Tags

Agincourt, bicycle, Boer War, cavalry charges, Charge of the Light Brigade, Cu Chulainn, Dwarves, Fredegunda, Gregory of Tours, heavy artillery, Historia Francorum, Hobbits, horses, King Edward's Horse, lotr, machine gun, machine-guns, Nazgul, Normans, Pegasus, Rohirrim, Russian Civil War, signals officer, Sleipnir, The Hobbit, Tolkien, Valkyries

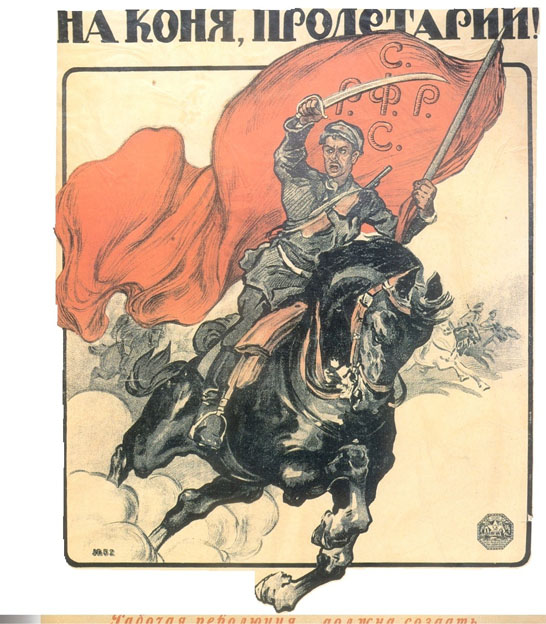

In a colleague’s office, I once saw this on his wall—

“Proletariat, to horse!”

It’s a recruiting poster from the Russian civil war (1918-1922), showing the Reds trying to raise cavalry for their armies, but, at the time this call came, the military world was changing and, although horsemen would still appear, very sporadically, on battlefields, for some years to come, the day of events like this—

was rapidly coming to a close.

It didn’t happen all at once, however. As you can imagine, traditional cavalrymen—those who believed that swinging a sword in a valiant charge was the point of cavalry—

fought back. The evidence was against them, however, in two ways.

First, in the case of the British, there had been the Boers,

with whom the British had fought a war, from 1899-1902. The Boers (Dutch for “farmers”) had been militia—men obliged by law to defend the state upon demand. Across the wide open spaces of so much of South Africa, they had fought as mounted infantry, using horses as a means of moving from place to place, then dismounting for combat and, if things didn’t go their way, mounting up and escaping.

To counter this, especially in the later phases of the war, the British were forced to develop their own mounted infantry,

which suggested to some military theorists at the time that the wave of the future was not in sword-swingers, but in riflemen, who could rapidly move to where they were needed, but employ horses for transport, not for gallant charges. (This also led to the rise of units mounted entirely on bicycles,

but we can imagine the off-road difficulties for early machines and, although there were bicycle units as late as WW2, they never had the popularity—or the dash—of horsemen.)

The second piece of evidence lies in technological change.

With the coming of the 20th century, machine guns, sometimes firing as many as 600 rounds (shots) per minute,

appeared in increasing numbers and artillery was developed to become more accurate at greater distances.

In self-defense, soldiers would be forced to take cover wherever they could,

at first in holes simply scraped out of the ground, but, in time, in very sophisticated lines, shored up with wood and metal and sandbags.

On the Western Front, where everyone was dug into the ground, and being in the open could mean instant destruction, there simply wasn’t a place for old-fashioned cavalry, for all that there were still lots of old-fashioned cavalrymen in the army—like the first commander of the British in France in 1914, Sir John French.

Imagine, then, that this was all happening when Tolkien was very young—when the Boer War ended, in 1902, for instance, he would have been only 10.

