Tags

Andrew Lang, Basile, d'Urfey, de-caumont, fairy-tales, friederich-schulz, Gingerbread, Grimm Brothers, Munchkins, Pentamerone, Persinette, Petrosinella, rampion, Rapunzel, Rock Parsley, Romeo and Juliet, Seurat, Shahnameh, Tolkien

As always, dear readers, welcome.

I often pass by a very unusual house, one which I would find hard to describe—perhaps something the Munchkins might build,

combined with a gingerbread house,

in the spotty colors and patterns of a Seurat pointillismist painting.

(Seurat, “La Tour Eiffel” , 1889—if you like the look of this, see: https://www.georgesseurat.net/ for lots more—and, for more about this painting: https://artincontext.org/the-eiffel-tower-by-georges-seurat/ )

All of that might make you slam on the brakes and drive as slowly as possible past, but there’s an added detail—for the past year, there has been a ladder propped from the ground to a closed window on the second floor. It’s not anything exotic, just a plain aluminum extension ladder.

When I first spotted it, I probably thought: fixing a storm window or painting trim and didn’t think about it again.

But, after seeing it for a year, and remembering what the house looks like, I began to consider other possibilities—and I’m sure that, with that combination, you’re considering them, too.

Dismissing fire drills, it struck me that, as the house has a fairy tale look, it must have something to do with such stories,

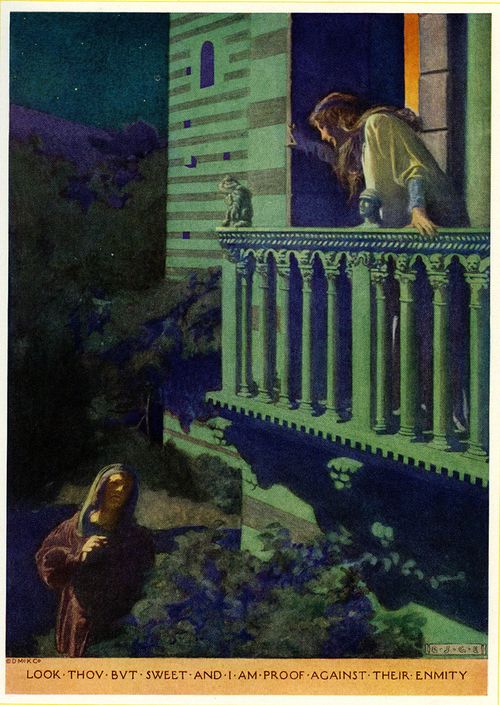

First, ir could be something Romeo and Julietesque—but, instead of standing under her balcony

and then scaling it,

Romeo stopped by the local hardware store and properly equipped himself. (They eloped, as planned, this time, without the tragic ending, where everyone’s been stabbed or poisoned.)

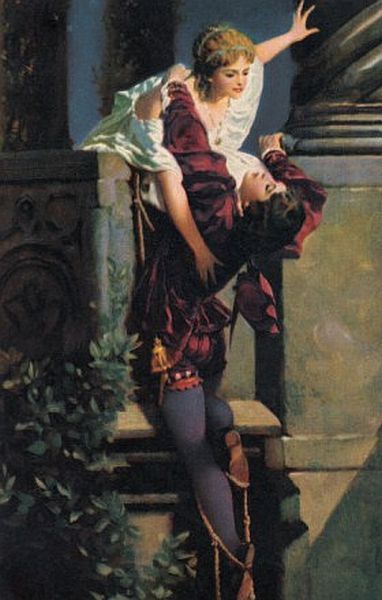

Or—not Romeo and Juliet, but Rapunzel and her (fill in name here—“Charming” being a common place-holder) Prince, who is, for a change, a little more considerate than the usual prince in the story..

After all, have you ever had your hair pulled? Granted, if you’ve got fifteen feet or more of it—but wait—let’s go back a bit.

