Tags

Ballads, deck-us-all-with-boston-charlie, George Washington, god-save-the-king, mondegreen, pogo

As always, dear readers, welcome.

If you read this blog regularly, you probably imagine that, as a small child, I lived in a constant state of puzzlement—and I did. In part, this came from the fact that, before I could read and write, and sometimes after that, I lived in an oral world, where so much of my life was spent hearing things, rather than seeing them in print—and that could lead to interesting results.

For instance, there’s a patriotic song I was taught, probably in kindergarten, which begins:

“My country, ‘tis of thee,

Sweet land of liberty,

Of thee I sing.”

From the oddly convoluted grammar, you might suspect that it was written to an already-existing tune—and you’d be right: it’s set to “God Save the King”. (You can read about its history here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/My_Country,_%27Tis_of_Thee If you think that the use of a tune about a king as the basis for a song for a republic is surprising, just consider: these words date from 1831, but there’s a 1786 song to the same tune entitled “God Save Great Washington”—only 3 years after the founding of a country which had fought for 8 years to escape the very king the original song had been written for.

Here’s a verse from that:

“God save great Washington,

His worth from eve’ry tongue,

Demands applause;

Ye tuneful pow’rs combine,

And each true Whig now join

Whose heart did ne’r resign

The glorious cause.”

About the same level as “My Country, ‘tis of thee”, I would say. This is quoted from a usually very useful source: https://mudcat.org/thread.cfm?threadid=39759 but the work cited there says that the lyric is from The Philadelphia Continental Journal for 7 April, 1786, and, as far as I can determine, there was no such journal in Philadelphia at that time. Perhaps this is a mistake for the Boston-based Continental Journal and Weekly Advertiser, which ran from 1776 to 1787? For a list of 18th-century Philadelphia newspapers, see: https://brainly.infogalactic.com/info/List_of_newspapers_in_Pennsylvania_in_the_18th_century#Philadelphia )

And this is where orality comes in. Hearing a teacher sing this while we stumbled along behind her, I thought that what she sang was “My country, dizzily…” which, even (or perhaps especially) to a small child, was somewhat enigmatic. You can imagine, then, what would be the case had I then tried to teach it to another child, or even an adult.

If you’ve ever played the game called “Whisper Down the Lane” or “Telephone”, you’ve seen what happens when someone initially says something which is then passed down a chain of listeners—you can read more about it at WikiHow here: https://www.wikihow.com/Play-the-Telephone-Game from which this illustration comes.

As the original message passes from mouth to ear to mouth, words change and it’s sometimes quite surprising when, if you had spoken that initial message, you heard the last person in the chain repeat what she or he heard.

It’s also a very good illustration of the effect of oral tradition on songs.

For example, in Child Ballad #200, (formally, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, edited by Francis James Child), with a variety of titles including “The Wraggle Taggle Gypsies, O”. The basic story is that a fine lady is enticed to go off with some Gypsies (a term no longer used, “Romani People” being currently employed, but, in discussing the ballad, I’m going to stick to the older term as that’s what’s in the text) and, in many variants, the idea is that the Gypsies have (literally) enchanted her, the word used being “glamer/glamour/glamourie/-ye”, a Scots and perhaps even then archaic word for magic/magic spell. Except for variant G, which, instead of the Gypsies casting their glamour/glamourie over her, has: “They called their grandmother over.”