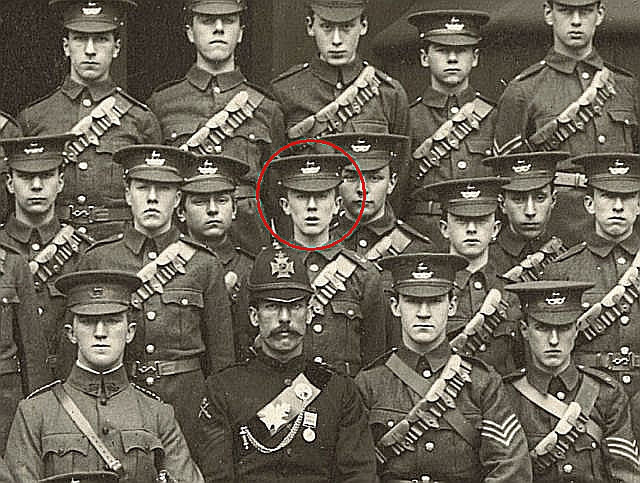

(JRRT and his brother, Hillary, in 1905)

His own military career had begun at King Edward’s School in Birmingham, when he entered the new Cadet Corps in 1907.

(For more, see this essay by John Garth: https://johngarth.wordpress.com/2014/03/05/tolkien-at-fifteen-a-warrior-to-be/ )

Then, in the summer of 1912, he was briefly a member of a territorial (a sort of national guard unit) cavalry regiment, King Edward’s Horse. (The reference here is to Carpenter’s J.R.R.Tolkien, 66. John Garth later added detail to this, but subsequently qualified it, saying that his evidence was faulty. See: https://oxfordinklings.blogspot.com/2009/06/tolkien-and-horses.html )

(Officers of the regiment about 1916)

It was clearly an indication of the drop in the use of cavalry, however, when JRRT began his second enlistment not in a cavalry, but an infantry regiment, the Lancashire Fusiliers, in which he was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in 1915.

In his brief battlefield career, he was the signals officer for his battalion, the 11th. In the advance into the Somme in July, 1916, Tolkien, although armed with a revolver,

would have been too busy to do any fighting as his work involved

“More code, flag and disc signaling, the transmission of messages by heliograph and lamp, the use of signal rockets and field-telephones, even how to handle carrier pigeons…” (Carpenter, 86)

To ask for reinforcements, as well as to avoid artillery fire which could be called in to fend off German counterattacks, but which might hit friendly troops instead, it was extremely necessary for attacking units to let their positions and situations be known as often as possible, so JRRT would have been more than a little occupied during the months (1 July-18 November, 1916) of the very costly (nearly 58,000 British casualties the first day alone) offensive. Fortunately for him—and for us—he fell ill with so-called “trench fever” and left France for good early in November, going home to England and, ultimately, to Middle-earth.

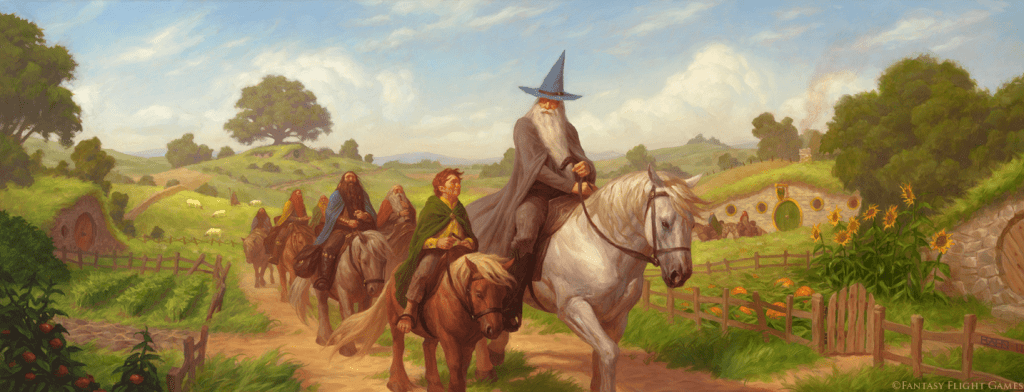

Although his military service in the field was relatively brief, and his career with cavalry even briefer (he resigned from King Edward’s Horse in January, 1913), we see horses everywhere in Middle-earth, from the ponies of the dwarves in The Hobbit

(from Painting Valley—no artist listed)

to the horses of the Nazgul in The Lord of the Rings.