(Although, in an interesting variant of this theme, from Ferdowsi’s 10th/11th-century epic poem “Shahnameh”, a prince, Zal, when offered a princess, Rudaba’s,, hair as a means of escalade, takes a lariat from a retainer, instead. See: https://archive.org/details/shahnama01firduoft/page/270/mode/2up )

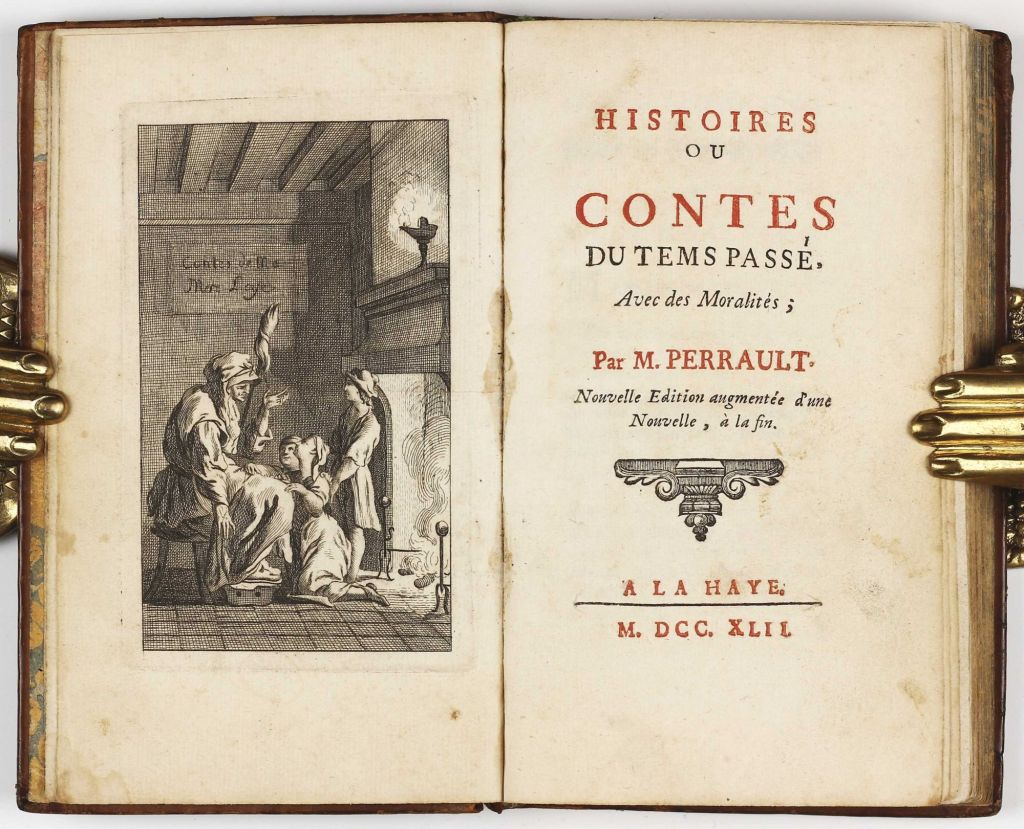

It all seems to begin with a late Renaissance story collection, Giambattista Basile’s (1583-1632 )

Pentamerone.

(so far the earliest printing I can find—as you can see, it’s dated 1749—but it gives away a secret: Giambattista Basile was actually Gian Alesio Abbattutis—although “abbattuto” in modern Italian means “depressed”—so was his work, like Thomas d’Urfey’s subtitle to his “Wit and Mirth”—“ or Pills to Purge Melancholy”, an eventual 6-volume collection of poems and songs, published between 1698 and 1720, an attempt to relieve despair? You can see all six of d’Urfey’s volumes here: https://archive.org/details/imslp-and-mirth-or-pills-to-purge-melancholy-durfey-thomas/PMLP144559-Vol._1/page/n5/mode/2up Don’t be confused by the spelling of the subtitle of the Basile, by the way: this is the southern Italian/Sicilian spelling of “conto”—“story”, so it means “the story of stories”, meaning “the very best of stories” .)

published posthumously by his sister, Adriana, in two volumes, in 1634 and 1636.

Its title means something like “Five Days” and the title comes from the framing story—which you can read about here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pentamerone In sum, ten story-tellers are hired each to tell one story a day for five days, making a total of fifty stories.

