As ever, dear readers, welcome.

This posting will appear the day before Halloween, so, we’ll get into the spirit of the holiday (yes, pun intended),

with a story you might not know.

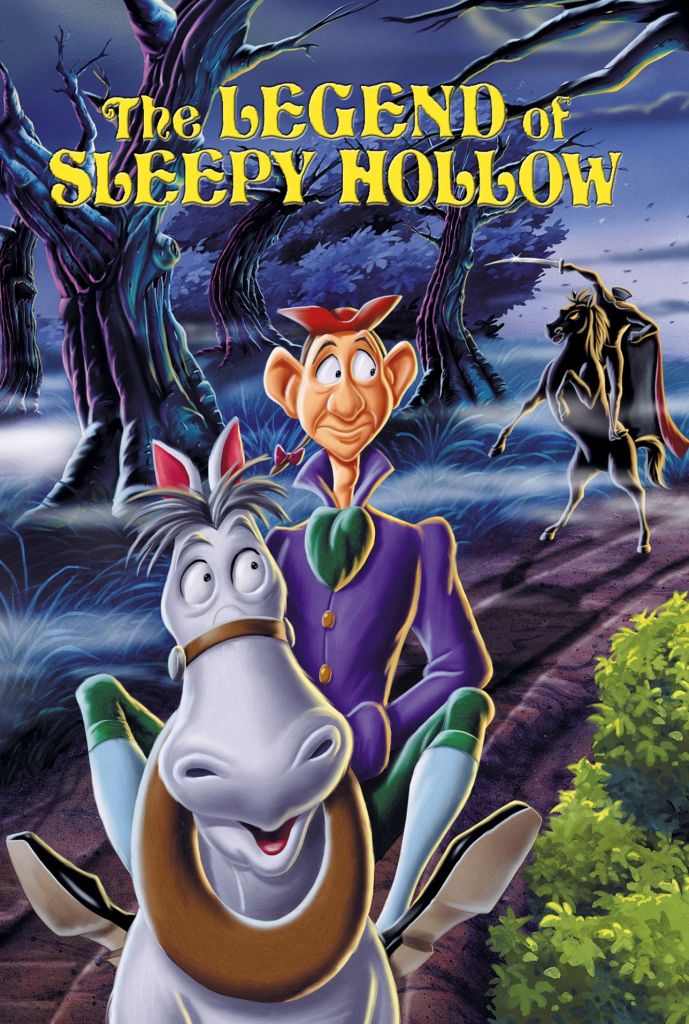

As a child, I most enjoyed and dreaded Halloween, the pleasure from thinking about what to dress up as—not to mention the candy—the dread because, yearly, there was the showing of this Disney animated feature—

In some ways, this was a Disney hybrid: the usual wonderful artwork (who could better create the sinister atmosphere of Ichabod Crane’s lonely ride through the increasingly spooky woods?)

but with a swinging, catchy score featuring the famous crooner (a kind of soulful singer from the 1940s—the animated feature dates from 1949), Bing Crosby, 1903-1977.

