Tags

Barrow-wight, Finnegans Wake, Giambattista Vico, goblin king, James Joyce, La Scienza Nuova, lotr, Mirkwood spiders, Nazgul, Ouroboros, Palantir, runes, Shelob, swords, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Return of the King, Tolkien, Tom Bombadil, Yogi Berra

“It’s déjà vue all over again.”

(attributed to Yogi Berra, US baseball player, but see: https://quoteinvestigator.com/2013/10/08/deja-vu-again/ )

Dear readers, as always, welcome.

In later life, James Joyce, 1882-1941,

was interested in the work of the 17-18th-century philosopher (among other things) Giambattista Vico, 1668-1744,

and his idea that history followed a definite repeated pattern in three ages, Divine, Heroic, and Human, posited in his 1725-1744 work, La Scienza Nuova (“the new understanding, knowledge, learning”).

(For more on Vico, see: https://www.philosopheasy.com/p/the-eternal-return-giambattista-vicos This is, potentially, a very large subject, and even more so when Joyce is combined with Vico. For an introductory view, see: https://archive.org/details/vicojoyce00vere_0/page/n5/mode/2up )

Joyce incorporated his understanding of Vico in his last work, Finnegans Wake, 1939, in which

the idea of repeated patterns cycling throughout appears in the very opening—and closing– lines of the book:

“A way a lone a last a loved a long the / riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.”

which, in fact, are reversed, the opening of the book being:

“…riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs…”

and the last words of the book are:

“A way a lone a last a loved a long the…”

so that, by joining them, we have the effect of the serpent Ouroboros, tail/tale joined to mouth—and the book can begin again.

(For more on Finnegans Wake, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Finnegans_Wake For more on the serpent, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ouroboros )

I’ve always thought that leaving Tom Bombadil and the Barrow-wight

(Matthew Stewart—see more of his work here: https://www.matthew-stewart.com/ See, in particular, his Middle-earth work, but then go through his other galleries to view his impressive ability to capture other imaginary worlds.)

out of the first Lord of the Rings film was a mistake, even though Tolkien himself once wrote:

“Tom Bombadil is not an important person—to the narrative.” (letter to Naomi Mitchison, 25 April, 1954, Letters, 268—but read on, as JRRT has much more to say and, to my mind, justifies his position in the narrative, in fact, in a spiritual way.)

Tom is interesting in himself, being a kind of parallel for Treebeard, among other things (and the writers of the Rings of Power series thought highly enough of him to include him in their telling), but, for me, in the narrative, it’s what he gives them, particularly Merry, which is important—

“For each of the hobbits he chose a dagger, long, leaf-shaped, and keen, of marvelous workmanship…”

(probably something like this, but more elaborately-worked)

‘Old knives are long enough as swords for hobbit-people,’ he said…Then he told them that the blades were forged many long years ago by Men of Westernesse: they were foes of the Dark Lord, but they were overcome by the evil king of Carn Dum in the Land of Angmar.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 8, “Fog on the Barrow-downs”)