The first story on the second day is “Petrosinella”—“Parsley”, the title coming from the name of the main character. (The modern Italian word is “prezzemolo” so I’m assuming that this is dialectal/archaic or both. Pliny, in his Natural History, Book XX, Chapter 47, mentions “petroselinon”—the Latin form being “petroselinum”—“rock (petra) parsley”, so I’m guessing that “Petrosinella” is what is called a metathetic form, where part of the word has been transposed with another, like “calvary” for “cavalry”. Maybe also confused with the Italian diminutive ending “-ella”, as if the meaning is “Little Parsley”. If you’d like to read what Pliny has to say about it—including being useful for snake bite, see: https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D20%3Achapter%3D47 )

A brief summary of the plot:

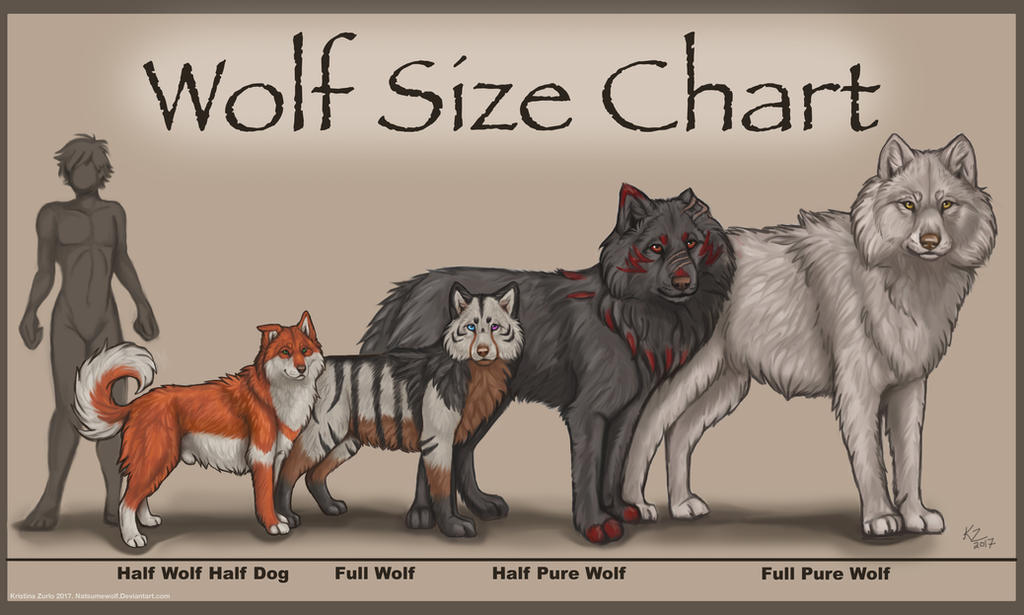

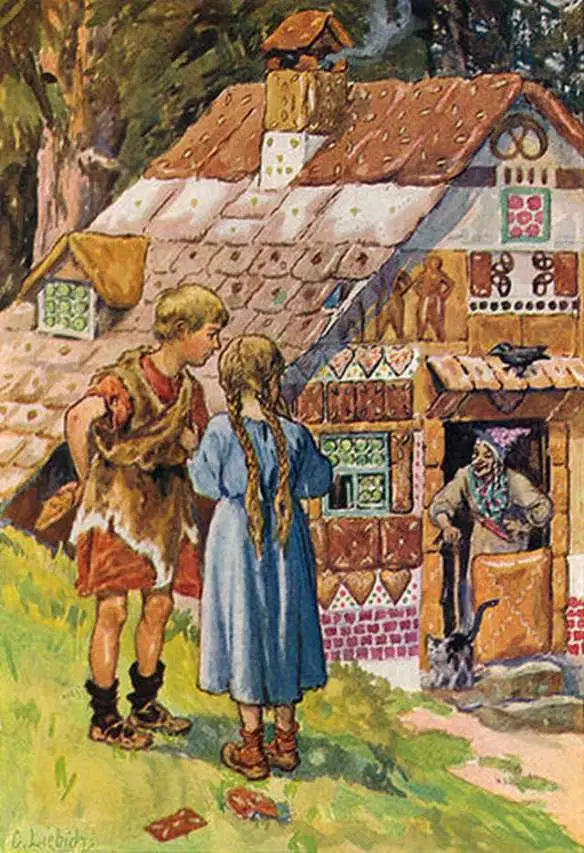

A pregnant woman repeatedly visits the garden of an orca (ogress—now, however, a killer whale—not what Basile had in mind, I’m sure)) to steal parsley, The ogress catches her, but lets her go on condition that the ogress gets the child. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? Eventually, she gets the child, whom she puts into a tower with only one high window and visits her by using the girl’s hair.