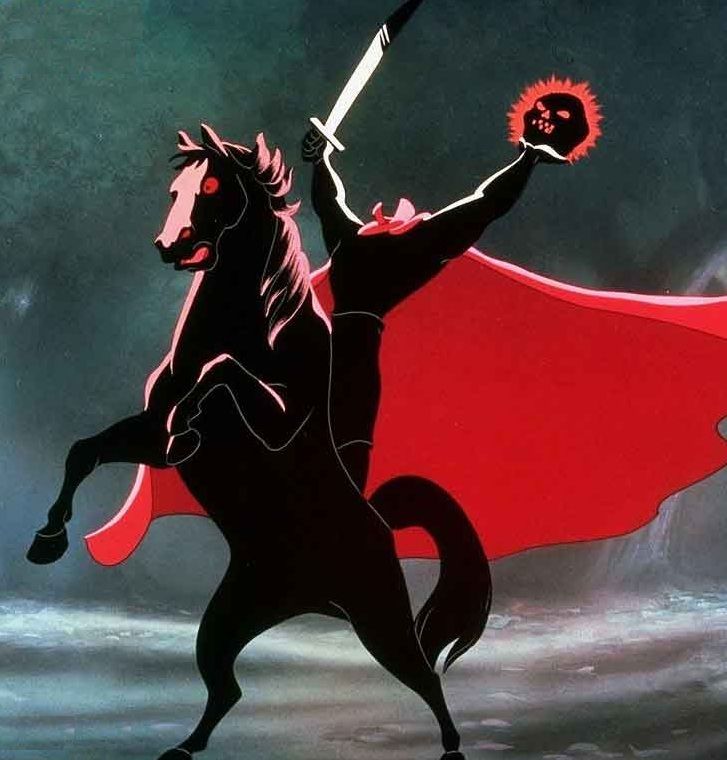

And the heart of the dread was the appearance of this character—

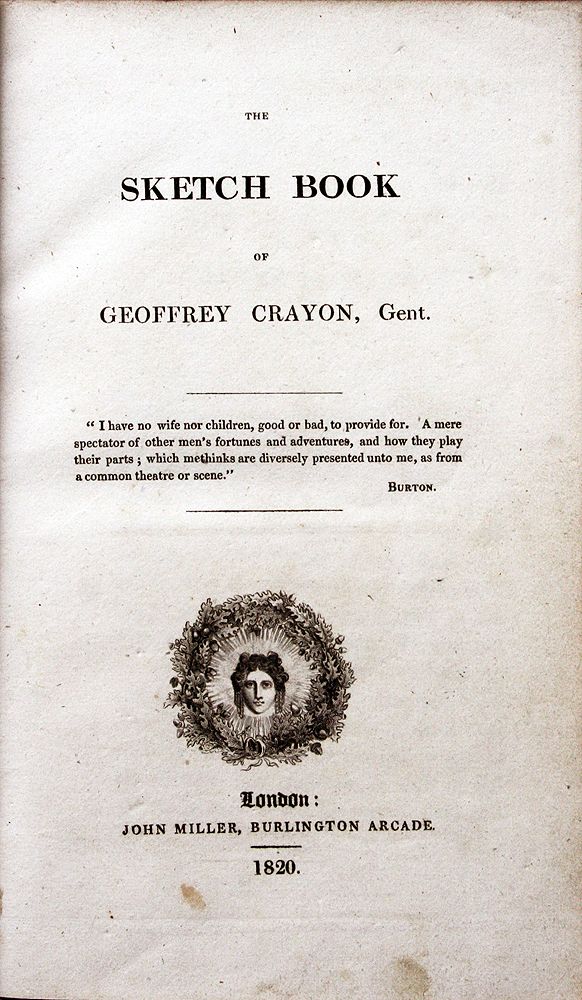

the Headless Horseman. (In case you don’t know the story, you can read it here, taken from Washington Irving’s, 1783-1859, The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., most of which being published serially in 1819-1820 and first time in book form in the US in 1824.

(one installment from the first British publication): This is from a 1907 edition of the two best-known tales from that collection of essays and short stories, “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, with illustrations by George H. Boughton: https://archive.org/details/ripvanwinkleandl00irvi/mode/2up For a complete edition (an illustrated version from 1864) see: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/2048/pg2048-images.html For more on the complicated publishing history of the work, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sketch_Book_of_Geoffrey_Crayon,_Gent. )

I’m not going to add a spoiler here, but the protagonist, Ichabod Crane, pursued by what he believes to be the headless ghost of a “Hessian soldier”,

eventually disappears, all discovered of him being:

“the tracks of horses’ hoofs deeply

dented in the road, and evidently at furious

speed, were traced to the bridge, beyond

which, on the bank of a broad part of the

brook, where the water lay deep and black,

was found the hat of the unfortunate Ichabod,

and close beside it a shattered pumpkin.”

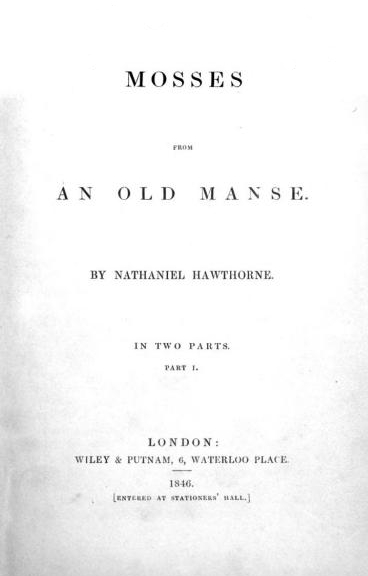

And this pumpkin brings us to another story, this one by Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1804-1864,

from his collection of short stories, Mosses from an Old Manse, first published in 1846.

This is “Feathertop”, originally published independently in 1852, and added to the collection for the second edition of 1854.

Hawthorne came from a very old Massachusetts Bay family (an ancestor, John Hathorne, had been involved in the opening stages of the Salem witchcraft trials in 1692) and the history of the Bay haunted him, producing short stories like “Young Goodman Brown” (1835), and the novels The Scarlet Letter (1850) and my particular favorite The House of the Seven Gables (1851).