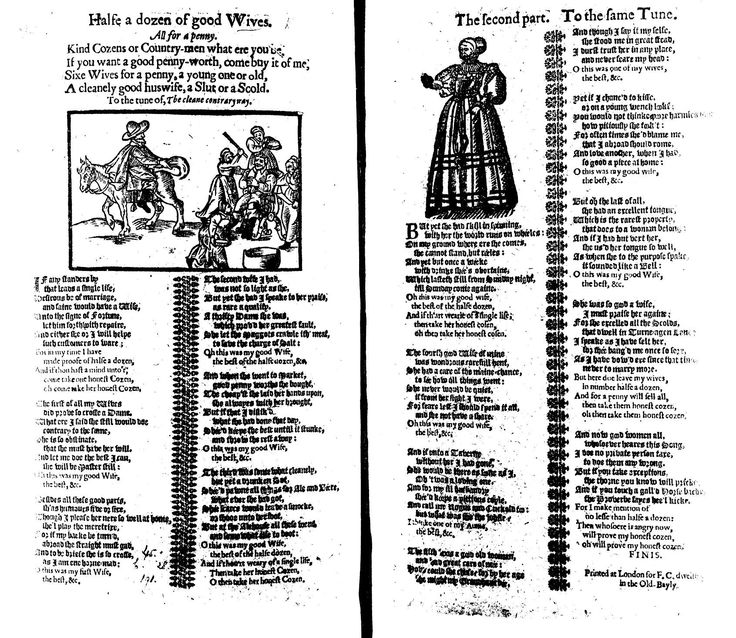

In an introductory note, Child writes that he collected it from the Roxburghe Ballads, a selection first published in 1847 (for more on this and its somewhat dubious history, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roxburghe_Ballads and for more on the original collection, see: https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/page/roxburghe ), and which is derived from a mass of popular sheet music of the 17th and 18th centuries.

I suppose one could say that “grandmother” simply shows that the word “glamour/glamourie”, from Scots, was simply misunderstood by whoever was behind variant G, but, remembering “My country dizzily”, I would suggest that it’s just as likely that someone misheard the word—and a new character was added to the ballad. (For the ballad and its variants in Child’s edition, see: https://archive.org/details/englishandscopt104chiluoft/page/60/mode/2up )

And this is certainly true for another ballad example, in which another character sprang suddenly into being. This is from Child #181, “The Bonnie Earl of Moray” in which the narrator sings:

“Ye Highlands and ye Lawlands,

Oh where have you been?

They have slain the Earl o’ Moray

And layd him on the green.”

and from which came that character—Lady Mon de Green (also written Lady Mondegreen). And what’s interesting here for me is that this has become a general term for a misheard lyric, a “mondegreen”, but invented not by a linguist, but by a humorist, Sylvia Wright (1917-1981), and published in an article in Harper’s Magazine in 1954. (See: “The death of Lady Mondegreen” in November’s issue) Wright explained that she, as a child, had—you guessed it—misheard that line in “The Bonnie Earl of Moray”—so you can see that childhood (mine, Wright’s) and orality can have the same effect. (For much more—and I mean much– on the subject, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mondegreen )

But one more example—fitting for the season and what we might call a mondegreen with intent—in fact an entire song:

“Deck us all with Boston Charlie,

Walla Walla, Wash., an’ Kalamazoo!

Nora’s freezin’ on the trolley,

Swaller dollar cauliflower alley-garoo!

Don’t we know archaic barrel

Lullaby Lilla Boy, Louisville Lou?

Trolley Molly don’t love Harold,

Boola boola Pensacoola hullabaloo!

Bark us all bow-wows of folly,

Polly wolly cracker ‘n’ too-da-loo!

Donkey Bonny brays a carol,

Antelope Cantaloupe, ‘lope with you!

Hunky Dory’s pop is lolly,

Gaggin’ on the wagon, Willy, folly go through!

Chollie’s collie barks at Barrow,

Harum scarum five alarm bung-a-loo!

Dunk us all in bowls of barley,

Hinky dinky dink an’ polly voo!

Chilly Filly’s name is Chollie,

Chollie Filly’s jolly chilly view halloo!

Bark us all bow-wows of folly,

Double-bubble, toyland trouble! Woof, woof, woof!

Tizzy seas on melon collie!

Dibble-dabble, scribble-scrabble! Goof, goof, goof!”

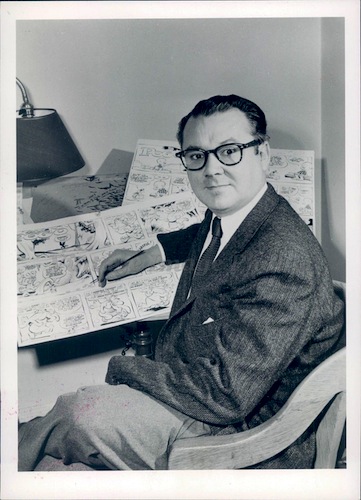

As this is a well-known Christmas carol, I won’t supply either the original, or a translation (and how would you translate “Chollie’s collie barks at Barrow”? or would you even want to?) It is the work of the cartoonist/satirist Walt Kelly (1913-1973)

Kelly was the creator of the comic strip “Pogo” and it’s the characters from there who bring us this willfully misheard wonder—

You can listen to it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SL0lPcNwRqQ and, with the lyrics above, join in.

As ever, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

Try to mishear something every day—it makes life…surprising,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

So, When Prince Charles succeeds his mother, Elizabeth II,

So, When Prince Charles succeeds his mother, Elizabeth II,