And, if you know “Rapunzel”, you know what happens next—prince, etc—but then the story becomes quite different, with Petrosinella and the prince escaping and the ogress eventually being killed. (Here’s the whole story for you in J.E. Taylor’s 1847 translation in a 1911 illustrated reprinting: https://archive.org/details/31383047427094/page/82/mode/2up )

Well, until the later part of the story, this looks more or less familiar, but, if this is the Rapunzel story, why is the main character called “Parsley”?

For that, we need to move to its next incarnation, “Persinette”, by Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de la Force, who published her version of the story, which she claimed was original, in a volume the title of which suggests that she had, in fact, read Basile: Les Contes des Contes (1698), making a slight change by pluralizing that first story in Basile’s subtitle, not to mention the fact that her heroine is named “Little Parsley” (“Persinette”—although one might expect “Persilette”, as the French word for parsley is “persil”).

A major difference between this and Basile’s text is that de Caumont’s is much more elaborate—including the detail that parsley was not available at that time and that the Fairy (no longer an ogress) has had to have it imported from India! Much of the basic story we read in Basile is there—the hair, the tower, but more has been added, beginning with it being Persinette’s father-to-be who steals the parsley, rather than her mother, the fact that the Fairy causes the tower to appear by magic, that, finding Persinette to be pregnant, the Fairy isolates her in a cottage by the sea, that Persinette has twins there, that the Fairy tricks the prince, who leaps from the tower and is blinded—so much more of which fits in with the familiar Rapunzel story. (Here’s a summary: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persinette but, for the complete story, so far I’ve only managed to find a 1785 French version, which, if you have some French—with 18th-century spelling conventions—you can read here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persinette )

But, although there are lots more familiar details here, we’re still in the land of parsley—how did we move to “rapunzel”—which isn’t parsley, but something called “rampion”?

This is an edible plant, once commonly grown and eaten, but now seems to have lost its popularity (for more, see here: https://botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/r/rampio03.html And a more scientific description here: https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=278824 )

The answer to the question of name change is: we move from Italian to French to German, as rampion replaces parsley in Friedrich Schulz’ 1790 collection Kleine Romane, “Little Novels”, in which he included his translation of de Caumont (available here in a transcription from the Fraktur (old German script) of the original: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/ssd?id=chi.81388905;page=ssd;view=plaintext;seq=281;num=271#seq281 and pages beyond–I’ve done a quick survey of the text, which sticks pretty closely to the French—except for that “rapunzel”, which is noted to be a rare plant, just as the parsley is in de Caumont, although the Fairy doesn’t get it from India.)