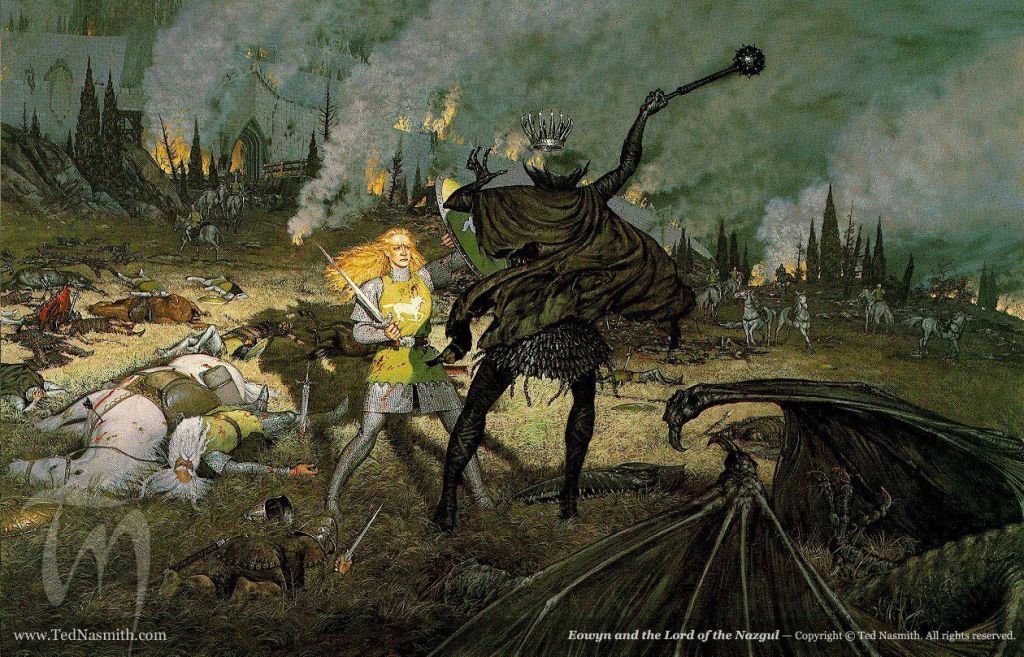

This is, of course, the weapon which Merry uses to stab the chief of the Nazgul while he’s attacking Eowyn, the Nazgul being the very witch-king who had overcome the Men of Westernesse so long before.

(Ted Nasmith)

To keep Tom and the Barrow-wight in the film is then to underline the cyclic nature of much of the story.

This unnamed but crucial sword is only one of the swords scattered throughout the later story of Middle-earth, however, and there is a cyclic potential for others, as well.

Think of the swords which Gandalf and Co. find in the trolls’ hideout in The Hobbit—

“…and among them were several swords of various makes, shapes, and sizes. Two caught their eyes particularly, because of their beautiful scabbards and jeweled hilts…

‘These look like good blades,’ said the wizard, half drawing them and looking at them curiously. ‘They were not made by any troll, nor by any smith among men in these parts and days; but when we can read the runes on them, we shall know more about them.’ “ (The Hobbit, Chapter Two, “Roast Mutton”)

In the next chapter, Elrond then identifies them:

“Elrond knew all about runes of every kind. That day he looked at the swords they had brought from the trolls’ lair, and he said: ‘These are not troll-make. They are old swords, very old swords of the High Elves of the West, my kin. They were made in Gondolin for the Goblin-wars. They must have come from a dragon’s hoard or goblin plunder, for dragons and goblins destroyed that city many ages ago. This, Thorin, the runes name Orcrist, the Goblin-cleaver in the ancient tongue of Gondolin; it was a famous blade. This, Gandalf, is Glamdring, a Foe-hammer that the king of Gondolin once wore.’ “ (The Hobbit, Chapter Three. “A Short Rest”)

And you’ll remember that Gandalf runs the king of later goblins through in the next chapter with that very sword:

“Suddenly a sword flashed in its own light. Bilbo saw it go right through the Great Goblin as he stood dumb-founded in the middle of his rage. He fell dead, and the goblin soldiers fled before the sword shrieking into the darkness.” (The Hobbit, Chapter Four, “Over Hill and Under Hill”)

(Alan Lee)

The knife which Bilbo picks up from the trolls’ hoard “only a tiny pocket-knife for a troll, but it was as good as a short sword for the hobbit”, comes in handy later in The Hobbit, when Bilbo uses it to kill some of the spiders of Mirkwood,

(Oleksiy Lipatov—you can see more of his work here: https://www.deviantart.com/lipatov/gallery/85631839/old-comic )

but it will reappear many years later in The Lord of the Rings, when Frodo and Sam use it against another ancient evil, Shelob–

(Ted Nasmith again—and, unusually for his work, just plain weird—but vivid!)

