Tags

Anduin, Boromir, bridges, Etruscans, Horatius, Lars Porsena, Lays of Ancient Rome, Osgiliath, Tarquinius Superbus, The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

We’ve been traveling along the roads of Middle-earth in the last two postings, but we’ve taken a pause at Osgiliath,

(from the Encylopedia of Arda)

before our trip across the Anduin and beyond.

Frodo and Sam had crossed the Anduin by boat, much farther upstream,

(John Howe)

(Encyclopedia of Arda)

but the bridge here is broken—

and the real reason why it’s broken may lie, not in this Middle-earth, but in our own Middle-earth and far in the past, in the early history of Rome.

The earliest Italic settlers of the area had been farmers, who built communities on seven hills to the east of the Tiber River and farmed the land below.

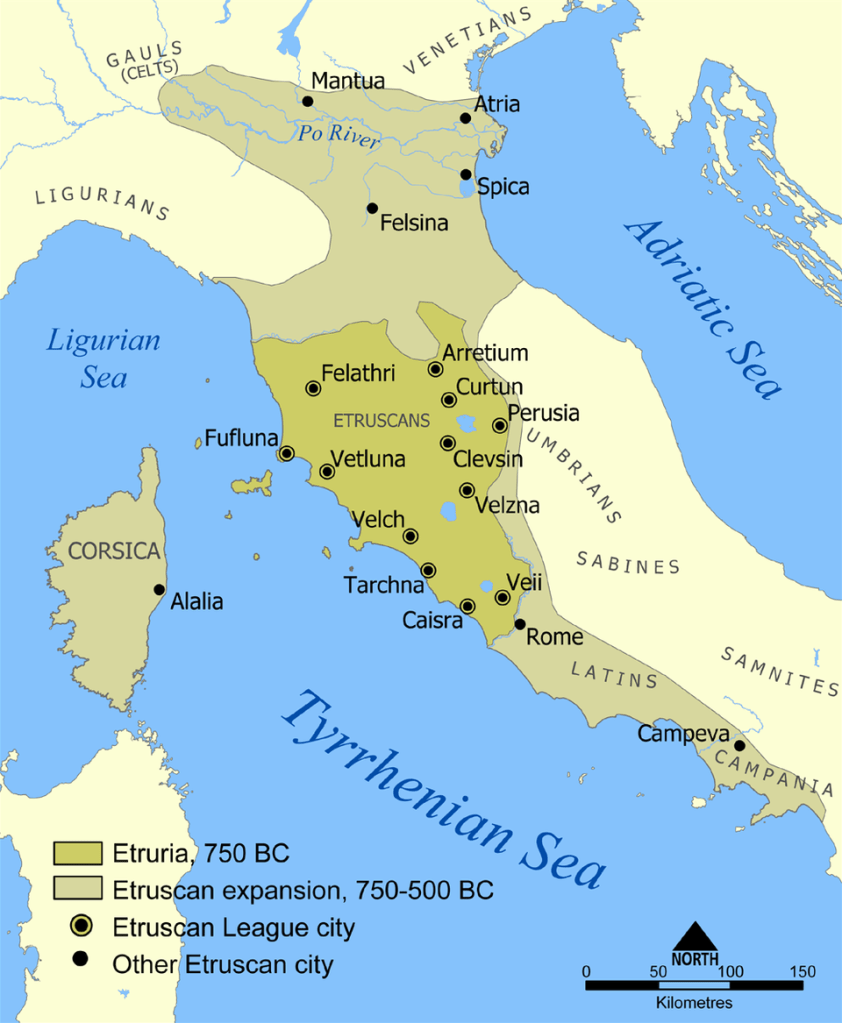

To their north was an older civilization, the Etruscans,

who were, culturally, a more sophisticated people.

They were also a more powerful military people

(Giuseppe Rava)

and eventually took over Rome for about a century (616-509BC).

Their last ruler of the city, Tarquinius Superbus (“Tarquinius the Arrogant”), was ejected, however, in 509BC, but did not leave quietly, going to the Etruscan king, Lars Porsena, in another Etruscan town, Clusium (Etruscan “Clevsin”),

for help. Porsena marched on Rome—

(Peter Connolly)