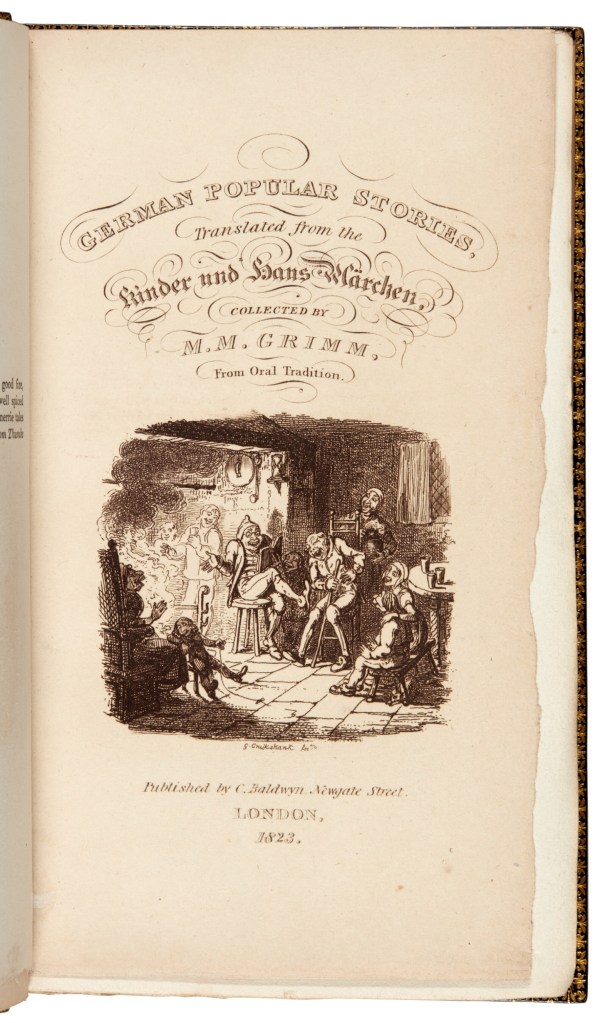

This, in turn, was used by the Grimm brothers in the first edition of Kinder und Hausmaerchen (something like “Children’s and Domestic Wonder-tales”) in 1812.

But one more but—how does the story come into English?

The first “translation” of the Grimm brothers’ work is the two volumes by Edgar Taylor, published in 1823 and 1826.

This is, in fact, only a selection, and doesn’t include “Rapunzel”, possibly because of Rapunzel’s pregnancy out of wedlock. As far as I can currently determine, the first English translation to include the story is the Edward H. Wehnert Household Stories, 1853, in two volumes, “Rapunzel” being in the first, and you can read it here: https://archive.org/details/householdstorie01grimgoog/page/n6/mode/2up?view=theater

From there we can move to Margaret Hunt’s 1884 translation in 2 volumes (here: https://archive.org/details/grimmshouseholdt01grim/page/n3/mode/2up?view=theater for volume 1 and here: https://archive.org/details/grimmshouseholdt2grim/page/n7/mode/2up for volume 2. This translation is noted in particular as it includes the Grimms’ editiorial notes, the first edition to do so.)

