotten men. Their name was lost and no song or legend remembered it. For what purpose they had made this place, as a town or secret temple or a tomb of kings, none in Rohan could say. Here they laboured in the Dark Years, before ever ship came to the western shores, or Gondor of the Dunedain was built; and now they had vanished, and only the old Pukel-men were left, still sitting at the turnings of the road.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 3, “The Muster of Rohan”)

On its own, this careful, detailed building of the past gives tremendous power to present events: for ages, other people have struggled, built, fought, and perished in Middle-earth and left behind a long record of their deeds—although sometimes only nearly-forgotten monuments are all that survives.

But I think that we might also see a larger picture here, as well.

Middle-earth was not chosen just because Tolkien, as a medievalist, had it in his vocabulary. As he tells us:

“I am historically minded. Middle-earth is not an imaginary world. The name is the modern form (appearing in the 13th century and still in use) of midden-erd >middel-erd, an ancient word for the ‘oikoumene’, the abiding place of Men, the objectively real world, in use specifically opposed to imaginary worlds (as Fairyland) or unseen worlds (as Heaven and Hell). The theatre of my tale is this earth, the one in which we now live, but the historical period is imaginary. The essentials of that abiding place are all there (at any rate for inhabitants of N.W. Europe), so naturally it feels familiar, even if a little glorified by the enchantment of distance in time.” (“Notes on W.H. Auden’s review of The Return of the King, 1956?, Letters,345)

To which we might add:

“May I say that all this is ‘mythical’…As far as I know it is merely an imaginative invention, to express, in the only way I can, some of my (dim) apprehensions of the world. All I can say is that, if it were ‘history’ it would be difficult to fit the lands and events (or ‘cultures’) into such evidence as we possess, archaeological or geological, concerning the nearer or remoter part of what is now called Europe…I could have fitted things in with greater verisimilitude, if the story had not become too far developed, before the question ever occurred to me. I doubt if there would have been much gain; and I hope the, evidently long but undefined, gap in time between the Fall of Barad-dur and our Days is sufficient for ‘literary credibility’, even for readers acquainted with what is known or surmised of ‘pre-history’. “

And Tolkien has footnoted this with:

“I imagine the gap to be about 6000 years: that is we are now at the end of the Fifth Age, if the Ages were about the same length as S.A. and T.A. But they have, I think, quickened; and I imagine we are actually at the end of the Sixth Age, or in the Seventh.” (Letter to Rhona Beare, 14 October, 1958, Letters, 404)

In other words, what Tolkien has done for his version of our world is to create a simulacrum of what humans in time have done for our version of our world and, as we read The Lord of the Rings, including its appendices, we are acting as something like literary archaeologists, beginning at the surface of the Third Age in its last years and reading slowly down through its strata, just as archaeologists in our world work their way down through the historical layers, recording the strata as they dig. Although I’m admirer of good fan fiction, I don’t think that I would ever write it, but I can imagine a story which begins with an archaeologist in our world (6000 years after the Third Age) digging more deeply than ever and coming upon

“…a tall pillar loomed up before them. It was black; and set upon it was a great stone, carved and painted in the likeness of a long White Hand…” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 8, “The Road to Isengard”)

Where might the story go from there?

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

When excavating always keep a careful record,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O