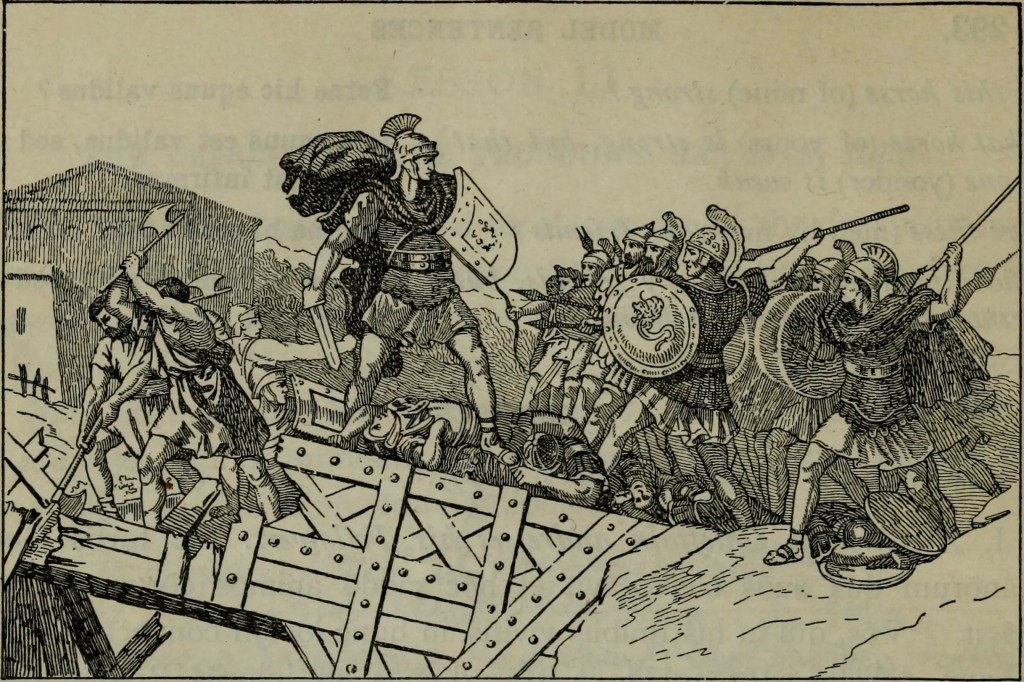

but, after this, ancient histories diverge—and so will we, as we pause once more at that bridge—the Pons Sublicius—the first bridge at the crossing of the Tiber. As Lars Porsena moved against the city, the Roman militia came out to fight and were defeated.

Their only chance to save Rome, they believed, was to break down the bridge and three Romans, led by a lower-rank officer, Horatius, held back the Etruscans with two higher-rank officers while that was done.

Under Etruscan pressure, the other two began to retreat, but Horatius stood his ground, even though wounded more than once, until he had word that the bridge had been broken. Upon that news, he turned, leaped into the Tiber, and swam to the other bank.

(Richard Hook)

At least one of our sources, Titus Livius (59BC-17AD), is doubtful about all of this, especially because Horatius was said to have done his swimming in full armor, but it fits into a regular story-pattern for Romans, in which a Roman suffers bravely—all for the sake of Rome. A favorite in this pattern was the story of Regulus, a Roman official, who, being allowed by his Carthaginian captors to return to Rome to deal with terms for a prisoner exchange, spoke against it in Rome, then returned to his captors to meet an unpleasant end. (For more on Regulus see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marcus_Atilius_Regulus_(consul_267_BC) )

Long after Rome’s empire was history—and legends—Horatius’ story survived and, in Victorian England, had become a literary staple because of the poem “Horatius ”, the first chapter in Thomas Babington Macaulay’s (1800-1859)

Lays of Ancient Rome (1842).

This also became a schoolboy staple, a popular favorite for memorizing and reciting in a world and time in which public poetic recitation was common. (Winston Churchill claimed that he had once won a school prize for doing so. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horatius_Cocles You can have your own copy of the first edition of Macaulay to recite from here: https://archive.org/details/macaulaylaysofancientrome/page/n7/mode/2up )

As a Victorian schoolboy, Tolkien

would have had a double exposure to this story, then: first, in his copy of Livy’s history of Rome, Ab Urbe Condita, and then in Macaulay—which is why, rereading this passage, in which Boromir details Gondor’s rearguard action against Mordor, I saw what may have been the ultimate source for Tolkien’s bridge:

“ ‘Only a remnant of our eastern force came back, destroying the last bridge that still stood amid the ruins of Osgiliath.

I was in the company that held the bridge, until it was cast down behind us. Four only were saved by swimming: my brother and myself and two others.’ “ (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 2, “The Council of Elrond”)

Thanks, as ever, for reading. Next posting: the third and last part of the little series on Middle-earth roads, where we’ll leap over the Anduin and move east.

Stay well,

Building bridges is always better than breaking them–just ask a Roman,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O