(with the Gaffer, one of my favorite illustrations by Denis Gordeev)

But, although cavalry might have been only a brief flirtation for Tolkien, horses had been part of his life since its beginnings. Part of this would have been mundane—it was only after the Great War that the internal combustion engine really began to dominate the streets. When JRRT was young, Birmingham and London, as well as Berlin, Paris, and New York, would have looked like this—

His early reading would have given him Bellerophon on Pegasus,

to which would have been added the Valkyries,

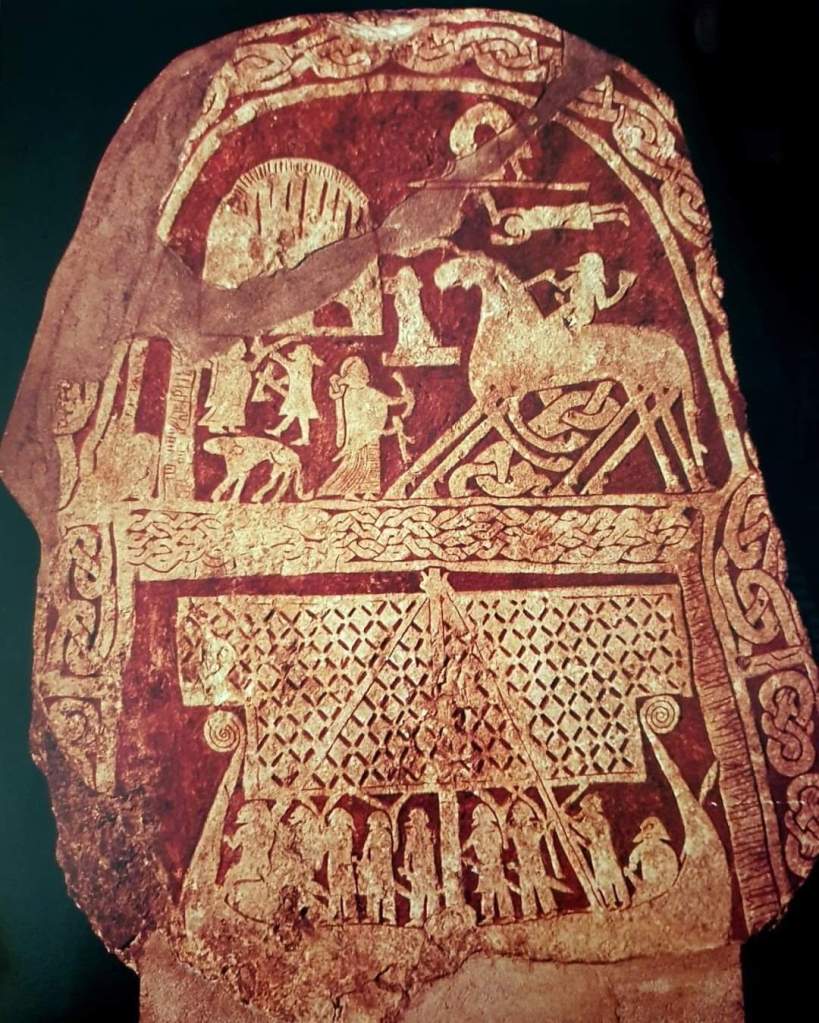

and, in time, Sleipnir, Odin’s 8-legged steed,

(This is the Tjaengvide image stone, one of a group of runic stones, called the “Sigurd stones”, found in Sweden and dated to between 700 and 1100AD. You can read more about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tj%C3%A4ngvide_image_stone You can read about the other stones here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sigurd_stones Tolkien would first have heard about Sigurd from Andrew Lang’s The Red Fairy Book, 1890, which you can find here: https://archive.org/details/redfairybook00langiala/redfairybook00langiala/mode/2up Sigurd himself possessed the offspring of Sleipnir, Grani, which you can read about here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grani )

and further medieval reading would have filled his mind with mythic and magic horses, like Cu Chulainn, the Irish hero’s, chariot pair, water horses named Liath Macha and Dub Sainglend (although he wasn’t very enthusiastic about Old Irish literature which, I suspect, he found much wilder and stranger and more disturbing than, say, the Welsh Mabinogion, which you can read about here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mabinogion )