“Feathertop” involves Mother Rigby, a pipe-smoking old witch,

(a relatively young witch, by Gabriel Metsu, 1629-1667, but, as you’ll see, the pipe is crucial)

who builds a scarecrow for her garden,

(by Carl Gustav Carus, 1789-1869)

including

“The most important item of all, probably, although it made so little show, was a certain broomstick, on which Mother Rigby had taken many an airy gallop at midnight, and which now served the scarecrow by way of a spinal column, or, as the unlearned phrase it, a backbone. One of its arms was a disabled flail which used to be wielded by Goodman Rigby, before his spouse worried him out of this troublesome world; the other, if I mistake not, was composed of the pudding stick and a broken rung of a chair, tied loosely together at the elbow. As for its legs, the right was a hoe handle, and the left an undistinguished and miscellaneous stick from the woodpile. Its lungs, stomach, and other affairs of that kind were nothing better than a meal bag stuffed with straw.”

Having constructed the body, she added

“…its head; and this was admirably supplied by a somewhat withered and shrivelled pumpkin, in which Mother Rigby cut two holes for the eyes and a slit for the mouth, leaving a bluish-colored knob in the middle to pass for a nose. It was really quite a respectable face.”

She dresses it in the remains of what were once fine clothes, including a rooster tail for his hat (hence his name), but, continuing to look at it, she says to herself:

” ‘That puppet yonder,’ thought Mother Rigby, still with her eyes fixed on the scarecrow, ‘is too good a piece of work to stand all summer in a corn-patch, frightening away the crows and blackbirds. He’s capable of better things. Why, I’ve danced with a worse one, when partners happened to be scarce, at our witch meetings in the forest! What if I should let him take his chance among the other men of straw and empty fellows who go bustling about the world?’ “

As you can see, this is quickly turning from a story of enchantment into a satire, as she animates the “puppet” (a word used in the 17th century to have, for witches, the meaning of something like a voodoo doll and used for the same purpose)

by getting it to puff on her pipe

before sending it out in the world to prey upon an enemy, Master Gookin, a wealthy merchant with a pretty daughter Mother Rigby wants him to woo.

Needless to say, in his enchanted form, and puffing on the magic pipe (he claims it’s for medicinal purposes), the scarecrow gains entry to Gookin’s house and even begins to romance the merchant’s daughter when, by chance,

“…”she cast a glance towards the full-length looking-glass in front of which they happened to be standing. It was one of the truest plates in the world and incapable of flattery. No sooner did the images therein reflected meet Polly’s eye than she shrieked, shrank from the stranger’s side, gazed at him for a moment in the wildest dismay, and sank insensible upon the floor. Feathertop likewise had looked towards the mirror, and there beheld, not the glittering mockery of his outside show, but a picture of the sordid patchwork of his real composition stripped of all witchcraft.”

The scarecrow, being reminded of what he really is, rushes back to his maker, smashes the pipe, and collapses into his component parts, leaving his creator to say to herself:

” ‘Poor Feathertop!’ she continued. ‘I could easily give him another chance and send him forth again tomorrow. But no; his feelings are too tender, his sensibilities too deep. He seems to have too much heart to bustle for his own advantage in such an empty and heartless world. Well! well! I’ll make a scarecrow of him after all. ‘Tis an innocent and useful vocation, and will suit my darling well; and, if each of his human brethren had as fit a one, ‘t would be the better for mankind; and as for this pipe of tobacco, I need it more than he.’ “

(You can read the story for yourself here: https://gutenberg.org/cache/epub/512/pg512-images.html )

And perhaps that scarecrow eventually found himself in a much more heroic role, much later in time and as far away as Kansas—

As always, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

Happy Halloween,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

Before pumpkins had come from the New World, the old world hollowed out turnips, like this one, putting a candle inside to light the dark world of the end of the old growing year.

PPS

In 1908, Percy MacKaye, 1875-1956, poet and playwright, dramatized a version of the story, which appeared briefly in New York in 1911, and you can read it here: https://ia902901.us.archive.org/23/items/scarecroworglass00mackuoft/scarecroworglass00mackuoft.pdf

PPPS

In 1961, there was a television musical of Hawthorne’s story,

with music by Mary Rogers, who then went on to compose the music for Once Upon a Mattress, my favorite version of Andersen’s “The Princess and the Pea” (which, looking at the Danish, which is “Princessen Pa Aerten” should really be “The Princess On the Pea”). You can hear a catchy duet between the witch and her scarecrow creation, “A Gentleman of Breeding” here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GXONisleuSw