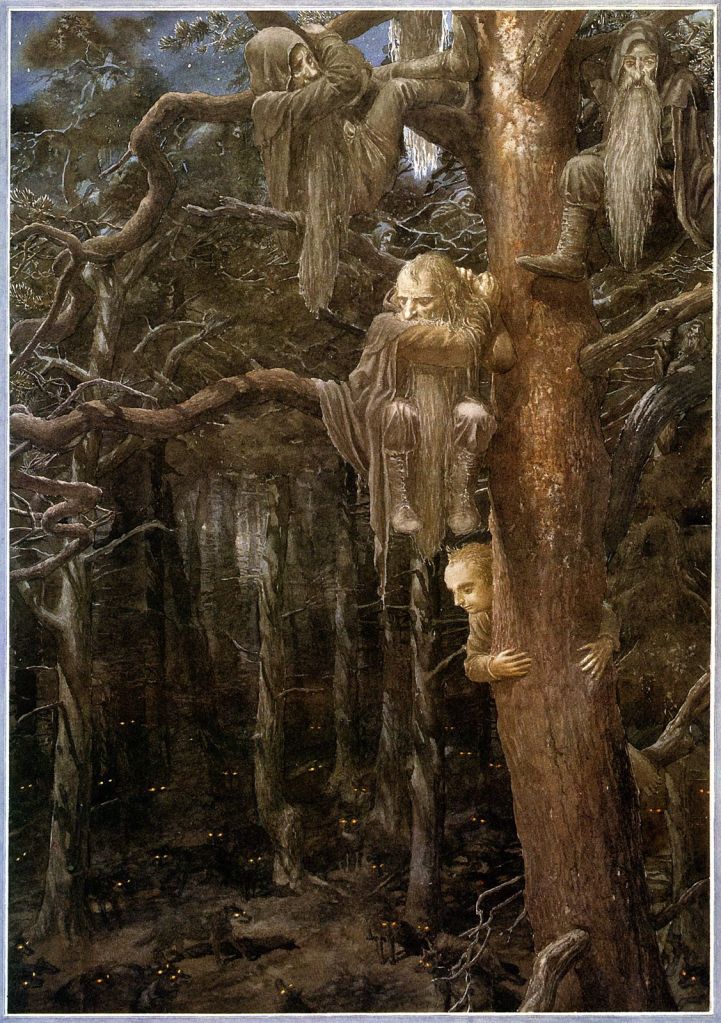

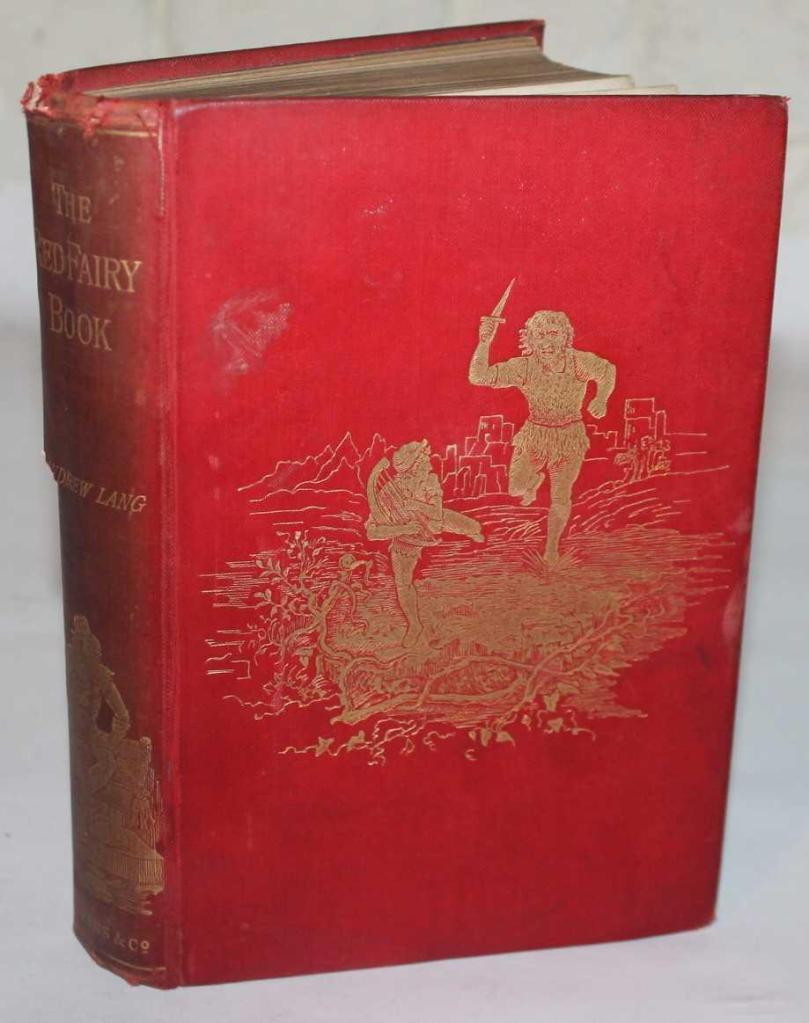

And, interesting–this edition had an introduction by Andrew Lang, who then included it in his 1890 The Red Fairy Book (https://www.gutenberg.org/files/540/540-h/540-h.htm ), where JRRT probably read it, as we know he knew other stories from the volume.

So, why is that ladder there? An updated fairy tale? Or just an absent-minded repairman? I’d prefer to think the former, although, in comparison with that long column of golden hair in the old stories

an aluminum extension ladder seems awfully drab.

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

If you’re acrophobic, best to seek adventure among dwarves,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

The change from “parsley” to “rampion”—and even which plant is “rampion”—has been the subject of scholarly discussion. See: https://writinginmargins.weebly.com/home/what-is-the-plant-in-rapunzel .Edward Taylor, in his 1846 collection, The Fairy Ring, even decided that either name was inappropriate for his British readers and changed her name to “Violet”! You can read his version here: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/ssd?id=uc1.31158001207546;page=ssd;view=plaintext;seq=367;num=321#seq367

PPS

If you would like to compare various English translations, from 1823 to 1927, see: https://archive.org/details/householdstorie01grimgoog/page/n6/mode/2up?view=theate