(a rather over-the-top image by the usually dependable Angus McBride—someone should have mentioned to him that, although “Dub” means “black”, Liath means “grey”. Cu Chulainn is one of my favorite ancient berserkers—to mix cultures—and, if you don’t know him, you can begin to read about him here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C%C3%BA_Chulainn )

But there are magical horses in many places—see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_horses_in_mythology_and_folklore for many more, with at least many of the medieval, he would have been familiar.

And while we’re speaking of Middle-earth and horses, we need to mention the Normans, who, combined with the Anglo-Saxons for language, were the basis of the Rohirrim–

“The Rohirrim were not ‘medieval’ in our sense. The styles of the Bayeux Tapestry…fit them well enough…” (letter to Rhona Beare, 14 October, 1958, Letters, 401)

The Rohirrim, in turn, lead us back to the opening of this posting. Although, in Tolkien’s day, cavalry and glorious charges,

like that of the British Light Brigade at Balaclava in 1854, commemorated in Tennyson’s poem, were almost at the end of their military usefulness, for a Romantic, like Tolkien, the idea of such a charge was still a powerful image and one he couldn’t resist, depicting the heroic Rohirrim assembling

(from the Jackson film)

and roaring down on the unsuspecting orcs.

(Abe Papakhian)

JRRT was writing medieval fantasy, however, but, as I’m always interested in “what if’s”, here I’m remembering what actually happened to that Light Brigade charge, an attack made in the teeth of Russia artillery.

The consequence was that, out of 609 men who rode towards the Russians, only 198 returned, and Lady Butler’s picture, “Balaclava the Return 25 October 1854” (1911) sums up the actual aftermath of that charge.

There’s evidence in the destruction of the Causeway Forts that Sauron’s army had some sort of blasting powder—suppose, instead of using it just as a siege tool, it had been employed with some sort of projectile propelled by it out of a tube—what might that have done to the Rohirrim’s valiant attack?

Or even using the technique of the English army against the French at Agincourt, in our medieval world of 1415AD: pointed stakes to threaten horses, behind which stood massed bowmen: what would have been the outcome of that?

(Angus Mcbride)

475 horses were lost in the Charge of the Light Brigade. Military progress so often just means more killing, but the replacement of horses with machines seems to me, who loves horses, a turn for the better. At the same time, with Tolkien, I can feel the attraction for wild charges with swords at top speed (although cavalry did better when, at most, it went in at the canter—galloping causes loss of formation which can blunt the effect of such an attack), but, as in the charge of the Rohirrim, I’m glad if they only appear in fiction—and far from modern weaponry.

Thanks, as ever, for reading,

Stay well,

Remember that there’s a special spot, just behind the poll (top of the head), which, if scratched in the right place, makes many horses happy,

And remember, as well, that there’s always

MTCIDC

O

PS

One of those little “what if” quirks of history–Tolkien’s immediate family had been in the Orange Free State at the time of his birth, in 1892. Tolkien’s father, Arthur, was manager of the Bloemfontein branch there of the Bank of Africa. The Orange Free State was one of the Boer republics attacked by Britain in the Boer War of 1899-1902. If Tolkien’s mother hadn’t brought JRRT and his brother, Hilary, back to England, in 1895, and Arthur hadn’t died of the effects of rheumatic fever in 1896,