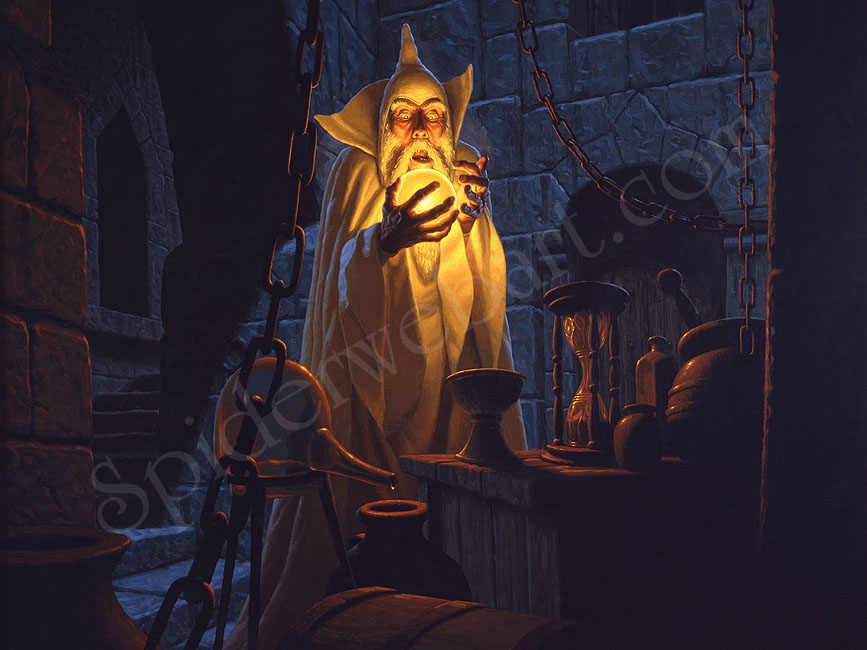

Perhaps the most consequential sword to return, however, is that which maimed Sauron many centuries ago, causing him to lose the Ring, and which, reforged, Aragorn shows him in Saruman’s palantir

(the Hildebrandts)

(itself appearing from a far older world, being as Aragorn says, “For this assuredly is the palantir of Orthanc, from the treasury of Elendil, set here by the Kings of Gondor.” The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 11, “The Palantir”):

“…The eyes in Orthanc did not see through the armour of Theoden; but Sauron has not forgotten Isildur and the sword of Elendil. Now in the very hour of his great designs the heir of Isildur and the Sword are revealed; for I showed the blade re-forged to him. He is not so mighty yet that he is above fear; nay doubt ever gnaws him.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 2, “The Passing of the Grey Company”)

And there are more cyclings.

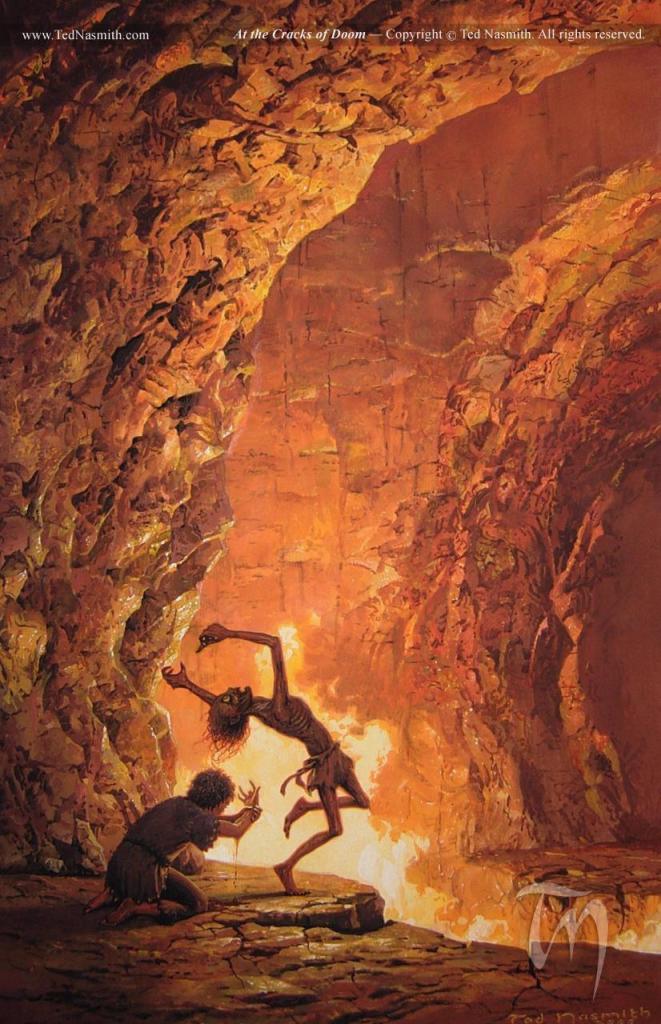

Consider the Ring itself: forged in the fires of Mt Doom, it is eventually returned there and destroyed,

(another Ted Nasmith)

which causes the final end of Sauron, after several ages of struggle,

and which, in turn, brings the—return of the King.

(Denis Gordeev–and note that the artist has painted Aragorn’s crown as depicted by Tolkien in a letter to Rhona Beare, 14 October, 1958, see Letters, 401.)

After thinking about this, I can see that there are even more cyclic events, like the movement of the elves westwards, and Gandalf traveling the same way, originally sent eastwards to oppose Sauron,

(one more Ted Nasmith)

but I think that this is enough for one posting—though considering all of the cycles I’ve already identified, I’ll end with another (supposed) quotation from Yogi Berra:

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

Remember one more piece of Yogi wisdom

And remember, as well, that there’s always

MTCIDC

O