Tolkien might have been in the Orange Free State when Bloemfontein was occupied by the British on 13 March, 1900. (You can see early film of the Scots Guards marching in here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DHy2cEFwlIo )

PPS

In last week’s posting, I mentioned the story of the wonderfully bloodthirsty Frankish queen Fredegunda, as she appears in Gregory of Tours Historia Francorum. I wrote there that you might read about her assassination of Bishop Praetextatus and her cold-blooded visit to him on his deathbed afterwards—but it required reading Gregory’s 6th-century Latin, as I didn’t provide a translation. It seemed lazy of me not to include one of that scene, however, so here it is with the original Latin. As always, I could smooth this out, but I prefer to stick as close as I can to the text, to give you a better feel for what’s actually been written.

Advenientem autem dominicae resurrectionis diae, cum sacerdos ad implenda aeclesiastica officia ad aeclesiam maturius properasset, antefanas iuxta consuetudinem incipere per ordinem coepit. Cumque inter psallendum formolae decumberet, crudelis adfuit homicida, qui episcopum super formolam quiescentem, extracto baltei cultro, sub ascella percutit. Ille vero vocem emittens, ut clerici qui aderant adiuvarent, nullius ope de tantis adstantibus est adiutus. At ille plenas sanguine manus super altarium extendens, orationem fundens et Deo gratias agens, in cubiculo suo inter manus fidelium deportatus et in suo lectulo collocatus est. Statimque Fredegundis cum Beppoleno duce et Ansovaldo adfuit, dicens: ‘Non oportuerat haec nobis ac reliquae plebi tuae, o sancte sacerdos, ut ista tuo cultui evenirent. Sed utinam indicaretur, qui talia ausus est perpetrare, ut digna pro hoc scelere supplicia susteneret’. Sciens autem ea sacerdos haec dolose proferre, ait: ‘Et quis haec fecit nisi his, qui reges interemit, qui saepius sanguinem innocentem effudit, qui diversa in hoc regno mala commisit?’ Respondit mulier: ‘Sunt aput nos peritissimi medici, qui hunc vulnere medere possint. Permitte, ut accedant ad te’. Et ille: ‘Iam’, inquid, ‘me Deus praecepit de hoc mundo vocare. Nam tu, qui his sceleribus princeps inventa es, eris maledicta in saeculo, et erit Deus ultur sanguinis mei de capite tuo’. Cumque illa discederit, pontifex, ordinata domo sua, spiritum exalavit.

“However, with the coming of the day of [Our] Lord’s resurrection, when the priest [Praetextatus] had hurried early to the church to fulfill [his] ecclesiastical duties, he started to begin [the] antiphons according to custom [in their proper] order. And when, between the psalms, he was lying on a bench, a cruel murderer appeared, who, when a knife had been pulled from [his] belt, struck the bishop, resting on the bench, under the armpit. He [the bishop], however, [although] shouting so that the clergy who were present might help him, was aided with help of none from so many being present. Yet he, stretching his hands, full of blood, above the altar, pouring [out] a prayer and thanking God, was carried off into his bedchamber by the hands of [his] faithful [followers] and placed on his bed. And straightaway Fredegunda, with the Duke Beppolenus and Ansovaldus, appeared, saying, ‘Oh holy priest, this was not right for us and for the rest of your people that such things should happen in your worshipping. But would that it would be revealed who had dared to carry out such things that he should suffer punishment worthy of this crime.’ The priest, knowing, however, that she was speaking of these things deceptively, said, ‘And who has done these things if not [the one] who has killed kings, who very often has poured out innocent blood, who has committed many evil deeds in this kingdom’ The woman replied: ‘There are in our household highly experienced doctors who would be able to heal this wound. Allow [it] that they may come to you.’ And he [said]: ‘God has decreed to call me from this world. On the other hand, you who have been exposed as chief in these crimes, you will be cursed in the future and God will be the avenger of my blood on your head.’ And when she had left, the bishop, affairs arranged in his house, breathed out his spirit.”

And how could I not include Alma-Tadema’s illustration?